Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Aug 31, 2022

Dramatic Irony: 7 Examples of Suspenseful Ignorance

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Dramatic irony is a plot device used in literature, in which the audience is aware of information that the characters are not. It usually takes the form of the characters being unaware of an impending tragedy or misfortune.

Though it’s most often associated with classical and Shakespearean tragedy (and is sometimes called tragic irony for that reason), dramatic irony appears in many different genres, and doesn’t exclusively lead to disaster. As the spectrum of genres examined below will show you, this type of irony can bring readers closer to fictional characters, wreak devastation or misunderstanding, and create powerful dynamics between characters whose levels of awareness differ.

Regardless of genre, dramatic irony can make any story more impactful — so let’s look at some examples.

Romeo’s reaction to finding ‘dead’ Juliet

Toward the end of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Romeo hears that Juliet has died and rushes to her tomb to see her. Upon seeing her, he admires her beauty: “Death hath had no power yet upon thy beauty.” Of course, this is for good reason; Juliet isn’t actually dead. The audience knows this, though Romeo doesn’t — and he tragically decides to commit suicide.

The audience, rooting for this star-crossed couple, is devastated by the meaninglessness of his death — and so the play enters the ‘return’ stage of Freytag’s pyramid, where it quickly spirals toward catastrophe.

Romeo thinks only of joining his beloved; the audience can only think of what it’ll be like for Juliet to wake up to her lover dead at her side. This classic example of dramatic irony is extremely effective, because it makes the audience want to reach their hands into the play and stop Romeo, to tell him not to kill himself in vain, but of course they cannot do that. Stuck with the knowledge of Romeo’s misguided decision, the audience can only watch helplessly as fate takes its course.

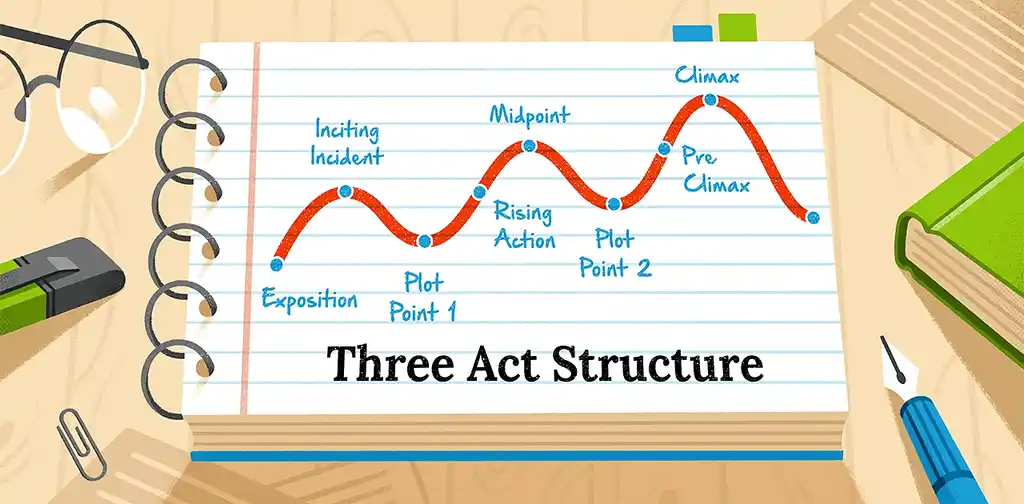

Want to learn more about how story structure operates? Just sign up to our free course below:

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

Racist microaggressions unnoticed by most in Real Life

You can take a group of people and put them in a room, and they’ll all experience the same evening differently. Each one’s personality and prior experiences have a direct impact on the way they perceive the world. For people belonging to minority groups, their very identity leads to them noticing comments and behavior motivated by prejudice or ignorance that other people may not think twice about.

In Brandon Taylor’s literary fiction novel Real Life, Wallace, the protagonist, attends a party where he’s subjected to a series of racist microaggressions. Other people don’t react, respond, or bat an eyelid — but the reader, seeing things through Wallace’s eyes via a limited third person point of view, understands that there are many layers of experience at play in this scene.

Through dramatic irony, Taylor manages to portray the sense of alienation someone can feel when surrounded by a group oblivious to its own prejudices, and being the only one to recognise this undercurrent of ignorance. In this case, dramatic irony creates a devastating sense of solitude and isolation, as both protagonist and reader fear that the oblivious group will never know just how much they aren’t seeing.

📚Looking for your next read? Head to our list of 70 must-read books by Black authors.

Oedipus’ self-destructing pledge

In Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Oedipus, king of Ancient Thebes, pledges to investigate who murdered the last king. What he doesn’t know is that the king, Laius, was the old man he encountered and killed in a fight outside Thebes — so the play begins with Oedipus unwittingly taking an oath to seek himself out, and punish himself.

You can already picture the audience holding their heads in their hands while listening to the ominous oath Oedipus takes. Now add to that the fact that Oedipus has received a prophecy from an oracle stating he was destined to kill his own father and end up marrying his own mother… Do you not already feel the power of dramatic irony in this play?

Filled with dread and fear on Oedipus’ behalf, the audience is forced to watch him actively seek out his own undoing.

Benson and Mike’s long-distance relationship in Memorial

Bryan Washington’s Memorial is a romance lit fic novel told from two different points of view (both characters, Japanese-American Mike and African-American Benson, speak in first person). The book begins with Mike deciding to visit his dying father in Japan, as his Japanese mother arrives to visit him in America. Effectively, Mike leaves his boyfriend and mother to share a flat, when they’ve never even met — an utterly bizarre experience for both of them.

Bryan Washington’s Memorial is a romance lit fic novel told from two different points of view (both characters, Japanese-American Mike and African-American Benson, speak in first person). The book begins with Mike deciding to visit his dying father in Japan, as his Japanese mother arrives to visit him in America. Effectively, Mike leaves his boyfriend and mother to share a flat, when they’ve never even met — an utterly bizarre experience for both of them.

While Mike and Benson are geographically apart, their relationship is under tension: they begin to wonder who they really are, whether they fit together, and whether the core of their relationship will be strong enough to endure the distance.

In this book, dramatic irony is born out of their state of separation, not out of a particular fact one of them is ignorant of. Instead, there is a steady accumulation of thoughts and incidents in the daily life of each that the other does not get to witness, making the silence between them graver, and more difficult to break.

This form of dramatic irony introduces an element of tragedy by highlighting the helplessness with which the two men have to face the distance between them — though (spoiler alert) it happily doesn’t lead to catastrophe.

Plotting across Westeros in A Song of Ice and Fire

One of the most compelling elements of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, and something the Game of Thrones TV series got absolutely right, is the narrative’s epic sense of scale. Written in third person point of view, these books rotate between characters with every chapter, showing continuous developments on multiple fronts. Arya Stark, on a far-off continent, plans revenge. In the Castle Keep at King’s Landing, Cersei Lannister forges alliances and seeks to cement her family’s position of power. Atop the Wall, the Night’s Watch witnesses the rise of an undead enemy. Crossing the sea, Daenerys Targaryen sails toward Westeros in hopes of claiming the throne as her birthright.

The reader sees the moves made by multiple warring factions, and watches them slowly creep closer toward war, without the characters themselves being aware of everything that’s happening elsewhere. Here, dramatic irony affords the reader a bird’s eye view of everything going on, heightening tension and increasing the stakes of the story — ensuring, in other words, that the reader will stay hooked as the plot unfolds.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

The hidden, scheming villain of Gecko Chan

In the children’s webcomic series Gecko Chan by Meritxell Garcia, the adorable character of the same name has a lot of questions about where they really come from, and how they ended up being adopted by human parents. As Gecko struggles to fit in at a human school and begins to learn a little more about their past, the reader has access to a parallel storyline where R-obin, a purple-haired engineering mastermind, is working on a technology that can help her track Gecko down.

Gecko doesn’t know R-obin exists and is on the prowl, let alone that she’s building smart tech that can detect Gecko’s screams. The reader does, though, and Gecko’s haplessness adds to the suspense of the webcomic, getting young readers invested in the adorable protagonist’s safety and giving the narrative a driving force long before R-obin and Gecko even meet. In that sense, dramatic irony ends up shaping the narrative by showing a path forward.

Free course: Writing Children's Books 101

Is your book appropriate for the age of its target reader? Find out in this free online course. Get started now.

History changing the context of Anne Frank’s diary

When young Jewish girl Anne Frank was writing diary entries in 1942, she never planned for anybody else to see them. She says as much in the diary itself: “Who else but me is ever going to read these letters?” The tragedy, of course, is that the answer to this rhetorical question, once a comforting “nobody”, has since been changed by the horrible onset of history.

Anne Frank did not survive the Holocaust, but her diary did, and though she didn’t know it at the time, it would go on to be read by millions and millions of people. Contemporary readers will be heartbroken to encounter the above question — because it shows faith in things turning out well, and we all know that they did not, and that humanity failed Anne Frank, as well as millions of Jews and other marginalized groups.

Dramatic irony, in this case, is extratextual — it wasn’t intentionally included by Anne Frank, but it’s nonetheless the result of the diary’s context being very different for readers now than it was for her at the time of writing. Even so, the emotional impact of the diary as a historical document is made all the more acute through dramatic irony.

It’s common to mistake dramatic irony for something that only happens in Classical or Shakespearean tragedy, but the device actually appears in a far wider range of works, propelling the narrative forward and engaging the readers. Omniscience is not required for dramatic irony to be effective — just one unknown fact can really power up a story.

We hope this post has helped you understand this final type of irony well — in case you haven’t seen the other posts in this guide, we’ve also covered verbal and situational irony in separate posts. Happy reading!