Blog •

Posted on Apr 28, 2023

Live Chat: How to Hone Your Editing Skills

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

View profile →Below is the transcript from our live chat on April 25th, 2023, where pro editors Jennifer Rees (The Hunger Games) and Fran Lebowitz (Bridgerton) discussed the tricks of the trade — from gaining the right kind of experience to honing your hard and soft skills.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Skip to 8:15 for the start of the talk.

Entering the world of publishing

Jennifer: My entry into the world of publishing was while I was completing my Master's degree in creative writing. I ended up working at an independent bookstore in Cincinnati for almost two years, which turned out to be a career defining job. It was the kind of bookstore where everybody “owned” their own section so that you had someone who was very knowledgeable about the books in each section.

When I joined, they had an opening in Children's. At first, I thought, “I have a master's degree, what do you mean?” but I was always a lifelong reader and lover of children's books, so I ended up really thriving there. I saw that there's a person behind all of these books and I wanted to try to be that person. So, when I moved to New York City, I interviewed with Scholastic for an entry-level job that I really wanted, as an editorial assistant.

I had no editing experience, but my boss at the time hired me based on my bookstore experience. I knew how to sell things, I knew what publishers were coming out with, and I knew the market. You know, someone could come in and say, “I need a book for my 11 year old son who loves sports” and I would be able to deliver that book to them. That's how I ended up in publishing, and at Scholastic for 15 years. I really loved it. I worked on amazing books and I learned so much.

It was a personal decision to become self-employed. I had had my third child and was going to sales conferences and doing a lot of things other than actually working on books. I found it pretty difficult to manage all of that, and I thought “I have enough experience, I'm gonna give it a go.” I've been freelancing now for almost 12 years.

FREE RESOURCE

The Full-Time Freelancer's Checklist

Get our guide to financial and logistical planning. Then, claim your independence.

Martin: That's interesting about bookstores. The editors I've spoken to here in the UK, where there's not as much of a culture around MFAs, all seem to have started off as a bookseller after university, and then moved on to an editorial assistant.

Fran, you started off at a different side of the publishing industry before you made your way into freelance editing, right?

Fran: Yes, I’ve worked both for small publishers where I got to do a lot, and for bigger places where my responsibilities were more limited. I started with a small publishing company called Acropolis Books, which is famous for Color Me Beautiful. There, I was marketing and writing book jackets and doing direct mail. Then I decided to try to go to New York City, and it wasn't very difficult to get an entry level job at the time.

I wanted to be in editorial, but it was $2,000 more a year to be in subsidiary rights. That taught me sales and contract negotiations, which set me up pretty well for going into an agency, going from a small agency, to a huge one, and then a boutique agency. And I think through the agency process, you start to learn the various arts of finding your taste, meeting the right people in the publishing world, and pitching — which helps with query letters — as well as formatting and polishing manuscripts for submission to publishers.

Martin: Yes, you mentioned that through your agency work, you picked up a lot of editorial skills. Do agents normally do a lot of editorial work?

Fran: I don't think it happens much anymore. I know that at Writer's House, for instance, they have a designated person who will read and edit the submissions. But I always wanted to do editorial work and enjoyed it, so I did. And I'm very glad because I said yes to some things that, with some extra help and some rolling up of the sleeves, turned into very good properties.

Chris Lynch, is one of them. He was on the slush pile and I worked on his first book for months and months. It started out as short stories and then we decided on how to make it into a cohesive novel which made him a National Book Award finalist and winner of many other awards. He’s written more than 60 books since.

Q: How did you gain experience in developmental editing?

Suggested answer

First, I honed my eye for assessing work as a reader for literary magazines, reading over 600 submissions across a few years of volunteering my time. But I became a capable developmental editor by rolling up my sleeves and providing feedback to my writing community. Eventually, that feedback-- for friends who write, for MFA classmates, for students who visited the university writers' center where I worked-- provided me with enough experience and practice to secure developmental editing work in the book world.

For better or worse, often someone in a specialized field (like editing) needs to prove their worth before they can make a living doing it. That applies to industries which rely on interns as well as apprenticeship models and more. I think developmental editing is similar-- hopefully your prospective editor (or work with) can point to specific books they've supported and share examples of their work.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Reading the slush pile

Martin: Jennifer, have you also worked the slush pile?

Jennifer: Oh yeah. That's one of your jobs when you're an editorial assistant. I would have stacks and stacks of submissions that I was reading through. Once in a while you would get something great and it was really exciting. Most were things that you would pass on, but it was actually a tremendous learning experience. You have to read some bad things to be able to recognize the good ones.

Martin: What were some of the wildest submissions you received?

Jennifer: I had a lot of glitter. People thought glitter was going to make you pay attention to their story and all it did was irritate me. I had people that would do artwork for me. I got gifts sometimes, chocolate, all kinds of things. But mostly you would just get the manuscript.

Fran: For me, sometimes my name was plugged in as the character. At times, I would get something huge where the first line of the query letter was, “I finally quit my job and am pursuing writing” and I just knew that it was going to be terrible. I think, on balance, whoever says that hasn’t written something worth quitting their job for.

JOIN OUR NETWORK

Supercharge your freelance career

Find projects, set your own rates, and get free resources for growing your business.

Basic skills every editor needs

Fran: For me, one thing an editor needs to master is judging something on its own terms so that you’re not imposing your own taste and intellect or wit. Obviously, you need to read in the genres you’re editing and, in this day and age where there is so much feedback everywhere, you need to understand who the client is so that you’re not going to devastate them, while also being able to be honest.

Jennifer: A big one for me, to touch on what Fran said, is to truly understand your client. My job is very different now than it was when I was at Scholastic. I have a lot of brand new people coming to me who are really nervous to send their manuscript. To that type of person, you want to buoy them up and help them write a better story. Part of doing that is to not give them feedback they can’t handle, but let them know what they’re doing right. I think that’s really important, and it’s taken me years to learn, because as an editor I’m always focused on what needs work. So to give constructive feedback in a way that is productive and makes them feel good about it is key.

💡 Some of the most valuable editor skills are judging a book on its own terms, truly understanding your client, and always providing constructive feedback they can handle.

I try to find out as much as I can about my client in terms of what this story means to them and what their intentions are. Because, as Fran was saying, I don't want to insert myself into their story. I want to help them fulfill their vision and create better stories so that they can walk away from our collaboration with something they're really proud of, whether or not it will be published.

I really feel like that connection is super important, especially because a lot of it is via email. So it’s about asking a lot of questions and making sure that, before you start their book, you understand where they're coming from.

Q: What, in your opinion, is the most important job of a developmental editor?

Suggested answer

A developmental editor should be able to provide a clarifying, 30,000-foot view of your work. They should also present you with actionable recommendations for navigating your eventual revision, and those suggestions should align with your aims for your work. In other words, the best developmental editors help assess and deftly improve your work on your terms.

Often, when a writer is ready to hire a developmental editor, they can no longer see the forest through the trees. They've named and renamed their protagonist twelve times, substituted commas for semicolons, and have usually read the manuscript more times than they'd like to admit. Hopefully, a good developmental editor will help you reset and see the draft with fresh eyes. They should be able to articulate the draft's aims, successes, and drawbacks in a way that's recalibrating for the author. And when it comes time to propose changes, that editor should be able to articulate the clearest, deftest path forward for the author.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Developmental editing differs over the different genres. Developmental editing for a novel is not the same as developmental editing for a poetry collection or a memoir, For instance, for a novel, developmental editing would include compiling notes on things such as coherence, characterization, plot lines, time lines, POV, writing style, and internal logic. For a poetry collection, it would be things such as poem flow, strength of individual poems, integration of the poems within the collection, etc.

However, there is one factor that remains the same throughout—and that is the task (nay the duty) of the editor to maintain the author's vision. Too often editors will mess with an author's "voice" under the guise of developmental editing. Developmental editing consists of improving the author's voice/vision while ensuring that, at the end of it all, it is still the author's voice/vision and not any imposed by the editor.

Michael is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Building a story is like building a house: First, you lay the foundation. You build walls and lay down pipes before you start thinking about painting walls and hanging wallpaper. Before we worry about the line level, we talk about the building blocks of a story.

It's normal to make big revisions after a developmental edit; in fact, it's almost always necessary. That's why it's helpful to do a dev edit after two or three drafts. You don't want to be too attached to anything at the line level before you've made sure your foundation is sound, just as you wouldn't hang wallpaper before you did the wiring.

In a developmental edit, we look at everything from characters' internal motivations to their plot arcs, from world building to conflict.

This is my favorite part of the writing process. When someone writes a story, they tell it to themselves. When they edit a story, they learn how to tell it to a reader. It's the step of the writing process that teaches us the most about how to be writers and how to communicate our visions to our readers.

Wendy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Traditional publishing vs self-publishing

Martin: Fran, would your approach to a client change depending on whether they have intentions to publish traditionally or whether they’re planning to go the indie route?

Fran: Yes, absolutely. As Jennifer said, if authors are self-publishing it’s more about what they're going to be proud of, instead of about going out in the world and potentially getting hammered.

If they’re sending their manuscript to agents, I tell them that they’re going to get hammered and then say “let’s try to mitigate that.” It's a different sieve so I'm much more blunt. We also discuss things like the publishing process and the current trends in New York City, like “own stories”. If you’re a man, for instance, how are you going to write for women?

If you’re self-publishing, I might still bring up things that are potentially problematic, but you don’t have to worry about that as much.

Fran: I'm still in touch with friends and my network. That's a secondary thing that I offer some clients. It’s not on the menu, but if somebody is really ready, I will help connect them with an agent or small publisher. So, I'm still in touch with people, I still do the reading, and I still try to listen to what’s going on.

Jennifer: Now that I'm not at Scholastic anymore and I'm not at board and acquisitions meetings, etc., I'm getting my information a little bit from the outside rather than from within like I used to, so certain industry publications, like Publishers Weekly and other children’s book writing organizations, are super important to me.

I still attend conferences, keep in touch with colleagues, and do work for some other people in the industry, so that's helpful too. And I ask lots of questions about what’s going on in the industry. That’s super important, otherwise I don't think I would be able to edit somebody who has the intention of approaching an agent. I want to be able to tell them, “We should really think about this a little bit differently, if that's the case.”

Giving feedback to authors

Martin: Do you find that you have to be very careful with how you communicate these points to authors, Jennifer?

Jennifer: I do. People are very attached to certain ideas in their story and there’s so much discussion right now about who can write what, so it's hard when you have someone who's written an entire novel and you have to tell them, “Nobody's going to look at it because it's not OK right now to have that kind of a story.” I'm super careful with that and I have a lot of conversations with them to see what their intentions are.

Fran: I usually play devil's advocate and say that the publishing industry that they're trying to break into is quite homogenous (and I do believe that even if there’s more diversity now than before, it’s still not representative of the wider population) so I advocate for self-publishing. And if it's something easy to identify and change that causes a problem in the content, I just ask them to change it. But, you know, usually I just make them feel a little bit better about not appealing to the gatekeepers and point to all the success stories of self-publishing.

Developing the hard skills of editing

Martin: Did you make any conscious moves to develop the hard skills of editing or is it something that just comes with experience?

Jennifer: For me, it's something that has definitely come with experience. When I was younger, I took a lot of courses and tried to learn as much as possible, but I found that my greatest teachers were the manuscripts that would pass across my desk.

I was super hungry when I first started and I would work on anything. I would go to people and say, “Hey, I know there's a story that sales is making you do that you don't want to do, so I'll do it.” I tried to get as much experience under my belt as possible, and I asked a ton of questions of people that I worked with.

Now I feel very comfortable and confident in my editorial skills, but early on, I just tried to learn as much as I possibly could from others who I worked with and also from classes, sources, editing guides, etc.

Martin: Fran, when you moved from your work in agencies to being a freelance editor, did you have to make any conscious steps to brush up on any skills?

Fran: I don't say no to as much. There are things that I would never touch before, but now I’m working on material that has some kind of comment or issue on every single page. We’re probably on the first edit of maybe 10 or more before it’s getting there.

Q: How do you adapt your editing approach to different genres and client expectations?

Suggested answer

Re. client expectations, before the work, practical goals need to be established.

I spend a lot of time with clients before offering bids, a lot of time. Call this free consultation if you wish, but since most of my clients don't know that they're about to step into the deep end of the pool, I think it's only fair that I warn them about the depth, as well as the shark infestation.

Dealing with different genres is a completely different issue.

Now, whether the book is humorous, horror, fantasy, adventure, sf, romantic comedy, or a mashup of two or more, I work with my clients to establish practical publishing goals (finding a publisher or self-publishing), and that sets the yardsticks for me to determine whether or not they measure up.

I'm personally comfortable with each of the genres I noted above, but if a client came to me with a genre-bending bodice-ripping romance, I'm probably not the right guy for the job.

Lee is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I work on picture books, novels, memoirs, and non-fiction, so I have a lot of different approaches in my pocket, ha. For picture books, it is much easier to do multiple rounds of edits, and most of my clients choose a multi-round package. That means I move from overall feedback down to line notes as the project progresses. I try to take a similar approach to longer projects, though I don't always get to see more than one draft. I'll often include taking a second look at a short excerpt--normally the beginning--in my editing package.

In term of client expectations, if I've done my job well, these will be clear before we even start working. I am constantly tweaking the language in my sales messages and offers to clarify issues that have come up with clients in the past. I am fairly flexible in changing my approach depending on how the client likes to work. For example, one client of mine prefers to talk through all of the changes in her picture book on the phone. That's pretty rare these days, but it works great for her, and we have a lot of fun on our phone calls!

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Each genre has an expectation from readers, so I edit according to the target audience and what they will expect based on the genre, title, and type of book, whether it is for children or adults, non-fiction or fiction.

Non-fiction readers of self-help, for instance, are looking to grow and learn. So I will edit this type of book for clarity, pacing, and whether or not it provides new information for readers that they are eager to learn. These types of books must also have strong takeaways and practical applications, since readers expect this from this genre.

A historical novel, a fantasy novel, or a sci-fi novel will need to allow for strong world-building. This is needed more so than in a novel that takes place in the present day.

So, having experience editing these types of books and keeping reader expectations in mind is what is needed here.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Common author errors

Fran: In my experience, it’s not so much that I’ve learnt any tricks, but you accumulate an idea of what is a common amateur error so you can quickly identify these things and explain them to somebody. Starting with overwriting, like “a dark and stormy night” or too much stage direction, not trusting your readership, and having a lot of gratuitous comments.

Another thing is being able to detect so easily how autobiographical a novel is because people cannot leave details that they cherish out, even though it’s gratuitous. It's not propelling the plot, it's not enhancing the character, it's not creating tension, and it's not emotional. It's not even lovely writing. It's just a detail that somebody can't let go of or doesn't have the distance to be able to judge properly. When it's frequent enough, they may think that they're fooling somebody, but you can just tell.

💡 Help authors let go of gratuitous autobiographical details that don’t build character, create tension, or propel the plot forward.

Martin: Jennifer what common mistakes do you see from a lot of your authors?

Jennifer: My authors tend to be writing for younger readers so I'll just talk about picture books specifically.

I see a lot of overwriting and not considering illustrated books as a visual art form. They’ll write, “There was a blue house with green shutters” and the descriptions will go on and on. I love helping people figure it out, but you have to say to them, “You need to think about your story visually, you will have all of that in your illustrations.”

Of course, you go through your rounds of editing to hone it and get them to think more visually. It's a fun process. But that's typically what I see with picture books: a lot of overwriting and people who want to write a picture book even though they never read them, which is the biggest no-no for me.

If that’s the case, encourage them to go to the library or a bookstore, and read, read, read. That's the best education you can possibly get as an author. So I do have a lot of people that just need to delve deeper. They have good intentions, but they need to know the art a little bit better.

Martin: Do you get authors who think picture books are an easy cash grab?

Jennifer: Yes. And I tend to not want to work with those people because they’re going to be difficult. If they think they’re going to write a New York Times bestseller, I pass on it. The expectations are just too high. And people do think it’s really easy, until they’re doing it and get really frustrated.

That's usually where I find myself having to be encouraging, but also point out where the story isn't working. And like Fran says, for some reason I get a ton of dog rescue stories and they're very attached to the way things actually happened. So I'm saying to them, “I know this is the way that this happened for you, but this is fiction. We can take some creative liberties to make it a story that is not just personal to you, but makes it universal so that other people will also find it interesting.”

🐣 For more insights into how to edit for early readers, check out this post by pro editor Kate Moening.

Practical steps to deliver better work

Martin: Fran, are there any small, practical steps or practices that you apply on a daily basis to help you deliver better work?

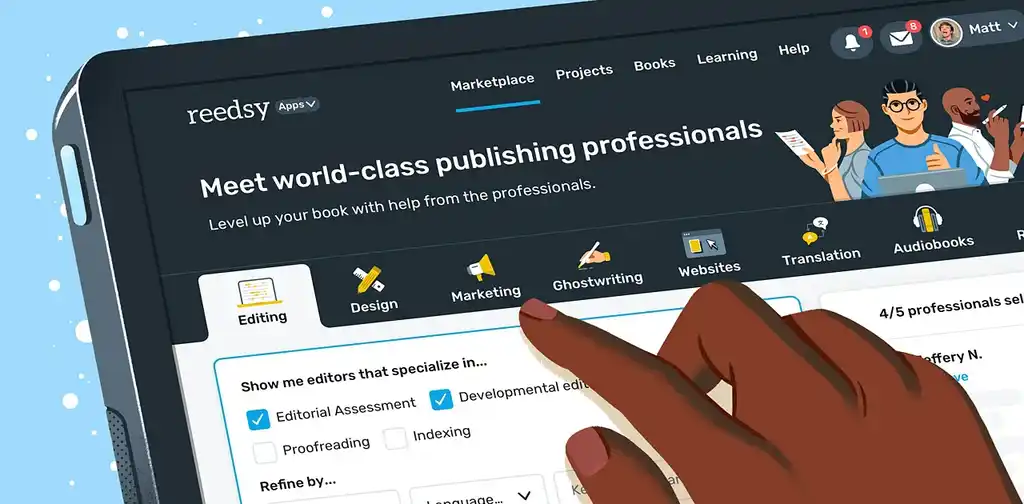

Fran: It depends on who you're freelancing for. If you're freelancing for an agency or for a publisher, there's one set of rules which apply only to the book, but if you're freelancing for Reedsy, it is also about keeping customers coming.

One thing I do is that I tell people to read my reviews because I'm actually not very nice. A lot of people like it the more mean I am. Some people need it. They like the frankness or they just like the punishment. But, I guess that's the thing: letting people know.

It's delicate because you want to be ethical and do the job, so recently I just called somebody in the middle of doing their manuscript and I said, “Are you going to be able to take this?” And I showed them a page. I said, “They're all like this.” And I reminded her that it was just us and that this is before it goes out into the real world where she is going to get creamed. So it’s like I’m their personal trainer. So when you’re working for Reedsy, it’s about the person you’re working for.

Martin: Jennifer, have you found something similar where you're working for a client and have a valid note that is absolutely true, but maybe you feel like you delivered it the wrong way, or in a way that wasn't helpful?

Jennifer: Definitely, that's one of the things I've learned. I touched on it a little bit earlier, but as an editor I really want to figure out who the person is, and as Fran said, I had no idea that when I became an editor that I was also a mother, a friend, a teacher, a hand holder, and a cheerleader, and all of these things that sort of come into play. So knowing what your client needs is important.

I have definitely learned to deliver criticism in a way that sounds friendlier than in my head. I can't say what I really mean, so I'm going to put it to authors in a way that won't make them feel defeated or that they shouldn't be writing. I try to be encouraging.

Mentorship and advice

Martin: Both of you talked about coming up through the New York system. Did you have mentors during that process that helped guide you and develop professionally?

Fran: I worked many places, so some of the mentorship I received was learning how to have tough skin. I worked for one person when I was pretty young and I did everything for her. She would say, “Did this go out like this?” and proceed to call me all sorts of names. Then five seconds later she would compliment my belt and tell me that we had to go shopping. Then there was another person I worked for where you could never say no to work: you had to do everything they wanted you to do. Then Writer's House was this beautiful place where I pinched myself to be working in a place with such nice people.

But that was a lesson in how to make it myself in this world and how to be tough and how to sell. In terms of learning actual skills, that came from working for so many extremely successful people — the best in the business really.

Martin: Your job is to give feedback, but who, on a day-to-day basis, gives you feedback?

Fran: Success, for me. If it sells and I'm making money and I'm growing an author from nothing to winning awards, that's my feedback. I know I'm doing something right and I get very confident and insistent that I'm right. That's probably something I need to temper, but I try to remember to tell people that my opinion is just one reader. I might not be correct. But even if you do a really bad job, you probably need the mindset of telling people that you’re right. Otherwise you just couldn't continue with the job.

Martin: Jennifer, did you have any sort of mentors going up through Scholastic?

Jennifer: I did actually. My boss who hired me based on my bookstore experience, was a true mentor to me. I did see some editorial assistants like myself who weren't as fortunate. So I consider myself really lucky because she taught me things that I needed to know, and she gave me a lot of chances.

But I remember in my second interview, she said, “Don't worry, I won't ever make you go get my dry cleaning,” and I thought, “Oh, is that going to be part of this?” But she really took her time with me and saw that I had potential, which felt great. And she was the editorial director of Scholastic Press, so she wasn't just anybody. She was pretty high up.

I made a ton of mistakes — everybody does — and I learned, and kept plugging along, and I loved it there.

Fran: I just wanted to tell one more story about this crazy woman that I worked for who was so hot and cold. I came to her with an idea for a book and said, “Have you ever thought of this?” It was for a non-fiction book. And she said, “That's a good idea, do it” And I said, “I can't do it, I'm not an agent.” But she told me “Poof, you’re an agent.” I think that was a wonderful little bit of advice: you don't need accreditation, you just need to do it.

Martin: Jennifer, have you had any piece of advice that stuck with you either on the craft side of being an editor or navigating your way through the business?

Jennifer: I do: not being afraid to have fun. It's a creative process. I know it's a lot of hard work, but it should also be fun. I feel that when I'm myself with a client, they relax. I can be myself, they can be themselves, and we can get through it together. One of the biggest things as an editor is building trust. If you're not someone your client can trust, they won't feel comfortable tapping into their creative process and letting you see what they're doing. They’ll clam up. So gaining somebody’s trust is one of the biggest things I do on Reedsy. I feel that when an author trusts you, there’s a connection that makes them feel supported.

💡 Building trust with your clients is crucial to tapping into their creative process, and having fun and being yourself can help create a relaxed environment where clients feel comfortable sharing their work.

Building trust

Martin: Does that trust mean that they feel you’re not keeping anything from them?

Jennifer: Yeah, I think that's part of it. I do tell them that I’m going to give honest feedback because that's who I am as an editor. I can't just write a couple of nice things and give feedback to somebody and feel like, “Why am I taking your money and why am I working on your story?”

So I tell them, “I'm going to give you difficult feedback that's going to make you work hard, but I believe in you and I believe in your project.” So just the fact that they feel supported, even though the work in front of them might be more difficult than they even imagined, is important.

Martin: Fran, you sort of describe yourself as a sterner taskmaster. How do you communicate encouragement and trust to your client?

Fran: I have Zooms with people and I think that it all starts to round out because I do have sincerity. It might not always be packaged well, but they'll see that I really worked hard, that I care, and that it wasn't fun for me to give them bad news. Then, the next thing we’ll do that I’m really excited about is getting on a Zoom and spending some time to brainstorm how to bring the beauty out of their writing.

Giving advice to your younger self

Martin: If you could go back and give yourself one piece of advice to your younger self, what would that be?

Fran: That the $2,000 wasn't worth it. I don't know what the starting salary is for editorial anymore, but this was in 1984 or something.

Martin: What did that look like lifestyle-wise?

Fran: Oh, I went out every night. Publishing houses are a lot of fun. The whole editorial department, the assistants are all about the same age. They're generally close. So I didn't notice that I was poor, but you know what — and this is part of the homogeneity — I also had a family that would help me. I didn't have that much to worry about.

Martin: Jennifer, is there a $2,000 you wish you'd taken or left?

Jennifer: I think I was too timid when I first started. There's this perception that an editor knows everything, but now I'll say to my client, “I have no idea what this is or what you're trying to do.” I'm much more willing to just say that I don’t know everything. I can help as much as I can, but there might be times that I fail and we'll just get through it together.

Martin: I think that's generally good life advice or professional advice, no matter where you work. Nobody knows everything.

Jennifer: Yes, just being OK with saying “I’m not sure, but let me find out.”

Q&A session

As a freelancer editor, is it absolutely necessary to have a degree in English or communications?

Jennifer: I would say no. I had a lot of friends at Scholastic who had very different backgrounds. It’s what I chose to study but it's not necessary.

Fran: Mostly you just need the experience. You need to have some sort of proof that you've successfully put a work into shape.

Martin: I guess if you're looking for an entry level job, a publisher might ideally be looking for someone with an English degree, but no company that I know of would give an outright no to someone just because they had a History degree or something like that. Usually, they’re just looking for good people who can do the work.

💡 You don’t necessarily need an English degree to become an editor, but experience and proof that you've successfully put a work into shape.

Can you share some of the current no-nos in publishing in terms of writing from different points of view?

Fran: It seems to be a fairly simple but broad answer: you can only write from your own socioeconomic, religious and cultural point of view. The character can move and have different adventures, but their demographic just can't be that different from yours.

I don’t know if that’s wobbling or not, but I think a lot of people are tired of it. I don’t necessarily agree with it all, but that’s what the industry is talking about, if you care what people say. I don’t know how pervasive those no-nos are outside of the New York publishing scene.

Martin: Jennifer, is it the same for children’s, middle grade, and YA?

Jennifer: Yes. It’s super sensitive. I work for some agencies as well and read their authors’ work and, to give an example, if I wanted to write a story and my protagonist was African American, there’s not one agent or publisher that would touch it. They want people who are African American to be writing those stories.

I see a lot of very well-meaning authors who want to bring diversity to their work, so like Fran was saying, it’s a discussion in terms of what your intentions are. Are you going to self-publish? Then you can put all the diversity you want in your book, though you might get some bad reviews. But from an agency and from a publishing standpoint, everybody's being super careful.

Most of my clients on Reedsy have no budget for publishing their book. The public's perceived value of our work as editors is about $20/hour. How do you address that?

Fran: Going back to that question of what I would tell my younger self, it would be to ask for what I deserve. I started out not charging very much, so I appreciate that Reedsy put out guideline rates that I can point to. Sometimes I tell clients that “my budget is flexible if yours is not” because that’s just my personal ethos. I know that people in the arts don't necessarily have a lot of money, and I have found that nobody has taken advantage of that.

Jennifer: My reviews are very good, and I work really hard for those reviews and feedback from my clients, so I feel that the edit that they’ll get from me is going to be fantastic. Over the years I've gained confidence to ask for what I think I should be getting.

I do have a lot of clients who can't afford it. To the ones who come to me and say, “I would really love to work with you but I really can't afford you,” sometimes, like Fran, if it's a reasonable request and we can work something out, like a payment plan, I might bring my price down slightly. But for the most part, I’m pretty fortunate to be able to ask for what I feel I deserve. And I find that most people are willing to pay.

I think Reedsy’s guideline rates are kind of unrealistic. Good luck getting even $25/hour.

Martin: Well, we’ve put those guidelines because people are willing to pay. We’ve found that having good reviews is really important and some freelancers that have joined us for webinars in the past have said that they put their rates up every three months until the work dries up, and were surprised to find that there are still many people out there willing to pay if you have the experience.

So, it’s not unrealistic, and most of the time, if you find that you can’t ask for the rates you think you deserve, it might be because your profile is not compelling or because you don’t have reviews. But there is a market out there.

Who can you reach out to if you want to start an editing career by reading the slush pile?

Jennifer: For now, people who want to break into publishing will have to do an internship. We had a lot of summer interns at Scholastic, and that's basically what they would do: read the slush piles. So that is your very first editorial position. As an intern or editorial assistant, you're the low man on the totem pole and it's a learning position.

Martin: What do you do with the things you read on the slush pile?

Jennifer: It depends on who you're working for. Whoever you are reading for will ask for either definite nos that you can go ahead and reject, maybes that you can sit and talk about, and yeses. But it really depends on who you're working for and what their policies are for handling submissions.

How do you ask people to write reviews?

Fran: I don’t do anything special to get reviews. I think Reedsy sends a reminder to authors to leave a review. Occasionally, if I get along really well with the author, I will ask for a review, but I only ask if I know that they're going to give me a good one. Otherwise, I just leave it to fate.

Jennifer: In the beginning, I would ask people who I had a good relationship with to write a review, but I don’t want to pressure anybody into it. I want them to write it because they had a great experience with me.

I find that maybe half of my clients leave reviews. I know it's tough. You're asking somebody to take personal time and thought to do that for you, but I always make a point to thank them very much. And I feel the more communication you have with the client, the more they feel that you're on their side and that you’re giving extra value to your collaboration, the more likely they are to write a good review. That’s just my experience.

How can I expand my client base as a freelance editor?

Fran: I went straight to freelancing via Reedsy. You know, proof is all you need.

Martin: To pull back the curtain a bit, at Reedsy we are looking for people with at least three years of experience at a traditional press and a list of books within your stated genre which have been well received.

🤓 You can read more about Reedsy’s selection criteria here.

Jennifer, have you freelanced elsewhere or on your own shingle before?

Jennifer: I have not on my own shingle. I always said that if my editing work would dry up, I would go ahead and do that, but I came from traditional publishing, so once people knew that I was leaving, I received a lot of interest from both agencies and other publishers who knew me and knew my work, to freelance for them.

Now, I sort of pick and choose what I'm going to do because I only have so many hours in a day. Reedsy is probably about 90% of the work that I do and the rest is just from past relationships that I’ve maintained.

How can you trust an intern who has very little editing experience to read the slush pile and judge what would make a good book?

Fran: Well, just like a literary agent and a publisher have a sense of who is a talented writer, they have a sense of who is a talented reader. It’s not easy to become an intern. It’s very competitive. It’s not ideal, but it’s better than never reading the slush pile at all.

Do you use any specific style guides to help you edit?

Fran: I don’t because I’m actually mostly in developmental editing so people have a long way to go before they’re down to that level. But I also have what is correct and what is possible in proofreading pretty much down.

Jennifer: I just use what I learned at Scholastic. I pretty much have a style and it’s in my brain, but I also do mostly developmental editing and almost no proofreading. That's a very specific job.

How would you recommend editorial assistants learn to edit considering they're not given formal editorial training?

Jennifer: I feel that it's the sort of thing where you, as an editorial assistant, will not be on your own and you will never have your own book, not for a while. So, for example, I worked closely with my boss. I would read something, she would look over my comments, she would comment, and it was more of a process. And in seeing how she edited, I learned to develop my own style, what that even meant, and how to give authors comments and that sort of thing. So you aren't just left to your own devices. You will have somebody who's above you, showing you the ropes until you are able to acquire your own projects.

Martin: Most of the things you will learn on the job by seeing other people do it enough times and sort of picking it up. A lot of people assume that there are courses you have to complete or exams to pass, but a lot of it is just showing that you can do the work and have people trust you.

I think that’s the end of the webinar. Thank you very much for tuning in everyone and to our guests for joining us. Hope to see you all very soon. Goodnight!

For more professional insight on topics like on how to showcase your experience, get more freelance clients, or notifications about events like this, subscribe to our Freelancer newsletter or follow us on LinkedIn.