Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

How to Write a Self-Help Book (That Actually Helps People)

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →You’ve overcome an obstacle or problem and learned some important life lessons — now you want to write a self-help book and share your experience and wisdom with other people. You’re ready to give them the tools they need to grow and improve their lives.

This post walks you through the whole process, sharing some tips from expert self-help editors on the Reedsy marketplace. Here’s how you can write your own self-help book:

- 1. Identify a specific problem your book will remedy

- 2. Make your readers believe you can help them

- 3. Don’t forget that you’re telling a story

- 4. Give your readers specific actions they can take

- 5. Pick an appealing and informative title (and subtitle)

- 6. Always cite your sources

- 7. Give readers something extra at the end

1. Identify a specific problem your book will remedy

To some extent, nonfiction books (with the important exception of memoirs and creative nonfiction) are about identifying a problem and offering a solution. This could mean practical, step-by-step advice or a deeper, more nuanced understanding of an existing situation that changes the reader’s perception. Self-help books are no different: your job as a writer is to zero in on a particular problem, and provide your reader a way to deal with it.

Accept that you need to limit your scope

Many self-help writers begin with a very general idea, like overcoming mental illness or becoming a happier person. Broad, abstract topics like this are great as a first instinct, but you’ll need to refine the scope of your book for the sake of your readers, your sanity, and your commercial potential.

Abstract concepts are hard to comprehensively address in a helpful way that provides concrete insights and advice. They’re also notoriously difficult to sell to a traditional self-help publisher, who will be looking for something new and unique with a defined target audience. As of March 2022, there are over 70,000 titles in the Self-Help category on Amazon — so writing a generic book about “finding happiness” won’t quite cut it.

Distill your idea

A good way to focus the scope of your book is to fill in the blanks of this imaginary pledge to your reader:

If you are ____ and your problem is ____, I can help you by ____.

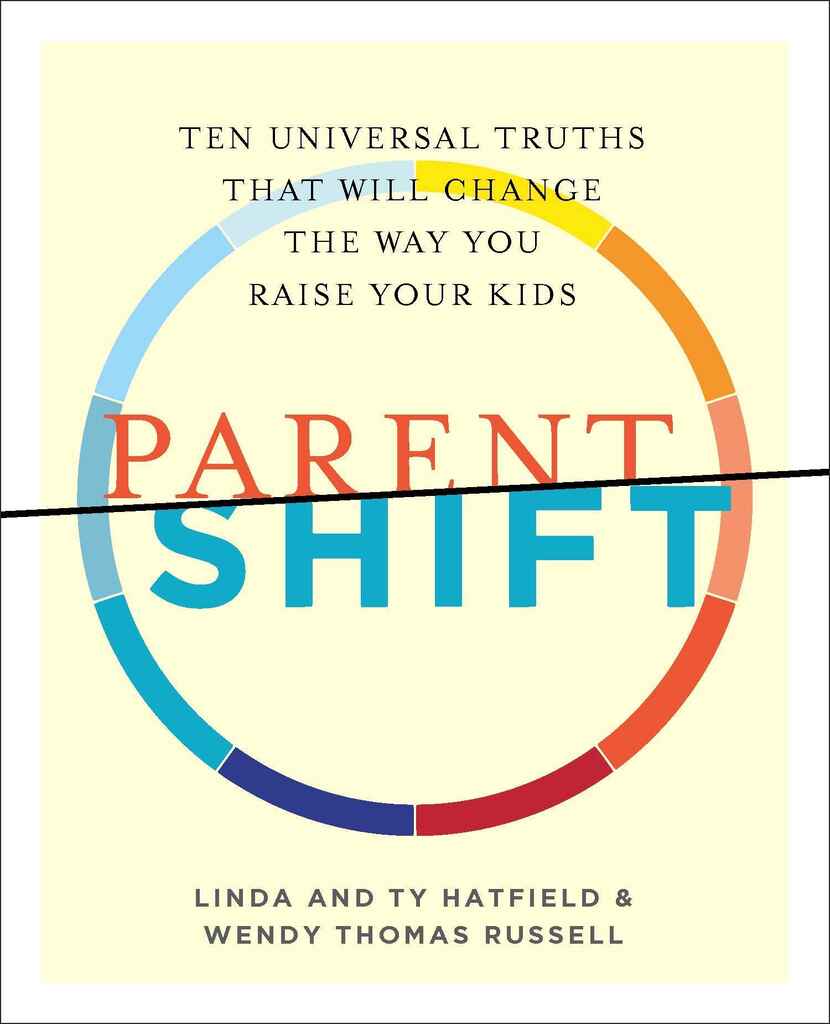

This pledge helps you identify your audience, the problem they’re facing, and its solution. We’ll use ParentShift: Ten Universal Truths That Will Change the Way You Raise Your Kids by Wendy Thomas Russell, Linda Hatfield, and Ty Hatfield as a vehicle to explore all three.

Audience

Understanding your target audience is crucial when writing any type of nonfiction. Not only will it help you market your book to sell more books, but it will also be the driving force that shapes your book and helps you write it well. After all, how can you help someone if you don’t know who they are and what they need?

So ask yourself who will gain the most from the material in your book. The answer should be as specific as possible. Let’s look at ParentShift: Ten Universal Truths That Will Change the Way You Raise Your Kids.

It’s safe to assume that this book is aimed at parents — but what kind of parents? Well, the heart of this book is about transforming how parents approach temper tantrums and timeouts, so we might say that this book is specifically targeted at new parents who’ve run out of options.

It’s safe to assume that this book is aimed at parents — but what kind of parents? Well, the heart of this book is about transforming how parents approach temper tantrums and timeouts, so we might say that this book is specifically targeted at new parents who’ve run out of options.

And don’t just stop there, think about location, cultural context, and occupation: parents who work full-time might especially need fast solutions — with triple shifts, play dates and a mountain of housework to stay on top of, ten universal truths might be as much as they can handle. The more detail you have on your demographic, the easier it will be to target them.

Problem

After you’ve located your target audience, figure out the precise aspects of their problem (or “pain point”) and identify the many shapes they might take. ParentShift, for example, immediately sets up a problem: you’re struggling with raising your children, you know it, and common parenting methods aren’t working for you.

When you’ve identified your central problem, make it visible in the title, subtitle, or blurb, so that your audience can tell that this book is for them right away.

Solution

How does a book on terrible teens and toddlers solve the problem of mediocre parenting? Well, as ParentShift’s blurb notes, it “challenges some of our most popular disciplinary tools and replaces them with more than a dozen ‘toolkits’ designed to help parents solve virtually any household without sabotaging their long term goals.” In other words, this book helps you analyze your problem in new ways, and shows you alternative courses of action.

Presumably, this is the kind of insight that made you want to write a book in the first place, so we’ll assume you have a good understanding of your own ideas here — but just in case the thoughts are getting jumbled in your mind, try talking out your ideas with a friend to make sure they’re easy to understand and you’re able to communicate them clearly. Then put pen to paper, and repeat the process!

2. Make your readers believe you can help them

The success of a self-help book hinges entirely on your credibility and authority as a writer. After all, you wouldn’t wander down the street asking random people to help you improve your life, would you? That’s why you’ll often see beloved media personalities publish self-help books: they have an inbuilt audience of people who already trust them.

But how can you create trust with prospective readers if you’re not Russell Brand or Oprah Winfrey? Two ways to do this involve sharing facts about yourself — the third, and sometimes forgotten one, has to do with style and structure.

Qualifications tell readers others can vouch for your knowledge

One way in which authors can show that they’re authoritative sources is by noting any relevant qualifications. For example, Brené Brown regularly cites her work as a researcher and psychology professor when examining the kinds of people who struggle to be vulnerable in her book Daring Greatly. But university degrees aren’t the only qualification that matters — take Matthieu Ricard, for example, whose book The Art of Meditation is infinitely more appealing because of the fact that its writer is a Buddhist monk, and so someone the reader trusts to know meditation well.

Personal experiences say “I’ve been there”

By opening up and sharing stories from your personal past, you show readers you’re speaking from real, first-hand experience — not just theorizing from a distance. For example, Louise Hay’s self-help classic, The Power Is Within You, followed her many years of work with HIV/AIDS patients and her own experience of cervical cancer, and focuses on how positive thought patterns can help lead to improved wellbeing. Were Hay not speaking from experience, skeptical readers might struggle to see why they should read her book — but by letting millions of readers walk a mile in her shoes, she gave them a reason to listen to what she had to say.

Persuasive style and structure matter the most

While it’s important that readers can see that you are worthy of their trust, resist the urge to turn your book into a LinkedIn page of your Expert Qualifications.

Elaine O’Neill, a former Hay House Commissioning Editor, points out that self-help writers often miss a trick in getting readers to believe in them by neglecting style and structure:

"One mistake that I find new self-help authors make more often than anything else is forgetting their reader. They believe they have to include everything they've learned into their manuscript, without thinking about what the reader needs to learn, and how to feed it to them bit by bit. Authors can show their authority by really knowing their reader inside out and speaking to them directly, by sharing their own recovery from the same issue.

“You want the reader to feel seen by you, and once they do, they'll trust your expertise because you've been there — and you can see they are too.”

Didacticism never works

Fiction readers are notoriously intolerant of didactic narratives — self-help books are a slightly different story, because the writer is, by default, in the position of a teacher. That said, no one likes to be spoken down to, and a superior tone will not help you assert your expertise. You aren’t running for president of the Nobel committee — you just want a reader to like you enough to listen, so make an effort to communicate your knowledge in a style of language that speaks to them.

📚 Still not sure how to present yourself? Head to our list of the 50 Best Self-Help Books of All Time and check out how each of these authors presents themselves as an authority figure.

3. Don’t forget that you’re telling a story

Self-help books rarely follow a single, overarching story shape and arc. Typically, they’re guided not by a narrative but by an argument or thesis — with chapters structured around stories that help illustrate the points made.

Structure intuitively for a great reading experience

How do you make sure your book is readable, compact, and flows logically from chapter to chapter? By committing to a detailed plan of your book before you even start to write. In traditional publishing, you will almost always first draft a proposal which will serve as an excellent plan. But even if you’re self-publishing, making a plan is well worth your time to ensure that every chapter is necessary and contributes value.

As with novels, good beginnings can make or break a self-help book. Your introduction should tell readers a little about you and why you’re writing a book. It should also give them a quick, at-a-glance summary of what will follow. Chapter 1 is where you’ll start getting to the meat of things, sketching out the complexities of the central problem. After that, it’s up to you how the rest of the book will be structured.

If this is a point you’re really struggling with, focus on getting all your thoughts out instead, and make a note of questions or concerns to bring up with your editor later. Speaking of editors, you can request quotes from some of the best self-help editors in the industry for free, right here on Reedsy:

Give your book the help it deserves

The best self-help editors are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

Solidify through anecdotes and emotional storytelling

Ideally, you should structure each chapter of your self-help book around a specific point or insight — and the best way to illustrate each point is through a story or anecdote, whether it’s personal, hypothetical, or entirely fictional. Stories have the great effect of eliciting an emotional response or more active interest by involving a character that readers can empathize with or watch with curiosity.

Need an example? Think of the way Christianity’s teachings are shared through the parables Jesus taught lessons with: the story of the good Samaritan is infinitely more memorable than “be kind.”

Storytelling also creates interest and tension, keeping readers invested — take a look at Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, the first chapter of which starts as follows:

“On May 7, 1931, the most sensational manhunt New York City had ever known had come to its climax. After weeks of search, ‘Two Gun’ Crowley—the killer, the gunman who didn’t smoke or drink—was at bay, trapped in his sweetheart’s apartment on West End Avenue.”

Only tell stories that add to your message

Self-help editor Danielle Goodman emphasizes the need to only tell stories worth telling: “When it comes to self-help books, proof of concept is absolutely necessary. That’s why story-telling can be so powerful. It lifts your advice from the page and places it in the real world of real people, like yourself and your readers.

“The main question to ask yourself when telling pieces of your story is: Is what I’m writing in service of my message? In other words, how does this story underscore what you want the reader to feel, understand, and act on?

“Once you know the answer, be explicit in connecting the dots for the reader. Tell them exactly why you included this story and what you want them to get out of it. And if you can’t quite figure out why this story is important to your message, leave it out for now.”

4. Give your readers specific actions they can take

The self-help genre is often more abstract than, say, how-to guides or even memoir, so your book may run the risk of being too woolly in its advice. And if you’ve ever tried to get travel directions from someone who sorta kinda knows the way to the library, you’ll know how frustrating vagueness can be.

Self-help editor Kate Victory Hannisian says that “one indicator that you haven’t made your self-help advice completely clear is a comment from editors or beta-readers like this: ‘Great, but how does someone actually DO that?’

“Sometimes the solution is to see if you can break that advice into bite-sized, actionable steps. Other times, adding specific examples and vivid anecdotes with a few well-chosen details can help make your advice real and relatable for your target reader, and thus more useful to them. Depending on the type of self-help book you’re writing, these examples may come from your own experience or other sources, but the key is knowing that it’s important to show, don’t tell — even in nonfiction writing.”

Free course: How to Master the ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ Rule

You've probably heard this classic piece of writing advice a thousand times. But what does ‘Show, Don't Tell’ actually mean?

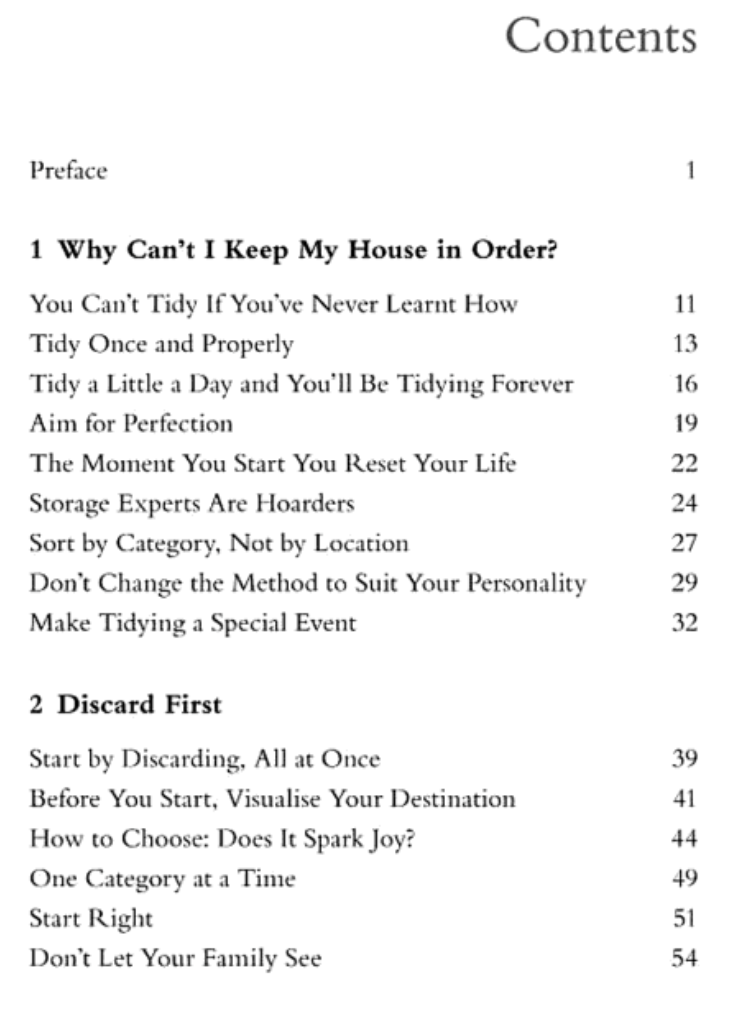

To make sure your actionable points aren’t lost in the storytelling, you can offer a recap at the end of each chapter. Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein’s A Hunter-Gatherer's Guide to the 21st Century re-iterates each of its chapters perfectly, summarizing the main takeaways in bullet points — but you can go a step further and offer a checklist of actions to take or questions the reader can ask themselves to diagnose their own needs.

5. Pick an appealing and informative title (and subtitle)

Self-help titles are generally pretty formulaic, and nearly always include a subtitle:

[Attention-Grabbing Phrase]:[Description of the Book]

You can see this formula in action with self-help titles like:

- The 4-Hour Work Week: Escape the 9-5, Live Anywhere and Join the New Rich

- The Self-Love Habit: Transform fear and self-doubt into serenity, peace and power

- The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook: A Proven Way to Accept Yourself, Build Inner Strength, and Thrive

So what do you need to bear in mind when you find a title for your own book? Let’s do a super-quick linguistic analysis of this genre’s common title elements. 🧠

a) Direct address

Many self-help titles address the reader directly with the second person pronoun ‘you’. As with fiction written in second person point of view, directly addressing your reader has an immediate and personal effect, especially if the title catches a reader’s eye on a store shelf or online. Here are a few examples:

- You Are a Badass by Jen Sincero

- Make Your Bed by Admiral William H. McRaven

- Declutter Your Mind by S.J. Scott and Barrie Davenport

- Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin & Joe Dominguez

b) Imperatives

Authoritative statements are attention-grabbing in the same way that second person is: by being immediate. Titles that use imperatives put this most powerful of grammatical moods to use in order to command the reader’s attention. Can’t think of any? Here’s a few:

- Stay Sexy & Don't Get Murdered by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark

- Stick with Exercise for a Lifetime by Robert Hopper

- Find Your Artistic Voice by Lisa Congdon

- Keep Going by Austin Kleon

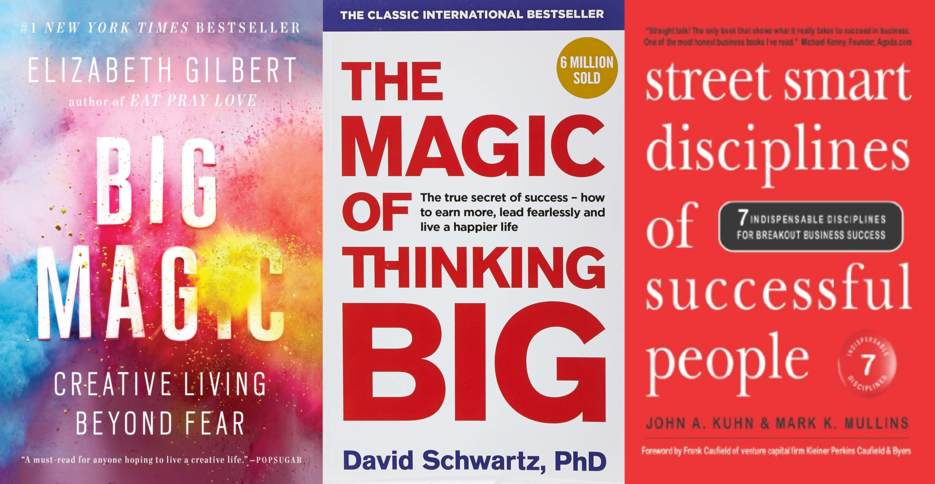

c) An inspirational tone

Whether they evoke a sense of magic, or are simply a sweet combination of words that offer a momentary glimpse of possibility, self-help titles are particularly prone to taking on an inspirational tone. Inspirational titles might mention happiness, success, or a whole host of other positive abstract nouns: growth, change, improvement. How do they work? By promising wonderful things ahead. A few examples for you:

Whether they evoke a sense of magic, or are simply a sweet combination of words that offer a momentary glimpse of possibility, self-help titles are particularly prone to taking on an inspirational tone. Inspirational titles might mention happiness, success, or a whole host of other positive abstract nouns: growth, change, improvement. How do they work? By promising wonderful things ahead. A few examples for you:

- Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert

- Radical Acceptance by Tara Brach

- The Magic of Thinking Big by David J. Schwartz

- Street Smart Disciplines of Successful People by Mark Mullins and John Kuhn

d) Search-optimized subtitle

When self-help covers feature these inspirational titles, they often need a subtitle to contextualize the contents of the book. These relatively prosaic second titles give a more informative description of what readers can expect.

🚨Watch your capitals! Head over to our post covering established title capitalization rules to make sure your title is correct.

That much is obvious — what fewer people realize is that titles are often search-optimized, meaning that they are written to contain some important keywords or terms related to the topic being discussed. This helps the book be found by readers searching for those terms on Amazon. Take a look at the titles below, and notice the keywords in their subtitles — bolded for your convenience:

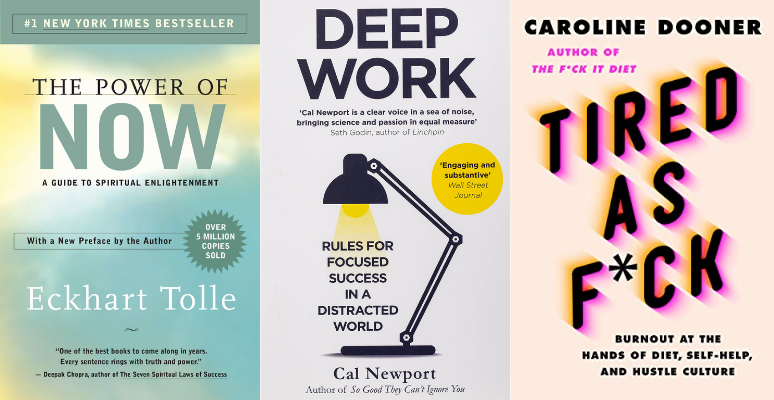

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle

- Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport

- Stolen Focus: Why You Can't Pay Attention — And How to Think Deeply Again by Johann Hari

- Tired as F*ck: Burnout at the Hands of Diet, Self-Help, and Hustle Culture by Caroline Dooner

Confused? It’s got to do with the way Amazon’s algorithms work, as Reedsy co-founder Ricardo Fayet explains in his free book How to Market a Book.

“If your book is ‘indexed’ for a keyword, that means it will turn up as a result when a customer enters that term into the Amazon search bar. For example, more than nine thousand e-books are indexed on the Kindle Store for “herbal remedies.” [...] The closer the match between your title, or a part of your title, and the search keyword, the higher your book will rank.”

Looking for more marketing insights? You can download Ricardo’s book for free below:

6. Always cite your sources

It’s unlikely that you’re the first person to ever write about your topic, or even give advice about your topic. That’s okay — different people can give different, and still useful, advice on the same issues, so don’t feel like your idea is “taken.”

The important thing is to acknowledge those who have informed your research, clearly giving them credit for ideas they have contributed. By all means add to these or expand them, but, as many a disgruntled undergraduate can attest, you should never present them as your own: that’s intellectual property theft at worst — and at best, very uncool.

Instead, be gracious: cite your sources, describe their positions if they differ from yours, and situate yourself as one of the many voices in this dialogue. Take Cal Newport as your example — his introduction of previous contributions on the subject of technology being distracting is a masterclass in sketching out an existing discussion and clarifying your place in it:

“[This idea] is not new. [Nicholas Carr’s] The Shallows was just the first in a series of recent books to examine the Internet’s effect on our brains and work habits. These subsequent titles include William Powers’s Hamlet’s BlackBerry, John Freeman’s The Tyranny of E-mail, and Alex Soojung-Kin Pang’s The Distraction Addiction—all of which agree, more or less, that network tools are distracting us from work that requires unbroken concentration, while simultaneously degrading our capacity to remain focused. Given this existing body of evidence, I will not spend more time in this book trying to establish this point.”

— Cal Newport, 'Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World'

7. Give readers something extra at the end

Consider this a bonus step, particularly useful to those writers who hope to make a living from their writing careers. Supposing a reader has finished your book, you know that you have an interest in common with them — so there may be more they can learn from you.

If you’re active on social media, teach a video course, or offer further resources on similar topics freely available on your platform, mention this in your book. Even if you have none of these things at the moment, you can offer a simple and free resource that complements your book, like a printable checklist the reader can download for easy reference. The idea is that you’ll point the reader to your website, and offer them a “reader magnet,” in other words allow them to download something in exchange for them signing up to your mailing list… which you’ll need to set up if you don’t already have one!

Why bother with all this? Because, as Reedsy’s Ricardo Fayet asserts in his free Reedsy Learning course on mailing lists, “your author mailing list is the one main tool you’ll use to build a long-lasting relationship with your readers, turning them into repeat buyers and unconditional fans. Every sale you make while your mailing list is not in place is basically a lost opportunity.”

Free course: Author Mailing Lists

Acquire more readers, sell more books, and make more money with the only indispensable tool in the book marketer's arsenal. Get started now.

When written with care, self-help books can boost their writer’s career, turn seriously profitable, and actually help people improve their lives. It’s a win-win if ever there was one, so take the time to polish yours and you won’t regret it. Good luck!