Blog • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Oct 17, 2025

How to Write a Book Proposal in 9 Steps

Loretta Bushell

Loretta is a writer at Reedsy who covers all things craft and publishing. A German-to-English translator, she specializes in content about literary translation and making a living as a freelancer.

View profile →Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Do you have a nonfiction book in the works and dream of securing a lucrative deal?

We have two words for you: book proposal.

In the nonfiction world, you secure agent representation and/or a book deal with a publisher (often before you even finish writing) by submitting a book proposal: a short document that pitches why your title is the next big thing. It's essentially a business plan, outlining the target audience and market viability of your book, as well as your qualifications as an author.

When successfully executed, a book proposal will convince an agent or publisher to invest in you and your goal: a published book. In this post, we’ll show you how to write a book proposal that stands out from the slush pile.

1. Know the key elements of a book proposal

The first step in nailing your pitch is to familiarize yourself with the key elements of a book proposal.

According to Reedsy ghostwriter Sally Collings, every good proposal will cover:

- What the book is about,

- Why it’s needed,

- Who it’s for, and

- Why you’re the ideal person to write it.

Above all, your proposal must show evidence of a need in the market. In other words: what is your unique premise? How will it benefit people who read it? Will readers care enough to buy it?

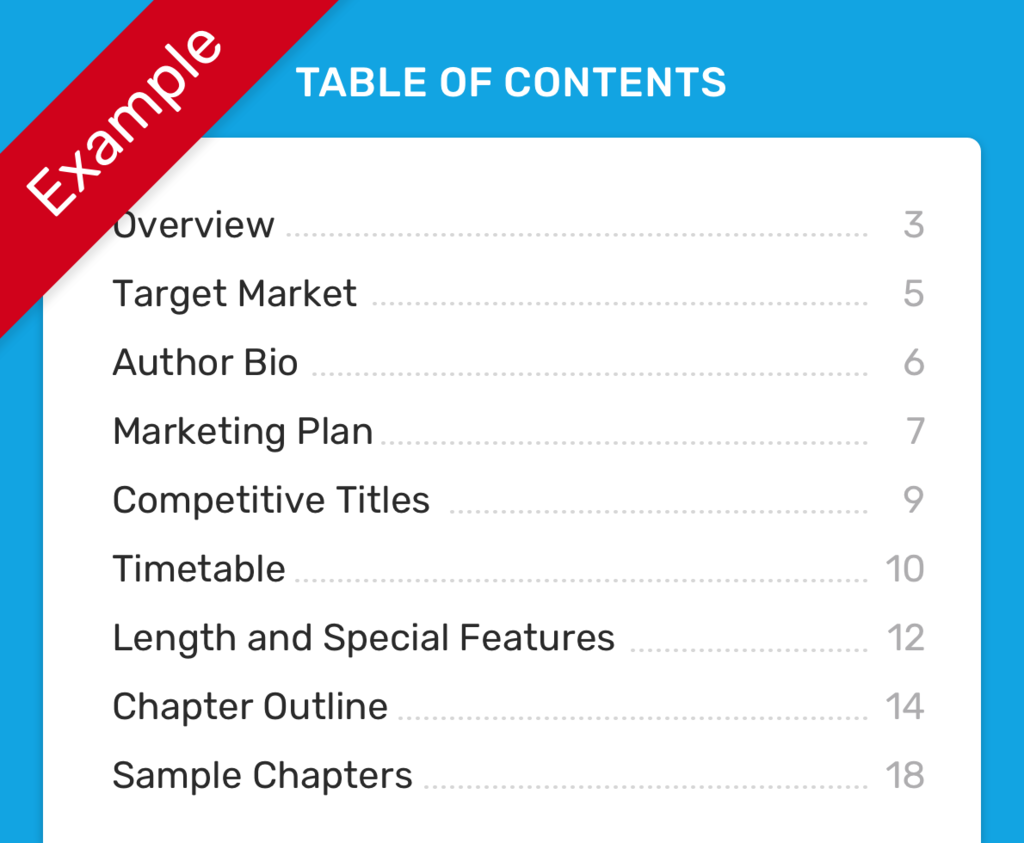

Formatting your book proposal is also important. While publishers may have slightly different specifications for their preferred format, most book proposals are 15–50 pages long and follow a similar structure.

With the help of 10 of Reedsy's top editors and agents, we’ve identified the most common elements across all book proposals:

- Cover page

- Table of contents

- Overview of the book

- Target market

- Author bio and platform

- Marketing plan

- Comparative titles

- Chapter outline

- Sample chapters

- Timeline

- Length and special features

We’ve synthesized all of this into a free book proposal template you can download below.

FREE RESOURCE

Book Proposal Template

Craft a professional pitch for your nonfiction book with our handy template.

However, we don’t recommend filling out the sections in order. Much like writing an introduction to your book, it will be much easier to write a compelling overview once you’ve got the bulk of your argument fleshed out. And what forms the backbone of your argument? The evidence of need. We’ll look at this next.

But first, let’s go on a bit of a tangent and explore an interesting nonfiction edge case: the memoir.

Q: What do agents and publishers look for in memoirs written by non-famous authors?

Suggested answer

When I vet memoir submissions, I'm looking for writers who pay close attention to scene-building. When did this event occur? Who was there? What are some accompanying sensory details? On the flipside, sometimes memoirs don't succeed because information is presented without being tethered to a scene or a narrative. If you're writing about your life as an amateur foosball player, that could be a compelling memoir! But it's a tough pill to swallow when readers encounter 10 pages of foosball history if there isn't an occasion for that material. Better, I think, to spin a yarn, then insert enriching backstory material insofar as the narrative-- and the scene-- requires it.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

"Memoir is difficult." "Memoir is a hard market." "Publishers aren't buying memoir." You don't have to dig far to find these discussions in publishing spaces because, as in every genre, agents and publishers can only take on books that they think they can sell. So a memoir by a non-famous author needs to have a powerful and unusual story to tell and/or to tell a story that is common to many people in an effective way. There's an element of luck, too – the memoir you've worked on for years may just happen to chime with something that's happening in the zeitgeist.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Two words: strong brand. But what is a strong brand? It can mean many things for a non-famous author, including a large platform. Yes publishers and agents will skip through a book proposal to see how many followers the author has on social media. But other factors can tilt the scales in your direction. Do you have famous connections? Would the book be endorsed, or a foreword written by, a famous person. Bottom line, authors must overcome the obstacle of relative obscurity with solid reasons what an agent or publisher should take on the book.

Mike is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Authenticity, personality, and a strong voice that can tell you a story that has something to teach us all

Bev is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Do you need a book proposal for a memoir?

Memoirs are a special case. Some publishers will ask for a book proposal, some will want a complete manuscript, and others will request both. If you already have a strong platform, it may be easier to sell a memoir based on a proposal alone. However, if you’re an unknown author, publishers might not want to invest in your book without seeing a compelling manuscript first. We recommend looking at each agent and publisher’s requirements and reaching out to them for more guidance if needed.

2. Identify a gap in the market

This step is the most important because it forms the foundation of your book proposal by establishing why an agent or editor should take a chance on you. Simply put: it’s your business case.

The market only needs your book (in a publisher’s eyes) if two criteria are met:

- There is a decent-sized audience willing to buy your book, and

- No existing book fully serves this audience’s needs.

You’ll need to present a watertight case for each of these points if you want to land a publishing deal, so it’s vital that you research the market thoroughly.

Find comparative titles

Let’s face it: you’re probably not going to invent a whole new subgenre of nonfiction or chart completely unknown waters with your manuscript. Other people will have already written books in your subject area — so what can you offer that’s new?

To prove to the publisher that your book deserves a place on the shelf, you need to know your predecessors and your competition.

Q: How should authors select comp titles for a book proposal to position their book?

Suggested answer

Comp titles can be hard because most authors don't have the same tools that publishing professionals do when they are evaluating comps (like access to individual titles' sales).

What you should aim for in a proposal is a number of titles, at least 5-7 that are from a variety of different publishers and all have a good sales track without being bestsellers. Again, nothing about this is easy: you as the author should read as many of these books as you can so that you understand the market and where your future book will fit in. It will also help you describe, in the proposal itself, why you've chosen these comps and what makes your books similar but unique in its own right.

Every publisher will want to see at least one comp from their company. You can use things like Amazon reviews or Goodreads to get some sort of baseline as to the popularity of a given book. Amazon's "Customers also bought or read" and "More items to explore" tools can help you find additional titles.

But more than browsing titles and short descriptions, the single best tool you can access is reading widely in the genre you're writing. There simply isn't a better way to know the market than truly knowing the market by reading, reading, and more reading!

Matt is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For a nonfiction book proposal, I advise authors to aim for around five recent books that have sold reasonably well. Of course, if there's a popular or well-known book in the same category as yours, you'll want to include that, but I also encourage authors to think creatively and consider some less-obvious choices. Remember that ultimately, the goal is to establish that there is an eager audience out there for your book. For example, for a recent "small-space entertaining" guide/cookbook, in addition to several general entertaining guides and cookbooks, we also included a small-space decor book as a comp title to highlight the many small-apartment dwellers out there who are looking for resources on how to use their space.

Christine is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Besides your pre-existing knowledge of what has been written and published in your field, you can find your competition by going to an actual bookshelf. Visit your nearest brick-and-mortar bookstore. Figure out where your book would sit, and check out the titles there.

Then go onto Amazon.com and search for books in the category you just identified. Scroll down for the “Frequently Bought Together” and “Customers Who Bought This Book Also Bought” titles. This should give you a treasure trove of comparative books. For your own record, note down:

- Author

- Title

- Publisher

- Publishing date

- # of pages

- Price and format

- Sales figures (if available)

- Who provided blurbs

- Strengths and weaknesses (read reviews to help you work these out)

Now, select 4–8 of the most relevant comparative books from the last 3–5 years. Ideally, these should be familiar (even to an agent or publisher that is not an expert in the subject) but not unreachable.

Editor Geoffrey Stone, for instance, warns you not to pick books by extremely well-established authors, since their platform is likely far bigger than yours. Instead, search their books on Amazon and see what else is suggested in the “Customers who bought this also bought” section.

On the other hand, Sally Collings also warns that you should choose traditionally published titles that aren’t too obscure; these will serve as credible benchmarks in terms of market viability.

Analyze the similarities and differences

The next step is to evaluate your comp titles. How will your book be similar in terms of audience, content, and tone? And more importantly, how will it challenge, update, or enhance the existing literature?

Summarize your analysis in the comparative titles section of your proposal and remember to provide evidence. Aim for a paragraph or so per title; when read as a whole, this section should highlight how your book is both aligned with an existing audience and uniquely positioned in the market.

Q: What are the best strategies for nonfiction authors to select comp titles when creating a book proposal?

Suggested answer

When selecting comparison (comp) titles for your nonfiction book proposal, think of them as the company your book keeps. They help agents and publishers visualize where your book fits in the market and why it deserves a spot on the shelf. Here are some key tips:

Keep It Recent: Focus on books published within the last five years. This shows you’re aware of current trends and helps publishers gauge the book’s potential in today’s market.

Go Traditional: Choose traditionally published titles. They serve as credible benchmarks for what publishers are looking for, especially in terms of quality and market viability.

Successful but Not Untouchable: Look for books that performed well but aren’t necessarily runaway bestsellers. Aiming too high can make your proposal seem unrealistic, while too niche or obscure might suggest there’s limited demand.

Think Like a Bookbuyer: Imagine where your book would sit on a buyer’s shelf. What titles would sit alongside it? This helps publishers see your book’s relevance in its genre or category.

Finally, explain why you chose each title. Highlight similarities in audience, tone, or subject matter while emphasizing what makes your book distinct. A thoughtful comp list demonstrates market awareness and strengthens your proposal.

Sally is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The best advice for comp titles is to include books that have published within the last 3 years and have good sales tracks without necessarily being bestsellers. It's a tough act to balance, especially when you also consider that your comp titles should be from a variety of publishers; you don't want to include four titles that were all published by Penguin Random House and none from any other publisher.

By being well read in the space and knowing what titles are out there, you can craft your comp titles to be a composition of various parts. Your book could take the tone from one title, with the scientific reference from a second title, and combine it with the overall subject matter of a third title, as a rough example.

As for finding comp titles themselves, you need to read, read, and read some more. Reading makes writers, and while you can use websites like Amazon or Goodreads to get a sense of how well a given book has sold or reached its audience, there's no substitute for reading and truly knowing what is contained within a comp title.

Matt is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Dear Writers,

When you are choosing comp titles:

- Read, read, read in your genre.

- Read books that your hoped-for agents have represented. You'll find these listed on their websites.

- Frequent your local bookstores and peruse the shelves. Where is your book going to fit on the bookshelf? What titles are on that shelf? Read the blurbs - do those books have similar elements to yours? Read those books. (You might want to get them from the library ... because if you're a bibliophile like me, it can get expensive!)

- Choose books that were published in the last 2 years. If there's an older-but-perfect comp: 3 years on the outside.

- Read the comps you use, cover to cover. Make notes about how the book is like yours, and how it's not like yours. You'll need this information when you are writing your book proposal, and when you are talking to your agent (when they call you because they loved your query letter). You'll need 4 - 5 comps - two for your query letter, and four to five for your book proposal (for nonfiction). Be sure to include the two you used for your query in your book proposal.

- Check out each potential comp on booksellers' websites. How many people have left reviews? If the reviews are 4's and 5's (out of 5) and the review count is high (in the hundreds at a minimum, in the thousands, even better), that's a good comp. Agents are going to check those numbers, so choose books that have sold well and have lots of positive reviews from readers. But...

- Don't choose a bestseller, even if it's a perfect comp. Keep researching. Look up the book on Amazon and check out the "Customers ... Also Bought" listings under the book's blurb. The books listed there may lead you to other comps that will work for you.

- Check out comps on Amazon and click on the "See All Details" link. What are the book's Amazon ratings? If the ratings are good, choose the book as a comp. If the ratings are not great, record the book's publication information and ratings (you might need them later) and move on.

- On the Amazon ratings list for each book, you'll find a series of keywords categorizing each book. Use those keywords to search for more books in your genre and sub-genre.

Good luck researching your comps!

Michael I

Michael is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Literary agent and editor Jeff Shreve shares a useful reminder: “Don't shy away from describing other books' shortcomings, but be respectful. Odds are that you'll be submitting your proposal to the publishers of many of these competitive titles, after all.”

|

❌ Bad examples of a comp titles section |

✅ Good examples of a comp titles section |

|

Readers of The Shortest History of Germany will like my book. |

Just as readers enjoy The Shortest History of Germany for its breadth, humor, and readability, my book on Belgian history has a similar subject matter, tone, and scope. |

|

My book will appeal to people who found Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals too unrealistic. |

While Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals is largely aimed at people who have significant control over their own schedules, my book will speak to an audience that faces more time constraints in their daily lives, such as single mothers or shift workers. I hope to address some of the shortcomings of Burkeman’s approach by offering practical time management tips, even for those who feel they have no time left over to manage at the end of their day. |

|

The Anxious Generation is sensationalized nonsense. My book will tell people the truth. |

The Anxious Generation has been criticized by academics for relying too heavily on correlation studies rather than establishing causation. My book will re-examine the empirical evidence for Haidt’s claims and discuss new research that seems to contradict his theories. |

Narrow down your target market

You’ll now be in a good position to fill out your target market section. To do this, you’ll need to identify your specific ideal readers. Use your research into comp titles as a starting point but remember to think about other possible groups of readers.

As ghostwriter Barry Fox points out, you are the expert on this market. If you’re a historian, you have a better idea than the publisher of the number of students who are interested in your research area; if you’re a doctor, you know your clients’ worries better than anyone else. Use your expertise to write a couple of paragraphs outlining:

- Who your primary audience is

- Where they can be found

- How your book fulfils your audience’s need

- How many people your audience might be realistically made up of

- Any possible secondary markets

Never say, “My book is for everyone!” Even if you think everyone can benefit from your book, that doesn’t mean everyone will give it a go. To get a better idea of the number of readers who will actually be most likely to pick up your book, look for relevant groups on social media, sales data from similar titles, or surveys on the topic your book will address.

Q: How can authors effectively identify and describe their target audience for a book proposal?

Suggested answer

Authors should read books in the category and genre they are shooting for. There is that old tale about how people in the banks learn to spot counterfeit money--by handling legit money. If you are reading in your target category and genre, you should be able to tell if you book is fitting into that category and genre. That's how you identify your audience, I think. It's time consuming, but I don't think there is a shortcut.

Then to effectively tell an agent who your audience is you might say something like,

XXX is a 30,000-word, MG, mystery novel. Readers who love Taryn Souders' books should like XXX as well.

Just give the word count, the category, the genre, and some comp books. The agent will understand the audience.

Sally is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Start by imagining your target audience as one person—not a vague crowd. Who is this book really for? Give that reader a name, an age, a life stage. Begin with demographics like age, gender, marital status, profession, or family situation. Then dig deeper into psychographics: What do they care about? What values shape their decisions? What do they believe about themselves or the world?

Most importantly, ask:

- What problem do they want to solve that your book helps address?

- What keeps them up at night?

- What do they dream about changing in their life?

Once you’ve gathered this picture, write it out as if you’re introducing that person to an agent or editor. For example: “Meet Sarah, a 42-year-old teacher who…” The more specific and relatable you make this description, the easier it is for publishers (and ultimately readers) to connect with your book.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For nonfiction books it's important that an author understand to whom they are writing. The best way to identify the target audience is to think about your goals for the book. Why are you writing it? Are you interested in sending a particular message to help others in some way? Do you want to share useful information? Do you want people to know more about you and your ideas, maybe because you have a business that offers some kind of service? Why are you sitting down to put these ideas down on paper?

Once you know your 'why', you can identify your 'who': who are the people who will want to read or listen to that message? Are you writing to prospective clients, people interested in a certain topic who just want to know more, colleagues in your industry, people who are struggling with some kind of issue, people with certain goals?

Once you know 'who' - you can do some research to look at the demographics of your target reader. If you're writing about a certain approach to a problem: who has the problem? What is their typical gender, age, location, and economic level? Why are they motivated to buy a book on the topic? What other books have they read related to this topic?

When you're writing about your audience in a book proposal, use those demographics. Tell the publisher who will be most likely to want to read your book - give numbers, such as "X% of women in this age group are interested in losing weight" or "Y% of respondents to a survey said they were concerned about raising healthy kids". Find credible sources (and cite those sources in the proposal). You can also let the publisher know what other, similar books your target reader has likely read, especially if that book has positive feedback and has sold decently well; for example: "The reader has enjoyed books like "Guns, Germs, and Steel".

Identifying a motivated target reader is absolutely vital to being successful in submitting your work to publishers. Publishers need to know there is an existing audience that will want to buy your book.

Melissa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Then, you can write your target market section. Here are some examples of what you might want to say (and not):

|

❌ Bad examples of a target market section |

✅ Good examples of a target market section |

|

My target market is people interested in history. |

My target market is adults with little to no background in the history of Europe who are interested in obtaining an easily digestible overview. |

|

Everyone wants their child to do well at school, so my target market is all parents. |

My target market is parents of 14–16-year-olds living in the UK who want to gain practical insight into how to actively support their child’s education. A 2025 study found that 7 in 10 British parents had taken time off work to help their child revise for their GCSEs, proving that many parents are actively seeking better ways to assist their teenagers with their school work. |

|

My target market is 4–6-year-olds who want to learn to read and learn about the world at the same time. |

My target market is parents and other adults buying learn-to-read books for children aged 4–6. In my 20 years as a kindergarten teacher, parents have consistently asked me for informative yet accessible nonfiction books for their children; I believe my book fits this description exactly. |

3. Show that you’re the best person to address that gap

So far, you’ve proven that there’s a need for your book; now it’s time to convince the publisher that you can fulfil that need. This will be the focus of your author bio section.

Your bio should do two things:

- Explain what makes you the authority on your subject, and

- Communicate the size of your reach.

To demonstrate your authority on your topic, you can include:

- Formal and informal qualifications

- Awards and recognition

- Previous publications (including articles as well as full-length books)

- Teaching positions or other adjacent work experience

- Speaking engagements

But being knowledgeable about your subject isn’t always enough. In many cases, there are plenty of other people with the same expertise as you. To really convince the publisher that your book will be a success, you should also try to show them that your name can sell.

If possible, include details on:

- Your social media following

- Media appearances and contacts

- Connections to VIPs in the industry

If you've made a name for yourself educating people about fire hazards on TikTok or you have personally interviewed fire marshals in New York City, this is the place to name-drop.

Literary agent Mike Loomis believes that your author platform is the single most important thing a publisher will look for in a proposal. “Publishers know they can work with the author, bring in an editor/ghostwriter, and polish almost any manuscript. But they can rarely create a buying audience out of thin air.”

Q: What types of nonfiction authors are likely to succeed without an agent, and why?

Suggested answer

If you are a celebrity or significant political figure and are really going to only write one book, you are probably better off having a lawyer who bills by the hour than an agent to whom you have to pay 10-15%. Examples of people who used a lawyer instead of an agent include President Bill Clinton, Nikki Haley, Karl Rove, Janet Yellin among others.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you have a large platform (like a big social media following, an influential organization, or an active speaking career), take a look at the world of hybrid publishing. Hybrid publishing allows you to bypass the agents and editors in the traditional publishing world, and gives you more control over your finished product.

Hybrid publishing can be expensive. It's worth the investment if the book is a tool in your tool belt, and a way to build more authority in a field in which you're already well-known. If you are confident that your platform can drive sales without a dedicated publisher marketing team, it can be a great option!

Kate is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In other words: if you don’t already have a strong author platform, you should start building one right away. If you need to submit your proposal sooner than you can cultivate a decent fan base, make sure you state what you’re currently doing to grow your audience.

Keep the author bio short and sweet — and exclude all irrelevant information (your eye color, your level on Candy Crush, etc.). Be honest, purposeful, and specific, highlighting your assets above all.

|

❌ Bad examples of an author bio |

✅ Good examples of an author bio |

|

I have a degree in psychology and have made significant contributions to my field. |

I hold a PhD in Behavioral Psychology from Stanford and my research on habit formation has been cited in over 200 academic papers. |

|

I have a lot of followers on social media. |

I have almost 700,000 followers on TikTok, posting daily educational content on fire hazards that typically receives 400,000+ impressions within the first three days. |

|

I am working on growing my author platform. |

I am actively building my author platform through my email newsletter (currently at 800 subscribers with 25% growth in the last month), weekly appearances on industry podcasts (such as “Startup Stories — Mixergy” and “Bang the Drum”), and my corporate speaking program. I am on track to reach 10,000 newsletter subscribers and 30 speaking engagements by the time of publication. |

4. Create a realistic marketing plan

On a related note, some publishers may ask you for a marketing plan. If so, know they’re not saying, “Tell me what to do in order to sell your book.” Instead, they want to see that you are currently able to reach your target market via your author platform.

After writing your author bio, you should already have a sense of how to leverage your pre-existing audience for a successful launch.

Consider these questions:

- Are there VIPs in your field whom you can ask for a blurb?

- Can you reach out to the organizers of speaking engagements you’ve done before?

- Can you secure an article or interview through your media contacts?

- Do you have a strong subscriber base to your newsletter?

- Do you have connections with bookstores, libraries, or universities who can distribute your book?

If you don’t know any higher-ups or have a list of university deans on your Rolodex, don’t throw in the towel just yet; there are other ways to prove your marketability.

Q: Why do nonfiction book proposals require an author platform and marketing plan?

Suggested answer

You don't need to know about marketing, but you do need to convince them there is a market for your book. Let them know how big you believe the potential market is, why you believe it's so, and how you can deliver that audience.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Publishers, at root, are marketing companies. They operate in a highly competitive market with tight margins. They don’t like to take risks. If an author, or potential author can demonstrate good marketing chops, and strong social media skills, or – better still – an army of followers, they are far more likely to be taken on. Any published writer will tell you that being a successful author these days involves as much selling as writing.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You can find more marketing ideas in Barry Fox’s Reedsy Live webinar on book proposals, but the general gist is to make use of all the assets you’ve listed in your author bio (and say how you’re planning to acquire even more). Again, the key is to be specific.

|

❌ Bad examples of a marketing plan |

✅ Good examples of a marketing plan |

|

I will talk on podcasts. |

I’ll arrange a guest appearance on my former colleague’s podcast “AI and Academia,” which has 40,000 weekly listeners. |

|

I will get a blurb from a famous psychologist. |

I have three professional contacts I can ask for a blurb: Dr. David Hunt, a renowned psychologist with whom I conducted research back in 2022; Dr. Keerthana Ravindran, a lifestyle coach with 800,000 Instagram followers I connected with at a conference; and Dr. Lenka Grabowski, a prominent member of the International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP), which I too belong to. |

|

I will try and contact Elon Musk for an endorsement. |

I am signed up to attend 5 conferences in the next 4 months to expand my professional network and make more connections in the industry. |

5. Outline the structure of your book

Now that all market-related issues are covered, you’re finally ready to elaborate on the actual content of your book! By this point in the proposal, the publisher will hopefully be on board with your idea — they just need to know that your plans for writing the book are viable too.

Show that a full manuscript is right down the road by providing a chapter-by-chapter sketch of your book (just one or two short paragraphs per chapter will do). If you don’t have a clear idea of where to begin yet, perhaps this guide on how to outline a nonfiction book will be useful.

Remember that the chapter outline will show your approach to your idea. To that end, make sure that the progression of your chapters is clear and purposeful. Editors acquire books across a broad list, so you should also steer clear of industry-specific jargon that may only fetch you glazed eyes in return!

|

❌ Bad examples of a chapter outline |

✅ Good examples of a chapter outline |

|

This chapter will examine MSCI’s adjusted EBITDA, EPS, and beta of 1.5 in the context of its 2016 non-GAAP measures. |

This chapter will examine MSCI's 2016 financial performance and how the company chose to present its results to investors. |

|

Chapter 7 will expand on Chapter 6 in greater detail. |

Chapter 7 will take the basic budgeting framework from Chapter 6 and show readers how to apply it to more scenarios: managing irregular income, planning for major expenses like buying a house, and adjusting budgets during economic uncertainty. |

|

This chapter will be dedicated to comprehensive coverage of 15 different meditation techniques (Vipassana, Zen, Transcendental Meditation, Loving-kindness, Body Scan, Walking Meditation, etc.), with precise timing protocols (ranging from 3-minute micro-sessions to 45-minute intensive practices), specific breathing patterns (4-7-8 technique, box breathing, alternate nostril breathing), and detailed instructions for 31 different seated postures. |

This chapter will present 15 meditation techniques for readers to try at home, giving detailed instructions on timing, breathing patterns, and positions. The techniques will be divided into clear subheadings and accompanied by helpful graphics. |

6. Summarize your proposal in an overview

Congratulations — you’ve done the bulk of the hard work. Now you can go back and write a strong overview.

This will be the first thing agents or publishers read, so Sally Collings emphasizes that it must “grab attention, convey your book’s essence, and excite them to keep reading.”

Q: What section of a book proposal do agents and publishers prioritize most, and why?

Suggested answer

At the end of the day, selling books is a business, i.e., it needs to make money. Of course, books also need to be well-written, meticulously researched, and creatively compelling, but no matter how brilliant a book might be, if nobody buys it, publisher won't consider it to be a success. All of this why the marketing section of the proposal is often the most important part of the proposal--it's where authors lay out why they think readers will care about their book and buy it. What problem does the book solve? Who are the readers and how will they find the book? What aspects of an author's background, training, connections, audience involvement, etc. will allow them to reach their readers?

Marketing is key. Being able to connect with prospective readers and their communities is key. Fortunately, many books have been written about marketing strategies and about how to write successful proposals, so even if an author has zero marketing experience, it's very possible (and even fun!) to explore marketing and PR tactics.

Lisa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What agents and publishers want is to get a feel for this book, your ability to write it, and its ability to sell a lot of copies. All parts of a proposal are important, but the agents and publishers are very interested in concrete evidence that you are going to sell a lot of copies. So, should you have a social media following in the millions, your own podcast, thousands and thousands of employees who will be required to buy a copy, you should mention that in your proposal.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Agent and publishers are busy people. They often don't get beyond the first sentence of a submission so it's important to make the opening of your sample chapters as intriguing as possible. The same goes for the query letter - it should be brief, succinct, professional and clearly outline what you've written, why you've written it, how many words it is and whether you've been published elsewhere.

Vanessa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

An overview will usually be one to two pages long and should hit the key facts about your book: its topic, themes, and intended audience. The overview will also provide insight into the significance and reach of the book, explaining why the subject matter is important and how this book is unique or will fill a gap in the market, as well as why you’re the perfect person to write it — everything you’ve already figured out above.

This is also a chance to give the agent or publisher a taste of your narrative voice, so make sure it aligns with the intended tone of your book.

Perhaps most importantly, an overview includes the all-important “book hook” that engages readers.

Start with a short elevator pitch

As Elmer Wheeler put it once in The New Yorker: “The sizzle’s sold more steaks than the cow ever sold, although the cow is, of course, mighty important.”

Your proposal needs that “sizzle” at the start of the overview to keep agents and publishers reading. It can be a story, anecdote, thought-provoking question, or compelling statistic — but it must make the subject of your book sound intriguing, new, or pressing. Think of the way the first paragraph in a magazine article grabs the reader’s attention, and try to emulate that effect.

For a better idea of what we mean, take a look at this example from an actual book proposal sample for a memoir Reedsy ghostwriter Andrew Crofts co-wrote with author Hyppolite Ntigurirwa:

This is the shocking and inspirational memoir of a boy who survived the Rwandan genocide. When he was seven years old, Hyppolite lost eighty members of his extended family and witnessed the murder of his beloved father.

Born in a mud hut without shoes, water, or power, he struggled after the genocide to gain an education and to learn to forgive the killers.

The personal story hooks the reader because it is both shocking and intriguing. How could Hyppolite possibly learn to forgive the killers after all that had happened to him?

Answer the three W’s

After your one- to two-sentence elevator pitch, the rest of your overview should answer these three W’s:

- What is your book about?

- Why does it need to be published now?

- Why are you the right person to write it?

Keep your overview concise and avoid technical jargon (or, if absolutely necessary, provide definitions). Stick to one to two pages max. Remember: your writing skills are being judged at all times — not just in your sample chapters!

Here are a few snippets of a hypothetical overview for a book on leadership skills to help illustrate how to approach it:

|

❌ Bad examples from an overview |

✅ Good examples from an overview |

|

Leadership is important in today's business world. This book introduces a revolutionary new leadership strategy. |

The average CEO tenure has dropped from 10.8 years in 2015 to 6.8 years in 2025 — not because CEOs lack technical capabilities, but because they never learned the one leadership skill most MBA programs don't teach. |

|

CEOs need leadership advice now more than ever. |

With remote work making traditional command-and-control leadership obsolete, CEOs urgently need a new management playbook for the post-pandemic workplace. |

|

I’ve worked with CEOs as an executive coach, so I know what works and what doesn’t in a leader. |

As an executive coach who has worked with 47 Fortune 500 CEOs over the past decade, I've identified the single most important practice that separates transformational leaders from those who simply manage decline. |

Get your book proposal reviewed by pros

John B.

Available to hire

I specialize in children's books because kids will be your best critics and biggest fans -- next to a good editor.

Frances G.

Available to hire

Children's editorial director at a "big five" publisher, with 31 years of picture book experience. Author of ten published children's books.

Sirah J.

Available to hire

Careful inspections, thorough explanations, and considerate guidance for inclusive picture books and middle grade novels.

7. Select your best sample chapter(s)

Now, with most sections of your book proposal written, it’s time to give the agent or publisher a bigger taste of what you can do. You don’t need to produce a full manuscript yet, but publishers will expect a sample chapter or two, demonstrating that you have the skills needed to put your ideas into writing.

We’ve saved this step until now at the advice of Jeff Shreves. “Once you have the full chapter outline and the overview nailed down, it will become much clearer which chapter you should highlight.”

Q: How do you maintain an author's voice while editing nonfiction?

Suggested answer

I never put my own stamp on an author's work! I generally highlight areas where I'd like an author to expand so that they are providing the new writing themselves.

Rennie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you're an editor with enough experience, this comes naturally. The most important thing is to realize that the work needs to reflect the individual and his/her/their connection to the subject matter. You edit only to clarify, correct, etc.--not to express your own personal opinions about the subject matter, or to make their voice like your own. Editors in any case are there in service to the work and to writers to accomplish what they want for that work. Honesty is always important--but a writer's voice is as unique as a fingerprint. Changing that is not our job.

K.j. is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Since I have already given the author a sample edit, they’ve been able to assess whether I understand their intention and “hear” their voice clearly. Some authors have honed their voice over years and multiple projects while others are still working theirs out. I get a sense of this to begin with, and clarify with them what they are hoping to achieve with the editing I provide. Sometimes I will read an author’s other work or we may have a video call to discuss what they need. Once I have the full manuscript I read it thoroughly, “listening” to it, getting familiar with it. My task is not only to honor their unique voice, but to help bring it forward clearly, somewhat like a microphone or sound system is designed to bring a singer’s voice forward so the audience can hear it clearly. My goal is to understand the author’s intention and partner with them to achieve that goal. I can reflect back to them whether they are being consistent, or how a particular style may come across—is it having the effect they want or is a certain technique only distracting? I make notes or ask questions in the margins and the author can respond there so our conversation stays connected to the area of the book we are discussing. I find this collaborative approach to be the most effective way to maintain and empower the author’s voice and intention.

Clelia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Pick a chapter that best captures the essence of your book. Which chapter exemplifies the selling point you promoted in your overview? For a memoir, it might be your first chapter which sets the scene for your story. Or if you’re writing a business book, you might find that a later chapter about how your business took off after some experimentation in strategy could better show your potential. Try to find heavy-hitting chapters that stand well alone.

You also want to make sure each sample chapter begins with a strong hook. Author and editor Vanessa Curtis warns that publishers are very busy people and will only keep reading if they are intrigued from the start.

The table below shows some types of chapter hooks that are often successful in nonfiction, along with real examples of their usage in successful nonfiction titles.

|

Type of hook in nonfiction |

Example |

|

Interesting personal anecdote |

I didn’t realize I was black until third grade. ~ Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld |

|

Surprising fact or statistic |

There was a moment in 1940, the bleakest year of the Second World War with the Wehrmacht carrying all before it, when Winston Churchill made the French government a curious offer. He suggested a merger of the British and French states. ~ Unruly: The Ridiculous History of England's Kings and Queens by David Mitchell |

|

Insightful quote |

“Statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write” ~ How to Win the Premier League: The Inside Story of Football’s Data Revolution by Ian Graham |

|

Thought-provoking question |

Is there any knowledge in the world which is so certain that no reasonable man could doubt it? ~ The Problems of Philosophy by Bertrand Russell |

|

Bold claim |

There is no such thing as the future. The future is an illusion. ~ Managing Thought: Think Differently. Think Powerful. Achieve New Levels of Success by Mary J. Lore |

|

Amusing joke |

If you took the whole of Norway, scrunched it up a bit, shook out all the moose and reindeer, hurled it ten thousand miles around the world, and filled it with birds, then you’d be wasting your time, because it looks very much as if someone has already done it. ~ Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine |

In addition to being engaging, sample chapters should follow the rules for proper manuscript formatting.

Q: Do you have any words of encouragement for authors struggling in the querying trenches?

Suggested answer

First of all: don’t give up. Rejection isn’t the end of the story—it’s part of it. Every “no” is simply a redirection toward the right “yes.”

Publishing is absolutely a business, but it’s also deeply relational. Editors and agents love working with people they genuinely like and trust. That means: go to writers’ conferences. Join a critique group or hire an author coach. Get to know professionals in the industry, not just for what they can do for you, but for how you can show up as generous, authentic, and collaborative. You never know when a writer friend might one day endorse your book, or when a connection you make over coffee might become a career breakthrough.

And here’s the bigger truth: querying is more than chasing contracts. It’s also a personal growth journey. You’ll discover your resilience, refine your craft, and grow into the writer you’re meant to be. One author I know literally turned her pile of rejection letters into a lampshade and said they helped light her way to publishing three novels.

Need more inspiration? Catherine Stockett, author of The Help, was rejected by 50 agents before one finally said yes. That “yes” led to a book deal, a bestseller, and eventually, a movie.

So hold fast to your dream. If you feel called to write, you probably are. Keep writing. Keep connecting. Keep becoming the kind of author people want to root for. The path may be long, but you’ll be stronger, wiser, and more yourself because of it.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Querying can be emotionally challenging and overwhelming for authors. Once you're in it, you're amongst a sea of probably tens of thousands of other authors at the same time, and there are, of course, only so many agents and agencies out there. Truthfully, the odds are not great; an agent will sign only about 1-3% of the authors they come across in their queries. This is why the query must be in tip-top shape: a query's only job is to make the agent curious enough to ask for pages. Then, they have to fall in love with the pages (the writing and the story, which are two different things) and have a vision for it in the current market.

If you go into it with the right mindset, it can make it easier. Expect to receive many passes; it's inevitable in 99.9% of cases. Your story isn't for everyone; no one's is. And there are so many reasons an agent might pass. Try not to take it personally; if they pass, then they were not the agent for you. You have to have thick skin though. Not every agent will reply, and if they do, they may give feedback or a reason they're passing or they may not. It's hard not knowing, but there's not much you can do about it. Agents are not paid for the time they spend on queries, and their top priority is the clients they already have, so unfortunately, queries often fall to the bottom of the priority list. And because we receive so.many.queries, it's very difficult to stay on top of them all. We simply don't have the time to respond to everyone. All you can do is do your best; ensure your query is spectacular so that it stands out, your pages are spectacular so agents see it as ready or nearly ready for submission to publishers, and research the agents and agencies first so you know you're shooting your shot with the most appropriate people in the industry. Follow their submission guidelines, don't cheat, and be friendly and professional. Get several pairs of fresh eyes on your query so you know it contains all the necessary elements (and doesn't contain anything that shouldn't be in it) as well as your manuscript, and make sure everything is ready before you begin querying. Being prepared says a lot about your work ethic, which is important to agents as well

It sounds cliche, but the only difference between those who find representation and those who don't is that the authors who found representation didn't give up. It takes patience, persistence, and perseverance. And it may not happen with your first completed manuscript, or even your second or third--but if your goal is to find an agent and be traditionally published, keep going. Keep learning, keep trying, keep connecting with other writers and industry pros. You've got this!

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Don't be afraid to tear up your query letters and start again. Be aware of the time of year -- you may be going 24/7/365 but agents and publishing houses don't do that. Check out Writer's Digest articles on query letter writing and examples of winners and losers. Check out Query Shark. Understand the different agent types and editors at small presses -- different query styles may be required. Send queries out, mark the calendar 4 weeks from that date, and forget about them until then.

Query letters are not a sales letter about you -- you love your book, your letter needs to make anyone want to love your book as well. :O))

Check out writing blogs/websites such as those of folks like Anne R Allen or Janice Hardy -- or any author you admire -- their tips on query letters may include something you've never considered.

Start your next book... c'mon! You might be surprised what's waiting to pop outa your head!

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you don’t want to worry about formatting a chapter yourself, you can write it in Reedsy Studio and export it for free. We’ll do all the formatting for you automatically.

8. Present the logistics of your book

At this point, you can briefly cover the practical logistics of writing your book. Let the publisher know:

-

What timeline you suggest for drafting the book;

-

What range the word count might fall in (including references and appendices); and

-

What tables, graphs, or images you’ll need to include.

Of course, these are open to discussion once you get an offer, but publishers will appreciate the heads-up!

9. Don’t forget a cover page and table of contents

Finally, update your table of contents with the correct page numbers and add a cover page. The cover page only needs to include the book’s title, its subtitle (if applicable), and your name — or names, if you are co-authors.

Once you’ve double-checked for typos (a must for any piece of writing), there’s nothing left to do but submit your proposal to agents or publishers. For help keeping track of your submissions, download our free query tracker spreadsheet.

FREE RESOURCE

Query Submissions Tracker

Stay organized on your journey to find the right agent or publisher.

Good luck!

5 responses

liladiller says:

08/03/2018 – 03:42

Under #5, where is stage 2?

↪️ Reedsy replied:

14/03/2018 – 20:24

Hi Lila — Stage 2 is the analysis portion of the Competitive Titles section :) It's all evaluation of your 4-8 comps from that point on.

Patty says:

04/06/2018 – 11:17

The above post seems to be for commercial non-fiction. What about a memoir? Wouldn't that be different? How?

↪️ Reedsy replied:

07/06/2018 – 04:45

You're correct, Patty — memoirs fall into a bit of a gray area when it comes to book proposals. Could you drop us an email at service@reedsy.com with a brief description of your memoir? I'll be able to point you in the right direction from there :) – Yvonne from Reedsy

Anne says:

24/09/2019 – 20:12

What about a series? My book is an overview with human interest stories, how to do projects that lasting records of the several heroines.