Guides • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Parts of a Book: Front Matter, Back Matter and More

Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

View profile →Most printed and published books can be divided into three sections: the front matter (like the cover, copyright page, and table of contents), the main body of the book, and the back matter (like acknowledgements and indexes). Together, they help organize information for the reader.

In the table below, you can see a more detailed breakdown of what goes into each part of a book:

|

📘 Front Matter |

📖 Body |

📚 Back Matter |

|

Accolades – Praise and reviews |

Prologue – Sets the stage (fiction) |

Acknowledgements – Thanks and credits |

|

Copyright Page – Legal and publishing info |

Introduction – Context for the topic (nonfiction) |

About the Author – Author bio |

|

Title Page – Title, author, publisher |

Chapters – Main content |

Appendix / Addendum – Extra info (e.g. research) |

|

Dedication Page – Says who the book is “for”, often with a note of thanks |

Epilogue – Concludes the story, often with a “bonus” scene (fiction) |

Endnotes – Supplemental notes (e.g. citations) |

|

Table of Contents – List of chapters |

Conclusion – Wraps up ideas (nonfiction) |

Index – Key terms and pages |

|

Epigraph – Quotation which suggests the book’s theme |

Afterword – Author’s reflection |

Bibliography / References – Source list |

|

Preface – Author’s own introduction |

Postscript – Final note or update |

Bonus Material – Extras or previews |

☝️ Note that no book will include all of these parts at once, and you may occasionally find things like the copyright page in the back matter rather than the front matter too.

In this guide, we’ll dissect the different parts of a book, covering which components can (and should) be included in the final product. In subsequent sections, we'll burrow deeper into the most common and important sections of a book's front, body, and back matter. But first, let's start with a wide-angle view, beginning with...

The front matter of a book

The front matter of a book is everything between the front cover and the very first pages of the main text: the title page, copyright page, table of contents, etc. These pages are usually not written by the author themselves, but rather by someone familiar with their work or the publisher, and the pages are usually not numbered.

Q: What are the most effective ways for authors to begin monetizing their writing, particularly in the early stages of their career?

Suggested answer

At the beginning of your writing career, the best way to turn a profit is to be thoughtful and innovative when looking at your work.

Many new writers begin with self-publishing novellas or ebooks, which are inexpensive to produce and can be distributed to readers in rapid order.

Platforms like Smashwords or Kindle Direct Publishing permit the earning of royalties as well as developing a reader base.

Short stories appearing in literary magazines, anthologies, or contest publications also generate income and exposure.

Besides publishing, the majority of authors offer ancillary services—blogging, freelance, or ghostwriting—to generate a reliable flow of income and hone their writing skills.

Achievement in the beginning more likely comes from stability, reader engagement, and smart marketing: building a mailing list, establishing an internet presence, and cooperating with specialty communities relevant to your genre.

Money-making is never instant, but every action generates momentum toward a lucrative writing career.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Take advantage of every single opportunity that comes your way in the beginning. Don't be too picky. If the front door is locked, go in the side door. Or find a window. I had great luck with blind queries in the beginning and that was before email, kids. I built many relationships that way, and most of all, keep believing in your talent, be agile, be diligent, and above all LEARN HOW TO SELL YOURSELF.

Bev is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you are a non-fiction author you can use your book as a platform to get speaking engagements even before your book is published. Once it is published, ask the business you are speaking for to purchase books for each of the conference attendees and then include this purchase in your speaking "package."

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If by "best," we mean "fastest," then self-publishing is the way to go, since there're no gatekeepers, meaning no wait time. As soon as your book's done, you can get it up for sale. But if we mean best as in "long-term for your career," that becomes a fuzzier proposition because you need to weight the wait time, rejection, potential rewrites/edits, and possibility of never having something accepted inherent in traditional publishing against the prestige that still comes with making it into that world. It also depends what level of control you want for your work. You obviously get much more with self-publishing, but perhaps you'd benefit from the edit you might get from an editor at a legacy press. Lots of variables here, but my advice is always to be honest with yourself regarding your goals.

Legacy prestige is great and all—and, if it goes well, can be much more lucrative—but there's a lot to be said for having full control of your product.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Though many readers skip right over it, the front matter contains some pretty important information about the book's author and publisher, not to mention fine print legal text. And for those who do read it, the front matter can form their first impression, so it’s important to get it right!

🤓 Literary theorist and scholar Gérard Genette suggested that all the additional pieces of information that sandwich a story, such as author name, preface, and illustrations, actually have an effect on how we interpret the main text. He referred to this as “paratext.”

📱Ebooks can sometimes be formatted slightly differently, but generally follow the same patterns as print books with a title page, copyright page, preface, and so on. However, many ebooks will have a clickable table of contents that helps you navigate to the right chapter, even if the print book does not contain a table of contents.

Now, let’s take a closer look at what you may find in the front matter, in the order you will usually find it:

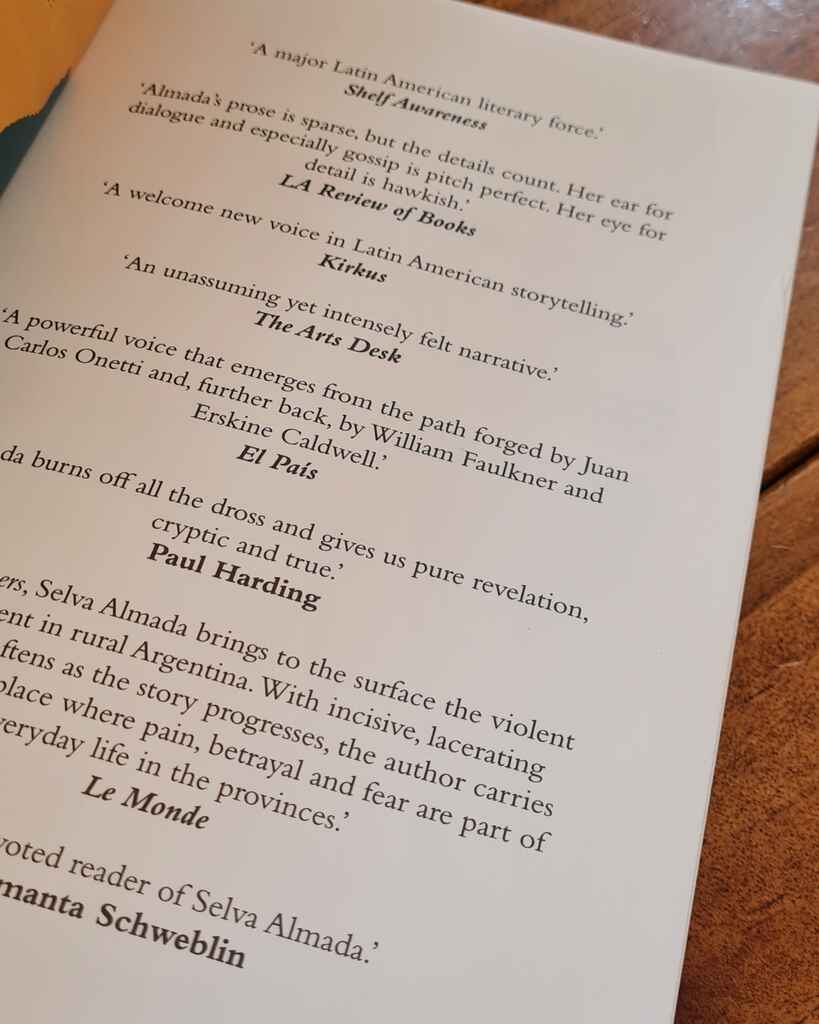

Accolades

Many publishers will put any praise and rave reviews from reputable sources on the cover, and those that didn’t fit on a separate page in the front matter of the book. The placement means that it’s one of the first things readers will see if they flip through the pages in a bookstore, which could help further persuade anyone who is still on the fence.

Praise for Selva Almada 's Brickmakers.

Check out Ricardo Fayet’s free guide "How to Market a Book" to learn about the power of a good review.

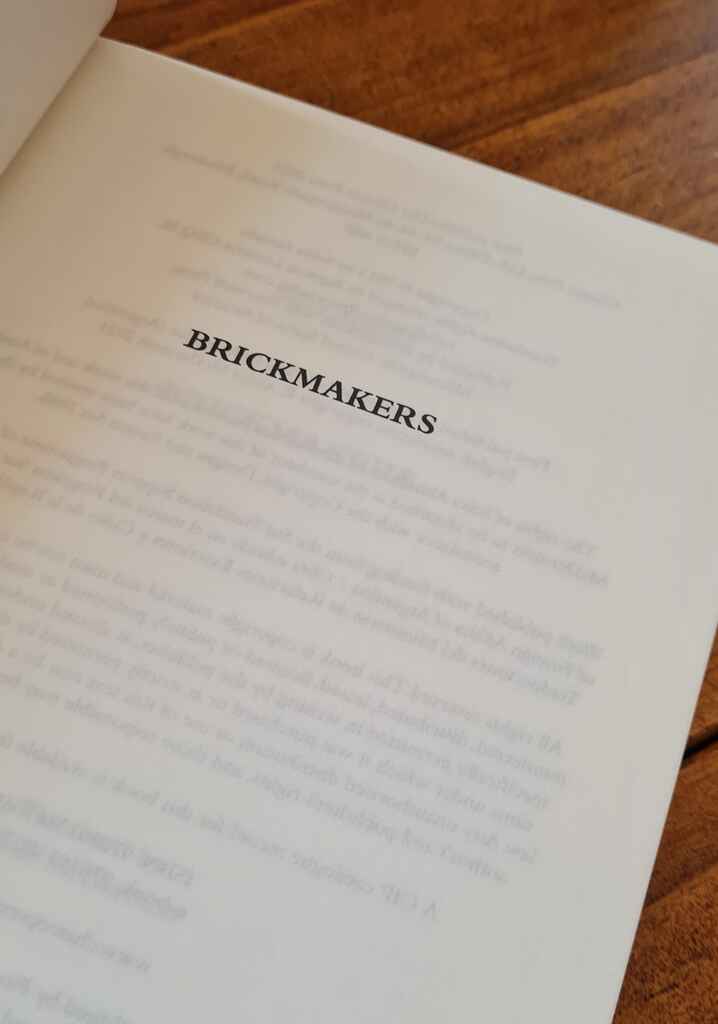

Half-title

Also known as the bastard title page, the half-title page is a blank page with nothing but the title of the book, written in a plain font without frills or decorations.

Half-title or bastard title page of Selva Almada’s Brickmakers.

Traditionally, when readers bought books without covers and added their own, custom-made leather covers, the purpose of the half-title was to protect the more ornamental title page and frontispiece (more on this later) during the bookbinding process. Now, it’s the perfect place to ask for an author signature.

Copyright page

Also called a “colophon,” the copyright page includes technical information about copyrights, edition dates, typefaces, ISBN, as well as your publisher and printer info. It usually appears on the reverse of the title page, if not already taken by the frontispiece, and occasionally in the back matter of the book.

☝️ If you’re not sure what information needs to go on your copyright page or how to set it up, you can simply input the information into Reedsy Studio — our free online writing tool — and it will automatically generate your copyright page for you, along with any other parts you want to go in the front matter, body, or back matter of your book.

Meet the top book interior designers on Reedsy

Andy M.

Available to hire

Experienced, versatile book designer for fiction & non-fiction covers and interiors. Clients include Macmillan, OUP, Pearson & Scholastic.

Megan K.

Available to hire

A designer with a passion for books and a comprehensive knowledge of both traditional and independent publishing.

Steve M.

Available to hire

I've enjoyed creating MG, educational and fiction books for 30+ years. Let's make a book for children, adults, parents & teachers will love!

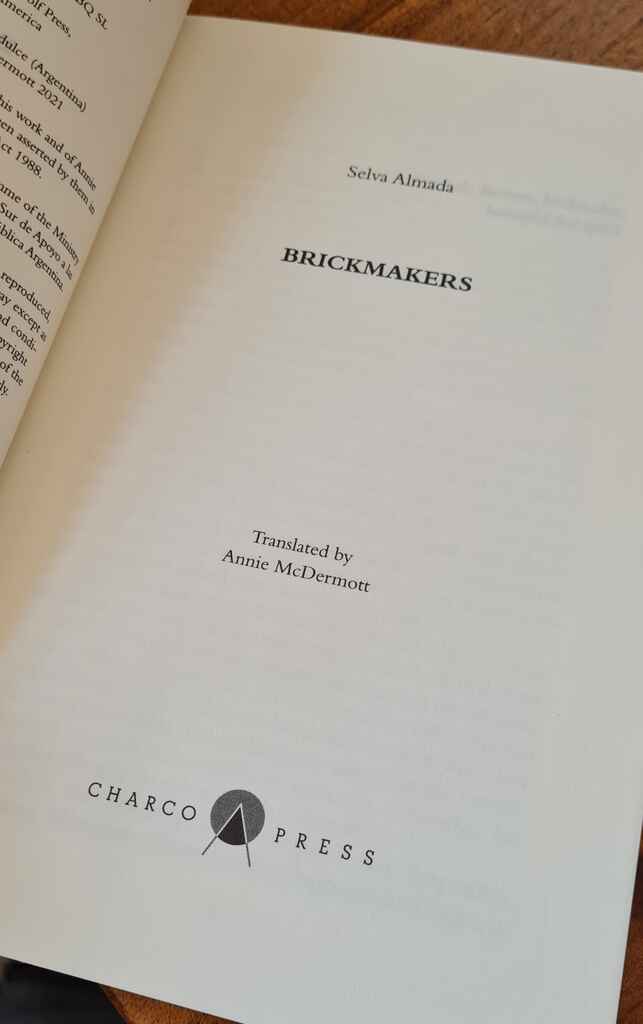

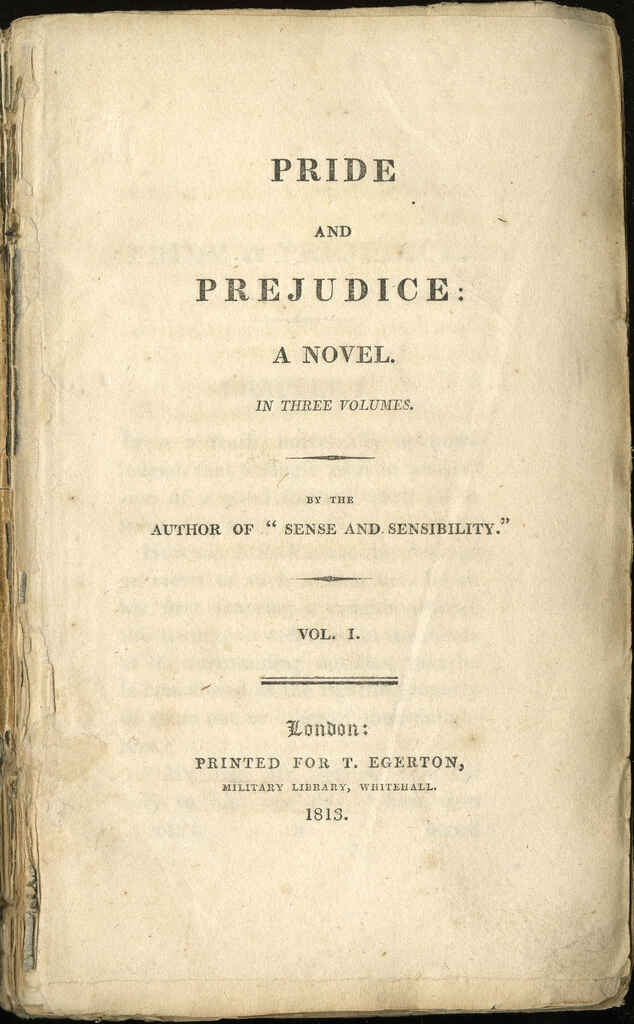

Title page

The title page features the full title of the book and the author's name — as they appear on the cover — and any potential subtitle, translator, as well as the logo or name of the publisher. It can be plain or ornamental, depending on the publisher and author, and will always go on the right hand side of a spread (also known as recto).

Title page of Selva Almada’s Brickmakers.

Title page of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice.

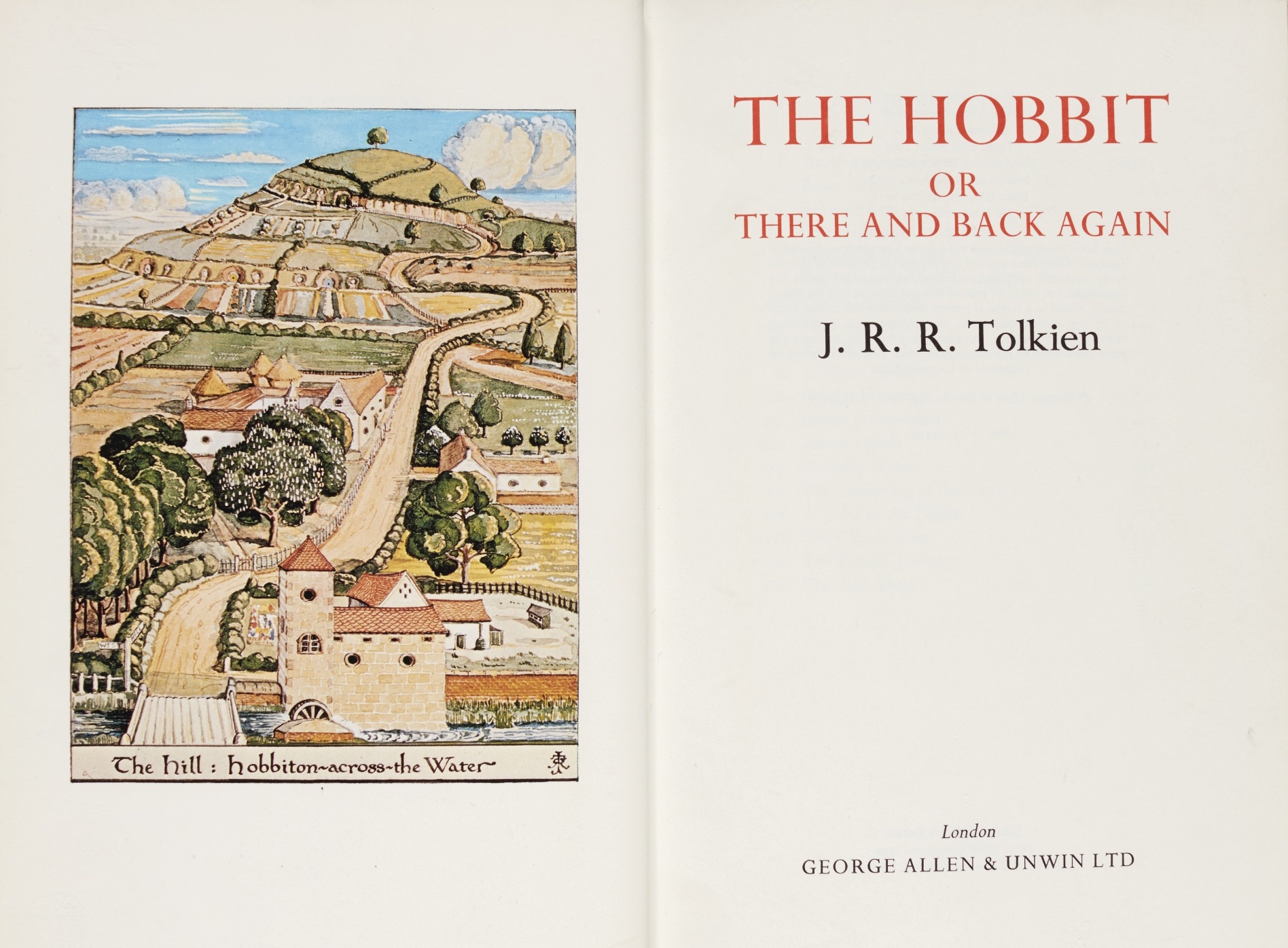

Frontispiece

The frontispiece is a decorative illustration or photo on the page on the left hand side (also known as the verso) of the title page. It is not as common in contemporary books as in older books, but then again, most contemporary books have decorative covers instead.

Also by the author

If the author has published one or more books before the current title, the front matter might include a page outlining their oeuvre, whether standalones or part of a series. This page usually goes on the left hand side, and may replace the frontispiece, for example.

Dedication page

The dedication page is, like the name suggests, a page where the author names the person or people to whom they dedicate their book, and why. This typically comes after the copyright and title page on the right hand page, on a spread of its own.

Austenland author Shannon Hale’s dedication to everyone’s favorite Mr. Darcy.

Table of contents

Some books, mainly anthologies, poetry books, nonfiction, and ebooks will also contain a table of contents to make navigation easier. This is a list of chapter headings and the page numbers where they begin. The table of contents (abbreviated ToC) should list all major sections that follow it, both body and back matter.

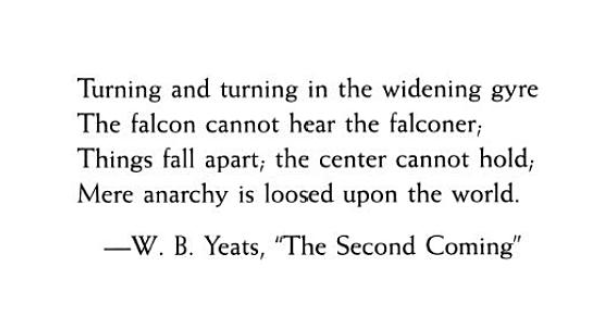

Epigraph

A quote or excerpt that indicates the book's subject matter, the epigraph can be taken from another book, a poem, a song, or almost any source. It usually comes immediately before the first chapter and is intended to hint at the theme or contents of the book.

Preface

An introductory passage written by the author, a preface relates how and why the book came into being, or provides context for the current edition.

Foreword

An introduction written by another person, usually a friend, family member, or scholar of the author's work to introduce the wider context of the piece or to set the reader up for what they’re about to read.

The body of a book

What most people think of when they think of a book — the main text — is referred to as the “body” of the book and goes between the front matter and back matter. For readers and writers alike, this is where the magic happens — it's not just the content that's crucial, but also how you arrange it, which is what we'll cover next.

Prologue (for fiction)

The prologue is a section just before the novel begins that aims to set the stage and intrigue the reader about the story they’re about to read. Indeed, many prologues contain intriguing events that only become contextualized and make sense later in the story. For that reason, prologues are generally considered part of the body of the book, and not one of the paratextual elements included in the front matter.

Q: Are you #TeamPrologue or #TeamNoPrologue, and why?

Suggested answer

There can be the temptation, especially in the genre of fantasy and science fiction, to 'front-load' with the prologue. That is, to start with a chunk of exposition, setting out the geography and rules of your world. This, however, can be very dry. The reader will want to explore your world through your characters' eyes; this makes for a much more evocative experience whereas a history/geography lesson can make it feel like you're reading a text book, regardless of how complex and beautifully worked out the setting of your novel is. However, I'm not opposed to a prologue, as long as it serves a valid function in telling your story and is not just there to 'info-dump.'

As with all writing rules, there has to be some elasticity here. Prologues work well when they work well, and don't when they don't. When I'm editing a work, I don't automatically assume a prologue should be cut. Rather, I approach each prologue on its own merits. If I feel that the information in the prologue would work better gradually revealed through the course of the story, then that is what I'll suggest. So, in this, I suppose I'm #TeamSittingOnThePrologueFence.

Jonathan is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Tricky one! But honestly, I'm #TeamNoPrologue 90% of the time. Why? Because most prologues don't do much in story terms. A prologue only really works (and is therefore needed) if by the end of the story the reader gets a "ker-ching!" realisation about the prologue... perhaps they race back to it, and read it again, because now it makes sense, and adds something vital to the story.

I've worked on 300+ novels over the last eight years or so, and I've read a lot of prologues. My most common note on them: "Is the prologue needed? I think it could go. Just start the novel with chapter one?"

Ditto epilogues, actually. I had both a prologue and an epilogue in one of my novels. A reader who I know and trust told me my epilogue added nothing to the story: it didn't reveal anything new or additional. I was a little resistant to this at first. Months passed, and I realised she was right. I've since re-issued my novel without the epilogue, and it's a better novel for that deletion.

So weigh it up, and be honest about the role of your prologue. If you even have an inkling that it's mere baggage, listen to that instinct, and get rid of it. You can always put it back later if you change your mind.

Louise is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

It depends. Prologues, and specifically prologues that flash forward to a climactic scene later in the book, can sometimes be useful in cases where a novel starts slowly. Mind you, it’s usually worth asking why it starts slowly and what can be done to frontload more plot. But there’s a Hitchcock quote about suspense vs. surprise that I like a lot:

"We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let's suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, "Boom!" There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o'clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: "You shouldn't be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!"

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story.”

To my mind, the best use of a flashforward prologue is one that plants that metaphorical bomb under the table. You give away something that will happen later on in the story so that the reader will A) want to know how it happens, B) feel an increasing sense of suspense and dread as we see things starting to line up toward the preordained scene, and C) be looking forward to finally getting to that scene so they can find out how it resolves.

Nora is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Echoing what others have said, this is a complex question. I love a good prologue--with the key word being good. Many newer (and sometimes even seasoned!) authors attempt a prologue that doesn't end up serving the story well. They either provide a bunch of backstory to set up the story (instead of just diving into the story and weaving in the necessary backstory where it's necessary) and end up confusing the reader or they drop us right into the action that we then go back and lead up to from a less intense/intriguing first chapter to that scene in the prologue. If the beginning of the story isn't compelling enough and that's the reason you're adding a prologue (to essentially make a promise to the reader), then it's time to go back to Chapter One and elevate it OR consider starting the story somewhere else with something more compelling. In my experience, most prologues don't need to be there. BUT I love to be surprised by a well-crafted one!

That said, an effective prologue will be short and frame the story. It’ll set the tone, the location, give us clues, give us something surprising to look forward to figuring out, etc. But above all else, it will make the reader curious enough to want to keep reading. It can’t feel like we're being fed a bunch of backstory or explanatory details, rules of the world, opinions, etc. It can't feel like information is being withheld either--and many times, that's what happens when the author is trying to be clever about dropping bits of information. There's a fine line between causing confusion and evoking curiosity. A good prologue is compelling; it grabs the reader and doesn’t let go. And at the end of the day, ask yourself these two questions: What is the prologue doing that the first chapter can't? Can the story make sense without the prologue? If so, cut the prologue and strengthen your first chapter.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I'm #TeamNoPrologue, and I'll give you a peek at why. There are two kinds of prologues:

Flash Forward Prologue

In the Past Prologue

In the first type, you jump forward to where the action is, to assure the audience that YES, good stuff is coming! Once you've hooked them with that, you can get back to the boring setup of who, what, and why that they need to contextualize the future action. But in the early 2000's, agents started wising up and thinking...you know what's better than having an action-packed Ch 1, then going back to the boring setup stuff? A story that's interesting right from the get-go! So I'd focus on designing the opening moments of your story to be fun to watch, while demonstrating what the audience needs to know.

In the second type of prologue, by definition, you're starting before the story gets going, in a bit of backstory that will become important later. The problem? You don't know why it's important until...later. So why would you want to read it now?

This is why my favorite advice is: Find the chase, and cut to it!

Think about the moment your story really takes off, and design the scene so we find out everything we need to know through the way that scene plays out! Instead of a chapter to show us your character is a party girl, then a second chapter where she has an alien encounter, show her passed out in a mansion full of stolen Slinkies from last night's party--then have the aliens abduct her right out of the middle of the wreckage. It's quick, it's bursting with show-don't-tell characterization, and it's fun to watch...no prologue required!

Michelle is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I am staunchly against prologues until I read one that works, and then I'm totally won over! In other words-- and unfortunately-- it depends.

While writing, I'd encourage authors to consider the advantage of labeling their opening section "a prologue" versus "chapter one." If they're calling something a prologue simply because it exists outside the normal timeline of the book's narrative, then I become dubious. I admire prologues which feel less like preambles and more like cannon shots. To me, "this prologue offers background information" is not sufficient justification. It needs to add something to the book beyond logistical context: intrigue, tone, voice, etc.

For example, right now I'm reading the novel The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft. The book begins with a prologue titled, "Warning: a note from the translator." This is not a literal warning from a real translator. Instead, it's a character within the novel explaining their point-of-view, their closeness to the book's subject, and the fact that "part of the plot is inspired by true events, and although I can't say which part... we live in Mongolia, which has no extradition treaty with Poland...." To me, that's super intriguing: an unreliable narrator immediately remarking upon extradition! Are they in trouble? What's going to happen in Poland? So while this prologue articulates some background information, it's equally concerned with tone, voice, and setting the plot in motion.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Depends on the book, of course, but in general, I like a well-done prologue as an intro to a novel. Sets it up, and can act as a strong hook for a potential reader when done right. Other times, though, when it meanders, it can be a detriment—I once deleted both the prologue and epilogue of a book, and the writer couldn't've been happier; he said it was exactly what it needed—ditch the setup, and don't overexplain the ending. But yeah, definitely depends on the book.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Like many answers when it comes to the craft of writing, the answer for me is it depends (I know, I know, a frustrating answer!) Prologues can be a swift way to draw readers into the story, giving vital information that can't be shown elsewhere. If they're too long, sometimes readers skip over them to get to the 'good stuff'.

When I evaluate whether a prologue is needed, I often look at a few things:

- Is it too long and can it be shortened while retaining the same information?

- Does this prologue contain elements that are vital to the story?

- Does removing the prologue change the story in any way, good or bad?

If the answer to that last point is no, then that's a good sign that the prologue can likely be cut or doesn't need to be there. When deciding on whether to include a prologue or not, ask yourself: Can the information in this prologue be shown any other way somewhere else in the book? Is this prologue a sort of pre-writing exercise for me as the author to help me get into the world and characters, and can be cut later? And, as I evaluate, if I remove this prologue, what about the book and story changes?

Sometimes you may not know if a prologue works, and I like to read through the book in its entirety before deciding on whether the book would be stronger with/without the prologue.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I don't see any need for teams here. It's a question for each individual book.

A prologue can build suspense, like a teaser; it could be a flashback or -forward. It may be pointless: for example, some writers will call their first chapter a prologue when it's just Chapter 1.

A developmental editor can advise on this: they may suggest adding a prologue by pulling out a section of text from a later chapter; or blending the existing prologue into the main narrative; or renaming it 'Chapter 1' ... Whatever they think works for the book, they will say, and the author can agree or disagree, because it's their book and they always have the final say.

Vicki is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

It depends, y’all! As an editor, I am on #TeamPrologue when the prologue serves an explicit purpose in the storytelling that could not be achieved otherwise. Does it create a compelling hook that could not be accomplished in a different way? Does it provide essential backstory, critical to understanding the story’s forthcoming arc, that would not fit anywhere else in the story? Is it presenting the overarching themes so that they will resonate throughout the entire novel?

I’ve worked on romances that have a backstory prologue that makes you feel for the main character in ways that could not be executed with another approach. I’ve worked on fantasies that have a bam-pow future-flash hook in the prologue that instantly makes the story a page-turner, a how-did-we-get-here? tale of suspense.

Ask yourself what the prologue is providing your story. If your manuscript can start in a simpler, more linear way, then maybe go with that instead. But I’m definitely #TeamPrologue if it services the story in a particular way that pulls at your heart strings, makes your heart start to race, or creates any other sort of heart-feels that get you to fall in love with a story.

Sandra is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Introduction (for nonfiction)

An introduction is a few pages that usher the reader into the subject matter. The intro goes over early events or information related to the main narrative, so the reader has a solid footing before they begin.

“What's the difference between a preface and an introduction? A preface is personal to the author, discussing why they wrote the book and what their process was. An introduction relates directly to the subject matter and really kicks things off — which is why it's part of the body, not the front matter.”

Chapters

Almost every single book has chapters, or at least sections, into which the narrative is divided. These chapters may not be designated by a chapter heading, or appear in a ToC; some authors start new chapters just by using page breaks or divide their text by a blank line. But if you don't use anything to break up your content, the text can seem impenetrable to the reader.

📏 To make your book more fluid and readable, learn more about how to master chapter length here.

Epilogue (for fiction)

A scene that wraps up the story in a satisfying manner, an epilogue often takes place some time in the future, relative to the events in the main chapters of the book. Alternatively, if there are more books to come in the series, the epilogue may raise new questions or hint at what will happen in the next installment.

Conclusion (for nonfiction)

A section that sums up the core ideas and concepts of the text. Explicitly labeled conclusions are becoming less common in nonfiction books, which commonly offer final thoughts in the last chapter instead, but more academic theses may still be formatted this way.

Afterword

Any other final notes on the book; can be written by the author or by someone they know.

Postscript

A brief final comment after the narrative comes to an end, usually just a sentence or two (e.g. “Matthew died at sea in 1807, but his memory lives on”).

Polish your book with expert help

Sign up to browse 3000+ experienced editors, designers, and marketers.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

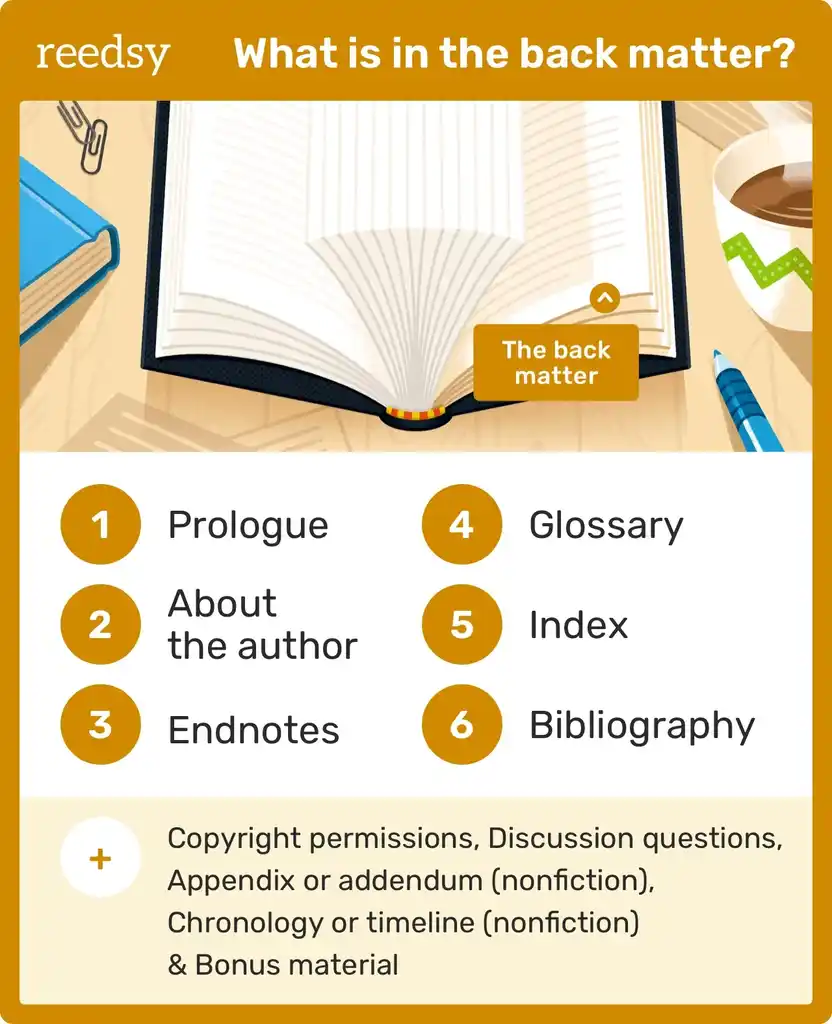

The back matter of a book

The back matter (also known as the “end matter”) is — you guessed it — material found at the back of a book, between the main body of text and the back cover. Authors use their back matter to offer readers further context or information about the story, such as endnotes or discussion questions, or even an excerpt from an upcoming book. But back matter can also be extremely simple: sometimes just a quick mention of the author's website or a note from the publisher.

Acknowledgments

A section to acknowledge and thank all those who contributed to the book's creation. This may be the author's agent and editor(s), their close friends and family, mentors and other sources of inspiration. The acknowledgments typically appear right after the last chapter.

George R.R. Martin’s acknowledgements in A Feast For Crows. (Image: Reddit)

About the author

This is where the author gives a brief summary of their previous work, education, and personal life (e.g. “She lives in New York with her husband and two Great Danes”). Sometimes, this is part of the front matter instead, perhaps even printed directly onto the backside of the paperback cover. Or, if it’s a hardback with a dust jacket, this may go on the back flap.

For more on this topic, read through our guide to writing an author bio or check out some stellar About the Author examples here.

Copyright permissions

If the author has sought permission to reproduce song lyrics, artwork, or extended excerpts from other books, they should be attributed here (may also appear in the front matter in conjunction with the colophon page).

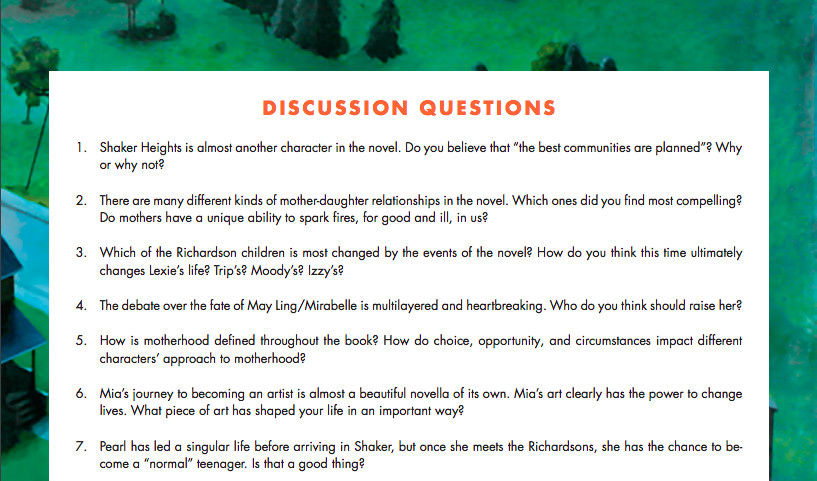

Discussion questions

Thought-provoking questions and prompts about the book, intended for use in an academic context or for book clubs.

Appendix or addendum (nonfiction)

Additional details or updated information relevant to the book, especially if it's a newer edition.

Chronology or timeline (nonfiction)

List of events in sequential order, which may be helpful for the reader, especially if the narrative is presented out of order. A chronology is sometimes part of the appendix.

Endnotes

Supplementary notes that relate to specific passages of the text, and denoted within the body by superscripts. Almost always used in nonfiction, but occasionally found in experimental/comedic fiction as well, such as Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace.

Glossary

Definitions of words or other elements that appear in the text. In works of fiction, the glossary may contain entries about individual characters or settings, made-up, or foreign words. The glossary usually appears in alphabetical order.

Index

A list of terms or phrases used in the book, along with the pages on which they appear, so the reader can find them easily. The index is also usually in alphabetical order.

Bibliography/reference list

A comprehensive breakdown of sources cited in the work. Your bibliography should follow a manual of style — luckily, it's easy to create one using free tools like Easybib. Note that this is a formal list of citations, not a bonus reading list on your subject; that would go in the afterword or appendix.

Bonus material

Some authors and publishers choose to include other bonus material in the back matter of the book. This can include interviews with the author or an excerpt of another book by the author, such as the first chapter of the sequel. This is especially common in paperbacks, as the author may have had time to write or even publish the second book.

FREE FORMATTING APP

Reedsy Studio

Format your manuscript for print or EPUB with a single click.

If you're ready to go a little deeper, head to the next part of this guide and prepare to get up close and personal with copyright pages!