Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

What is the Narrative Arc? A Guide to Storytelling Through Story Structure

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Has anyone ever told you that your narrative arc was too weak? Too complex? Or not complex enough?

Universal to both fiction and nonfiction (particularly certain types of nonfiction), the narrative arc (also called the “story arc”) refers to the structure and shape of a story. This arc is made up of the events in your story — the sequence of occurrences in the plot — and determines the peaks and plateaus that set the pace. A good arc is vital if you want to engage your readers from start to finish, and deliver a satisfying conclusion.

What is a narrative arc?

Narrative arc, also known as a "story arc" or "dramatic arc," is the framework that gives structure to a story, including exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. It guides the flow of events, creates compelling conflict, and provides a clear and engaging path for a story.

You may already be familiar with one classic example of the story arc: boy meets girl, boy fails girl, boy gets girl again. This may sound oversimplified, and it is. Adding complexity to a basic story arc is part of what differentiates one story from another, even when they’re ostensibly dealing with the same ideas.

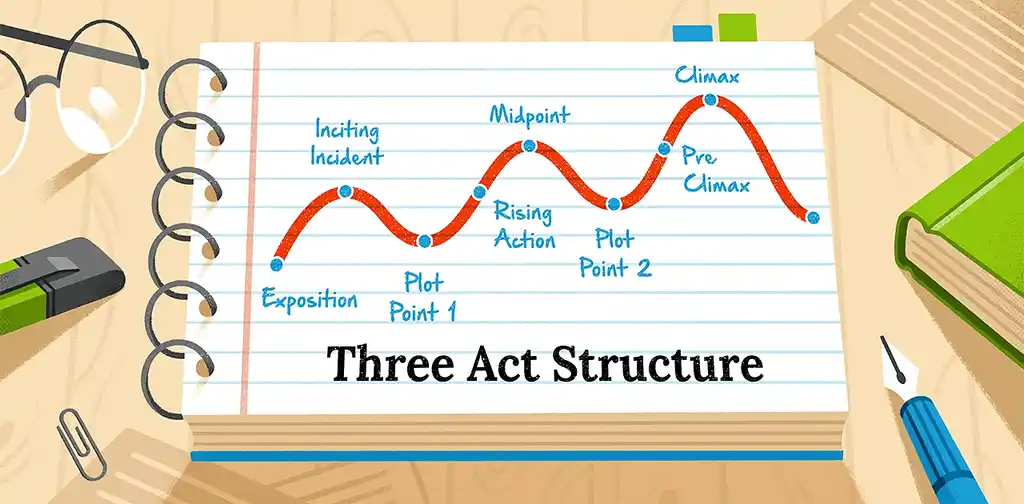

It’s sometimes useful to think about the story arc as though you’re setting up a simple dramatic play. Ultimately, you’ve got three acts to tell your story.

- In Act One, you set the scene and introduce your audience to the characters, the setting, and the tense seeds of conflict.

- In Act Two, your characters grow and change in response to conflicts and circumstances. They set about trying to resolve the Big Problem. Usually, the conflict will escalate to a the climax.

- In Act Three, characters resolve the Big Problem and the story ends.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

What’s the difference between a narrative arc and a plot?

While the plot is comprised of the individual events that make up your story, your story arc is the sequence of those events. Imagine every scene of your novel summarized on notecards: the entire stack of cards is your plot, but the order in which you lay them out is your story arc.

Thinking about your arc is essential around this point. What if your Scene 1 notecard actually belongs in the denouement? What if you have too many scenes based on internal conflict in a row (leaving the external conflict to wither)? Carefully ordering your plot into a cohesive story arc helps readers navigate your story, and sets expectations that you can either satisfy or disrupt.

If the plot is the skeleton of your story, the narrative arc is the spine. It’s the central through-line marking the plot’s progress from beginning to end.

How about the character arc?

The narrative arc is to the story what the character arc is to a character. It involves the plot on a grand scale, and a character arc charts the inner journey of a character over the course of the plot.

Another straightforward distinction: while the story arc is external, the character arc is internal, and each main (and sometimes secondary) character will go through an individual arc.

Still, narrative and character arcs are part of a symbiotic relationship. Each plot point in the story arc should bring your characters closer to, or further from, their goals and desires. The circumstances and conflicts your characters face are part of the arc, but the way characters meet challenges and change as a result is “character arc” territory.

Pro tip: Interested in writing a solid character arc? Learn about what defines a dynamic character in this piece.

How to structure a narrative arc

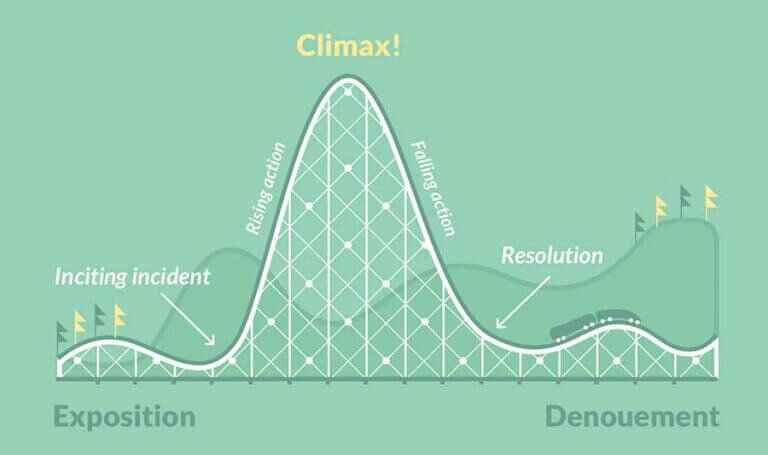

Remember what we said about the three acts that make up a story arc? If you try to visualize the progression of action in your mind, you may see something that builds up and falls as so:

That’s right . . . a pyramid. (One that's set upon a roller coaster, for your viewing pleasure.)

Free course: Mastering the 3-Act Structure

Learn the essential elements of story structure with this online course. Get started now.

Freytag’s Pyramid

In 1863, Gustav Freytag, a 19th-century German novelist, used a pyramid to study common patterns in stories’ plots. He put forward the idea that every arc goes through five dramatic stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Freytag’s Pyramid is a useful tool that reveals the structure of many stories, so it’s the framework we’ll be using in the next few sections. Feel free to use the diagram above as a reference as you follow along, or skip to your preferred stage below.

Exposition

Rising Action

Climax

Falling Action

Denouement

Exposition

The de-facto introduction to your book, the exposition is Act One of the story arc. You’re setting the table in the exposition: opening the story, bringing out your characters, setting up the seeds of conflict, and imparting just enough background information to keep the reader clued in on what’s occurring in the story.

Here’s a brief overview of what else the reader should be able to extract from the exposition of your story (which, incidentally, ties neatly into the 5 Ws):

- The characters. Who’s in the cast of characters? How can you differentiate among them?

- The setting. Where does your story take place? Don’t forget that setting includes time — when does your story take place? What time period?

- The mood. How will you calibrate the mood of the novel in the exposition? A romance that suddenly goes sideways due to an alien invasion is going to confuse readers and cloud your book's genre classification.

The size of the exposition depends on your book. The Count of Monte Cristo takes many thousands of words to set the stage, while P.G. Wodehouse wastes no time galloping past the exposition. Here's a post on chapter length if you'd like to learn more about pacing your work.

A word of caution: remember the golden rule of “Show, Don't Tell” — and don’t mistake “exposition” for “info dump.” Even while Tolkien is busy introducing the reader to an enormous cast of dwarves in The Hobbit, there’s a booming party going on and poor Bilbo’s scrambling to serve tea!

Readers will be interested in background information only when it doesn’t distract or detract from the plot. You must balance action and information if you want them to continue flipping the pages.

Rising Action

What’s a good story without a few (or more) wrinkles?

Usually, the rising action is prompted by a key trigger (also known as the inciting incident), which is what says to the reader, “Here we go.” It’s the moment Romeo sees Juliet, or it’s the split second in which Katniss’s sister, Prim, is picked during the reaping. Whatever the circumstances, the key trigger is the event that rolls the dice and causes a series of events to escalate, setting the rest of the story in motion.

As your exposition already set up your characters and conflict, it’s now the job of the rising action to:

- Develop the characters while allowing relationships between characters to deepen.

- Escalate the conflict and amp up tension.

In Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, everything that occurs after Hercule Poirot steps foot onto the train — up until the murder of R — constitutes the story’s rising action. In the book, this stage’s function becomes twofold: not only does it strengthen the suspense on the train, but the sequence of events also starts revealing the cast of suspects’ relationships and motives to the reader. How your characters respond based on what they want or need will speak volumes about them.

Climax

A good climax will build upon everything earlier — the storylines, motives, character arcs — and package it all together. It’s both the moment of truth for the protagonist (the peak of the character arc) and the event to which the plot’s built up (the peak of the arc). When the outer and inner journeys come together and click, you know you’ve got the beginnings of a winning climax.

FREE OUTLINING APP

Reedsy Studio

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

On the flip side, a bad climax is the easiest way for a reader to feel cheated and chuck your book at the wall. They’ll use your book as tissue paper in the future, or — worse! — never pick a book of yours up again. So the climax is one of the most important parts of your story arc. While it’s the beginning that sells ‘this novel,’ it’s the climax that sells ‘the next’ novel.

Falling Action

Okay, so you’ve gone and banged out a climax that knocks the reader right out of the park. What next? Your job definitely isn’t over yet, because the story can’t just grind to a stop. (FYI, that would make it every reader’s Public Enemy #1: the cliffhanger.)

Instead, you can follow this old axiom: what goes up must come down.

Let’s say that Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone closes up shop right when Harry passes out after defeating Quirrell. But we need to see Harry wake up in the Infirmary and chat it out with Dumbledore; to feel satisfied, we need to see Dumbledore award Neville Longbottom the 10 House points that win Gryffindor the House Cup. In much the same way, you can show the reader the fruits of the protagonist’s toils. Think of this stage as the bridge between the climax and the resolution. How do you get your characters from the climax to Happily Ever After™?

Let’s say that Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone closes up shop right when Harry passes out after defeating Quirrell. But we need to see Harry wake up in the Infirmary and chat it out with Dumbledore; to feel satisfied, we need to see Dumbledore award Neville Longbottom the 10 House points that win Gryffindor the House Cup. In much the same way, you can show the reader the fruits of the protagonist’s toils. Think of this stage as the bridge between the climax and the resolution. How do you get your characters from the climax to Happily Ever After™?

Here are a few things to keep in mind during this stage of the story arc:

- Your characters shouldn’t stop moving just because you’ve checked off the climax. The word “action” does exist in “falling action”; make it count.

- Usually, this is the stage where authors start resolving any remaining subplots and mini-conflicts. In Shakespeare’s comedies, this is the stage where everyone merrily pairs off with the right partner. Use this space to tie up any and all dangling threads.

Denouement

And after all that? Well, you’ve made it to the denouement. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy are engaged. Bilbo returns to Bag End. Huck Finn settles down with Aunt Sally to be “sivilized.” Ishmael is rescued from the sea. Everywhere, readers breathe a collective sigh of relief.

Also called the resolution, the denouement is just a fancy way of saying that the book is now going to wrap up.

For an example of this stage’s function, take the old-fashioned detective novel. In the detective denouement, the detective gathers everyone in a room and reveals the whodunnit, explaining everything. All questions are resolved, all ends are wrapped up — and the reader can shut your book with peace of mind. Congratulations! That’s the whole arc business done and dusted. Isn’t it?

Well, sometimes. That begs the question of. . .

Does Freytag’s Pyramid work with every story?

History is dotted with novels that bucked the trend. On the Road possesses virtually no narrative arc while To Kill a Mockingbird arguably possesses two arcs (the arcs of Tom Robinson and Boo Radley). The Trial builds up to a complete anti-climax in the place of a climax; meanwhile, Catcher in the Rye casually drops a sentence in the denouement about (spoiler warning) Holden going to a mental institution before the book ends, abruptly.

All this is to say, there’s plenty of room within the arc to explore and experiment. Disrupting reader expectations isn’t always a bad thing, but successfully straying from the expected course requires comprehensive understanding of the traditional story arc. After all, you can’t break what you can’t build.

Another item of note: although the popular five-act structure of Freytag’s Pyramid does capture the chronology of many books’ plots, be aware that some authors use a three-act structure. One significant change that will result deals with the placement of your climax. Learn more about the three-act structure in our article here.

Putting it all together

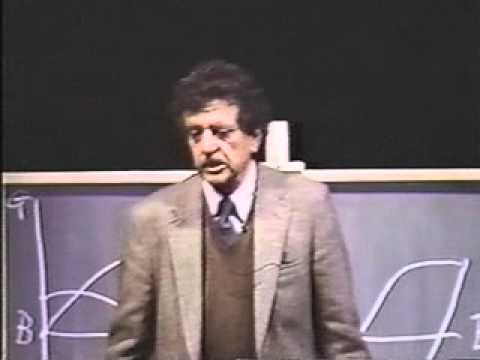

Here’s a parting gift before you go: a video from Kurt Vonnegut, describing the shapes of stories.

In the end, that’s what a strong story arc does: it gives a story shape. For alternative story structures, check out:

- The Hero's Journey – in which the main character goes on a quest;

- Dan Harmon's Story Circle – in which the character(s) eventually return home having changed; or

- The Fichtean Curve – a slightly more “intense” version of the classic structure, in which the action begins immediately and escalates rapidly.

To add more dimensions to your story, you can experiment with subplots. Subplots function as mini-arcs, though they should always aim to contribute to the main arc in some way.

Sort out your story arc — experiment with it! — and your story won’t be a formless, blobby thing. It’ll gain a spine and new readers.

And, of course, if you’re struggling to create a compelling narrative arc, a professional developmental editor will be able to come to the rescue and spot deficiencies.

Hire an amazing developmental editor on Reedsy

Helen L.

Available to hire

Literary Agent and Developmental Editor. I represent incredible authors at Ki Agency. My editorial focus is on Fantasy, Sci Fi and Romance.

Paul H.

Available to hire

I have a PhD in philosophy and two decades' experience in editing humanities manuscripts for university presses and independent authors!

Dan H.

Available to hire

Professional editor of SFF/Horror. Have worked with bestselling authors Shauna Lawless, Gemma Amor, Stacey McEwan. (No AI please.)

6 responses

Kristen Steele says:

10/09/2017 – 17:29

"While it’s the beginning that sells ‘this novel,’ it’s the climax that sells ‘the next’ novel." Couldn't agree with this more! Readers invest a lot of time in a book and a disappointing climax is a turn off.

Paul McGaughey says:

19/11/2017 – 20:29

"[Freytag] put forward the idea that every narrative arc goes through six dramatic stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution." I'm only seeing five here, is there a stage missing in this post?

↪️ Gerald replied:

11/02/2018 – 13:41

In one place, they miss "denouement" and in another, they miss "resolution".

↪️ Reedsy replied:

12/02/2018 – 04:50

Great eyes, Paul! There are indeed only five dramatic stages: the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. The "six" was a typo. Thanks for the catch — we've since amended the post.

Tomas Pueyo says:

10/03/2018 – 06:25

Great, thorough article on storytelling. One thing that always bothered me about traditional storytelling structure though is how different authors think there are different structures of storytelling. This TEDx covers that well, and proposes a solution to that conundrum. Hope you enjoy! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUT6GQveD0E

↪️ sharon harrison replied:

03/02/2020 – 09:49

lol