Posted on Mar 27, 2023

How to Write a Prologue Readers Won't Skip (with Examples)

Tom Bromley

Author, editor, tutor, and bestselling ghostwriter. Tom Bromley is the head of learning at Reedsy, where he has created their acclaimed course, 'How to Write a Novel.'

View profile →A prologue is the introduction to a book. Specifically, it's the part of the story that comes before the beginning of the main narrative. A good prologue will set the scene for elements that may become important later in the book, provide context, hint at themes, and pull readers in without info-dumping or giving the game away.

Many writers are intimidated at the prospect of writing one, but there are a few simple rules to follow that can keep your prologue on the right track.

Here are 5 rules for writing a prologue for a book:

For more detail on how to write a great prologue, plus examples of prologues done right — or wrong — to illustrate each point, read on.

1. Include a prologue for the right reasons

Writers often insert a prologue into their book to prop up what they think is a flat or boring first chapter. But a prologue shouldn’t be a substitute for an interesting first chapter. If anything, following a high-stake prologue with a weak, pedestrian chapter one can leave readers feeling let down.

However, there are other, great reasons to employ a prologue. These include:

- Showing a moment near the book’s climax to create tension in medias res

- Introducing a character or location not present in the first chapter to create tension

- Establishing atmosphere or a central theme to pull your reader further into the story

We’ll go into these below, but let’s pause for a moment to consider what you can do if you feel your prologue doesn’t really serve a purpose. Scrapping it entirely and working on your opening scene instead is always an option.

Ask yourself what instinct led you to add a prologue, and learn from yourself: perhaps you were sensing that a main plot twist comes too late in the book, and you were missing out on a chance to engage your readers early on. Try to pin down what you wanted your prologue to do, and if you can’t, discuss your concerns with your developmental editor, who’ll be able to weigh in on whether your book really needs one or not.

Hire an expert editor

Paul H.

Available to hire

I have a PhD in philosophy and two decades' experience in editing humanities manuscripts for university presses and independent authors!

Helen L.

Available to hire

Literary Agent and Developmental Editor. I represent incredible authors at Ki Agency. My editorial focus is on Fantasy, Sci Fi and Romance.

Ed W.

Available to hire

I'm an experienced proofreader whose clients include University of Washington Press, Mountaineers Books, and The Yale Review.

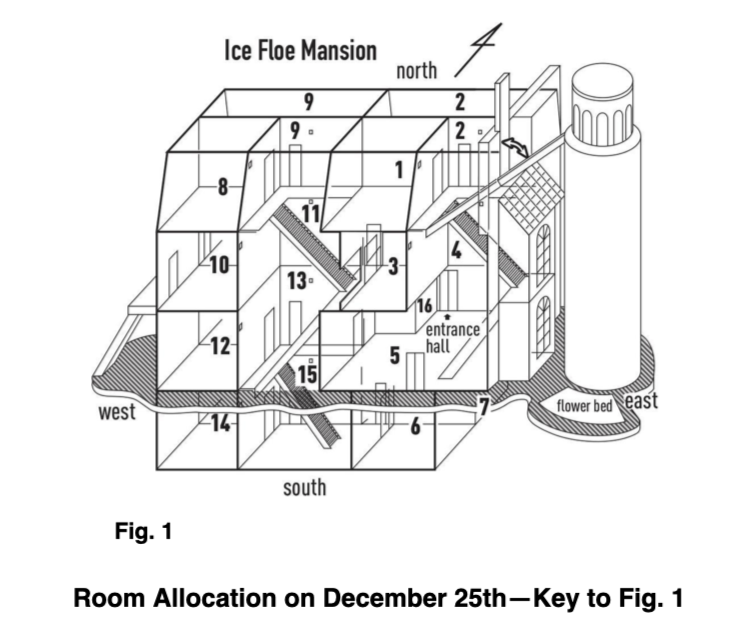

Example: Murder in the Crooked House by Soji Shimada

Murder in the Crooked House by Soji Shimada is a classic locked-room mystery, so the setting of the Crooked House (an extremely bizarre maze of a house) is key to the crime and the plot.

Its prologue introduces the concept of erratic, bonkers buildings in Europe, then transports readers to Japan, explaining that oddball buildings are rare there — but there is one house we ought to know about, the Crooked House. It then describes this house in some detail. It provides a sketch of the building, effectively laying down the rules for the mystery game about to unfold. Armed with a clear sense of the building’s layout, the reader is now ready to jump in and appreciate the puzzle-like structure of this novel.

Murder in the Crooked House is a strong example of a prologue that is completely necessary to enjoy the following story. It has been included for the right reasons; it provides essential context and worldbuilding and establishes the story's tone.

FREE RESOURCE

The Ultimate Worldbuilding Template

130 questions to help create a world readers want to visit again and again.

If you’re certain that you want to include a prologue, and are doing so for the right reasons, then read on for more tips on writing them well.

2. Center your prologue on character action

Even if your prologue needs to relay information about your book's world, it should always focus on character action. This will help you draw readers into the story, instead of making them wade through expository housekeeping. One way to do that is to ensure something happens in your prologue.

While the obvious choice may be to center your prologue around a main character, many prologues focus on a peripheral figure. This allows the book to introduce a new perspective that might not be easily found in the main body of your story.

Perhaps your prologue’s narrator is a foil for your protagonist, providing context or highlighting their more unusual qualities. Maybe your prologue is written from your antagonist's POV, building conflict right from the outset. Or maybe this new character is not immediately recognizable to the reader: a mystery narrator (whose identity is later revealed) can be most intriguing.

Whichever character you choose to frame your prologue, try and focus on them doing rather than thinking to create forward momentum.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

Example: A Game of Thrones by George RR Martin

The prologue to A Game of Thrones establishes the tone and world of the story, especially through its use of character action. It doesn't feature any of the series' main characters but, instead, a band of Night’s Watch rangers. As they track a group of wildlings beyond the north wall, they encounter the undead Others, men who have long been considered extinct. The group leader is killed (only to rise again and slay his comrade as an Other), while the third man flees.

This action-packed prologue works on multiple levels. The choice of point of view, following characters who will never feature again in any meaningful way, allows us a unique perspective on the story's world. It becomes immediately clear to the readers that the Others exist, which our main characters don’t yet know, in a classic example of suspenseful dramatic irony.

The heavy focus on action also establishes the tone of the novel. While the following chapters focus on courtly intrigue and politics, the prologue creates an expectation for violence, bloodshed, and magic, showing readers what they’re in for.

Q: In what circumstances should an author consider adding a prologue to their book?

Suggested answer

A good prologue will provide intrigue and spark curiosity. It whets the reader's appetite and poses a question that the book will answer.

How does it do this? A good prologue is there to tease something that happens deeper in the novel that becomes clearer later on.

I don't think that prologues that tell something about the past are as effective. If there is something deep in the past that sheds light on the narrative, you want to save that to be revealed later on in the story. Giving it all away upfront defuses, rather than increases, narrative tension.

I would always caution against anything like a dream or some other kind of less-than-real moment as a prologue as it is very important that the reader is focussing on the right kinds of mystery (what is the secret of this story? what will be revealed?) and not on the wrong kinds of mystery (who is this? why am I hearing about this now? what's going on?).

You can find your prologue by picking a moment from deep inside the story that ticks some or all of these boxes: a moment of tension, a moment of misdirection, a gathering together of some of the themes of the novel, sensory details that will stick in the reader’s mind.

Play around with your own version of this to see how it affects the narrative.

Laura is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Agents often ask if the prologue is REALLY necessary. I’ve published books with and without, and I’ve found it to be a useful tool when it:

- Establishes genre. Sometimes, a story needs some setup before the genre really kicks in. For example—in Twilight, it’s more than halfway into the book that the promise of the premise (girl engaged by vampires by way of loving one) kicks in. So we get a passage that gives us a little taste of what’s to come.

- Will be a fun callback at a penultimate moment of the story, bringing things into focus in an exciting way

- Creates mystery and intrigue

- Sets a ticking clock. Sometimes, a prologue is a flash forward to a time in the near future, showing us danger to come and setting up suspense from the beginning. You’re telling the reader, “Everything may look nice in chapter 1, but in three days, we’ll be on the edge of a cliff.”

I’ve seen prologues get cut when their function is to add ambience or world building, character development, or when they are attempting but not succeeding at one of the above strategies. Often, a writer will have to explain why this prologue has to exist in this format and why this scene can’t be worked into the book otherwise.

Happy writing!

Wendy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Well, Prologues are tricky, as you obviously know from asking the question. First, readers and gatekeepers are not fond of them, and second, they sometimes feel like sidelines with separate stories and characters that were nonessential. This is because the only reason to adda. prologue is if you have a piece of the story to tell that is essential for readers to know to understand the rest of the story, whether right away or deeper in. Maybe an earlier event sets up circumstances that are key to the story (like how Superman got to Earth and why he has powers, to use a classic example), or maybe it sets up events on the world that take generations to come to a head but which are core to events in your story. Either way, the prologue should be full of conflict and action with a core character we quickly care about. Even if that core character is a predecessor to later characters, he or she must be someone we feel and root for. Never ever should your prologue be a history lecture or summary about events that took place before the story. Any of those which are essential can be told about through dialogue and narrative voice and so on as needed, and as needed only. History lesson prologues never ever work. They are the main reason prologues have gotten such a bad name.

Hope this answers your question. Best of luck!

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think prologues are most effective when used as a quick hook to lure the reader in—something action-packed and exciting. Other reasons might be to set up a larger fantasy/dystopian world where a brief primer might put the reader in the right frame of mind for the broad scope of the main text of the novel.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Here's a rough guide on whether you should consider adding or removing a prologue from your book:

- Is it too long and can it be shortened while retaining the same information?

- Does this prologue contain elements that are vital to the story?

- Does removing the prologue change the story in any way, good or bad?

If the answer to that last point is no, then that's a good sign that the prologue can likely be cut or doesn't need to be there. When deciding on whether to include a prologue or not, ask yourself: Can the information in this prologue be shown any other way somewhere else in the book? Is this prologue a sort of pre-writing exercise for me as the author to help me get into the world and characters, and can be cut later? And, as I evaluate, if I remove this prologue, what about the book and story changes?

Prologues can be a great and powerful way to get the story started, but like everything else in a novel it has to have a purpose to serve the story.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Speaking of creating expectations, let’s take a closer look at how prologues can emphasize core themes or images.

3. Focus on what you want readers to take away

Prologues are an opportunity to plant key themes or motifs. In our Game of Thrones example, the prologue sets the tone for what is to come and provides readers with a context for the body of the narrative. Focusing on key themes within the prologue also allows greater cohesion, marrying what could seem like an unrelated preamble with the rest of the story.

Hinting at the story’s underlying theme can also heighten curiosity and anticipation for what’s to come. Readers naturally want to understand the greater meaning of what they’ve been shown — and they assume all will be revealed later in the book. What you choose to highlight in your prologue will have significance in the minds of your readers, so choose your focus carefully.

Not every theme has to appear in your prologue — it’s sometimes best to simply focus on a key image that you can condense into the brief format of a prologue. Anyway, don’t sweat the first draft — if you’re using a writing app like Reedsy Studio, you can easily circle back to the beginning and amend your prologue’s focus later.

Example: What a Carve Up! by Jonathan Coe

Jonathan Coe’s What a Carve Up! uses its prologue to set up several thematic threads of the story. The book focuses on a biographer hired by the estranged eldest sister of an influential family to investigate them all. Each family member represents a tendril of Thatcher’s Britain, manipulating the worlds of journalism, art, politics, agriculture, and banking.

The prologue takes place at the family home in the 1940s and 60s, and details one mysterious death in the family (while hinting at another). It establishes the family’s treachery and murky underbelly, as well as the interpersonal conflict and suspicion that has ravaged the Winshaws for decades. It also introduces the mansion, which the family's next generation will be drawn back to in the grisly final act.

A violent ending may have come out of nowhere had the novel not had a prologue establishing the story’s overall tone, whereas the rest of the book has sections focusing on more grounded, real-world issues.

💡Thinking of writing a whodunit? Check out our guide on writing creepy and satisfying mysteries.

By hinting at what has come before, prologues are also able to create tension about what’s still to come.

4. Keep your foreshadowing subtle

Remember to pique your readers’ interest, not send their eyes rolling to the back of their heads. Heavy-handed foreshadowing runs the risk of spoiling the twists and turns that are to come, so ensure that any hints you do give aren't enough to deflate your readers’ sense of anticipation.

Ideally, your clues for what’s to come should be relatively cryptic: suggestive enough to establish your tone and create intrigue while compelling readers to keep moving forward. You don't want the clues to be so clear or straightforward as to make the rest of the story redundant.

Example: Eragon by Christopher Paolini

Christopher Paolini’s Eragon may have faced criticism for its occasionally complicated prose, but no one can criticize its intelligent use of its prologue. In it, the reader is introduced to creatures they don’t recognize, Urgals and a Shade, as they ambush a group of three elves transporting a mysterious pouch containing a sapphire. Two elves are killed, while the third — a woman — magicks away the gemstone before collapsing. Frustrated, the Shade rides away, leaving her there.

It’s a brief prologue that quickly does everything it needs to, establishing a world of magic and non-human creatures without losing time to explain who everyone is or what they’re doing there. What matters is the sapphire stone being saved from the clutches of these violent beings.

The reader knows this stone is no ordinary stone — it’s powerful, important, and sought-after by the bad guys of this world. Soon after, Eragon, the book’s protagonist, discovers this stone in Chapter 1.

He won’t know it, but the reader will immediately know he’s in danger. Nicely done, no?

Paolini accomplishes this efficiently and concisely without overwhelming readers with explanations. This, too, is a sign of a prologue wisely used.

5. Avoid inundating readers with an info-dump

There may be countless things about your world that you want to share with readers, but remember that this is their first taste of your book. You don’t want to overwhelm them with information. Many new (and experienced) writers) will feel the need to tell readers everything about the world of their book within the prologue, but this type of exposition usually leads to readers switching off, or, even worse, putting the book back on the shelf and buying something else. Instead, trust in your reader’s ability to wait for information and piece things together.

Go for a prologue that’s short and immersive — and as always, show, don’t tell! To prevent yourself from overwriting, keep in mind that creating a story world is a constant effort that the prologue can be a part of, not a substitute for.

FREE COURSE

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

Example: Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton

Jurassic Park is an unusual example in that the novel contains not one, but two prologues (albeit one is labeled an “introduction”). The contrast between these two prologues can be seen as a prologue done right, and a prologue gone wrong.

The first prologue, “The InGen Incident,” is heavy on exposition, reading like a short historical account of genetic engineering. While the chapter does hint at what is to come, an exploration of the ethical implications of bioengineering, it’s a pretty dry read.

The following prologue, more excitingly named “The Bite of the Raptor,” is a far more compelling starting point for the novel. It tells the story of a doctor treating a critically wounded construction worker whose injuries aren’t quite adding up.

While the official story is that he’s been hit by an earth mover, his clean wounds and intact bones suggest something else has happened, and before he dies, he mumbles the words “lo sa raptor.” As the doctor struggles to translate the dying man's words, the mystery of what is truly happening ramps up.

While the initial prologue is certainly relevant, it’s a little indulgent, giving us more information than we strictly need to begin the story that’s to come. The second prologue does a far better job of creating intrigue, kicking off the novel’s action effectively. Our advice? Readers can probably skip that first prologue altogether.

Whatever you do, make sure your prologue-related decisions are intentional and contribute something to your project. After all, every scene in a book should add something that would be missing if it was removed, and the same principle applies to prologues. Happy writing!