Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

Dénouement: Definition, Tips, and Examples

Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

View profile →The dénouement is the last beat of a fictional story. It should provide a degree of closure, answer lingering narrative questions, and tie up any loose ends. In this post, we’ll look at some hallmarks of this element of plot structure, the purpose the dénouement serves in fiction, and the differences between dénouement and other common story endings.

What is the dénouement in a story?

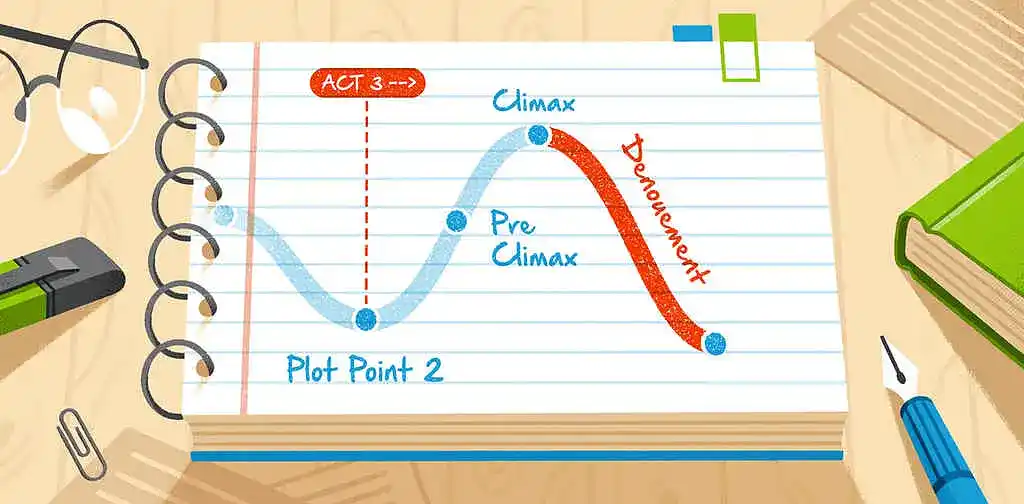

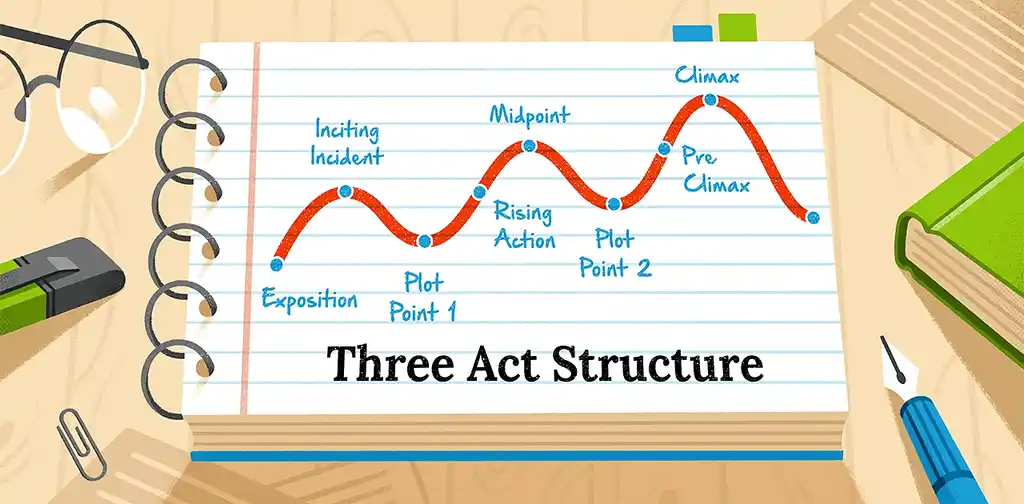

A dénouement (pronounced day-noo-MAAN) consists of the final moments in a fictional work — the closing sequence that follows the climax of a story (where narrative tension has reached its highest point) and the falling action of the story (where that tension begins to come down). The word comes from the French verb dénouer, which means “to unravel.” You can think of a dénouement as your last chance to deal with any knotty problems that remain unsolved by the end of the story.

You’ll also notice that the dénouement is a mainstay in many popular story structures, including Freytag’s Pyramid and the three-act structure. A good one simply ties up all loose ends. A great one leaves readers feeling satisfied — and keeps them thinking about your story’s central themes, long after the story is over.

Example: One of the most famous examples of the dénouement is the reveal at the end of mystery novels. With the killer unmasked and justice served, the detective (or narrator) gathers interested parties into a room and then dramatically does a tell-all.

It ties up loose ends

As we mentioned, the word dénouement comes from the French word for “untie.” However, a good dénouement often does the opposite: it aims to give readers a satisfying conclusion by tying up dangling narrative threads.

Some genres come with the inherent expectation of a rounded-out narrative. We all know that romance novels, for example, typically conclude with a “happily ever after” for the leading couple. But what about any other unresolved subplots? Did our heroine get that job she interviewed for? Did the best friend and the cute baker ever get together? Well, they’re also addressed in the dénouement.

💌 Curious about romance tropes beyond “happily ever after”? Check out our list of 11 popular romance tropes.

Mystery novels also famously tie up loose ends in the dénouement — at least all the ones that pertain to the mystery at hand. The narrative arc reaches its climactic peak when the clues come together, and the guilty party is uncovered. In the dénouement that follows, when the villain is apprehended, the detective (or the narrator) reveals how they cracked the case.

Of course, a dénouement is more than just an act of narrative housekeeping — it can also serve a more visceral purpose within a story.

It releases tension

A well-told story will inevitably build tension throughout the narrative. While this may not always take the form of suspense, the stakes ratchet up, or the protagonist’s odds of getting what they want grow slimmer — building to a climax. This climax is the moment of maximum tension and should have the reader on the edge of their seat.

After the excitement and anxiety of the climax, the dénouement should return a sense of calm, allowing readers to reflect on what has happened and what it means for the characters involved.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

It reflects on a character’s journey

Many novels feature some kind of “character vs. self” conflict, where the protagonist can only achieve their goal once they recognize that they are their own main obstacle. This might be the main conflict of the story (a movie star must overcome their ego to find happiness) or a sub-conflict that mirrors a character’s external conflict (a greedy tech bro wrestles with the need to defeat an AI that’s programmed to accumulate wealth). Regardless, it’s this internal conflict that drives the character arc — the inner journey that unfolds over the course of the plot.

Just as the narrative arc comes to a head at the climax, so will the character arc. Readers will, therefore, want to know what effect the climax has had on the character and their personal journey. Enter the dénouement: here, we should get a sense of how the events of the story have impacted the characters — and whether they have changed for the better, for the worse, or not at all.

The dénouement might also have something larger to say, which brings us to our next point.

It plays one final thematic beat

Like Aesop’s fable of “The Tortoise and the Hare”, many stories explicitly state their moral lesson at the end. Here, it’s “slow and steady wins the race”. But unless you’re writing an anthology of overbearing parables, you probably shouldn’t spoon-feed your readers like this. Still, a dénouement can be a great place to give a final, subtle nod to your novel’s theme or motifs. Try not to be heavy-handed or repetitive — simply offer an insight that gives your readers one last thought to chew on.

But unless you’re writing an anthology of overbearing parables, you probably shouldn’t spoon-feed your readers like this. Still, a dénouement can be a great place to give a final, subtle nod to your novel’s theme or motifs. Try not to be heavy-handed or repetitive — simply offer an insight that gives your readers one last thought to chew on.

If you’re thinking that dénouements are all about leaving no stone unturned, remember that the most thought-provoking endings are often ambiguous.

It leaves the end on a question mark

Stories that end by wrapping all their messy threads into a bow can often feel a little contrived and jolt readers out of the narrative (the final season of Downton Abbey, anyone?). As such, some authors opt for a dénouement that leaves a few lingering questions in the characters’ minds — and the feeling that there’s still more to be said.

Authors who want readers to reflect on their story well after the final words can end their novel by implying that the characters’ lives will continue. This could be done by nudging at future events or by pointing out that there remain minor conflicts that haven’t yet been worked out. Ambiguous endings provide readers with a sense of longing and keep your book in their minds. As they say in showbiz: leave them wanting more!

Authors can also leave a thematic or practical unanswered question for readers to reflect on. By giving readers more to think about, authors can make a lasting impression.

All the features of a dénouement that we’ve mentioned so far have been artistic in nature. However, there’s one last variety that’s a bit more on the commercial side.

It sets up a potential sequel

There’s nothing more frustrating than reading hundreds of pages, only to find that the story is totally open-ended. And yet, there’s nothing more exciting than learning that your favorite novel is the first in a series and starting that second book, keenly anticipating answers that the first installment didn’t supply.

While a cliffhanger can be a great hook for the next novel, authors should approach cliffhangers with caution when not writing a sequel. Many readers consider sudden plot-twist endings that don’t provide a sense of resolution to be a betrayal of their trust. So if a standalone novel does end on a cliffhanger, the author must adequately lay the groundwork so that readers aren’t caught off-guard. A bit of foreshadowing can save them from feeling like the rug has been swept out from under them. In other words, a cliffhanger should leave readers speculating, not consternating.

Setting up a sequel doesn’t necessarily mean you need to end on a cliffhanger, either. Authors can tease a follow-up either by leaving readers with a lingering question, as described above, or by redefining the characters’ goal to set up a future plot — “Now that we’ve retrieved the magical sword, we need to return it to the dragon’s lair,” etc.

Reading new books in your genre is a great way to get a sense of what makes a dénouement work, but we’ll walk through a few examples to get you started.

4 examples of dénouement (spoilers ahead!)

To better understand what makes a dénouement work, let’s take a look at a few books whose authors have nailed this crucial conclusion.

1. The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins

In this story of deception and mistaken identity, the dénouement takes place after the death of the story’s villain, Sir Percival Glyde. We learn that Sir Percival had committed his bride, Laura, to an asylum under the name of another woman, Anne, who died soon after and was buried in Laura’s place. When Laura’s true beloved learns of the deception, he is able to free her from the asylum, and they have their happily ever after.

Part of why this ending works so well is because it satisfies the expectations that come with the genre. It’s an incredibly fitting final beat for a story that combines the structure of a Victorian novel with the intrigue and suspense of detective fiction, both genres favoring closure in the form of a dénouement.

2. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Following the dramatic death of Myrtle Wilson and the low-key murder of the titular character, The Great Gatsby’s dénouement is a decidedly somber affair.

Through Nick’s narration, we see the fallout from Gatsby’s death: his sparsely attended funeral and a reluctant admission of responsibility on the part of Tom Buchanan, which ultimately comes too late. Nick returns to the Midwest, too disturbed by what’s unfolded to stay in New York. We join him in reflecting on what took place, and what any of it meant.

The reflective dénouement fits the deliberate pace of the rest of the novel and resurfaces the novel’s central themes: the improbability of the American Dream, the danger of wealth, and the hopeless longing of nostalgia.

3. Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Throughout Hurston’s novel, protagonist Janie struggles with self-actualization. In the beginning of the novel, Janie barely speaks and can’t advocate for herself. A helpless observer of her own story, she’s trapped in a parade of loveless and controlling marriages. But during the novel’s climax, she finally takes action, shooting her third and final husband after he attacks her in a (literal) rabid rage.

In the novel’s dénouement, Janie finds a new sense of agency. She fights for herself in court and shares her story with other women on her own terms, no longer invisible or ignored. While Janie’s story is a personal one, its dénouement makes a larger point about society in general (especially, here, about the lives of marginalized women), inviting readers to think about how their real life relates to the story.

4. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

For a dénouement that hits a theme on the head without overtly stating it, we can turn to Harper Lee’s classic novel.

Set in the Depression-era Deep South, To Kill a Mockingbird is told through the eyes of Scout, a 6-year-old girl. Her sense of right and wrong is shaken when lawyer Atticus Finch — Scout’s father — fails to secure an acquittal for Tom Robinson, a Black man wrongfully accused of sexual assault and killed before he has a chance to appeal. Bob Ewell, one of Robinson’s accusers, vows revenge on Atticus and ambushes Scout while she’s returning from school dressed as a ham (don’t worry, it makes sense in the book).

Scout and her brother are saved by Boo Radley, a recluse and the subject of a ghoulish local legend, who kills Ewell in the process. Scout suddenly sees Radley as a human being and realizes that her previous prejudice toward him was unfair. She also backs up Heck Tate’s decision to report Bob Ewell’s death as an accident to spare the already-taunted Boo the publicity of a trial.

These actions and realizations show Scout acquiring a more “adult” and complete moral perspective. This includes the recognition that life consists of experiences with both “good” and “evil” and underlines the core message that people can choose to live consciously without becoming cynical or losing hope in human kindness.

4 tips to write a dénouement

If your story is drawing toward a close and you need help writing those final scenes, read on for a few essential tips to make your dénouement a valuable piece of the narrative.

🤔 Not sure where to start? Check out our step-by-step guide to writing a novel.

1. Hit the right emotional tone

A good dénouement can take a more reflective or somber tone if that’s what your story calls for, but it shouldn’t feel completely out of pace with the rest of the narrative. If you’re writing in the first person, make sure that the narrator keeps their unique voice. If you’re writing in the third person, don’t zoom out so far that your reader feels distant from the characters they’ve come to love.

The right tone will depend on the content of your story’s ending and the events that have led up to it, but the most important thing is to stay consistent with the rest of the book. Don’t end with a teary goodbye from a cold protagonist or a matter-of-fact account of tragedy — these tone imbalances will confuse your readers and leave them unsatisfied with your story.

In most cases, your characters should demonstrate some emotional response at the end of the story. They’ve dealt with conflict and seen themselves change, and their lives are probably very different by the end of the story. If your characters have no feelings about any of this, they won’t feel very convincing. If your protagonist doesn’t usually spill their feelings to the reader, show how they feel with action or dialogue.

2. Mind your pacing

After the protagonist addresses their main problem in the climax, most stories slow down to invite the reader to take a breath and reflect on what has happened. If your fast-paced story ends with a fast-paced dénouement, the reader will finish it without having a chance to recognize the changes that have occurred and their implications for the characters.

Instead of leaving your readers feeling frantic, control your pacing in the dénouement to give the story room to breathe. Like a rollercoaster sliding back into the platform after its exciting loops and turns, the dénouement gives the reader a few moments to catch their breath and collect themselves before closing the book and rejoining the real world. It’s a chance for readers and characters to reflect on what just happened, now that the peril has been defused.

Make the most of this concluding act by focusing on clarity and purpose, and don’t worry about maintaining the momentum that your story has built up.

3. Decide between explicit and implicit dénouement

Now that we’re clear on what a dénouement is, we can start to look at the different kinds of endings. On the broadest level, all dénouements lie somewhere on a spectrum between implicit and explicit.

The more explicit approach resolves the story’s loose ends or themes through actions or statements, sometimes even stating the “lesson” outright. This kind of ending leaves no questions or potential for confusion in the narrative. Explicit dénouement often occurs in fables, myths, and children’s books.

Implicit dénouements, on the other hand, rely on suggestion, symbolism, or leave the resolution up to the reader’s interpretation. Attentive readers might come away with multiple theories about what became of the characters. Implicit dénouement is more common in literary fiction and short stories.

Of course, your dénouement will probably fall somewhere between the two, making some details clear and leaving others up to the reader’s imagination. But regardless of how much you leave unsaid, you should be aware of common mistakes to avoid.

4. Avoid common pitfalls

A strong dénouement should feel like a natural resolution, not an afterthought. But many writers rush this crucial moment or make it feel unnatural by over-explaining. On one end, some writers make the mistake of tying every loose end into a perfect bow, leaving nothing for the reader to think about.

On the other end, some writers don’t explain enough, leaving readers confused and unsatisfied. Be sure to answer any questions that the reader may not be able to interpret from the action, and avoid unforeshadowed cliffhangers if you won’t be back with a sequel.

Another common pitfall is letting the denouement drag on too long, diminishing the impact of the climax. Keep your ending concise and focused, addressing the details that truly matter without explaining every last detail.

Finally, make sure you know the difference between a dénouement and an epilogue. The former is a required conclusion, while the latter is an optional chapter following the story that offers a peek into the characters' future.

And now, having seen the purpose a dénouement can serve in a story, we reach this post’s final, dying moments. Should we reflect on what we’ve learned about the topic? Maybe we’ll give you, gentle reader, a few moments to consider what you want to learn next. Or maybe we’ll leave you on an unsatisfying —

1 response

Stan Allen says:

23/06/2018 – 13:20

I wrote a short story for class work, while in college. The professor liked the story until the end. She stated that the ending was very weak, but couldn't tell me how to strengthen it. Thank you Reedsy for teaching me how to write the ending to a story.