Blog • Understanding Publishing

Posted on Jul 16, 2025

How to Get a Book Published in 7 Steps

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →To publish a book, you typically have two options. You can either take the traditional publishing route via an agent and publisher, or self-publish through online platforms.

The traditional path requires finishing your manuscript, locating a literary agent, and then collaborating with said agent to present your book to publishers. Self-publishing, conversely, enables you to manage the complete process independently, from editing and formatting to marketing and distribution.

In this post, we’ll walk you through the traditional publishing route — the path most writers imagine when they think of “getting published.”

How to get a book published:

🎲

Is self-publishing or traditional publishing right for you?

Takes one minute!

1. Finalize your first draft

Many fiction authors wonder if they can land an agent or publishing deal with just a proposal. Unfortunately, unless you're already an established name with a proven track record, you’ll need a fully finished manuscript before approaching agents or publishers.

This can’t be just any finished draft — it needs to be the best version of your book! That means you’ll need to let it rest for a bit, then revise it thoroughly, fixing any structural flaws, plot holes, or pacing issues before you hit send.

Since self-editing is notoriously difficult, consider working with beta readers — people who love your genre and can offer honest, outsider feedback.

Q: Can a beta reader replace a developmental editor?

Suggested answer

Nope, a beta reader can’t replace a developmental editor—and here’s why:

While beta readers are awesome for giving general feedback from a reader’s perspective (like plot impressions, character likability, or whether the pacing kept them turning the pages), they’re not trained professionals when it comes to deep story structure and craft.

A developmental editor dives much deeper. They analyze the bones of your story—plot arcs, pacing, character development, themes, structure, and consistency. They help shape and fine-tune your narrative to ensure it’s compelling, cohesive, and working as a whole. Their feedback isn’t just “I didn’t like this part” but more along the lines of “This subplot doesn’t serve the main storyline—here’s why, and here’s how you might tighten it.”

Beta readers provide valuable insights, but it’s more like a test screening for an audience’s reaction. A developmental editor, on the other hand, is the director who helps get the story in top shape before the curtain even rises. Ideally, both roles are helpful, but they do very different things—and one shouldn’t be seen as a substitute for the other.

Eilidh is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No.

A beta reader can give you a subjective opinion on your story; a developmental editor can give you objective advice on how to strengthen it.

Beta readers are a great place to start. You can see what issues and questions come up for readers and take some steps to self-edit . But this will never be a replacement for a professional assessment.

Margot is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. While a beta reader may be able to spot some weaknesses, they don't have the expertise to help a new author implement the needed changes that will help the book become strong enough to be published.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I may have a different opinion here. I was a beta reader and critique partner before becoming an editor, and that experience helped me hone my skills. If you have an excellent beta reader who spends a lot of time studying the industry and does this a lot, that may replace a developmental editor, particularly in traditional publishing, where your book will go through many more rounds of editing before it is published. (But the book still has to be excellent before you get an agent or editor!) However, "beta reader" is generally used to mean a person who gives an author relatively quick thoughts on a book. They may be able to speak to things they personally liked or didn't like, but not separate whether that's personal preference or a real problem with the book (to be fair, editors struggle with this too). They may be able to point out something that isn't working, but struggle to suggest ways to approach the problem in search of solutions. Also keep in mind that beta readers are generally reading for free or sometimes a very low cost. In my developmental edits, I provide thousands of comments (depending on length). Is it really fair to ask someone to do that for free?

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. It's in the name: beta reader... A good beta reader gives essential feedback from the position of a reader.

I am a developmental editor... I give essential feedback from the position of a professional editor with decades of experience doing so.

I appreciate and respect an author who has taken the time and effort to acquire feedback from a beta reader.

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. A beta reader by definition is a non-professional who is a fan of the genre, who provides a reader's-eye view of the book. How did they experience the story? What were their emotional reactions? Were they confused? Were there things they particularly liked? They're a test audience so the author knows if they achieved what they set out to do. A developmental editor, on the other hand, is an experienced pro who can not only identify issues but offer ways to address those issues while bringing a breadth and depth of experience and perspective that amateurs cannot. Beta readers are volunteers offering opinions, while developmental editors are paid professionals offering solutions.

Elizabeth is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

These are often fellow writers or dedicated readers who can give you a valuable “vibe check.” If they find parts of your story confusing, slow, or inconsistent, your book probably needs more work before it’s ready to query.

You might also want to bring in professional editors — both developmental and copy. A pro edit can make all the difference when an agent finally reads your manuscript. It’s an investment, but one that often separates a rejection from a request.

Q: What should clients expect in terms of feedback and revisions during a developmental edit?

Suggested answer

With a development edit, what I'm giving you is a full health check and service of your novel. This is a close, hands-on edit of your story, focusing on narrative development, characterisation, dialogue, story-telling, and the clarity of your authorial voice and your prose. Essentially, my aim is to help you get the best out of your novel and give you the best advice possible. With several decades' experience working in genre publishing, I have an excellent idea as to what markets are out there and where to best place your novel.

You can expect to receive the edited novel with my changes tracked and comments included. Through the tracked changes you will be able to see my advice on what you can change and consider in revising your novel. I always track changes, as a development edit is a collaboration with the client. I'm using my extensive experience to make judgements on what works and what doesn't, but at the end of the day you have to be happy with those changes, and that they are true to your vision for the work.

As well as the full edit, I also provide my clients with a copy of the chapter and style notes I make as I edit. These are an immediate record of my process, showing my thoughts on each specific chapter. Clients also receive an editorial table, which is what I use to keep track of the spelling of names, unusual/unique terms, and places in the novel, as well as keeping track of essential characteristics, such as hair colour. I also provide my clients with a book report. This is an overview and analysis of the novel, detailing my key findings and suggestions as to revisions the client can consider and what next best steps they may also consider.

Finally, I offer to follow up with my clients in a one hour Zoom or Skype call, which is their opportunity to ask me any further questions they may have, as well as to discuss my edits in detail.

Jonathan is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I define a developmental edit as a comprehensive review of a book’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for revision. With your manuscript, I’d read it and consider its pacing, plot, character development, voice, and other building blocks of storytelling. After reading the draft, I’d deliver to you a detailed editorial letter (no shorter than 3,000 words). The other "deliverable" from this service would be a detailed annotation of the manuscript. Using Track Changes, I would point out in-text examples of what's working, what's not, and potential paths forward as you continue shaping the manuscript. I find that this tool can be especially helpful for authors who want specific examples identified for them throughout the text. My expectation is that these two deliverables can help you improve the current manuscript while also adding to your knowledge base long-term. Hopefully, they’ll be resources you can revisit again and again.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A nose-to-tail structural edit of your manuscript for authors who have taken their book as far as they can by themselves.

- Detailed recommendations to improve “big picture” concerns like characterization, plot, pacing, setting, etc.;

- Specific guidance on elements of writing craft;

- In-line suggestions and edits in the manuscript.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A developmental edit includes an analysis of what is working and what still needs to be improved regarding big-picture issues like pacing, plot, clarity, setting, telling vs. showing, character development, etc. I provide suggestions for improvement directly on the manuscript using track changes in Word. I also include pages of editorial notes regarding what still needs to be improved and I provide suggestions on how to improve these issues. I am also always available for Zoom chats before, during, and after any edits are provided. And clients may contact me at any point in the process regarding any questions or concerns, even after the collaboration has officially ended.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

My developmental edits include two parts: line notes and a letter.

The line notes point out any strengths or issues that arise as I read. For full-length books, generally, these line notes will even out to about 1-2 per page, though some pages may have none, and some pages may have many, as needed. For shorter pieces and picture books, I typically include many more line notes per page, depending on what is needed. When I notice a repeated problem, I discuss it in my overall letter rather than commenting on every instance. These line notes are meant to educate authors and help them become better writers, not "fix every error" as a copy edit would.

For full-length books, for the letter, I normally include:

- An introduction discussing the book's high-level strengths and opportunities for improvement.

- Sections discussing structure/plot, character, setting/worldbuilding, romance if applicable, target market (age category, genre, and comp titles), title, and style.

- A conclusion with key next steps to focus on for the book.

These letters are lengthy, generally in the ballpark of 3,000 words (10-ish pages), and come with a table of contents.

My letters for shorter pieces and picture books are shorter and less formal, though they include roughly the same sections.

My developmental edits also include back and forth via message for 6 months after the project is complete. I love to brainstorm and talk through issues!

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Hire an expert editor

Andrea R.

Available to hire

Empathetic editor of award-winning picture books and middle-grade fiction. I bring a thoughtful approach to story, pace, language, and tone.

Frances G.

Available to hire

Children's editorial director at a "big five" publisher, with 31 years of picture book experience. Author of ten published children's books.

Mark L.

Available to hire

I'm an editor and manuscript assessor, and passionate about making your novel ready for the market. My clients include #1 bestselling books.

If you’re writing a nonfiction book, things are a little different. You actually don’t need a finished manuscript, but a polished book proposal. This includes sample chapters, an outline, market analysis, your author bio, and a marketing plan 一 basically the proposal should sell your idea.

Once your manuscript is looking sharp, the next step is compiling a list of agents to pitch.

2. Shortlist the agents to pitch

You might ask yourself: do I really need an agent? Can’t I just pitch my book to publishers?

While some indie presses accept “unagented submissions,” you’ll find that your best bet to score a traditional publishing deal will be to secure an agent first. Not only do they have the right connections at publishing companies, but they will also know how best to sell your work to acquiring editors.

Q: How do editors and agents evaluate whether a manuscript has commercial and craft potential?

Suggested answer

Potential is usually obvious in the first few sentences. The quality of the writing, pace and tone particularly, are evident from sentence one. But structure is important too, and if that's not in place, no amount of fine writing is going to fix it. So fine writing + tight structure (whatever these things look like in any given novel) is the clue that the manuscript has potential.

Potential is all about a writer being in control of their material. A writer I feel confident in from page one. The sense that although the manuscript isn't perfect and needs work, the writer fundamentally knows what they are doing. I look for a tone that fits the genre. This is really important, and often it's not working in manuscripts. Good pace is important too, again whatever that looks like in any given novel. This is often determined by the genre. For example, thrillers are pretty much defined by their fast pace, yet I've read many manuscripts described by their writers as thrillers that simply aren't, often due to slow pace.

Potential in a manuscript is always an exciting thing to find as an editor, and it is usually evident where a writer understands their genre, its pace, and its tone. That is a very strong start!

Louise is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The first thing I consider in a manuscript is how well the first line caught my attention and made me truly care. Even if is subconscious, readers are passing judgement on a piece immediately. This is why the first line is absolutely vital to setting up a successful manuscript. Unfortunately, most people have a very short attention span, and over 500,000 new fiction books are published each year, leaving no shortage of choices for readers. If a writer is adept at capturing an audience in just one line, it tells me they likely understand storytelling and know how to craft a narrative with a compelling voice.

Beyond this, I see potential in consistency. By this, I mean I always look for consistency in the voice throughout a manuscript and for characters to remain consistent in their choices or motivations. If characters are constantly doing strange and out-of-character things, it tells me the work is not well planned or fully developed. I look for plot consistency as well: is the central problem remaining the central problem, or have things drastically shifted somewhere along the way? If it has shifted, it is a sign that the original plotline/idea may not have been strong enough to carry the story.

I hope this helps! There are quite a few other small things I look for, but these are the two biggest ones I can typically spot right away.

Ciera is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Pitching your book is just one of the many tasks that falls to an agent. They are also advisors and editors, who will give you objective advice on your manuscript and act as a buffer between you and the publisher. They’ll handle a lot of the business side of things, leaving you free to write.

Most importantly, they are deeply familiar with the industry and should know how to negotiate the best price for your book (and avoid potential scams). For that reason alone, they are worth their commission (which is usually 15% of your gross proceeds).

Where to find an agent

So where do you find an agent? There are several free directories you can consult to begin your search.

Here are some of the best ones:

They all let you filter by genre, location, and openness to debut authors. They also highlight key info like genres, track-record sales, response times, and submission windows, so you don’t have to query “blind”.

Q: What unexpected skills do you need as a literary agent?

Suggested answer

PATIENCE.

Patience is key in a literary agent role. Writers hear all the time that they need to have patience when writing, editing, querying, and going through the submissions process (assuming they sign with an agent and their manuscript goes out on submission). Sometimes, it doesn't happen with the first book or even the second or third. Patience, persistence, and perseverance are super important for writers.

But the same goes for literary agents. It's very easy to get frustrated with the lack of movement in this industry. We're constantly waiting to hear back from editors on submissions, to get through the contract negotiation process, to hear back from various departments so that we can ensure the smoothest and most efficient process for our clients. It can take 18-24 months to get a book launched and out in the world from the time the contract is signed. The publishing industry is far outweighed by the sheer mass of writers there are out there, and there just aren't enough of us to keep up in a timely manner in most cases.

We do our best though, and we have to remember that editors, publishers, the sales team, the publicists, and all the other industry pros involved in the publishing process are doing their best, too. Everything will happen when it's meant to. :)

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

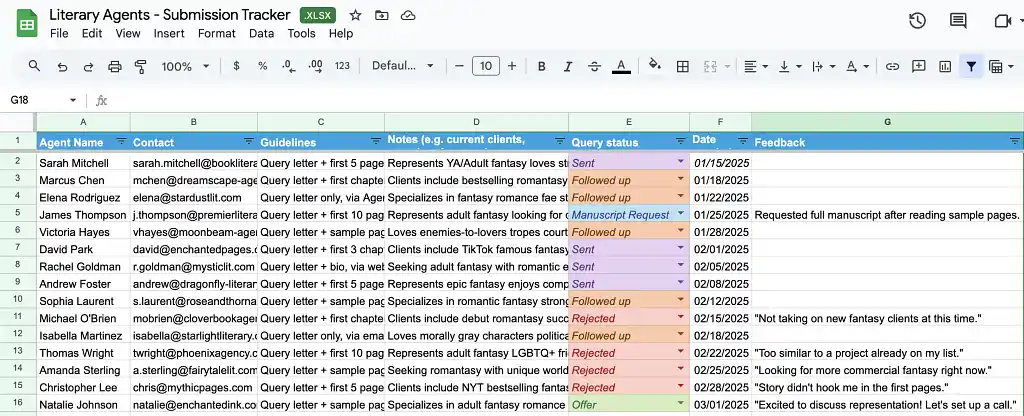

Curate a list of vetted agents

Once you’ve gathered a few viable names, double-check that your story’s genre, sub-genre, and commercial hook genuinely match theirs. Study their client lists and verify that each agent is currently open to queries.

Build a spreadsheet of roughly fifty to sixty prospects so the inevitable rejections don’t stall your campaign.

Q: Do you have any words of encouragement for authors struggling in the querying trenches?

Suggested answer

First of all: don’t give up. Rejection isn’t the end of the story—it’s part of it. Every “no” is simply a redirection toward the right “yes.”

Publishing is absolutely a business, but it’s also deeply relational. Editors and agents love working with people they genuinely like and trust. That means: go to writers’ conferences. Join a critique group or hire an author coach. Get to know professionals in the industry, not just for what they can do for you, but for how you can show up as generous, authentic, and collaborative. You never know when a writer friend might one day endorse your book, or when a connection you make over coffee might become a career breakthrough.

And here’s the bigger truth: querying is more than chasing contracts. It’s also a personal growth journey. You’ll discover your resilience, refine your craft, and grow into the writer you’re meant to be. One author I know literally turned her pile of rejection letters into a lampshade and said they helped light her way to publishing three novels.

Need more inspiration? Catherine Stockett, author of The Help, was rejected by 50 agents before one finally said yes. That “yes” led to a book deal, a bestseller, and eventually, a movie.

So hold fast to your dream. If you feel called to write, you probably are. Keep writing. Keep connecting. Keep becoming the kind of author people want to root for. The path may be long, but you’ll be stronger, wiser, and more yourself because of it.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Querying can be emotionally challenging and overwhelming for authors. Once you're in it, you're amongst a sea of probably tens of thousands of other authors at the same time, and there are, of course, only so many agents and agencies out there. Truthfully, the odds are not great; an agent will sign only about 1-3% of the authors they come across in their queries. This is why the query must be in tip-top shape: a query's only job is to make the agent curious enough to ask for pages. Then, they have to fall in love with the pages (the writing and the story, which are two different things) and have a vision for it in the current market.

If you go into it with the right mindset, it can make it easier. Expect to receive many passes; it's inevitable in 99.9% of cases. Your story isn't for everyone; no one's is. And there are so many reasons an agent might pass. Try not to take it personally; if they pass, then they were not the agent for you. You have to have thick skin though. Not every agent will reply, and if they do, they may give feedback or a reason they're passing or they may not. It's hard not knowing, but there's not much you can do about it. Agents are not paid for the time they spend on queries, and their top priority is the clients they already have, so unfortunately, queries often fall to the bottom of the priority list. And because we receive so.many.queries, it's very difficult to stay on top of them all. We simply don't have the time to respond to everyone. All you can do is do your best; ensure your query is spectacular so that it stands out, your pages are spectacular so agents see it as ready or nearly ready for submission to publishers, and research the agents and agencies first so you know you're shooting your shot with the most appropriate people in the industry. Follow their submission guidelines, don't cheat, and be friendly and professional. Get several pairs of fresh eyes on your query so you know it contains all the necessary elements (and doesn't contain anything that shouldn't be in it) as well as your manuscript, and make sure everything is ready before you begin querying. Being prepared says a lot about your work ethic, which is important to agents as well

It sounds cliche, but the only difference between those who find representation and those who don't is that the authors who found representation didn't give up. It takes patience, persistence, and perseverance. And it may not happen with your first completed manuscript, or even your second or third--but if your goal is to find an agent and be traditionally published, keep going. Keep learning, keep trying, keep connecting with other writers and industry pros. You've got this!

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Don't be afraid to tear up your query letters and start again. Be aware of the time of year -- you may be going 24/7/365 but agents and publishing houses don't do that. Check out Writer's Digest articles on query letter writing and examples of winners and losers. Check out Query Shark. Understand the different agent types and editors at small presses -- different query styles may be required. Send queries out, mark the calendar 4 weeks from that date, and forget about them until then.

Query letters are not a sales letter about you -- you love your book, your letter needs to make anyone want to love your book as well. :O))

Check out writing blogs/websites such as those of folks like Anne R Allen or Janice Hardy -- or any author you admire -- their tips on query letters may include something you've never considered.

Start your next book... c'mon! You might be surprised what's waiting to pop outa your head!

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Querying is so tough these days! There's more agents than ever before, but yet imprints are folding, combining, etc. so the number of projects being sold hasn't increased, making it harder to catch an agent's eye.

There may be any number of reasons you're not getting full requests--your query letter doesn't capture the unique quality of your book making it stand out, your first pages fall flat and don't pique the agent's interest, or, quite simply, the agent isn't interested in your characters or plot. And there's nothing you can do about that last one. Every book isn't for every person. Every agent has meh topics they rather not read about. If an agent isn't into mermaids, they're unlikely to request a full from a query that describes a book about mermaids. That query was never going to land a full, and there was absolutely nothing about the query or your writing that could have changed that.

So, concentrate on what you can control and push aside the rest. Querying is not a comment on your worth as a human or as a writer. Publishing is a fiesty marathon. If your current project isn't getting bites, write the next thing. You'll improve with each project. Trust that the stars will eventually align when your idea and words will pack a punch. How can you make your project stand out as unique? What tropes can you put a spin on? Create characters we can't help but root for. Lean into what you--your background, your hobbies, your experience, can bring to a project that springs it to life in a way that can't be replicated.

But above all, know that it's not just you--the struggle is real for many, and the only thing you can do is simply keep writing.

Kim is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Don't lose faith!

I know that's easier said than done but try not to let rejections get you too demoralized. Most best-selling authors had the same struggle and likely went through many rejections before securing a deal. Unfortunately, it's all part of the process.

If you are getting form rejections then it is likely you are either choosing the wrong agents or there are issues with your query pack, so make sure you put as much work as possible into researching who you want to pitch to and refining your documents. Don't rush into querying. This is your one shot to catch the attention of that agent, so you want to get it right.

If you are getting requests for your full manuscript then you are likely on the right track and have a good submission pack. Don't be afraid to ask for feedback, but agents are very busy so you may not always get it.

I would also encourage you to keep writing while querying. Authors often get their second or third book picked up instead of the first one they queried, so don't lose hope. If you are tired of the rejections then use any feedback you have been given to write something new. There are no guarantees, but keep working at it and hopefully you will find your perfect agent eventually.

Finally, be kind to yourself. A rejection doesn't mean your book is rubbish - it just means that the agent can't see a place for it at this point in time. Many, many, many brilliant books have been turned down initially and then had great success when they found the right home. Don't give up hope.

Amy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Remember, you are not just looking for any professional agent who’s willing to take you on. You want one that’s right for you and your manuscript. They should be passionate about your book. After all, they’ll be responsible for selling it! On that note, don’t dismiss ambitious new agents attached to reputable agencies — they’re often hungrier and have lighter client loads.

Finally, watch out for submission quirks like required page counts or preferred platforms. Some agents want queries via email with a few sample pages, while others use QueryManager and may request full chapters. Always follow their guidelines to the letter!

Speaking of letters…

3. Write a strong query letter

You need to beat the competition and win your agent’s interest. Think of your query as a one-page sales pitch: under 400 words, laser-focused, and built with a structure that agents can scan quickly.

Q: What are the most common mistakes authors make in their query letters, and how can they improve them?

Suggested answer

One of the most common issues I see in query letters is the tendency to skip over who your main character is as the book starts. You want to show the agent who they’re going to be reading about and give the agent a reason to care about what happens to them. That’s your first paragraph (not including personalization or comp titles if you choose to put those at the top). Spend two to three sentences describing your character, their personality, their future plans, their desires, etc. That way, when the agent gets to the second paragraph and you throw chaos into the picture, they’re already thinking, Wow. How’re they going to deal with that?

Example:

Sixteen-year-old farm boy Luke Skywalker would do anything to leave his uncle’s dinky desert farm and attend fighter school with his friends. The evil empire is rising, and he wants to do his part to make the galaxy safe. But until his uncle agrees to foot the bill, Luke’s stuck cleaning the farm’s droids, a far cry from the adventure he seeks.

With an opening like this, you’ve established who we’re rooting for, his desires, and his ultimate goal. In the next paragraph, you can then drop the inciting incident, i.e. the thing that gets the story rolling.

Example:

Mary Collins is free of her wretched husband, their divorce finalized after a grueling three years where he fought her on every detail. Finally, Mary can leave the city where it was so important they live and return to her hometown. Helping her mom run the corner store while catching up with friends and family is the bliss she seeks as she starts over, now free of the myriad of obligations that came with being the governor's wife.

My guess is that Mary's going to find she's not so free of her past life once that second paragraph comes around. But because we know that's her desire/goal, it makes it that much more meaningful when the query then continues to throw havoc her way.

Giving us info about the character is important no matter your genre and age category.

If your book features a police officer, give us a bit of their background so we understand their current situation. That way, when chaos reigns, we know why that particular wrench is so bothersome. If a cop is trying to get promoted, being thrown into a big case is a dream/chance to show off. If a cop is near retirement, the last thing they want is to be trapped in a big case. Without knowing the main character’s background, your query is all about plot and you’re losing the character.

Agents, like readers, want to root for someone. They want to become invested in your character—so give it to them. Show them who they’ll be reading about and make them care. Then in the rest of the query, you can weave in those plot details and stakes.

Kim is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I like seeing the title, genre and comp titles at the top. Often, writers hide this info in the final paragraph. I want to know immediately what this book is and what it's about, along with where it could sit in the market. It quickly tells me if this book is for me and if the author even knows what their book is about.

Another misstep is writing far too much in your plot paragraph. It really should only be 1-2 short paragraphs. Think plot/premise/payoff. This is probably the hardest part for writers. You are very close to your own work and might feel overwhelmed by condensing the entire narrative into a handful of sentences. When I receive a query, I'm looking for your main character, their world, what has changed in their world, twists or turns along the way, and even a question you might have for the reader.

For bonus points, add a logline before your plot paragraph(s). It's an efficient way to hook the person you're querying.A query letter should be no more than one page. Finally, look up the agent or editor's name and address it to them with the correct spelling. First names are preferred. It feels old-fashioned to address a query with Mr, Mrs, Ms, etc.

Ariell is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A lot of query letters are too long. An agent will spend perhaps one minute scanning through your query letter, so make it easy for them to find the important stuff. And don't spend too much of your word count on the summary! The goal isn't to tell the agent everything that happens in the book; the goal is to mention enough selling points and hooks that the agent is intrigued and starts reading your sample pages. This means one, maybe two paragraphs of summary, in the basic format: "[Protagonist] wants [motivation], but [obstacle] gets in the way. They'll have to [challenge] if they're ever going to achieve [stakes]."

Nora is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think that authors are sometimes so keen to get on board with a particular agent that they forget to keep their letters concise and professional and often volunteer personal information and background information that doesn't have a place in a query letter. The other thing I often see is authors including what almost amounts to a full synopsis of their book, whereas this should be presented in a separate document.

Vanessa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Three words: be more specific.

The standard advice used to be: look to a book's back jacket description for an example of how to describe your book in a query letter. The truth is, over time, the trends in queries have evolved AWAY from what's used on the back cover of books. Book jacket descriptions tend to be more vague, and focus on general claims like, "a thrilling coming of age story." Also, book jacket descriptions often end with rhetorical questions like, "Will Eva find love before it's too late?" but rhetorical questions in a query tend to be an agent pet peeve.

Most of all, agents don't want to hear that you have a "sweeping love story." They have 50 other sweeping love stories in their inbox right this instant. They want to hear the SPECIFICS of your setup, conflict and stakes to know how your love story stands out from the others, or they'll be getting out the broom to sweep your query right back out of their inbox!

Michelle is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A couple of the most common areas I see authors make mistakes in their query letters include:

- Not using proper query format

- Making the Book section (what your book is about) section either too long or too short.

While there is some variation on a query format, the one I like to use is the Hook, Book, Cook method.

- Paragraph 1 is your Book. What the title of the book is, the word count, why you decided to pitch the agent, comparable titles, etc

- Paragraph 2-3 is the Book. Think of this like the blurb on the back of a book or on Amazon. You want to give agents just enough information that they want to know more, but not give the ending away. That's for the synopsis, as is going into greater detail about the character and story. For the query, focus on the primary characters with their primary goals and motivations, the overarching conflict and villains, and set up the stakes of what the heroes will lose if they fail

- Paragraph 3-4 is the Cook. You as the author! If you don't have any prior writing credits, that's okay. Include a short paragraph about what you like to do, or what you enjoyed about writing the book. If you do have prior writing credits, try to only include those that are most relevant to what you're pitching (example, it's likely not applicable to share that you had an article in a cooking magazine if you're pitching urban fantasy, unless that ties in some way).

When writing the Book section of the query, I often recommend to authors to go into their local bookstore and seek out books in your genre with descriptions you like. See how they introduce characters, conflict, what details they do (or don't) include. Emulate them with your own story. Queries can be difficult, but with practice they do get easier!

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Common mistakes in query letters:

- Not saying what your book is about and why your target audience will love it.

- Remaining a secret writer by not sharing who you are, your background, and your writing experience.

- Giving away too much of the story: Mr. A hates Mr. B and winds up killing him.

- Making assumptions about the publisher, the books it publishes, and those it doesn't.

- Making unrealistic promises: This book is going to be a best seller with 500,000 books sold this year.

Barbara is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There are a few common mistakes you can avoid when writing your query letters. Here are some "do's" and "don'ts."

- Include only your first and last name in the query. The agent has your email address, and that is the address they will use if they wish to contact you. Do not include any other contact information (unless requested).

- Address the query letter as the agent stipulates on their website. If they do not specify their preferred salutation, use their first name and last name, e.g., "Dear Jane Doe."

- Make your first sentence about what you and the agent have in common (e.g., "Dear Ms. Smith, On your website, you say you like working with authors who (fill in the phrases the agent used), so I'm excited to present my (state your word count, genre, and BOOK TITLE IN CAPS)."

- State your comps (competitive or comparative titles) in your first paragraph. With your comps, try to use one book that this agent represented. Don't use best sellers as comps. Don't use books published over 2 years ago (and not over 3 years) as comps. Be current. Do your research. If you can't find recent comps, do more research. Read every book you use as a comp. (As you read your comps, make notes about how each comp is like your book, and how it is not like your book. You'll need this information for your book proposal (for nonfiction), and you'll need to talk about this with the agent when they call you.)

- Make your query letter 300 words. Why? Because a 300 word count is industry standard. Because 300 words is what many agents allow for their online submission forms. Because 300 words (single-spaced) will fit on one printed page, in case the agent prints out your query. Because if you can write an interesting query letter in 300 words, the agent will know you're a pro.

- Format your query according to industry standards: single-spaced, left justified, 2 spaces between paragraphs. No tabs or indents. No bold or underlining. Put your book title in CAPITAL LETTERS.

- When emailing your query, always drop your letter into the body of the email. Never send it as an attachment, unless requested. Don't send a query snail mail unless requested. Write in the email Subject line as directed (e.g., "Query - Title of Book - Name of Author.")

- Don't follow up on your query letter (unless an agent has invited you to submit to them). If you have sent an unsolicited query, if an agent says on their website their response time is four to eight weeks, and at eight weeks you haven't heard from them, query other agents (but not in the same agency). No response from an agent is a "No." Don't take it personally ... just move on. Your perfect agent is out there, waiting for your query letter!

I wish you every success with querying.

Michael is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

One big mistake is querying the wrong agent. Sending your 90,000 word adult fantasy to an agent who specializes in literary nonfiction will only result in a rejection. This does not mean that you do not have an amazing story, but rather that that particular agent cannot best service that particular story. As a writer, make sure to do your research to find the best agent for your work.

Hope this helps!

Samantha is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

To master the craft of writing an outstanding letter, check out our post on the topic as well as these query letter examples. But in a nutshell:

Open with a clean greeting (“Dear Jordan”) followed immediately by your book’s title, genre, and rounded word count — then deliver a hook that spotlights your most irresistible premise, conflict, or question.

Follow the hook with a 1–2-paragraph mini-synopsis that reads like back-cover copy: introduce the protagonist, the disruption to their world, the stakes if they fail, and a glimpse of the journey ahead. Keep this (and the hook) to roughly half the letter’s total length.

Close the pitch section by naming one or two recent comp titles (“X meets Y” or “For fans of…”) to prove you understand where your book sits on the shelf — avoid mega-hits, ancient classics, or obscurities that will confuse the agent.

Next comes your author bio. In two lines, highlight any publishing credits, awards, professional expertise, or platforms that bolster your credibility. If personal experience uniquely qualifies you to tell this story, mention it here.

Finally, personalize it. Show you’ve researched the agent by referencing a client, wishlist item, or a potential interaction you had (whether in real life or online), then thank them for their time and sign off. Before you hit send, triple-check submission guidelines and consider a professional query-letter review.

Q: How does personalizing a query letter improve request rates, and what should be tailored?

Suggested answer

I'm more concerned with whether your query letter hooks me: I want your title, genre, word count and comp titles at the front. I am even curious to know why you are the exact person to write this book (e.g., 'I'm an arctic research scientist so I set my locked room mystery in a research base', etc). You can put info about yourself in a very short about section in your sign-off paragraph. That said, it doesn't hurt to include something specific to me. For example, suppose you listened to an interview where I said I'm interested in finding a particular type of novel that yours fits with, or you connected with something I posted on social media. In that case, it's good to include this. It makes me think you are keen to work with me and aren't just randomly querying. But with that said, as long as you address the letter to me and then write a strong, gripping query and telling me a small amount about yourself and what that means to you as a writer, I'm less concerned about you including extra personalisation directed at me.

Ariell is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The baseline requirement is that you need to address your query to the agent's name; "Dear agent" letters sent out as shotgun emails to five hundred agents will get rejected quickly. Beyond that...my usual suggestion is to offer one or two sentences at the beginning of the query letter showing that you've done your homework. This can be as simple as "I saw on MSWL that you're looking for more multi-POV novels," or "I saw on your agency website that you're interested in cozy fantasy." This shows that you're respecting the agent's time by making sure that what you're sending is aligned with their tastes at the most basic level. Agents know that you're probably querying about ten people at once, and they're receiving perhaps hundreds of queries a day, but the personalization makes it a little more likely they'll spend some extra time looking at yours.

Nora is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think a personalized query letter achieves the same aim as a piece of handwritten, personalized mail: it shows the sender has put thought and intention into what's enclosed.

As a small-press publisher, I certainly understand that manuscript submitting is a numbers game. Authors have every right to query their manuscripts to dozens of publishers and agents simultaneously. But no one wants to be treated like a row on a query tracking spreadsheet! Dear Sir/Madam, to whom it may concern, generic language about the submission's fit within my company's catalog of publications: these tactics suggest the author is taking a slapdash approach to submitting.

Conversely, when a submitting author can demonstrate their familiarity with my press, it comes as a huge relief to me. Of course, I don't expect every submitting author to buy a copy of book I've published before firing off their manuscript. But if an author can reference a title from my manuscript wish list, or if they address me by name, or if they can say in 1-2 sentences how their book aligns with my company's mission statement, then that goes a long way!

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Because many authors want to increase their chances of representation, most send out lots and lots of queries letters all at once using some form of template (Dear Agent, I'm seeking representation...). While using a template like this does cut down on time, some agents get hundreds, if not thousands, of query letters a month! What's a way you can stand out from that? Personalize the query.

Agents want to know that you, the author, not only have a good book worth pitching, in the genre the agent works in, but that you have put in the time and effort to learn why they specifically would be a good fit for your work. An author-agent partnership is not a one and done thing, but ideally and ever-growing relationship that starts by being a good fit for one another. And so, showing that you researched them by personalizing a query expresses that:

- You have done your research for that particular agent, and so take your craft seriously

- You know what they represent so are pitching them in a genre they actually represent

- Have likely researched their other clients so you have a reasonable idea of whether you might fit well with them.

On top of this, if you meet an agent at a conference or writing-related event, mention that! Again, agents get many, many queries, so if they ask you to send them stuff, or you spoke to them, remind them where you met them, and any relevant details related to your work you might have discussed. This will hopefully set you off on the right foot and be the start of a wonderful author-agent relationship.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Personalizing a query is a great way of letting agents know that you've researched their tastes and interests, which also conveys that you're taking a professional, well-considered approach to querying and the industry itself. When you let an agent know that you've chosen them specifically because of the clients and/or books they represent, because of their online presence, or because of an interview they've given, it shows them you've taken the time to learn who they are--which also means it's likelier that you're sending them a manuscript suited to their tastes.

Salima is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Although writing queries is more an art than a science--and it can often feel like screaming into the void--if you take the time to carefully research potential agents, editors, and publishers, then your odds of approaching an appropriate one for your project (i.e., someone who would be interested in it), are far higher. Being able to demonstrate that research by being able to personalize your query will make you stand out in a good way. Conversely, if you send out copycat queries blind, you're less likely to wind up in front of someone who will resonate with whatever you're pitching. "Personalizing" includes using correct basic info (name, title, company, etc.), but also appealing to relevant aspects of the recipient's professional and personal background, from the types of books they typically represent (or what kinds of articles they publish if you're pitching mags) to whatever hobbies they may have that dovetail with what you're writing about. In other words, personalizing can't possibly hurt and might just help.

Lisa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

It’s like junk mail vs. "real" mail. When I get an envelope with an advertiser's name, I usually toss it aside, thinking I don't need a new garage floor or whatever they're selling. But when I get mail addressed to me personally from a real person, I'm much more likely to want to know what they have to say.

Barbara is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

While some advisors might suggest that one generic query letter is appropriate for all agents, my best advice is that you personalize every query you send. This means researching every agent, finding out what authors and books they have represented, and then using at least one "comp" (comparative title" / "competitive title") on that agent's (or their agency's) roster. When you do this, the agent knows that:

- you are querying them because you're familiar with their work and you know your book is a fit for them,

- your book suits their agency's roster, and

- you have done your homework.

When writing a query letter, follow the agent's submission guidelines precisely. For example, an agent named Jane Smith might request on her submissions page that she be addressed as "Ms. Jane Smith." So, if in your salutation, you write, "Dear Jane" or "Dear Ms. Smith," that is instant notification to the agent that you haven't read (or haven't followed) her submission guidelines. Will that mean you won't follow her directions if she signs with you? Agents get literally hundreds of queries every month. Don't give an agent a single reason to reject your query.

Some agents care a lot about personalized query letters, and other agents accept that some authors prefer to send out generic letters. Since you don't know which agents have which preferences, it makes sense to personalize all your query letters.

Happy querying!

Michael is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In my experience, personalizing a query letter shows a few things:

- Your interest in working with that particular agent. This increases their interest in your project and your agent-author relationship.

- Your knowledge of the market and targeted marketing. As a writer you don’t need to be a pro at this, but showing your ability to promote yourself displays valuable skills that can be used later for things like author events.

- Your research skills. Showing that you are good at finding the right agent showcases your research skills which may come in handy for your work, particularly if it’s nonfiction.

Hope this helps!

Samantha is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

It shows you've done the hard work of doing research and aren't submitting to just anybody. It adds a personal touch and hopefully will make you stand out from the rest of the crowd. If you can reference a book or two represented by the agent, and compare it to the book you have written, you will bolster your argument for approaching this particular agent. This research takes time, but I believe that, in the end, it can make a difference in helping your query stand out.

Ken is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You’ve got the agents to query and a great letter. Time to get pitching.

4. Sign a literary agent

With your polished query letter in hand, open that spreadsheet of vetted agents and begin submitting according to each one’s guidelines.

There are different strategies for sending queries. Some authors prefer to blast out queries to 50-60 agents at once to compress the long waiting periods, while others send smaller waves (for example, three batches of 20) to gauge feedback and potentially refine their query letter between rounds.

Q: What are the main reasons major publishers don't accept direct submissions from authors, and how can authors successfully navigate the submission process?

Suggested answer

It's about time and workload. The in-house editors simply don't have time to read the many, many submissions they would get as well as taking care of the editorial, admin, and other work that they're responsible for. So agents that they connect with get to know the acquiring editors' preferences and tastes, and send them books they're most likely to love. The agents act as a filter. And it's still A LOT of reading to find those outstanding books that the editor knows they can shape with the author, champion in-house, and sell to the world!

Margot is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In short, volume. Literary agents receive hundreds, if not thousands, of queries a month. Editors, who are paid by publishing corporations, have jobs not only editing the books scheduled to publish every year, but they also have to liaise with production departments (the folks who work to turn a manuscript into a physical book), marketing and publicity teams, finance, art departments, etc.

And even with literary agents acting as a sort of "filter", editors still receive hundreds of potential books sent to them every year.

Literary agents also work for authors. Earlier, I mentioned that editors are paid by the companies they work for, that is publishers. Inherent in that dynamic, editors are paid to help find and bring books to the market that will make money for the company they work for. That means if there's a disagreement on what should happen with a specific book where the publishing company is on one side and the author is on the other, then the editor is biased (or at the very least can be pressured and influenced) to agree with the company paying them, not the author they're working with.

Literary agents fill that gap as publishing professionals who are author advocates. As an extension of having an entire role dedicated to author care, it makes sense to include working with authors at the earlier stages of writing a book, too.

Matt is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Track every submission date, query status, and feedback in a single sheet so nothing slips through the cracks.

This stage will test your patience. Some writers land representation in weeks; others spend years in the so-called “query trenches.” If an agent’s stated response window passes, send a polite nudge — usually a brief “just checking in” email. If one agent requests the full manuscript, alert the others you’ve queried; a little competitive pressure can speed up reads.

Learn to handle rejection (and radio silence)

When querying, rejection is inevitable — sometimes in the form of a courteous pass, sometimes via silence. Take each “no” as data, not a verdict on your talent. Maybe you still need to improve your book’s content or pitch. Or perhaps it would be prudent to start drafting your next book, rather than endlessly polish a project that isn’t gaining any traction.

Q: When is it appropriate for authors to follow up on query letters, and how long should they wait before doing so?

Suggested answer

Check with the agency's or agent's guidelines on this; often, there will be something on the website or on the query form that will say something like, "If you don't hear back within X weeks, consider it a pass" or even, "Please wait X weeks before following up." Always follow the guidelines.

Unfortunately, it can take a long time to hear back--there are many more authors out there than there are industry professionals, and there just isn't as much time to dedicate to queries as we would like (it's also unpaid time). Most agents won't mind receiving a nudge, but I recommend waiting at least 3 months/12 weeks before doing so (unless they specify otherwise on their website). Keep it short and friendly and professional as possible. If they specify on their website not to nudge, please be respectful and don't nudge.

An exception would be if you have received an offer of rep or an offer to publish by an indie press. If that's the case, congratulations! Typically, you would contact any agent that still has your query (especially if they have requested pages) and give them a timeframe (usually about 10 days to 2 weeks) to get back to you by. (Please do not nudge with an offer of representation if you have not actually received an offer, though.) That way, they have the chance to prioritize your manuscript and counter with an offer, if they love it enough.

Sadly, if you don't hear back in another few weeks after a nudge, it's likely a pass, and I don't recommend nudging again.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Many debut deals come from a writer’s second or third manuscript. Each new endeavor sharpens your craft. Learn to separate your self-worth from the outcome: celebrate each query sent and every bit of constructive feedback received, then keep moving forward.

😌 For inspiration, listen to this Reedsy Live with NYT bestselling author Caroline Levitt, who persisted through multiple rejections, had a publisher go out of business, and was even dropped on contract for her ninth book before finding immense success with a smaller, dedicated publisher.

Choose one for the long haul

Now, let’s assume you do get one or more agents interested in your work. You’ll probably schedule a call to discuss your book and how they envision the path to its publication. Use this time to weigh up their editorial vision, communication style, and agency reach. A seasoned agent with bestseller clout might be more appealing, but perhaps you prefer working with a newer agent with a lighter list who could offer more hands-on attention.

Q: What does a normal work day/week look like for a literary agent?

Suggested answer

I have worked with several agents. They have a lot to read as they are reading work [completed manuscripts] from their existing clients and fielding query letters from potential clients.

They may also have lunch engagements or other meetings with potential publishing houses for books they are trying to place for their current clients.

Their workload depends on the current number of clients they represent. If they are a new agent with only about 25 clients so far, that means they are looking to add many more clients. Sending a query letter to a newer agent can be a great way to land an agent because an established agent may only be looking for 2-3 new clients per year, since they are already representing a large number of authors already.

Their workload is generally heavy, so patience is key when communicating. Following up on a query letter is fine, but give them a month or so to get to it, and don't "nudge" too often.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I’m not a literary agent, but the agent who represents me as an author has become a good friend over the past twenty-plus years we’ve known each other. Her days are hectic to say the least. First, she maintains communications with her authors, their editors and publishers, her other contacts in the industry, and new authors she might want to work with. She strategizes finding the best fit for each manuscript she takes on and sends them to publishers for consideration. She keeps meticulous records, negotiates and approves contracts, reads and provides editorial advice on manuscripts, and keeps abreast on industry trends and developments. She might also handle rights other than print and digital rights, such as foreign rights, audio rights, and film rights. All this is in addition to the day-to-day management of a demanding business.

It’s no wonder literary agents sometimes have long response times to submissions. They must fit reading new manuscripts in between all the other tasks that fill their days. Because of time constraints, many agents now employ and empower “readers” to sort through the numerous submissions they receive each day. Readers may be interns, in-house editors, or aspiring agents, and most read only the first chapter or two of a submission and then decide whether to send the book onto the agent. That’s why I advise my editing clients that their openings must be as polished and close to perfectly executed as possible, so their work makes it past that initial screening.

Bottom line: Agents are very busy professionals who may be hard to reach, but if your goal is a traditional publishing deal with a major publisher, your best chance will come if you have secured literary agent representation.

Ann howard is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Also, think long-term partnership: can you see yourself collaborating over several books and years? Sign with someone who you respect and trust to represent your work for the long haul.

Work with your agent to pitch your book

Signing with an agent is a big milestone, but it doesn’t guarantee publication (sigh!). Most agents will still ask for at least one more round of revisions to make sure your manuscript is market-ready. Tackle the edits that strengthen your book, but if it feels like the changes are warping your work into something unrecognizable, it may be a sign that this agent isn’t the right fit.

Once you’re both happy with the state of your manuscript, it's up to your agent to go out in the wilderness, pitch your book to publishers, and negotiate the best possible terms for your book sales! Your job now is to sit back and let them handle the outreach.

With a bit of luck, you'll start to hear interest from editors…

5. Sign a book publishing deal

After what might feel like an eternity of waiting, the moment you've been dreaming of finally arrives: a publisher wants your book! Whether it's one offer or multiple publishers battling it out in an auction, this is when things get real — and when you'll be especially grateful to have an agent in your corner.

Evaluate the offers you receive

Not all publishing deals are equal — the best offer isn’t always the biggest advance. Consider who’s making the offer and what it means for your book’s future.

Q: Assuming a book deal, how long can an author assume the process will take from querying to seeing their book on the shelf?

Suggested answer

Having been an acquisitions editor for a division of Random House, I can tell you publishing is a marathon, not a sprint. On average, the journey from query to bookstore shelves is about two years. That might sound like forever, but every step along the way has its own milestone worth celebrating.

Here’s what it looks like:

- A Spark. An editor loves your query! Cue the happy dance. They’ll ask for more—maybe a full proposal, sample chapters, or even the whole manuscript if it’s fiction.

- The Back-and-Forth. This is the “let’s make it even better” stage. You might be asked for clarifications or revisions before your project goes to the publication board. Think of it as a friendly brainstorming session with high stakes.

- The Green Light! Once the pub board approves, a contract is drawn up. Negotiations and signatures can take 2–3 months. Then it's official and you can make announcements in public.

- The Writing Zone. You’ll usually get around six months to deliver your manuscript. This is when the real writing (or rewriting) magic happens.

- The Editorial Polish. Once you submit your manuscript, your editor helps refine your work. Developmental edits, line edits, copyedits… it’s like giving your manuscript a deep massage. This adds another 2–3 months.

- The Final Stretch. Your book is typeset, proofread, and sent to print. Depending on where it’s printed, this can take another couple of months.

- Meanwhile, the sales and marketing teams are busy building buzz, and you are stirring up excitement with pre-sales posts.

So yes—it’s a two-year adventure. But the good news? That “long runway” gives publishers time to rally booksellers, reviewers, and readers, so when your book finally launches, it’s not just quietly slipping onto a shelf or into the Amazon masses, it’s arriving with fanfare. Publishing is a process of patience, persistence, and plenty of celebratory moments along the way.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Querying is the first step of a journey through traditional publishing. After you've sent out your queries, the next steps might look something like this:

- Full requests: Literary agents who are interested in your query will request the full manuscript from you so they can read the whole book and decide whether to offer representation.

- Offer of representation: After reading your book, the literary agent has decided they would like to represent you and take you on as a client, so they send you an offer of representation. This is a good time to follow up with any other pending queries and let them know that you've received an offer of representation. Generally, you should give other agents 2 weeks to get back to you after you've let them know you've received a competing offer of representation.

- Submissions: Once you've signed with a literary agent, your agent goes out with your manuscript on submission. This might happen right away (if your agent believes your manuscript is ready) or after a round or two of revisions. The amount of time this might take varies greatly.

- Editor interest: Editors who are interested in your book may have to drum up internal support at their publishing house before they can make an offer. This could look like the editor bringing the project to their editorial meeting, then presenting it at an acquisitions meeting. This could take up to 2 weeks depending on the process at that particular publishing house. You may have a call with the editor as well to make sure your visions are compatible.

- Book deal offer: Your prospective editor will send an offer to your agent, and they will negotiate.

- Editing begins: Once you've come to an agreement on the book deal, you will begin working with your editor. All in all, it generally takes about 2 years between a book deal and the book's publication date. This looks like about 1 year of editing and revising, and then 6 months of the book moving through different stages of production, and then it goes out to the printer, is physically produced, and ships to distributors, who then sell to booksellers, who then stock the book.

Of course, the timelines for the items I've listed here vary greatly. But generally speaking, it's safe to assume at least 2 years between book deal and publication...plus the amount of time you've had between querying and getting that book deal. This is part of the reason I encourage authors not to chase trends and instead to focus on writing compelling characters—traditional publishing is slow, so write from the heart. Strong character work and a good command of craft will appeal regardless of the shifting trend cycles.

Christine is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Allow a publisher's editorial board 30 - 60 days to finalize an offer and negotiate details. After that, expect 8 to 16 months before your cover sees the light of day. Why so long? Legitimate publishers allocate marketing and trade sales resources on their calendar. They also sometime like to schedule titles based on best selling seasons for a particular genre.

Mike is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Big Five publishers typically offer larger advances and wide distribution, but may move on quickly if a book underperforms. Indie and digital-first publishers often offer smaller advances but more personal attention, higher royalties, and creative input. That kind of focused support can lead to faster earn-outs and lasting career momentum — many authors, like Gina Sorell, started with a small press and later moved to a Big Five publisher.

As you did on your quest for an agent, you should weigh the publisher’s vision, track record, and alignment with your long-term goals. Ask your agent to help assess the fit.

Consider the contract

Publishing contracts are dense documents full of legalese that would make most writers' eyes glaze over — which is exactly why your agent earns their 15% commission. They'll handle the heavy lifting, but understanding the basics will help you make informed decisions.

The advance, which is a check paid upfront, is probably what you're most curious about (no judgment — we all have bills to pay). Despite the dizzying 7-figure deals you sometimes see, the reality is usually more modest — advances can range anywhere from $2,000 from small presses to $50,000 or more with the Big 5.

Q: What qualities and practices make a literary agent effective for their authors?

Suggested answer

Honesty.

I suppose that's a quality that's necessary for any job, right?

I used to be a literary agent (part-time, in addition to ghostwriting and editing). So here's why honesty is crucial.

A good literary agent must be forthright, and constructive, in delivering bad news and harsh realities.

As an author, you want an ally who will assess strengths and weaknesses head on, so they can be addressed in a book proposal, and through all the crucial steps to help you grow your brand and audience.

Mike is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Royalties are where things get interesting. Standard rates typically look like:

- 10% on hardcover sales

- 7.5% on paperback sales

- 25% on ebook sales

Many contracts include escalation clauses: hit certain sales milestones, and your royalty rate increases. But here's the catch: you won't see a penny in royalties until you've "earned out" your advance. If you received $30,000 upfront, your book needs to generate $30,000 in royalties before additional payments kick in.

Subsidiary rights are the hidden gems of publishing contracts. These cover everything beyond the standard book formats:

- Audio rights (increasingly valuable in our podcast-obsessed world)

- Foreign translation rights (your book could be a bestseller in Denmark!)

- Film and TV rights (Netflix, anyone?)

- Merchandising rights (rare, but imagine your character on a coffee mug)

Your agent will fight to retain as many of these rights as possible, or at least ensure you get a favorable split if the publisher keeps them.

There are a few other clauses that your agent will need to sort out, and the negotiation process might take weeks as your agent pushes for better terms. When the dust settles and you're holding that final contract, take a moment to celebrate. You're about to become a traditionally published author!

But don’t overdo it. You’ll still need to work on your book…

6. Refine the book with the publisher’s team

That's right. Despite editing your book with beta readers, professional editors, and your literary agent, you will have to go through at least one round of edits based on the editorial feedback you will receive from their assigned editor at your publisher.

Q: How do you adapt your editing approach to different genres and client expectations?

Suggested answer

Re. client expectations, before the work, practical goals need to be established.

I spend a lot of time with clients before offering bids, a lot of time. Call this free consultation if you wish, but since most of my clients don't know that they're about to step into the deep end of the pool, I think it's only fair that I warn them about the depth, as well as the shark infestation.

Dealing with different genres is a completely different issue.

Now, whether the book is humorous, horror, fantasy, adventure, sf, romantic comedy, or a mashup of two or more, I work with my clients to establish practical publishing goals (finding a publisher or self-publishing), and that sets the yardsticks for me to determine whether or not they measure up.

I'm personally comfortable with each of the genres I noted above, but if a client came to me with a genre-bending bodice-ripping romance, I'm probably not the right guy for the job.

Lee is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I work on picture books, novels, memoirs, and non-fiction, so I have a lot of different approaches in my pocket, ha. For picture books, it is much easier to do multiple rounds of edits, and most of my clients choose a multi-round package. That means I move from overall feedback down to line notes as the project progresses. I try to take a similar approach to longer projects, though I don't always get to see more than one draft. I'll often include taking a second look at a short excerpt--normally the beginning--in my editing package.

In term of client expectations, if I've done my job well, these will be clear before we even start working. I am constantly tweaking the language in my sales messages and offers to clarify issues that have come up with clients in the past. I am fairly flexible in changing my approach depending on how the client likes to work. For example, one client of mine prefers to talk through all of the changes in her picture book on the phone. That's pretty rare these days, but it works great for her, and we have a lot of fun on our phone calls!

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Each genre has an expectation from readers, so I edit according to the target audience and what they will expect based on the genre, title, and type of book, whether it is for children or adults, non-fiction or fiction.

Non-fiction readers of self-help, for instance, are looking to grow and learn. So I will edit this type of book for clarity, pacing, and whether or not it provides new information for readers that they are eager to learn. These types of books must also have strong takeaways and practical applications, since readers expect this from this genre.

A historical novel, a fantasy novel, or a sci-fi novel will need to allow for strong world-building. This is needed more so than in a novel that takes place in the present day.

So, having experience editing these types of books and keeping reader expectations in mind is what is needed here.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I find it really helpful to get a good sense of where the author wants their book to sit within the existing market. I like to ask them about who their target reader is, and what other books their target reader enjoys reading. Knowing that an author wants their thriller, for example, to sit on the more literary side of the market can really help guide my edits, and I can explain why I have made certain suggestions. Sometimes the process works differently, and I'll recommend a range of books I think the reader might find helpful to read, and they can tell me where they'd ideally like their book to 'sit' within that range.

Thalia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This is done in two ways, I think. The first is doing an adequate assessment of the manuscript to determine what edit the manuscript needs and what level: heavy line edit? Light developmental edit? Copy edit? Second, it's important to be clear in your offer to the writer about what your editorial plan is. A copy edit, for example, will include ensuring accuracy, consistency, completeness, and correctness, in accordance with Editors Canada's standards. If these terms are outlined in your offer, and your offer is based on some careful thinking about the manuscript's needs, it should be easy to meet the expectations since you set them yourself!

An important asterisk to this I suppose is making sure there is good professional chemistry between editor and writer. Hold a virtual meeting; get to know each other, if only briefly. It's worth it to put in this extra (yes, unpaid) time.

Holly is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Your acquiring editor will send you an editorial letter to improve your book further. Fiction writers might need to flesh out scenes or rethink plot points, while nonfiction authors who sold on a proposal will need to deliver those final remaining chapters. Either way, expect at least one substantial revision, possibly more.

The production marathon begins

Once you and your editor agree the manuscript is ready, your book enters the production pipeline — and things move fast.

- Cover design: You'll provide input on design concepts, but the publisher has final say. Speak up quickly if you hate the initial options!

- Marketing and publicity: You'll collaborate with these teams to identify target audiences, potential blurbers, and promotional angles for your book.

- Copy editing: A professional will meticulously review your manuscript line-by-line, catching everything from grammar errors to plot inconsistencies.

- Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs): These early, unpolished versions of your book go out to reviewers and booksellers 3-6 months before publication — seeing your book in print for the first time is unforgettable.

- Proofreading: Both you and a professional proofreader get one final chance to catch any lingering errors before your book goes to print.

Throughout this process, deadlines will feel relentless, and you'll wonder how any book ever makes it to shelves without any errors. But trust the process, and the talented team working to make your book shine. Before you know it, you'll be holding the finished product, ready to share your story with the world.

7. Celebrate your book’s launch

When your author copies arrive about a month before publication, do that happy dance and drink that Champagne. It’s quite a magical feeling, and you've certainly earned it!

Done? Okay, now it’s time to roll up your sleeves: the promotion phase begins. Most authors today shoulder much of their own promotion, regardless of advance size.

Q: How do marketers tailor a book marketing plan to an individual author’s goals and genre?

Suggested answer

It really depends on what the author wants to achieve. Some people just want to cross “publish a book” off their bucket list—and that’s great! For them, we keep things simple and practical. The focus is on getting their book out there without making it overly complicated.

For authors who want to build a career, though, the strategy looks very different. We think about the big picture: Who’s your ideal reader? What’s the plan for future books? How can you keep readers engaged and excited? It might mean building an email list, planning a multi-book launch strategy, or figuring out how to market consistently over time.