Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 14, 2023

10 Types of Creative Writing (with Examples You’ll Love)

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

View profile →A lot falls under the term ‘creative writing’: poetry, short fiction, plays, novels, personal essays, and songs, to name just a few. By virtue of the creativity that characterizes it, creative writing is an extremely versatile art. So instead of defining what creative writing is, it may be easier to understand what it does by looking at examples that demonstrate the sheer range of styles and genres under its vast umbrella.

To that end, we’ve collected a non-exhaustive list of works across multiple formats that have inspired the writers here at Reedsy. With 20 different works to explore, we hope they will inspire you, too.

Poetry

People have been writing creatively for almost as long as we have been able to hold pens. Just think of long-form epic poems like The Odyssey or, later, the Cantar de Mio Cid — some of the earliest recorded writings of their kind.

Poetry is also a great place to start if you want to dip your own pen into the inkwell of creative writing. It can be as short or long as you want (you don’t have to write an epic of Homeric proportions), encourages you to build your observation skills, and often speaks from a single point of view.

Here are a few examples:

“Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This classic poem by Romantic poet Percy Shelley (also known as Mary Shelley’s husband) is all about legacy. What do we leave behind? How will we be remembered? The great king Ozymandias built himself a massive statue, proclaiming his might, but the irony is that his statue doesn’t survive the ravages of time. By framing this poem as told to him by a “traveller from an antique land,” Shelley effectively turns this into a story. Along with the careful use of juxtaposition to create irony, this poem accomplishes a lot in just a few lines.

“Trying to Raise the Dead” by Dorianne Laux

A direction. An object. My love, it needs

a place to rest. Say anything. I’m listening.

I’m ready to believe. Even lies, I don’t care.

Poetry is cherished for its ability to evoke strong emotions from the reader using very few words which is exactly what Dorianne Laux does in “Trying to Raise the Dead.” With vivid imagery that underscores the painful yearning of the narrator, she transports us to a private nighttime scene as the narrator sneaks away from a party to pray to someone they’ve lost. We ache for their loss and how badly they want their lost loved one to acknowledge them in some way. It’s truly a masterclass on how writing can be used to portray emotions.

If you find yourself inspired to try out some poetry — and maybe even get it published — check out these poetry layouts that can elevate your verse!

Song Lyrics

Poetry’s closely related cousin, song lyrics are another great way to flex your creative writing muscles. You not only have to find the perfect rhyme scheme but also match it to the rhythm of the music. This can be a great challenge for an experienced poet or the musically inclined.

To see how music can add something extra to your poetry, check out these two examples:

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen

You say I took the name in vain

I don't even know the name

But if I did, well, really, what's it to ya?

There's a blaze of light in every word

It doesn't matter which you heard

The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Metaphors are commonplace in almost every kind of creative writing, but will often take center stage in shorter works like poetry and songs. At the slightest mention, they invite the listener to bring their emotional or cultural experience to the piece, allowing the writer to express more with fewer words while also giving it a deeper meaning. If a whole song is couched in metaphor, you might even be able to find multiple meanings to it, like in Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” While Cohen’s Biblical references create a song that, on the surface, seems like it’s about a struggle with religion, the ambiguity of the lyrics has allowed it to be seen as a song about a complicated romantic relationship.

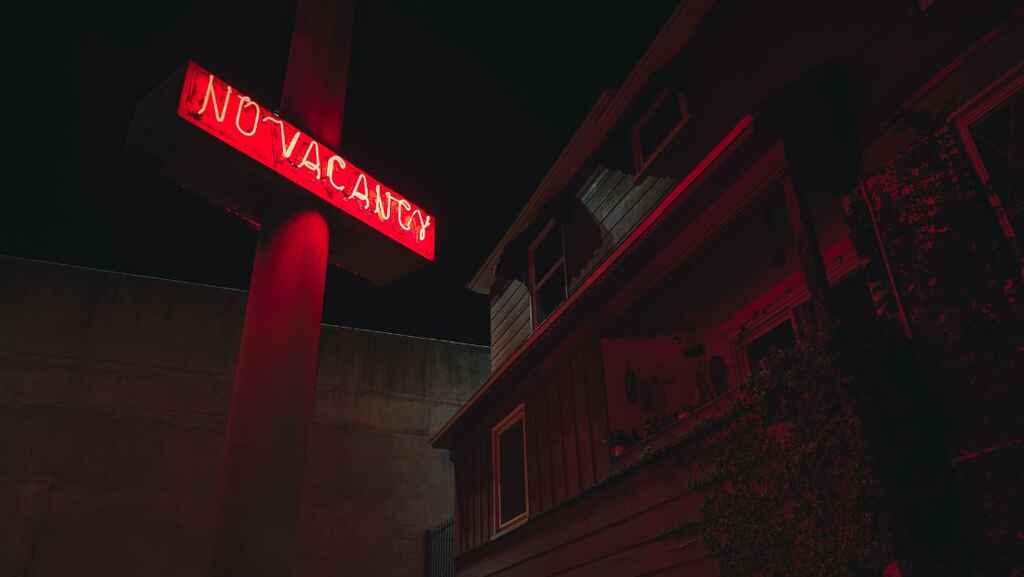

“I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie

If Heaven and Hell decide that they both are satisfied

Illuminate the no's on their vacancy signs

If there's no one beside you when your soul embarks

Then I'll follow you into the dark

You can think of song lyrics as poetry set to music. They manage to do many of the same things their literary counterparts do — including tugging on your heartstrings. Death Cab for Cutie’s incredibly popular indie rock ballad is about the singer’s deep devotion to his lover. While some might find the song a bit too dark and macabre, its melancholy tune and poignant lyrics remind us that love can endure beyond death.

Plays and Screenplays

From the short form of poetry, we move into the world of drama — also known as the play. This form is as old as the poem, stretching back to the works of ancient Greek playwrights like Sophocles, who adapted the myths of their day into dramatic form. The stage play (and the more modern screenplay) gives the words on the page a literal human voice, bringing life to a story and its characters entirely through dialogue.

Interested to see what that looks like? Take a look at these examples:

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

“I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Arthur Miller acts as a bridge between the classic and the new, creating 20th century tragedies that take place in living rooms and backyard instead of royal courts, so we had to include his breakout hit on this list. Set in the backyard of an all-American family in the summer of 1946, this tragedy manages to communicate family tensions in an unimaginable scale, building up to an intense climax reminiscent of classical drama.

💡 Read more about Arthur Miller and classical influences in our breakdown of Freytag’s pyramid.

“Everything is Fine” by Michael Schur (The Good Place)

“Well, then this system sucks. What...one in a million gets to live in paradise and everyone else is tortured for eternity? Come on! I mean, I wasn't freaking Gandhi, but I was okay. I was a medium person. I should get to spend eternity in a medium place! Like Cincinnati. Everyone who wasn't perfect but wasn't terrible should get to spend eternity in Cincinnati.”

A screenplay, especially a TV pilot, is like a mini-play, but with the extra job of convincing an audience that they want to watch a hundred more episodes of the show. Blending moral philosophy with comedy, The Good Place is a fun hang-out show set in the afterlife that asks some big questions about what it means to be good.

It follows Eleanor Shellstrop, an incredibly imperfect woman from Arizona who wakes up in ‘The Good Place’ and realizes that there’s been a cosmic mixup. Determined not to lose her place in paradise, she recruits her “soulmate,” a former ethics professor, to teach her philosophy with the hope that she can learn to be a good person and keep up her charade of being an upstanding citizen. The pilot does a superb job of setting up the stakes, the story, and the characters, while smuggling in deep philosophical ideas.

Personal essays

Our first foray into nonfiction on this list is the personal essay. As its name suggests, these stories are in some way autobiographical — concerned with the author’s life and experiences. But don’t be fooled by the realistic component. These essays can take any shape or form, from comics to diary entries to recipes and anything else you can imagine. Typically zeroing in on a single issue, they allow you to explore your life and prove that the personal can be universal.

Here are a couple of fantastic examples:

“On Selling Your First Novel After 11 Years” by Min Jin Lee (Literary Hub)

There was so much to learn and practice, but I began to see the prose in verse and the verse in prose. Patterns surfaced in poems, stories, and plays. There was music in sentences and paragraphs. I could hear the silences in a sentence. All this schooling was like getting x-ray vision and animal-like hearing.

This deeply honest personal essay by Pachinko author Min Jin Lee is an account of her eleven-year struggle to publish her first novel. Like all good writing, it is intensely focused on personal emotional details. While grounded in the specifics of the author's personal journey, it embodies an experience that is absolutely universal: that of difficulty and adversity met by eventual success.

“A Cyclist on the English Landscape” by Roff Smith (New York Times)

These images, though, aren’t meant to be about me. They’re meant to represent a cyclist on the landscape, anybody — you, perhaps.

Roff Smith’s gorgeous photo essay for the NYT is a testament to the power of creatively combining visuals with text. Here, photographs of Smith atop a bike are far from simply ornamental. They’re integral to the ruminative mood of the essay, as essential as the writing. Though Smith places his work at the crosscurrents of various aesthetic influences (such as the painter Edward Hopper), what stands out the most in this taciturn, thoughtful piece of writing is his use of the second person to address the reader directly. Suddenly, the writer steps out of the body of the essay and makes eye contact with the reader. The reader is now part of the story as a second character, finally entering the picture.

Short Fiction

The short story is the happy medium of fiction writing. These bite-sized narratives can be devoured in a single sitting and still leave you reeling. Sometimes viewed as a stepping stone to novel writing, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Short story writing is an art all its own. The limited length means every word counts and there’s no better way to see that than with these two examples:

“An MFA Story” by Paul Dalla Rosa (Electric Literature)

At Starbucks, I remembered a reading Zhen had given, a reading organized by the program’s faculty. I had not wanted to go but did. In the bar, he read, "I wrote this in a Starbucks in Shanghai. On the bank of the Huangpu." It wasn’t an aside or introduction. It was two lines of the poem. I was in a Starbucks and I wasn’t writing any poems. I wasn’t writing anything.

This short story is a delightfully metafictional tale about the struggles of being a writer in New York. From paying the bills to facing criticism in a writing workshop and envying more productive writers, Paul Dalla Rosa’s story is a clever satire of the tribulations involved in the writing profession, and all the contradictions embodied by systemic creativity (as famously laid out in Mark McGurl’s The Program Era). What’s more, this story is an excellent example of something that often happens in creative writing: a writer casting light on the private thoughts or moments of doubt we don’t admit to or openly talk about.

“Flowering Walrus” by Scott Skinner (Reedsy)

I tell him they’d been there a month at least, and he looks concerned. He has my tongue on a tissue paper and is gripping its sides with his pointer and thumb. My tongue has never spent much time outside of my mouth, and I imagine it as a walrus basking in the rays of the dental light. My walrus is not well.

A winner of Reedsy’s weekly Prompts writing contest, ‘Flowering Walrus’ is a story that balances the trivial and the serious well. In the pauses between its excellent, natural dialogue, the story manages to scatter the fear and sadness of bad medical news, as the protagonist hides his worries from his wife and daughter. Rich in subtext, these silences grow and resonate with the readers.

Want to give short story writing a go? Give our free course a go!

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

Novels

Perhaps the thing that first comes to mind when talking about creative writing, novels are a form of fiction that many people know and love but writers sometimes find intimidating. The good news is that novels are nothing but one word put after another, like any other piece of writing, but expanded and put into a flowing narrative. Piece of cake, right?

To get an idea of the format’s breadth of scope, take a look at these two (very different) satirical novels:

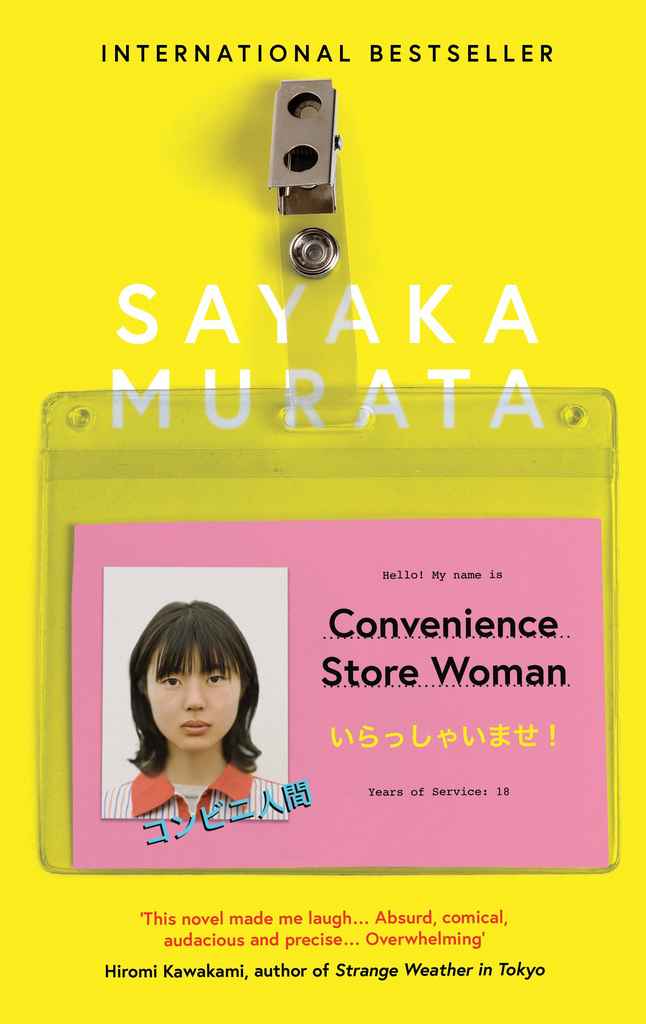

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this. Once we donned our uniforms, we were all equals regardless of gender, age, or nationality — all simply store workers.

Keiko, a thirty-six-year-old convenience store employee, finds comfort and happiness in the strict, uneventful routine of the shop’s daily operations. A funny, satirical, but simultaneously unnerving examination of the social structures we take for granted, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is deeply original and lingers with the reader long after they’ve put it down.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The hard, gritty truth of the matter is that I hardly ever think about race. Those times when I did think about it a lot I did so because of my guilt for not thinking about it.

Erasure is a truly accomplished satire of the publishing industry’s tendency to essentialize African American authors and their writing. Everett’s protagonist is a writer whose work doesn’t fit with what publishers expect from him — work that describes the “African American experience” — so he writes a parody novel about life in the ghetto. The publishers go crazy for it and, to the protagonist’s horror, it becomes the next big thing. This sophisticated novel is both ironic and tender, leaving its readers with much food for thought.

Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is pretty broad: it applies to anything that does not claim to be fictional (although the rise of autofiction has definitely blurred the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction). It encompasses everything from personal essays and memoirs to humor writing, and they range in length from blog posts to full-length books. The defining characteristic of this massive genre is that it takes the world or the author’s experience and turns it into a narrative that a reader can follow along with.

Here, we want to focus on novel-length works that dig deep into their respective topics. While very different, these two examples truly show the breadth and depth of possibility of creative nonfiction:

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Men’s bodies litter my family history. The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.

Writer Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five men from her rural Mississippi community in as many years. In her award-winning memoir, she delves into the lives of the friends and family she lost and tries to find some sense among the tragedy. Working backwards across five years, she questions why this had to happen over and over again, and slowly unveils the long history of racism and poverty that rules rural Black communities. Moving and emotionally raw, Men We Reaped is an indictment of a cruel system and the story of a woman's grief and rage as she tries to navigate it.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker

He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life. That’s why he preferred buying bottles to splurging on sweaters. Sweaters were things. Bottles of wine, said Morgan, “are ways that my humanity will be changed.”

In this work of immersive journalism, Bianca Bosker leaves behind her life as a tech journalist to explore the world of wine. Becoming a “cork dork” takes her everywhere from New York’s most refined restaurants to science labs while she learns what it takes to be a sommelier and a true wine obsessive. This funny and entertaining trip through the past and present of wine-making and tasting is sure to leave you better informed and wishing you, too, could leave your life behind for one devoted to wine.

Illustrated Narratives (Comics, graphic novels)

Once relegated to the “funny pages”, the past forty years of comics history have proven it to be a serious medium. Comics have transformed from the early days of Jack Kirby’s superheroes into a medium where almost every genre is represented. Humorous one-shots in the Sunday papers stand alongside illustrated memoirs, horror, fantasy, and just about anything else you can imagine. This type of visual storytelling lets the writer and artist get creative with perspective, tone, and so much more. For two very different, though equally entertaining, examples, check these out:

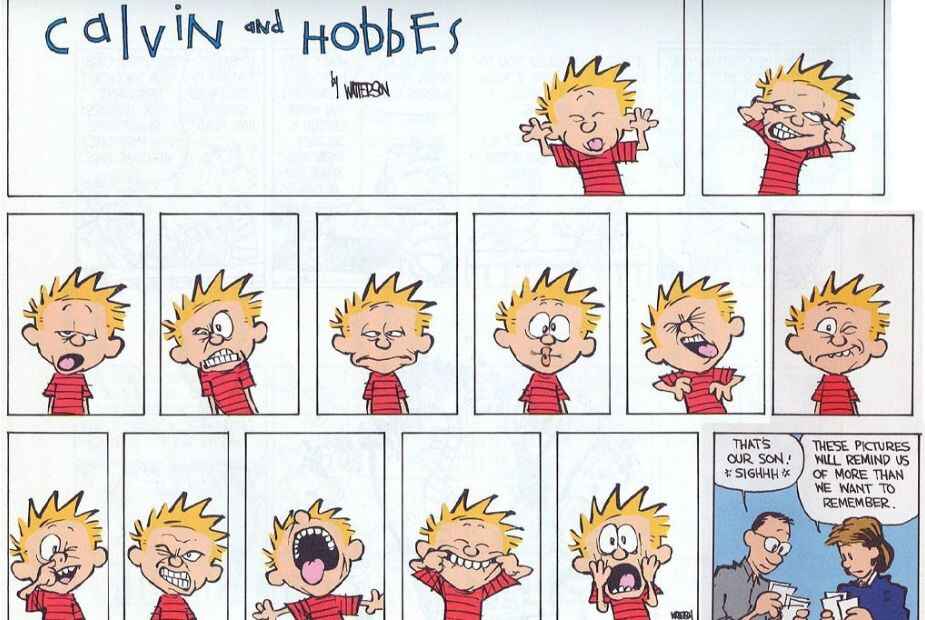

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

"Life is like topography, Hobbes. There are summits of happiness and success, flat stretches of boring routine and valleys of frustration and failure."

This beloved comic strip follows Calvin, a rambunctious six-year-old boy, and his stuffed tiger/imaginary friend, Hobbes. They get into all kinds of hijinks at school and at home, and muse on the world in the way only a six-year-old and an anthropomorphic tiger can. As laugh-out-loud funny as it is, Calvin & Hobbes’ popularity persists as much for its whimsy as its use of humor to comment on life, childhood, adulthood, and everything in between.

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

"I shall tell you where we are. We're in the most extreme and utter region of the human mind. A dim, subconscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves. Hell, Netley. We're in Hell."

Comics aren't just the realm of superheroes and one-joke strips, as Alan Moore proves in this serialized graphic novel released between 1989 and 1998. A meticulously researched alternative history of Victorian London’s Ripper killings, this macabre story pulls no punches. Fact and fiction blend into a world where the Royal Family is involved in a dark conspiracy and Freemasons lurk on the sidelines. It’s a surreal mad-cap adventure that’s unsettling in the best way possible.

Video Games and RPGs

Probably the least expected entry on this list, we thought that video games and RPGs also deserved a mention — and some well-earned recognition for the intricate storytelling that goes into creating them.

Essentially gamified adventure stories, without attention to plot, characters, and a narrative arc, these games would lose a lot of their charm, so let’s look at two examples where the creative writing really shines through:

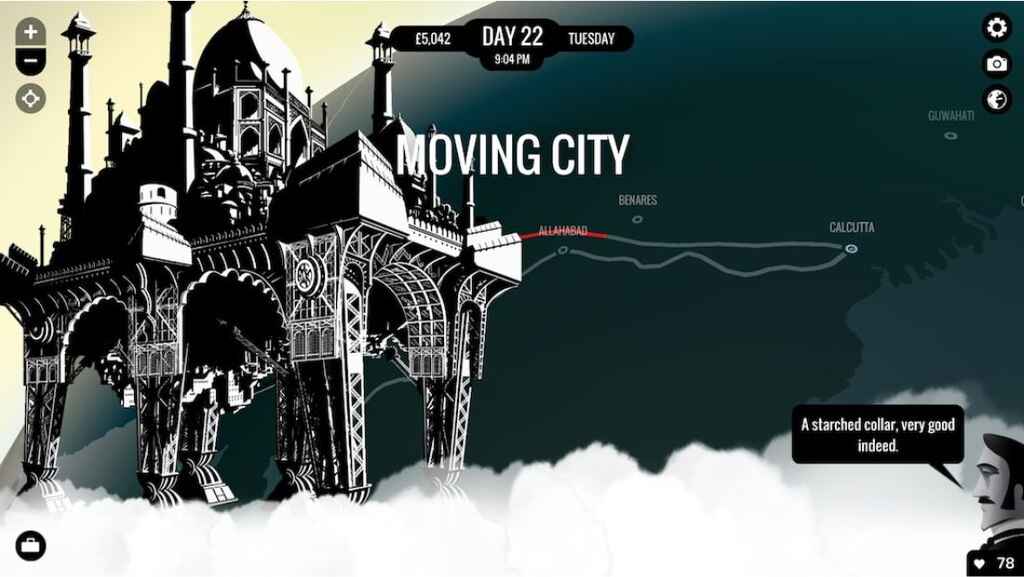

80 Days by inkle studios

"It was a triumph of invention over nature, and will almost certainly disappear into the dust once more in the next fifty years."

Named Time Magazine’s game of the year in 2014, this narrative adventure is based on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne. The player is cast as the novel’s narrator, Passpartout, and tasked with circumnavigating the globe in service of their employer, Phileas Fogg. Set in an alternate steampunk Victorian era, the game uses its globe-trotting to comment on the colonialist fantasies inherent in the original novel and its time period. On a storytelling level, the choose-your-own-adventure style means no two players’ journeys will be the same. This innovative approach to a classic novel shows the potential of video games as a storytelling medium, truly making the player part of the story.

What Remains of Edith Finch by Giant Sparrow

"If we lived forever, maybe we'd have time to understand things. But as it is, I think the best we can do is try to open our eyes, and appreciate how strange and brief all of this is."

This video game casts the player as 17-year-old Edith Finch. Returning to her family’s home on an island in the Pacific northwest, Edith explores the vast house and tries to figure out why she’s the only one of her family left alive. The story of each family member is revealed as you make your way through the house, slowly unpacking the tragic fate of the Finches. Eerie and immersive, this first-person exploration game uses the medium to tell a series of truly unique tales.

Humor

Fun and breezy on the surface, humor is often recognized as one of the trickiest forms of creative writing. After all, while you can see the artistic value in a piece of prose that you don’t necessarily enjoy, if a joke isn’t funny, you could say that it’s objectively failed.

With that said, it’s far from an impossible task, and many have succeeded in bringing smiles to their readers’ faces through their writing. Here are two examples:

‘How You Hope Your Extended Family Will React When You Explain Your Job to Them’ by Mike Lacher (McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

“Is it true you don’t have desks?” your grandmother will ask. You will nod again and crack open a can of Country Time Lemonade. “My stars,” she will say, “it must be so wonderful to not have a traditional office and instead share a bistro-esque coworking space.”

Satire and parody make up a whole subgenre of creative writing, and websites like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Onion consistently hit the mark with their parodies of magazine publishing and news media. This particular example finds humor in the divide between traditional family expectations and contemporary, ‘trendy’ work cultures. Playing on the inherent silliness of today’s tech-forward middle-class jobs, this witty piece imagines a scenario where the writer’s family fully understands what they do — and are enthralled to hear more. “‘Now is it true,’ your uncle will whisper, ‘that you’ve got a potential investment from one of the founders of I Can Haz Cheezburger?’”

‘Not a Foodie’ by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell (Electric Literature)

I’m not a foodie, I never have been, and I know, in my heart, I never will be.

Highlighting what she sees as an unbearable social obsession with food, in this comic Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell takes a hilarious stand against the importance of food. From the writer’s courageous thesis (“I think there are more exciting things to talk about, and focus on in life, than what’s for dinner”) to the amusing appearance of family members and the narrator’s partner, ‘Not a Foodie’ demonstrates that even a seemingly mundane pet peeve can be approached creatively — and even reveal something profound about life.

We hope this list inspires you with your own writing. If there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be that there is no limit to what you can write about or how you can write about it.

In the next part of this guide, we'll drill down into the fascinating world of creative nonfiction.