Posted on Oct 26, 2021

5 Writing Techniques Every Writer Should Try on for Size

Tom Bromley

Author, editor, tutor, and bestselling ghostwriter. Tom Bromley is the head of learning at Reedsy, where he has created their acclaimed course, 'How to Write a Novel.'

View profile →Looking for some fresh writing techniques to build your skills or help you push through a writing slump? Here are 5 techniques that you can apply to any piece of fiction you’re working on. Why not try them on for size and see which ones fit!

1. Keeping the narrative grounded in action

When we think of ‘good writing,’ many of us imagine florid prose that lifts the soul and rises to the level of poetry. But, while we all love a stunning turn of phrase, this approach often leads to writing that isn’t anchored in the moment — that feels baggy, slow, and directionless. To keep your writing engaging and immediate, bear these two basic writing rules in mind.

Show, Don’t Tell

Whenever you feel the urge to describe something, find a way to do this through action. For example, if you were describing a character’s clothes, you could write:

Norah was cold. She wore an ankle-length fur coat with three golden buttons.

However, taking these two sentences to describe Norah’s coat creates five seconds during which the reader is taken out of the narrative. Instead, you could keep the action going by using the show, don’t tell technique:

Norah shivered. As she strode across the Stortorvet, she pulled up the collar of her floor-length fur coat, scrabbling to fasten its three shining gold buttons.

In this second version, we get the same information but, instead of a static mental image of a coat, we can also see the action of the scene. By turning your descriptions into actions, you can help keep the story moving. After all, when people read your book, they should be thinking what happens next?, not I wonder what this looks like.

FREE COURSE

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

Avoid passive voice, embrace active voice

The best way to describe passive and active voice is with a couple of examples:

Passive: I was hurt by his comments.

Active: His comments hurt me.

Passive: The boy scouts were inspired by the astronaut’s bravery

Active: The astronaut’s bravery inspired the boy scouts.

Writing in passive voice is often baggier: you use more words to express the same idea. It’s not particularly efficient. Not only that, passive voice also creates an awkward sense of distance between the characters involved in an action and the action itself. As ‘good practice’, aim to write actively for extra impact and engagement.

🚨 For more on this topic, check out our post on passive vs active voice 🚨

2. Activating the senses

One writing technique that can breathe new life into your work is focusing on the oft-neglected senses. Readers are used to knowing how things look and sound (“he had dark, beady eyes like a hawk; his voice was deep and peppy like a tuba in an oompah band”) but you can often add greater dimension to your writing by evoking smells, tastes, and tactile sensations.

Smell

We rarely mention how something smells unless it’s exceptionally pleasant or foul — but our noses can remember things our eyes have long forgotten. In writing, a carefully invoked smell can summon a reader’s own sense-memory: the smell of freshly buttered popcorn can take you to the lobby of a movie theater; a whiff of bodily fluids masked by disinfectant can transport you to a hospital.

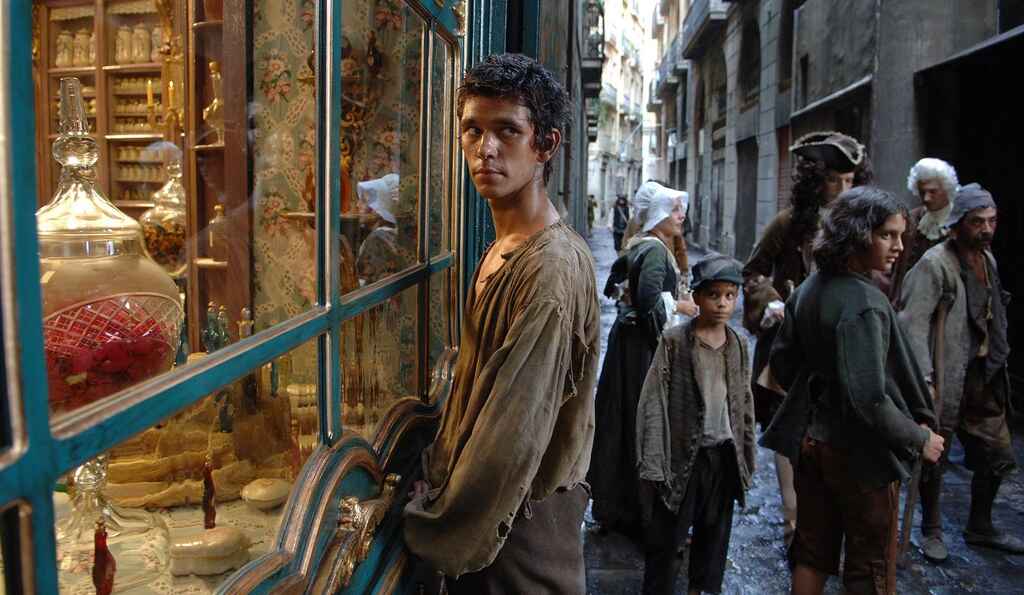

Example: Perfume by Patrick Suskind

In the period of which we speak, there reigned in the cities a stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots.

Taste

Like smell, tastes can have the effect of transporting the reader. Famously, in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, our narrator savors a freshly baked madeleine that unlocks a trove of childhood memories. In much the same way, you can tap into your reader’s shared experience of taste — both delicious and repulsive — to evoke a sensory response that draws them into your character’s headspace.

Example: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler

“Wow,” I said. And I meant it. I had never thought of a tomato as a fruit — the ones I had known were mostly white in the center and rock hard. But this was so luscious, so tart I thought it victorious. So — some tomatoes tasted like water, and some tasted like summer lightning.”

Tactile Imagery

Writing using the sense of touch is about much more than describing the feeling of sand through your fingers or a silk scarf on your shoulders. Though textures are crucial to building a full descriptive picture, touch also encompasses sensations we usually think of as beneath the skin, like sweltering in the heat, prickling with fear, or writhing in agony. Get it right, and tactile imagery can move readers to have a physical experience that’s completely immersive.

Example: Life of Pi by Yann Martel

“When the heat was unbearable I took a bucket and poured sea water on myself; sometimes the water was so warm it felt like syrup.”

3. Choosing a unique viewpoint

The underlying action of any scene can be presented in countless ways, depending on who’s observing it. Suppose in your story a doctor is examining their patient. First, let’s describe it from the doctor’s point of view:

Dr Hartmann slid the stethoscope across Ronny’s chest — a safecracker listening for one of a thousand possible clues that would unlock her patient’s condition.

And once again from the patient’s perspective:

Ronny winced as the cold steel of the stethoscope ran over his sternum. The doctor’s head was cocked at an angle, eyes vacantly fixed in the middle distance.

In both versions, the action of the scene is identical, but the reader’s impression of the doctor completely changes depending on the viewpoint. In the first, the doctor is a cool professional; in the second, they’re inscrutable — a dispassionate mechanic going through the motions.

Before you draft any book, chapter, or scene, you should always ask yourself, whose story is this, and whose eyes should we see it through? In most modern narratives, the viewpoint character and the protagonist are one and the same — but there are plenty of great reasons to choose another viewpoint character (whether that’s for a single chapter or the entire book).

🚨 Want to learn more? Check out our complete guide to point of view! 🚨

Lend your protagonist an air of mystery

Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is famously told from the POV of Nick Carraway, who recollects the summer he moved to New York and befriended Jay Gatsby. A mysterious millionaire on the Long Island social scene, Gatsby’s secrets and intentions are gradually revealed to the reader as Nick tells his friend’s story.

For the most part incidental to the events of the novel, Nick is an outsider and a voyeur — yet, as a character himself, his bias filters and colors our perception of the other characters and their actions. Knowing this, the reader never truly feels that they understand Gatsby. This lends an air of mystery to the protagonist and throws a dark veil over the narrative — one which would dissolve if Gatsby himself were the POV character.

Ease your readers into a new world

Quite often, viewpoint characters are designed to be “reader proxies”: characters with whom readers will naturally identify. This can be useful if your story takes place in a setting that most people are unfamiliar with.

For example, if your story is set in the secretive environment of a Navy submarine, you might wish to tell it from the viewpoint of a new recruit. Aligning the viewpoint character with the reader can help ease your audience into an unfamiliar world by giving you plenty of opportunities to add expository information into your story in an engaging way, such as through dialogue or a special device like a manual.

Throw readers in at the deep end

That said, good writing isn’t always about making things easy. Readers are pretty adept at playing catch-up, so often enjoy being plunged into a new environment rather than led from the safety of the sidelines.

Sometimes, a viewpoint character who’s thoroughly embedded in their community or a veteran in their industry, for example, can provide an illuminating perspective — even if it means initially throwing readers in at the deep end.

What’s great about these characters is that their insight allows you to observe the shifts, nuances, and finer details of your setting. This is particularly useful when your story explores a community whose secrets are only known to insiders — like a high school or the Hollywood elite.

Provide an illuminating point of contrast

Though Nick Carraway is an outsider in that he isn’t central to the events of the novel, he isn’t a true outsider because he doesn’t think or behave so differently from the other characters. If Fitzgerald had wanted to create an obvious contrast between the narrator and the protagonist, he might have had the mechanic George Wilson narrate The Great Gatsby — a POV that would have elicited a very different response from readers.

For a POV character to provide a point of contrast, they don’t have to exist in an entirely separate circle. If you’re writing a historical romance set in a society governed by convention, for example, a viewpoint character who recognizes the snobbery of the company they keep (think Lizzie Bennet from Pride and Prejudice) can prevent the reader from becoming too enmeshed in its way of thinking — adding an element of social commentary or even satire to your writing.

4. Experimenting with different forms

Writers choose all sorts of different ways to deliver a narrative — poems, screenplays, novels, essays — but no matter what business you’re in, crossing boundaries and experimenting with the formal structure of your writing is always a great way to keep things fresh.

Though a medium like a letter or a newspaper clipping may seem restrictive — due to the added constraints of formatting, and perhaps tone — experimenting with form is a writing technique that has the potential to unlock boundless creativity.

Epistolary narratives

In an epistolary narrative, the story is told in the form of letters. It can be written by a single character to someone whose responses aren’t heard or sent between two or more characters, whose points of view are all represented.

The effect of an epistolary narrative is an intimate kind of voyeurism — because of the style’s inherent authenticity, we feel as though we’re peering into the personal life of the letter-writer. This brings us closer to the character and creates a sort of conspiratorial relationship.

One book from classic literature that does this particularly well is Dangerous Liaisons. Composed of letters passed between two former lovers, the epistolary form transforms the reader into an accomplice in their games of seduction.

Emails and instant messaging

The way we communicate with each other is constantly changing — indeed, most of the letters we receive these days go straight in the trash. So some more recent epistolary narratives reflect this change by swapping letters out for emails.

The email exchanges scattered throughout Sally Rooney’s novels work as letters would to bring us closer to the characters and give us insight into their relationships — we learn what they choose to share with the people in their lives, and what they don’t.

Instant messaging can feel even more authentic to a modern audience. In the 2019 novel Queenie, the protagonist assembles a trio of friends in a group chat from which we’re given regular snippets. Not only does this form sharpen the voices of the characters, but the messages feel so familiar to the modern reader that the group dynamic is instantly credible.

Logs and other formal documents

When experimenting with form, don’t be afraid to think outside the box. As long as it helps to tell the story, anything is valid — be it a doctor’s report, a questionnaire, an interrogation, or a ship’s log.

You might write your whole narrative in one form, as Joyce Carol Oates does in “...& Answers”. Structured like a therapy session, Oates puts her twist on a question and answer dialogue by making it one-sided: the reader is left to speculate about what the other person in the conversation is saying.

Featuring a mix of forms in your writing can also be an interesting way to experiment. Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for example, relies on newspaper clippings, a ship's log, a medical journal, telegrams, and diary entries to build a cumulative picture of events. His use of form lends credence to an otherwise improbable story.

5. Compressing everything into a short timespan

No matter which form you choose from your arsenal, something every writer dreads is a loose and meandering middle: a narrative that loses tension. To avoid this common faux pas, heed the advice of two short fiction masters, Ernest Hemingway and Kurt Vonnegut, and restrict your narrative to as short a timeframe as possible. This gold label writing technique should help you add momentum to repetitive and rudderless work.

Get in late, leave early

Kurt Vonnegut's golden rule of writing is that every story should start as close to the end as possible. So as not to cut out the meatiest part of the narrative, you might interpret this to mean in the middle of the action — or in medias res. By skipping over the inciting incident, and folding any necessary exposition into the rising action, you cut down your story’s timespan and keep your writing snappy.

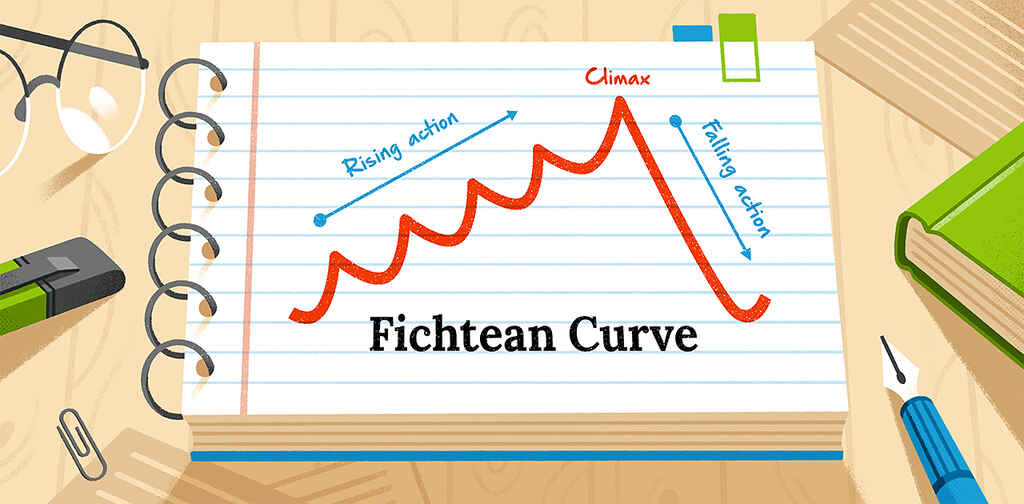

Another story structure that kicks off with rising action is The Fichtean Curve. This structure sees the protagonist come up against several obstacles in anticipation of the highest story point, the climax; exposition is seamlessly folded into the action, and everything is left unresolved until the very end — when you tie things up and make a swift exit.

This tension-packed approach works particularly well for mysteries and thrillers, but if your writing tends to be lighter on plot, this writing technique might still be a fit. Literary fiction that focuses on mood, attributes importance to the mundane, or dives into a character’s psyche might benefit from the “vignette” approach. A concise yet evocative account of a moment in time is often the best way to capture a person, event, or place in a piece that lacks plot.

Hemingway’s iceberg theory

Writers who try to restrict their word count or timeframe will soon find that a lot of what they previously would have said upfront, now needs to be implied. The idea that the reader might have to infer some of your story’s details is exactly what Hemingway was getting at with his “Iceberg Theory” — which posits that you should only provide readers with the most essential element of your narrative.

While it’s great to know the ins and outs of your characters’ elaborate backstories, and have far-reaching plans for their futures, in this current work readers only need to know the here and now. So try to keep most of what you know about a character’s past and future to yourself, including only what’s directly relevant. By doing so, not only do you keep some plot in the bank for a sequel, you also hold the interest of your readers by drip-feeding insights.

🚨 To learn how to turn unused plot into its own narrative, check out our post on how to write a series! 🚨

And with that, we’re going to round off this list. Hopefully, one of those five writing techniques will help you to refresh your prose, and maybe even perfect a long-languishing piece. If all goes well, then you might end up with something you’d like to publish!

Be sure to check out our tips to edit your own writing, then take a look at these publishing resources: