Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 28, 2022

Third Person Omniscient: Bird's Eye View Narratives

Third person omniscient point of view is a narrative technique that provides a panoramic and all-knowing perspective in a story. By allowing readers to access the thoughts, emotions, and experiences of multiple characters in a story, it's considered one of the most flexible but challenging POVs for authors to use.

Third person omniscient is perhaps the oldest narrative form of recorded storytelling, used by our ancestors to tell the tales of Odin, Heracles, and Amun-Ra. Let’s look at why storytellers across time love it so much, and what makes this point of view so powerful.

Omniscient narrators can read the characters’ thoughts

As they already know what each character is thinking and feeling at all times, an omniscient narrator gives authors the unique opportunity to examine many characters’ psyches at once. The narrator can also know things about the characters they aren’t aware of yet – or would be willing to divulge if they were the ones telling the story.

In this passage from Annie Proulx’s short story "Brokeback Mountain," we are privy to two separate, private moments of longing.

During the day Ennis looked across a great gulf and sometimes saw Jack, a small dot moving across a high meadow, as an insect moves across a tablecloth; Jack, in his dark camp, saw Ennis as night fire, a red spark on the huge dark mass of mountain.

— "Brokeback Mountain", Anne Proulx

Unbeknownst to each other, both Ennis and Jack look for each other during the day, demonstrating how they are present in each other’s thoughts. The images playing in their heads are a great reflection of their character. Ennis’s thoughts are simpler, imagining ants on a tablecloth, while Jack’s are grander and more romantic, conjuring up fire and sparks in the night. With this brilliant example of show, don’t tell, we can see the strength of their connection in its quietest, most private expressions. This particular moment would be impossible to describe with a limited viewpoint.

As well as knowing what every character knows, the omniscient narrator is privy to all things that they don’t know — information that can be shared with the reader at critical moments to great effect.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

All-seeing narrators can summon suspense from thin air

An omniscient narrator knows more about the events of the story than the main characters do, so they can be used to create tension and dramatic irony. That is where the reader knows something that the main characters do not. Sometimes, this irony is used for humorous effect but more often, we’ll see it as a device for ratcheting up the suspense.

For example, in Seishi Yokomizo’s mystery novel The Inugami Curse, a wealthy family awaits their patriarch’s death to see who will inherit his fortune. But, as the narrator reveals, they have no way of knowing, as they sit at his deathbed, what tragedies await them.

That was the end of the life of Sahei Inugami – the end of his eighty-one turbulent years. In hindsight, we now know that his death set in motion the blood-soaked series of events that later befell the Inugami clan.

— The Inugami Curse, Seishi Yokomizo

The omniscient narrator tells the readers, with a wink and a nudge, what to expect as the story unfolds. But at this moment, the characters remain clueless about the murders and intrigue that will come as they fight for control of Sahei Inugami’s will. Thus, a sense of tension and dread is conjured — something perfectly suited to a detective novel.

Although omniscient narrators take a god’s eye view of the story, that doesn’t mean they have to be cold, detached figures.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

The narrator can become a character in their own right

Conventionally, omniscient narrators don’t appear in a story, though they are still characters in a sense. Sometimes, they remain out of the way and don't draw attention to themselves. Very often, though, they will have a distinct personality or worldview that they add to the story.

From this section of Middlemarch by George Eliot, we learn a little about how the narrator views some of the inhabitants of the town.

The troublesome ones in a family are usually either the wits or the idiots. Jonah was the wit among the Featherstones, and joked with the maid-servants when they came about the hearth, but seemed to consider Miss Garth a suspicious character, and followed her with cold eyes.

— Middlemarch, George Eliot

Middlemarch’s subtitle, “A Study in Provincial Life,” allows the reader to imagine that the narrator is some sort of academic. In describing the town’s citizens, they take an almost sociological view that puts the reader in mind of a middle-class inhabitant of the community making pithy observations about their neighbors and how they act. They invite the reader to see the good people of Middlemarch through their perspective and analysis.

More than just distinct individuals with distinct opinions on the characters, omniscient narrators might occasionally wish to appeal directly to the reader.

FREE COURSE

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

Omniscient narrators can offer lessons or opinions

Just as omniscient narrators have personalities, they can also express their own thoughts and feelings. While bound by their own limitations as passive observers, they might have something to say about the story they’re telling. Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief is narrated by Death himself, a character who watches over humanity. While he only plays a small role in the lives of the protagonists, he has much to say about what he witnesses and wants the reader to learn from it, like he has.

Another example of an omniscient narrator with a strong worldview can be found in George Gissing's The Nether World. Gissing exposes the lives of the poor in Victorian London and concerns itself with showing all the hardships experienced by the lower classes. The novel’s (and the narrator’s) views are incredibly pessimistic and, for its time, controversial.

Society produces many a monster, but the mass of those whom, after creating them, it pronounces bad are merely bad from the conventional point of view; they are guilty of weaknesses, not of crimes.

— The Nether World, George Gissing

This passage is the novel’s thesis statement, an idea that the narrator strives to convince the reader of. It’s an assertion that serves as the underpinning for the story being told. However, taking this approach has certain dangers, especially when the subject matter is so closely related to problems of the real world. If your omniscient narrator has a specific worldview and isn’t established as a character in the story, readers will likely assume these opinions are yours 一so, take care if you’re writing ironically about sensitive topics.

Would you see how what this potent POV looks like in practice?

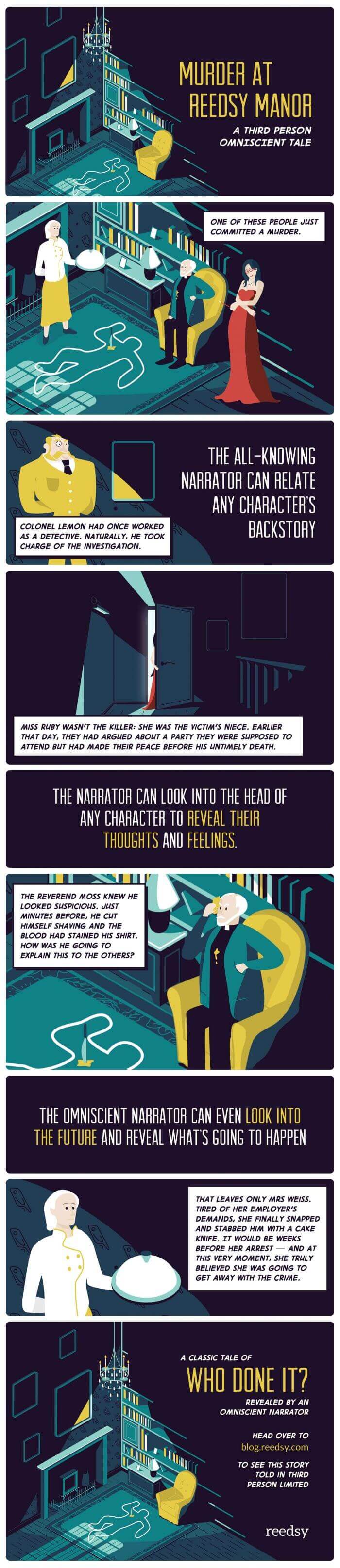

Omniscient Example: Murder at Reedsy Manor

In our previous post on the third person limited point of view, we shared a comic strip showing that particular viewpoint in action. To round out this post on omniscient narrators, let us return to that fateful evening at Reedsy Manor.

Now that we're all caught up with third-person viewpoints, let's learn more about a unique yet underused narrative perspective: fourth person POV.

11 responses

Jennie says:

15/05/2019 – 22:45

I have been using an omniscient third person POV because that’s what I enjoy reading, I suppose, and because it lets me impart the information I want to impart. I’ve just received some feedback that I should tighten that perspective—code for limiting the POV, I suppose—and now I’m on the fence. The constant tension between making the art that I believe in and making the art that might get published and thus have the chance to be seen is distracting, compounded by the conflicting messages of lit mag publishers, “Be brave! Be bold! Be new! But please do it within these narrow confines dictated by current fashion.” Sigh...

↪️ Raya Moon replied:

31/10/2019 – 13:16

I love that last comment. It definitely seems to be the case which makes getting published that much harder. Maybe that's why I dread ever starting the process.

↪️ Khan Wong replied:

30/01/2020 – 04:35

In the same boat!

Tiffany says:

12/07/2019 – 19:50

Say I’m writing a novel in third person and i only sometimes needed someone else’s POV, but only rarely, would i use Multiple third person limited or omniscient? Or would it be better to write in first person POV and separate those chapters/moments it’s writing their name in bold lettering to separate it like Stephanie Meyers did in Breaking Dawn? Like i only need the other POV once or twice in the whole series I’m writing.

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

16/07/2019 – 08:47

In cases like this, the key is to let the reader know as soon as possible that they're not following the same POV character. You might do that with chapter headings as you say, but you can also heavily suggest it with the language. If it's in the first person, use the "I" pronoun quite heavily at the start of the chapter and the reader will immediately wonder whose POV this is... then as soon as they figure it out, it'll all click for them. Then the next time you switch back to First Person mode, their assumption is that it will be the same character.

JoML says:

08/08/2019 – 05:45

I've just joined a writers group and have been told I'm switching POV in a short story. The founder says in one of her articles that third person POV should be written in that character's style of speech, thought etc. It got me wondering, what happens to the actual narrator in third person limited? Eg I start with a bird's eye view of the ocean, surfers etc and zoom in to one single surfer, who is the main character. I'm not going to write that first scene in her voice. That seems ridiculous. Is there a possibility that writers can become so fixated on this that they forget there's always a narrator, no matter how invisible? I also want the reader to see this girl through the father's eyes at one point, but I'm being forced to edit this out unless I commit to third person omniscient. I've been writing for a long time and only just learning the technicalities, so could have got this all wrong.

↪️ Yvonne replied:

10/08/2019 – 04:17

Your writer's group may be correct here. Third person limited is restricted to one character's thoughts and feelings. A third person omniscient narrator is the only narrator who can "see" everything and access everyone's perspectives at any given point in time — so yes, in your example of a father and his daughter, it sounds like you're exercising the use of a third person omniscient narrator. (That said, multiple third person limited POV is an option, as we mentioned above.) This post with 70+ examples of POV may be useful in helping you distinguish between each of them: https://blog.reedsy.com/guide/point-of-view/. And if you'd like more clarification, feel free to email service@reedsy.com to discuss further! :)

Na says:

01/09/2019 – 00:14

Thankyou. A very informative post and I’ve been guilty of accidentally head hopping in one chapter while moving to a Martinesque multiple 3plo after this chapter. Back to the drawing board it is then for some edits...

Raya Moon says:

31/10/2019 – 13:14

I've mostly used First Person until recently, hence me looking up this article. Thanks to this I understand very vividly where i went wrong in my recent work. Mostly the head hopping issue. I wasn't sure where to go with the POV so it ended up being something of both omniscient and limited at the same time, which if it would ever be taken seriously, might be kind of funny to see work out. I liked how it was working, but others seemed thrown by it. Guess I should rectify it some. I might do two, one with each and see which way works better, but I think I will probably stick to limited, being it's closer to what I am familiar with. If anyone has seen both in a story and thinks it could work, let me know.

Cererean says:

18/01/2020 – 15:48

Given that Pratchett, Adams, and Snicket used (and in the latter case, uses) third person omniscient, it can't have been that long ago that publishers got funny about it...

Sasha Anderson says:

31/05/2020 – 11:41

I still don't really understand what "head-hopping" is. On various different advice sites, I've seen the phrase refer to anything from "having more than one person's point of view in a chapter" to "switching point of view in a way that's jarring to the reader".I can see that in a third person limited perspective, you don't want to throw in a random sentence from someone else's point of view, but in the section on omniscient point of view you say "Within a given scene, avoid filtering the action through more than one character." If you're only changing viewpoint at a scene break, isn't that just third person limited with multiple viewpoint characters? I thought the point of omniscient was that you could be in any character's head you want, as long as you do it in a way that works for the reader.Guess I still have lots to learn...