Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

How to Write a Children's Picture Book in 8 Steps

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →It might be tempting to think that writing a children's picture book is easier than writing a full-length novel. However, a picture book actually requires all the same major storytelling elements that a novel does — such as well-drawn characters and an intriguing plot — just in a much smaller space.

The good news is that if you can achieve these things (with engaging illustrations to boot!), you’ll be poised to inspire the imaginations of young readers, who are always looking to welcome their next beloved picture book into their library.

To help all the aspiring authors who want to be the next Maurice Sendak or Margaret Wise Brown, we’ve put together this eight-step guide for how to write a children's picture book — plus tips for editing, illustrating, and publishing it!

Let’s start with the basics...

1. Come up with your idea

Successful picture books are the ones that strike the right balance between appealing to two different audiences: while a picture book is intended for children, it’s ultimately the parents who decide whether or not to buy it — or to read it aloud. (That being said, appealing to and entertaining adults shouldn’t take priority over the children you’re writing your children's picture book for.)

Luckily, coming up with an idea for your picture book is essentially the same as coming up with an idea for any book, for any age category. It’s how you present that idea that will differ. For instance, your picture book idea might center around specific childhood experiences, such as:

- Losing a favorite toy

- Bedtime struggles

- Imaginary friends

- Fear of the dark

But when you strip those ideas down to their core, you’ll find that their concepts are universal:

- Attachment

- Overcoming challenges

- Friendship

- Fear

In that respect, successful books don’t connect with readers because they present an idea that’s never been explored before. They succeed because they convey topics in new and interesting ways. Sure, Goodnight Moon has been helping parents put their children to bed for over 70 years. But you can be sure that stories about bedtime will continue to hit the shelves for a long time to come, provided that they look at the topic from different angles or act as an educational tool.

To ensure your idea is solid, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I presenting the theme of my book in a way that’s relevant to children?

- Do I explore the themes of my book in a way that feels unique?

- Will my book appeal to parents? This question can be trickier to answer, but if you can say “yes” to the first two questions, you’re probably on the right track here as well. Also, as an adult yourself, think about the picture books that have stuck with you, and then take note of the elements that keep the book fresh in your mind as an adult.

If you’re struggling to nail down the core concept of your book, this guide to story themes might help. Or perhaps it’s inspiration you’re after, in which case this list of the best 100 children’s books of all time is sure to get your creative wheels turning!

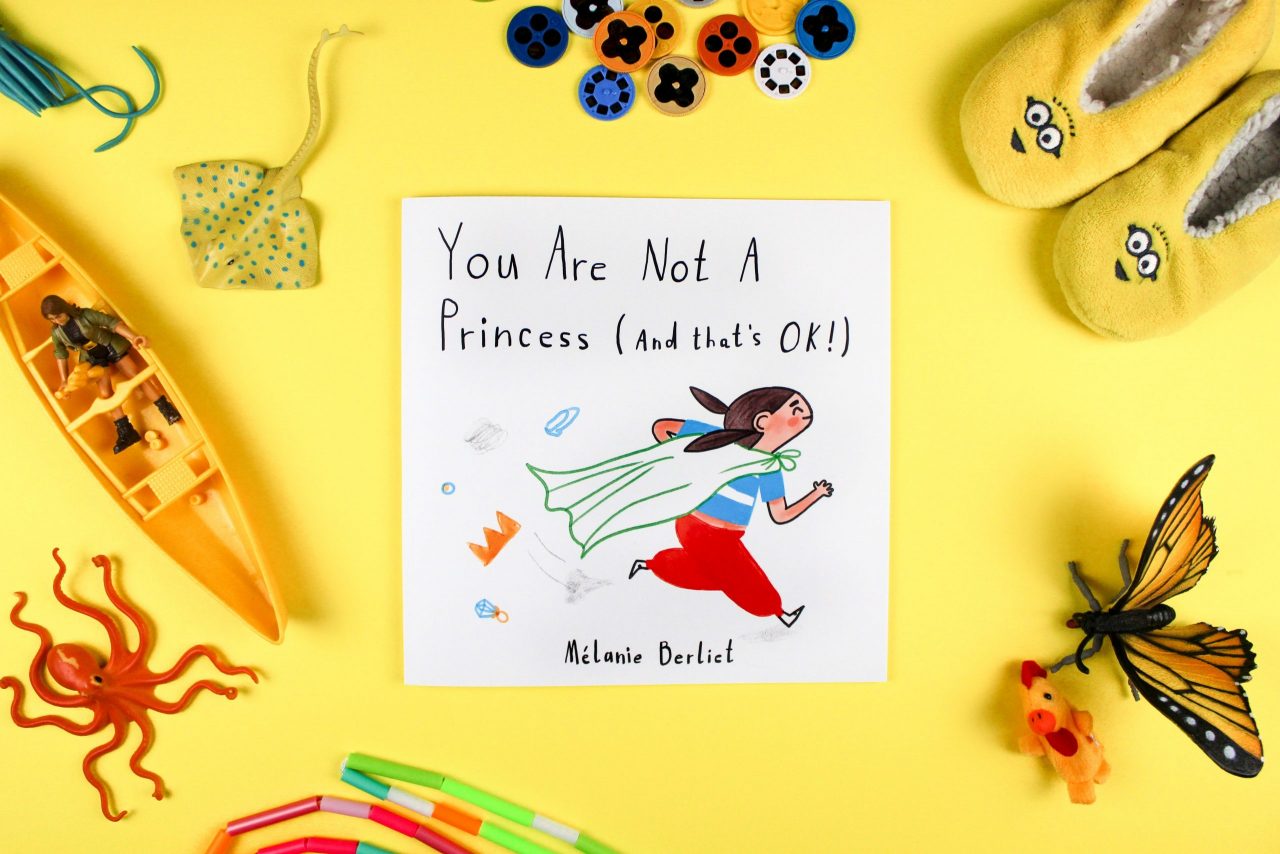

2. Identify your reading category

As mentioned before, the way you tell your story should depend on the intended reading age of your children's picture book. This includes everything from illustrations and marketing, to almost every other aspect of your book.

As mentioned before, the way you tell your story should depend on the intended reading age of your children's picture book. This includes everything from illustrations and marketing, to almost every other aspect of your book.

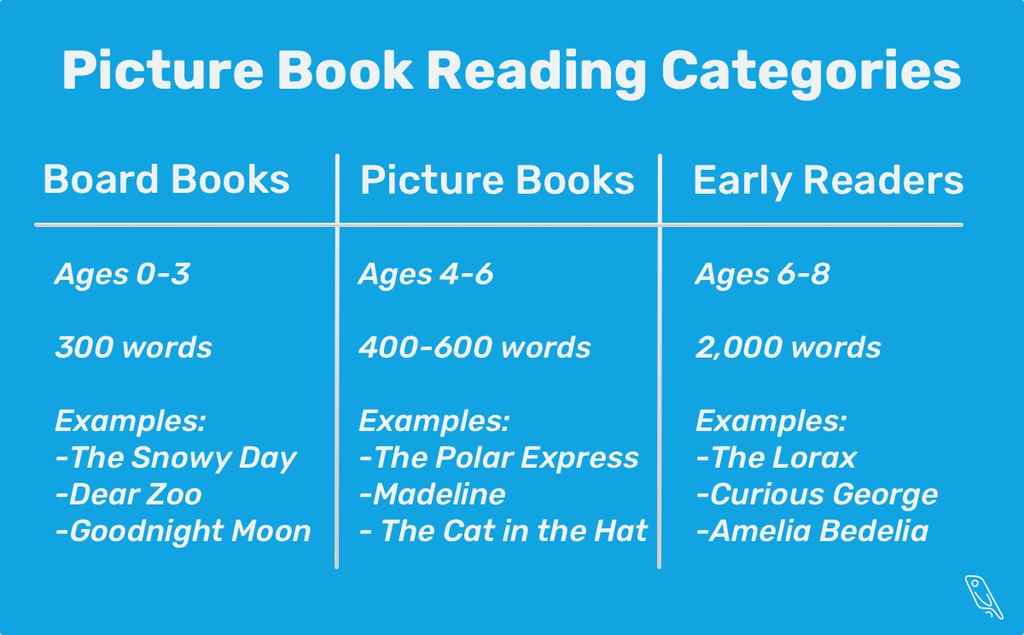

Let’s take a quick look at the different types of books that rely on illustrations, as well as some popular examples of each.

Board Books

- Reading age: 0-3 years

- Length: around 300 words

- Examples: Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin Jr., The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle, The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats

Picture Books

- Reading age: 4-6 years

- Length: 400-600 words

- Examples: Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg, Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans

Early Readers

- Reading age: 6-8 years

- Length: around 2,000 words

- Examples: Amelia Bedelia by Peggy Parish, The Lorax by Dr. Seuss, Curious George by H.A. and Margaret Rey

Chapter books — for readers between 9-11 years-old — also typically contain illustrations. However, they’re often black and white sketches as opposed to full-color illustrations, and the pictures are used to complement the story rather than to help tell the story. If you’re looking for more in-depth details on the reading ages of various kid lit, check out this guide to writing a children’s book or sign up for the course below!

FREE COURSE

Children’s Books 101

Learn the ABCs of children’s books, from audience to character and beyond.

3. Work out your narrative voice

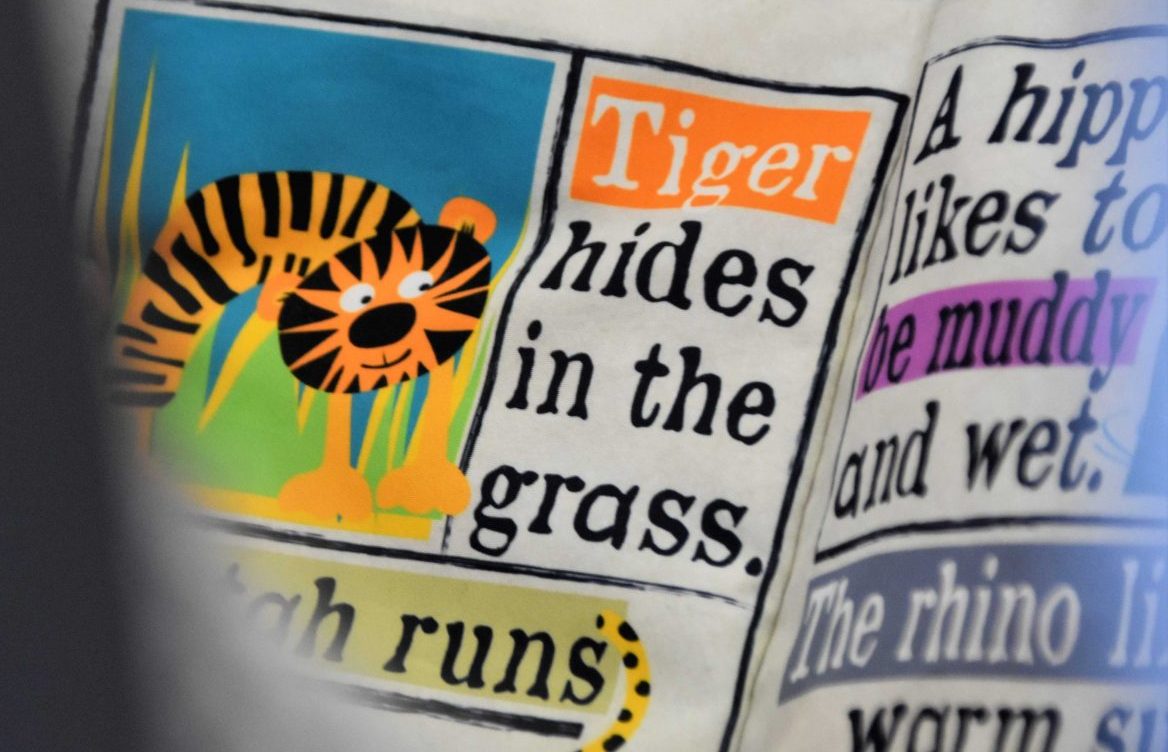

Even though many kids are able to read to themselves by the time they’ve graduated to the picture book and early reader categories, all books that rely heavily on illustrations are often still read aloud. That’s why rhyming in children’s books is pretty common — it creates a fun and engaging vocal storytelling experience. (Still, rhyming is not always a good idea for picture book writers — more on that below!)

Besides prose that sounds good out loud, there are a number of other factors to keep in mind regarding the narrative style of your picture book:

Vocabulary

If you’ve ever casually dropped a word into a conversation with a child, only for them to ask you what it means, and stump you as you try to find a way to explain it, you’ll know the importance of tailoring the vocabulary of your picture book to the age range of your readers.

This, again, means striking the right balance. You want the vocabulary you use to be accessible to children. At the same time, you also want to offer young readers the chance to expand their understanding of language — aided by the illustrations. As children's editor Jenny Bowman says, “Children are smarter than you think and context can be a beautiful teacher.”

If you’re unsure whether the vocabulary in your book hits the right note, your best bet is to read other picture books to compare, and to get feedback from parents and children themselves. (But more on that later.)

Repetition

On the note of helping young ones expand their vocabulary and reading skills: repetition plays a key role in many picture books!

The use of repetition allows children to anticipate what the next word or sentence of a story might be, encouraging them to participate in the act of reading and following along.

Examples include Bear Snores On by Karma Wilson, Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, and One Day in the Eucalyptus, Eucalyptus Tree by Daniel Bernstrom. Oh, and almost anything from Dr. Seuss, of course!

Rhyming

As with repetition, rhyming can help children anticipate upcoming elements in a story. It can also contribute to a more fun, memorable reading experience — how many of us can still rattle off “I do not like green eggs and ham, I do not like them Sam, I am!”

However, as all aspiring picture book authors know, it’s incredibly tough to get rhyming really right. An otherwise wonderful book can be brought down by sloppy rhyming, and unless you’re Dr. Seuss’ equally-talented grandchild, publishers will likely be wary of your rhyming manuscript. So deciding to go the rhyme-time route is taking a risk.

But if you decide that rhyming is the style for you and anything else simply won’t do (see what we did there?), remember that the story should always come first. Don’t sacrifice plot or any other important story elements for the sake of your rhymes.

Point of View

Point of view refers to the perspective of the narrator. If a story is told from…

- First person, the narrator is the person the story is happening to and will use words like “me” or “I.” For example, Love You Forever by Robert Munsch.

- Second person, the narrator is placing the reader within the story and will use words like “you” or “your.” For example, In New York by Marc Brown.

- Third person, the narrator is telling the story from outside the action. In third person limited, the narrator is only able to reveal the thoughts and feelings of one particular character, while in third person omniscient, the narrator knows the thoughts and feelings of all characters. This POV uses words like “he” or “she.” For example, Corduroy by Don Freeman.

Deciding what POV you want to use is a big decision when it comes to how to write a children's picture book, and all of them have their own strong suits, depending on the story you’re telling. Love You Forever, for instance, is a book about unconditional love and is a comforting read (of course, until you’re older and suddenly it becomes a real tear-jerker!), so it makes sense that the narrator is speaking directly to the reader, using second person language like “you.”

🖊️

Which famous children's author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes 30 seconds!

Learn more about each narrative perspective in this guide to point of view.

4. Develop engaging characters

Writing a picture book is not an opportunity to scale back the work that goes into creating realistic, well-rounded characters with their own motivations, struggles, strengths, and weaknesses. Yes, you’re telling a story with far fewer words than a novel, and you have the benefit of using illustrations to help convey meaning, but your characters should still feel like real people.

Think back to the books you enjoyed as a kid. Likely, they stand out to you because you loved or related to their characters. If a parent or guardian knows their child has become a fan of a specific character, they’re also far more likely to continue buying more picture books about that same character. So taking the time to write fully-realized characters will not only allow you to hone your craft, but it’ll also allow you to build a fanbase.

Keep in mind that characters don’t need to mirror kids to appeal to them. You don’t need to worry about alienating your customer base by writing characters that don’t look, sound, or act as they do. Indeed, striving to create a cast with as broad appeal as possible is a ticket to creating forgettable characters. Don’t be afraid of cooking up unique characters that will connect with children in their own special ways — think about how many kids hold animals, aliens, or anthropomorphized objects near and dear to their hearts.

To help you out on that front, we’ve got three handy resources:

- A free downloadable template to help you build your character from the ground-up.

- A guide to building up your characters and really zero in on what makes them tick.

- This list of character development exercises that you can turn to any time you feel a sense of disconnect with your characters.

Don’t forget to consider the significance of providing children with access to characters that represent them. Read up about the importance of diversity in children’s books here.

5. Show, don’t tell

A piece of advice extended to all authors, “show, don’t tell” actually puts picture book writers at an advantage because of the illustrations that accompany their books! And you should absolutely rely on your illustrations to convey things to readers, allowing you to save your limited word count for other things.

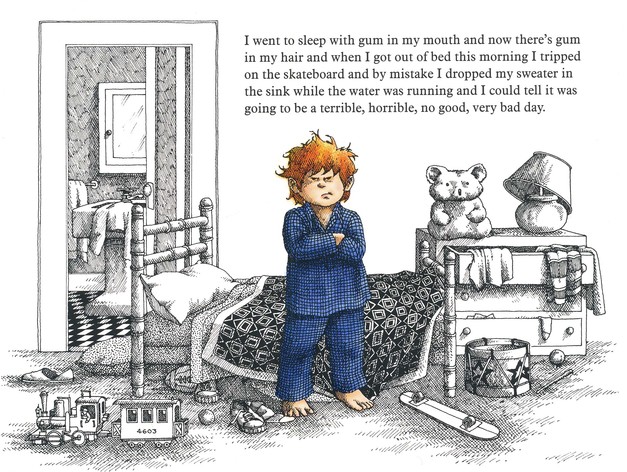

Of course, the concept of “showing” by employing sensory details in your writing still applies to children's picture books, too. For instance, in Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, author Judith Viorst doesn’t need to repeatedly remind readers about how annoyed Alexander becomes throughout the day. He does so by focusing on the frustrating events Alexander encounters, and by using the illustrations to elaborate on how Alex is feeling. Consider his disgruntled expression and tersely folded arms in the image above.

One tip for making sure your picture book shows instead of tells is to look for instances of the words “is,” “are,” “was,” or “were.” Double-check if any of the sentences associated with these words are telling the reader something you might be able to show them instead.

Brush up on this golden rule of writing with this comprehensive guide to “show, don’t tell.”

6. Edit and seek feedback

As we just mentioned, every word really needs to count in a book with so few words. So the first step of your editing process should be to go through your book line by line, and for each one consider: is this line crucial for my story? If the answer is yes, carry on. If it’s no, remove it!

After you’ve finished that, go back through your manuscript looking for any spelling or grammatical errors.

Once you’ve gotten your manuscript as polished as you can, it’s time to seek out feedback from the most honest beta readers out there: children!

If you have friends or family with children, ask them to read your book to their little ones, taking note of their feedback. Bonus points if you can watch someone reading your book to a child, as you’ll not only get their reaction, but you’ll also get a chance to hear what your book sounds like read aloud by another person.

There are also a number of great communities for children’s book authors out there that you can join for critiques and feedback.

Finally, if you want to be really sure that your picture book is ready to capture the imaginations of young readers, consider working with a professional editor. Editors pull from their insight into the publishing market they specialize in to inform their feedback — so the benefits an experienced children’s book editor can provide your story are significant.

If you want to dip your toes into the idea of working with a professional editor, you can sign up for a free Reedsy marketplace account and request quotes from a number of different children’s editors at no cost — including some who have worked with popular authors like R.L. Stine and Daisy Meadows!

Hire an expert

Sarah K.

Available to hire

I'm a British Asian Cambridge-educated editor and author with over 20 years experience in publishing.

Taylor M.

Available to hire

Over twenty years of experience as both a writer and editor specializing in middle grade and young adult literature.

Margaret M.

Available to hire

Developmental Editor specializing in Y/A and middle grade, formerly at Penguin and Simon and Schuster

At this point your children's picture book should be complete! You can now turn your sights to illustration and publishing.

7. Illustrate your picture book

If you’re hoping to have your book traditionally published, you can skip this step and go straight to the next. In just about every case, if your book is acquired by a publisher, they will want to choose their own artist to take care of the illustrations. In fact, sending a publisher your already-illustrated manuscript could harm your chances of landing a book deal as it may prevent editors from seeing how your book fits them. Think of it as going to see a house you’re interested in buying. If the place is covered with the current owner’s personality, you might have a tougher time seeing yourself living there. If the house is presented as more of a clean slate, you might walk in and spot the potential right off the bat.

Now, if you’re planning to self-publish your children's picture book, you will absolutely want to hire a professional artist to do the illustrations — unless you happen to be Eric Carle and possess both excellent writing and illustrating chops. Here's how to find the right illustrator for you.

1. Get an idea of the kind of illustrations you like.

Ultimately, the illustrator you hire will have input regarding what sorts of illustrations tend to work with the kind of book you’ve written. That being said, you should absolutely go into the process of finding the right collaborator with an idea of what you like. Head to your local bookstore and spend time browsing through the picture books there. Make notes of illustration elements you do or don’t like. Alternatively, scroll through these book illustration examples for illustration inspiration.

2. Establish a budget, brief, and deadline.

These are three key things you want to have in mind before you start looking for an illustrator. You want to know how much you can afford to spend on illustrations, how much work you need to be done (for instance, how many pages need illustrating and what type of illustrations you’re looking for), and what date you need the work completed by. This information will all play a big role in scouting out the designers that are right for your project. But remember, you may need to adjust your expectations as you start talking to illustrators and begin to get an idea of how much they typically charge and how long the average turnaround time is.

3. Thoroughly look through illustrator’s portfolios.

This is the best way to come up with a shortlist of illustrators you’re interested in working with. As well as getting a sense of their work and whether it’s up your alley, you should keep an eye out for their credentials: have they illustrated picture books for your age group before? Have they illustrated characters that resemble yours before? And so on and so forth.

4. Reach out to illustrators.

Once you’ve finalized your shortlist, start reaching out to illustrators by telling them about your book, and the budget, brief, and deadline details you worked out beforehand. If you’re looking for a secure environment to scope out experienced illustrators, sign up for a free Reedsy account to gain access to our vetted marketplace of professional illustrators. You’ll be able to check out their portfolios and past work experience with just the click of a button!

Hire an expert

Travis H.

Available to hire

Fantasy map illustrator. Clients include Penguin Random House and Sourcebooks.

Geoffrey M.

Available to hire

Nautilus Books Gold Award Winning Illustrator. Games, comics, books, graphic design, you name it, I've done it!

Judit T.

Available to hire

Currently cooking for US children's book publishers, mixing it with some storyboarding on the side and topping it with creative writing.

8. Publish your picture book

If you’re not yet sure which publishing path you want to take, here are a couple of things to keep in mind.

Self-publishing a picture book

If you want to dictate the amount of time it takes to bring your book to market, have the final say on all creative decisions, and keep a much larger percentage of royalties, then self-publishing your picture book is likely the right move for you.

That being said, self-publishing also means that you need to be willing to do all the marketing and distribution work yourself — and the costs associated with publishing your book will all have to come out of your own pocket.

For many authors, one of the biggest draws of self-publishing is accessibility. The picture book market is notoriously competitive when it comes to landing a publishing deal. It can be a very long game with an unclear outcome. So if your primary goal above all is to see your book published and available for little readers, stick to self-publishing.

Here some resources to help you along the way:

- How to Self-Publish a Children’s Book [blog post]

- Guide to Marketing a Children’s Book [free course]

- Guide to Print on Demand [blog post]

Traditionally Publishing a picture book

In a plot twist that everyone saw coming, the benefits to traditional publishing coincide with the potential pitfalls of self-publishing. Those benefits include wider distribution and greater chances of seeing your book stocked in brick-and-mortar stores, a production team who will work on the book at no cost to the author, an advance against sales, and at least a degree of book promotion — though even with traditional publishing, authors are expected to shoulder a portion of marketing efforts as well.

On the other hand, there’s the inaccessibility, slower publishing timeline, less creative input, and smaller percent of royalties that we also mentioned above.

If you’re set on traditional publishing, don’t forget to consider smaller indie publishers and small presses outside of the Big 5 publishers, who might be more likely to take a chance on an unknown children’s author.

Here are is some extra reading to answer more of your trad publishing questions:

- How to Publish a Children’s Book [blog post]

- How to Write a Query Letter [blog post]

- How to Identify The Target Market of Your Children’s Book [blog post]

Finally, whether you’re planning to self-publish your book or go the traditional route, this free online course is a great resource that breaks the process of publishing a picture book down into manageable steps.

Free course: How to publish your picture book

Get your picture book into the hands of little readers everywhere with this 10-day online course. Get started now.

And there you have it: how to write a children's picture book in eight steps. Whether you’ve landed on this blog post at the very start of your writing journey or in the middle of the publishing process, remember to keep the goal of reaching young readers in mind every step of the way. Bonus points if you can approach this often-challenging endeavor with a sense of childlike curiosity and fun 😊

Are you in the process of writing a picture book? Tell us about it — and ask any questions you might still have — in the comments below!