Blog •

Posted on Jan 30, 2023

Live Chat: Offer Letter Writing Dos and Don’ts

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

View profile →Below is the transcript from our live chat on January 24th, 2023, where Reedsy’s Head of Operations, Prathima, was joined by editor Rebecca Heyman and designer Colleen Sheehan to break down the dos and don’ts of offer letter writing, combining insights from behind the scenes of the marketplace with the hands-on experience of two freelancers with great track records of winning project bids.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Offer letters should manage expectations

Prathima: A lot of what I do as Head of Operations at Reedsy, is help freelancers convert their offers into collaborations, and mediate disputes about things like quality of work or cancellations. Disputes often come back to how the offer letter was presented, so today we’ll have a look at how to avoid that by managing expectations.

Make sure you check out our Freelancer Profile Critique webinar as well, where Prathima breaks down how to optimize your profile for the marketplace.

Martin: Prathi, based on your experience, could you tell us a few things about what makes for a good offer letter?

Q: Can you share a tip that helped improve your offer letters?

Suggested answer

Make the client feel special, (because they are!) Don't treat them as a dollar sign, treat them as a human being.

Chad is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Prathima: Sure! The first thing I’d like to recommend freelancers is to send your offer quickly. I find that when authors make requests, they're looking for an offer as soon as possible, so sending your offers within four working days is always a good idea.

Secondly, you should tailor that offer letter to the author's needs as much as possible. It can be something as small as referencing their manuscript, like a couple of lines that you like. Or, if you're an editor, you can do a couple of sample edits. These small things show that you have put in the extra effort, and make a huge difference.

As for deliverables, I would shy away from saying that I'm just doing “editing”, or “designing,” and I’d be more clear and specific about the services I’m offering. Authors have different expectations and terminology, so it’s a good idea to explain what you mean by, for example, an “editorial assessment”.

If possible, you can also add milestones with each payment, detailing what you’re going to deliver and when, as well as if there’s a payment attached to that.

Lastly, I find that a lot of freelancers forget to include what they expect from the author. When are they supposed to get back to you? What is their deadline? A lot of these things affect the completion date.

☝️ Don’t forget to include what you expect from the author if there are deadlines affecting the completion of the project!

Martin: For those who aren't embedded in the Reedsy sphere, at what point of the process does the offer come in? What will the freelancer have received before they make their offer?

Prathima: Freelancers will have received a request — an inquiry from an author with details about the manuscript, a deadline, or, if it's a design project, details about what exactly the author is looking for, and perhaps a sample of the manuscript or other details about the book.

Martin: Alright. Now, let’s look at some sample offer letters from our marketplace.

FREE RESOURCE

Offer Letter Checklist + Template

Follow our tips to successfully sell clients on your services while setting clear expectations.

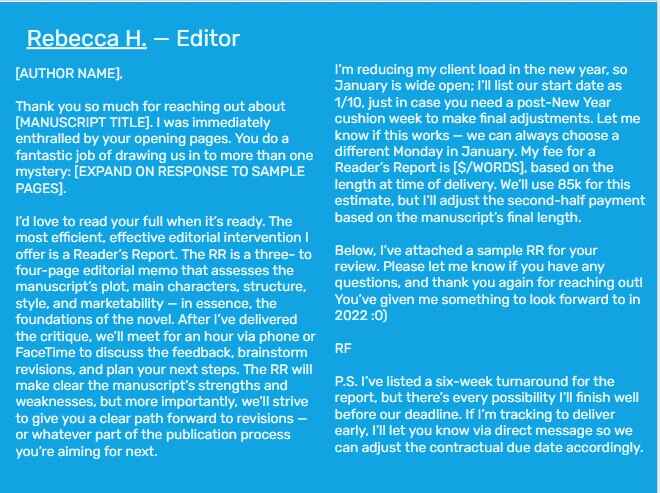

Offer letter #1 — Rebecca H. (Editing)

Rebecca: This is, for me, a fairly standard offer letter for the service I provide most frequently on Reedsy, which is a “reader's report”: a type of editorial assessment, which does not generally involve line level edits.

To Prathima’s point, I’m being really specific about what I’m going to deliver and, in some cases, what is excluded.

Obviously, I always start by personalizing with the author’s name and thank them for reaching out about their title. Then I give some genuine feedback. In this case, I really was enthralled by the opening pages, so in the bracketed portion, I was giving examples of the kinds of questions that came to mind.

This doesn’t just show the author that I've read their pages, but also how my brain works, which is really important. If the questions I have about their opening pages have never occurred to them, or are not questions they care to answer, we're not going to be a great fit. So, in all these little ways, you can start to show your author who you are as a freelancer, and that’s going to help you establish and set accurate expectations, which really is the name of the game in an offer letter.

Q: How do you personalize your offer letters to show prospective clients that you've engaged deeply with their project?

Suggested answer

In the opening paragraph I may share one or two things that come to mind for great book cover ideas to show that I have read the details about their book in their Request. I have seen that most authors desire working with someone who believes in the success of their book and acknowledges the hard work that was put in to make the novel happen.

Candice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The author had indicated that their full manuscript wasn’t ready yet and I don’t look at partials, so I also said that I’d love to see the full version when it’s ready. Then I describe the reader’s report so that, if they are looking for line level edits, grammatical feedback, or somebody to finesse their sentence structure, they can tell that this is clearly not the service for them.

“After I've delivered the critique, we'll meet for an hour via phone or FaceTime to discuss the feedback, brainstorm revisions, and plan your next steps.”

I've been a freelancer for a very long time, and I cannot say enough about how valuable a post-deliverable call is. When you’re working on the edits, there’s a one-way conversation and opening yourself up to making that a two-way conversation with your author leaves people with a great feeling. You're more likely to secure future business from this person if they have a feeling of connection to you and if you can sort of bring yourself off the page. I don't know if this sets me apart from other freelancers, but it's a service that I have always included since the beginning of my career, and I've never regretted it.

“The reader's report will make clear the manuscript strengths and weaknesses, but more importantly, will strive to give you a clear path forward to revisions or whatever part of the publication process you're aiming for next.”

I find it’s really important, especially on Reedsy, to let people know where they'll be at the end of your project. I don't want anybody to think that they're going to be ready to hit ‘upload’ and publish their book after a reader's report. That's absolutely not the purpose of this service. So, again, in small ways, I’m establishing a clear expectation that I feel confident I can deliver.

Then I talk a little bit about my workload, when we can start, and I mention my fee, which is per word. Importantly, I tell them that I will adjust the second payment according to the final word count.

I’ve had more than one author tell me that they're going to send me a 75,000 word manuscript and then they send a 95,000 word manuscript. They're amazingly surprised that that costs more money, so I always state that this is a per word price and I will confirm the word count at the time of delivery in a message. If any adjustments need to be made to the second half payment, I let them know that there could be some wiggle room. For my fellow editors out there, I also find that emphasizing that I charge per word is a great strategy to encourage people with very bloated manuscripts to do some self-editing before they send it my way to get the word count down.

Since you can't really sample edit a manuscript report, the feedback I give in the offer letter is my nod to that. But I do provide a sample letter, to give them a good idea of my editing style. It shows authors how in-depth the work gets and reiterates everything I've mentioned in the offer letter. Since a lot of authors find me via the First Line Frenzy, giving people a sample letter helps them understand that I'm coming to their work from a very professional, quasi-academic place, so they don’t expect me to go “Hey Bestie, this is why I loved your book.”

Lastly, I have a little postscript. I list a six week turnaround on most of my editorial letters, but sometimes I finish early, depending on my workload. But I can’t deliver early and expect to be paid immediately, so I always like to leave a window open on scheduling, never for me to be late, but for me to be early. But you can't always assume that people can pay earlier than specified, so I add this as a courtesy, in deference not only to their financial planning, but to let them know that there is a chance they'll hear from me early.

Martin: Is that standard, Prathi?

Prathima: We always schedule the last payment on the completion date, so yes, that's where the last installment is set automatically. I always recommend splitting it up into one or two payments and to always ask for an upfront. And maybe keep the last payment to the completion date.

Note: If you and your client agree to change the delivery and payment date, you can make an amendment to your collaboration according to both of your preferences.

Martin: We have a question in the chat. Would you say you're enthralled, even if you aren't? Is flattery effective?

Rebecca: No. I never lie about these things because we are talking about establishing expectations. If the writing doesn’t appeal to me at all and I can’t see myself connecting with the project, I don’t take it.

There was a time in my career when I took everything that came my way, and I understand a lot of people are in that position. It's a tough hustle to take work that doesn't move you, but I will always give honest feedback. If I'm not intrigued by the writing in the sample, I generally decline.

FIND CLIENTS

Grow your business on Reedsy

Submit your application to join our curated network and connect with clients.

How long do you spend on each request?

Rebecca: This will be surprising, but I write all of my offer letters from scratch and don’t use a proposal template. I think this keeps me very sharp and forces me to pay attention to each individual project.

I only accept about 30 to 40% of the work that comes my way so I feel that if I allow myself to use a template, I risk losing some of the sharp precision of my offers. This is specific to editing. Later, you're going to see Colleen's offer package, which is huge and detailed and incredible, and it would be totally impractical to do that from scratch [without a template] for every client.

For my work, I’m going to read no more than 3 to 5 pages of what gets sent through. That takes me a few minutes and, if I’m interested, I’ll usually circle back to it when I’m writing the offer letter to pick out a couple of details I’m keen on. Writing the proposal itself takes about 10 minutes. I know what needs to go in it and some of it is rote. Even though I'm not copy-pasting anything, I obviously know what is in a reader's report and I have used the same sentences many times.

Then I make sure to check my calendar and do some math, trying to give as much information as possible. There is sometimes an intermediate step of asking some clarifying questions when a request comes through, too. So, grand total, I try to spend no more than 20 minutes on a proposal. I've written a lot of proposals, so it's going to take a little longer if you're newer to this.

I also want to add that you need to factor in the time it takes you to do the proposal in your price. It’s the cost of doing business, and you need to make sure you're getting paid for that. If you're spending 3 hours a week writing proposals, you need to adjust your pricing accordingly to ensure that you're compensated for the time it takes to prepare.

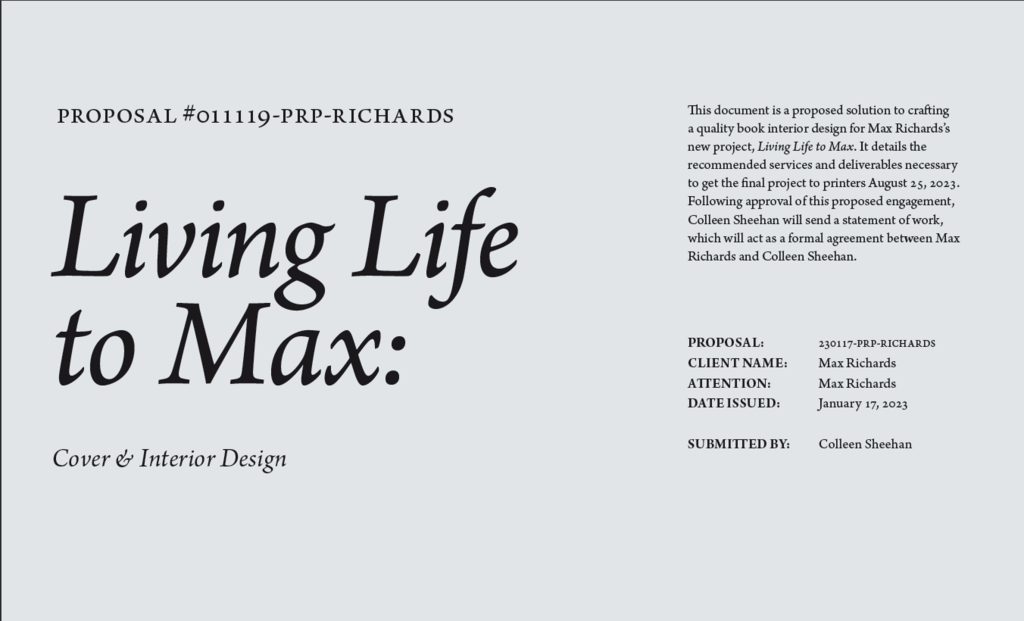

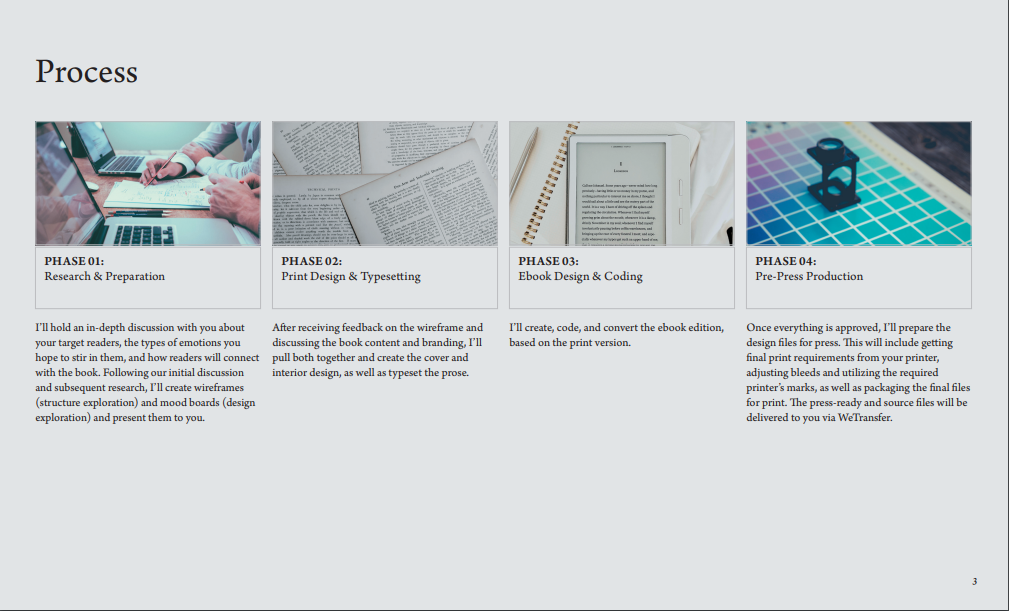

Offer letter #2 — Colleen S. (Design)

Colleen: I'm also at the stage of my career where I can choose what I want to do and I have a preferred set of standards that my clients need to meet. They need to be looking for full package design — both cover and interior. Then I will also do some market research for them, specific to the design because it's helpful for authors to learn where they stand in the market. Lastly, I also do project design and some illustration.

I prefer to work on books that need all of that. If I'm getting projects that don't, I usually just reject them right away. That's about 62% of the inquiries that I get.

My proposals don't start with the proposal. First, I send them a templated response: “Hello [their name]. Thank you for inquiring about your book,” etc. That helps build recognition and trust, just like Rebecca was saying.

Then, I set up a call with them, which takes at least 15 minutes. But if the project is one I’m going to take on, it probably lasts for 30 minutes or up to an hour. A good conversation usually means we’re going to work together and I can get a good feel of that from the beginning. After the call, I send them my proposal:

Basically, my proposal is set up to explain the process so they know what their expectations are. Then, at the end, we get into technical details like timeline and pricing. By this point, we have already had that call that could last an hour, so I’ve gotten all the information I need for this proposal.

The next page is a basic outline of the process with simple explanations. Nothing too intense.

On the following pages, we go through each phase a bit more in-depth. My official proposals tend to have more pages than this, but this is essentially what it is. Phase one gets at least one page discussing what we're going to be doing, phase two gets one page, and so on. I always put the deliverables at the bottom so the client feels like each phase has a conclusion, which is important. We’re not in the weird ether of “where are we and have I received these files yet?”

My projects tend to last five weeks from manuscript to finished product, including upload. Everything here is estimated, because life happens and, for some reason, it always happens in the middle of projects. Giving an estimated duration keeps everyone feeling like we know where we're going, but if something comes up, it's okay. There's some forgiveness, which is good to have on both sides as long as it's agreed on before you start.

Lastly, I have the budget where I break the pricing down per phase and then the whole package price. This prevents people from trying to nitpick to get the price down because none of these phases can really be dropped. It also means that they can’t try to compromise on the quality of my services. The client is on-board with what we’re doing and that it’s a completely different kind of project than just the basics [from the start]. It’s really in depth, and the price reflects that.

Pros and cons of pre-project calls

Martin: We encourage freelancers to send their offer letters as soon as possible, but what about when you need to communicate a bit more before making an offer? How can freelancers navigate that effectively?

Prathima: Quite often, just like Colleen does, freelancers set up a call. And we do encourage that for professions like ghostwriting because it's a longer project with a huge investment of time and money. So freelancers can always do a phone or video call over Zoom or Google to establish early contact if they’re not sending an offer letter immediately.

Once you’ve had the conversation, we advise you to always recap it as a message because you want to make sure that there’s a written record of your agreement. It’s also a good idea to summarize it all for the client. And then you can make the offer as quickly as possible after that.

Martin: Have you seen any cases where an author pitches different freelancers and one of them immediately sends an offer letter while the other wants a phone call, so the author chooses the former because it seems easier?

Prathima: It does happen, but it depends on the offer and what the author's looking for. Is the freelancer exactly who they want to work with? Does the portfolio match what they're looking for? Is the offer detailed enough?

It also depends on the profession. For something as design, you probably do want to have a conversation to make sure that your style is exactly what they're looking for. That might not be the case for editing, where you may prefer to have a conversation at the end of the collaboration instead.

Rebecca: I saw a question about having a call before an editing collaboration in the chat and just wanted to comment on that.

I think it’s perfectly acceptable, and I have done them in the past. However, at this point in my career, I’m not an editor who's doing a ton of handholding. I'm not offering coaching services with a lot of one-on-one time, so I tend to put conversations with me behind a paywall.

When I do pre-project calls, I put a very clear time limit on them and I’m not as generous as Colleen. If I say 15 minutes, I’ll give them a heads up at the 13-minute mark because I have to protect my time. It's very easy to get wrapped up in the rabbit hole of answering questions about publishing and “please just look at my first line.” I'm not a therapist and I'm not a writing coach, unless that's what you've hired me to do, so I do try to give as much information as I can in these proposals because I could lose a ton of time every week if I gave all of my potential clients 15 minutes.

If you want to protect your time by not making contact in advance, I think you need a really strong portfolio and an extremely clear proposal. Obviously, editing is much more cut and dry than design; there's not a ton of collaboration when I am reading a manuscript and giving feedback, whereas collaborative design is something totally different.

I don't think there's a better or worse way to do it, but for a lot of editors, you could end up losing a lot of time that you'll never get paid for if you give everybody a pre-project call.

Colleen: I agree. And I have to say, too, that the reason why my rates are high is because I do all of that work on the phone. People who contact me get at least 15 minutes if I don't outright reject them. But I do reject 62% by just looking at their brief, so it's not like I do this with every person. I absolutely do not. I wouldn't have the time.

Then, during the collaboration, there's a call on the first day of the first week, the first day of the second week, and usually one or two more calls at the end. If I do project management, one of those calls is about teaching clients how to upload books to a distributor, which is expensive to do.

Not all designers do it like me, so you have to look at your process and make sure that all of it fits. Definitely don't do something just because you saw someone on a Reedsy Live doing it that way, because it might not work for you.

Assessing who to decline and who to make an offer to

Colleen: The first thing I look at when an author sends a request is whether they want only cover or interior design. Since that’s not what I do, that gets rid of probably 50% of the people who contact me. For the rest, I look at whether the topic interests me, and if it fits within my timeframe before I decide to have an actual conversation with a potential client. If I’m not interested, I just click one of the premade options to decline the request.

Out of the total inquiries I've had since April 2021, I close out 62%. Authors do something else 13% of the time without even talking to me. 3% of the time I’ve had the whole conversation and they say no anyways. Then I get accepted 16% of the time.

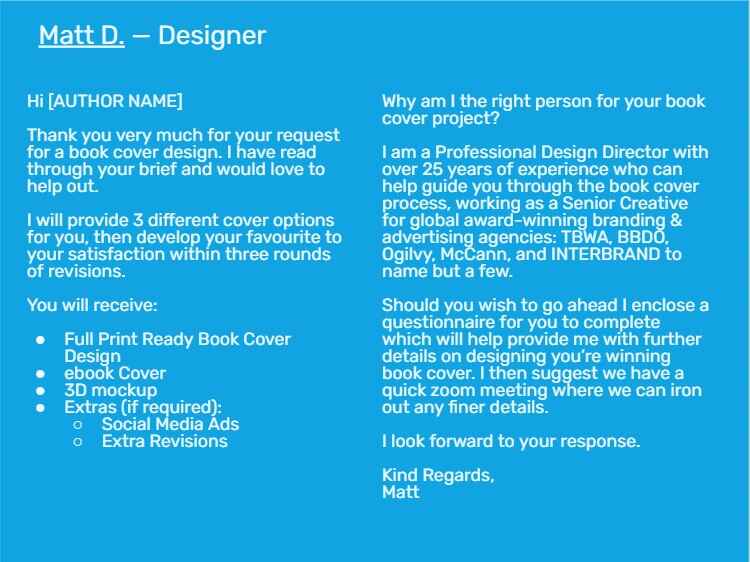

Offer letter #3 — Matt D. (Design)

Rebecca: This is obviously someone who knows what their process is and that's very comforting to an author looking for these services.

One thing to always keep in mind is that we are often dealing with people who are on a massive learning curve in terms of what editing and design is, so doing a little bit of teaching in your proposal can sometimes really help your author determine whether or not they need you and save you some trouble.

I like the way Matt acknowledges their author in the first paragraph, but I’d be super wary about editorializing other people's experiences. For instance, “I will provide three different cover options for you, then develop your favorite to your satisfaction within three rounds of revisions.” I can’t determine when my client will be satisfied with my work. So I would probably say something like “I will develop and refine your favorite cover over the course of three rounds of revisions.” Because what if you get to the end of the three rounds and the author is not satisfied. You said you would do it to their satisfaction, and that leaves the door open to disputes.

I sometimes look at disputes with Prathima and the number one thing that comes up is that if the offer letter were clearer, there would never have been an issue. Ambiguous language of any kind has no place in your offer letter.

Colleen: One of the ways that I get through a lot of what Rebecca just talked about is through that conversation that I have with potential clients.

I position myself as a market-conscious book designer who does market research before I actually get into the design. That helps weed out the people who are looking to be satisfied and then pick favorites, because this is not about favorites; it’s about selling your freaking book. Sometimes we're going to do stuff that isn't necessarily your favorite, but is right for the genre. And I create that expectation on the first call. Then I don't have to get into this kind of thing.

I saw someone mention that they hate doing calls in the chat, and I’m definitely like that too. But you can’t replace the communication that comes with a face-to-face conversation with a letter. It helps you avoid these issues where you hone in on the wording in the offer letter.

The second thing I see in this letter is that there's too much about Matt himself. Even though you absolutely need to build trust, in the offer letter, they want to know how you’re going to give them a good cover.

Martin: Yes, authors appreciate when you focus on them and their project, for example by personalizing the first paragraph, even talking about the general feel of the design, perhaps, or acknowledging the nature of their book and focusing on what they’ll be receiving from the design as a product.

Colleen: Yes, and any information about you as a freelancer can go in your profile overview. This is the kind of stuff that convinces authors to contact you in the first place.

Prathima: For design, I would probably also include something about copyright. This is something that comes up in disputes. If you don’t want to give up the copyright, you could mention that in the offer letter and add special terms in the contract.

According to our standard terms, once the author makes a full payment, all the rights go to the client. But if you just want to license it out, you have to make that clear. If you're going to use stock images, clarify whether the author's going to be the one to pay for that. Are you going to be sharing source files or not?

These are things that designers need to be a little bit more detailed about, and almost approach as if it were a legally binding contract. Especially when you're illustrating a big picture book, you probably want to keep the copyright. This helps manage expectations, which is what offers should do.

Offer letter #4 — Leila S. (Marketer)

Colleen: I see a lot of detail, which is great because most people don't do a lot of deliverables, and it's kind of up in the air what you're getting. But I don't see a lot of personal connection. I hate to sound like a broken record, but that's what builds trust. If I sent you an inquiry and you just shot me back this, I'm probably not going to work with you because I feel like a robot just threw something at me out of a ChatGPT.

The complaints I get from authors is that if you don't connect with your designer, the communication is really hard and then you tend to fall out more often because that initial connection just isn't there. Amazingly personable designers who do bad work make more money than amazing designers who can’t talk to you or communicate with you.

But this is a marketing plan so maybe it isn’t as important in that sphere, even though marketing is all about people-connection.

Rebecca: Obviously, this is not my area of expertise but, from my perspective, it looks like this person is going to deliver a lot of pre-fabricated content. When I see things like Amazon, LinkedIn, and Facebook advertising rundown, along with a quick training guide, it feels like you’re telling me that you've already produced these materials and I am paying you to send them to me. It feels like this is a rote, impersonal offer.

At the same time, let's give Leila her credit where it's due. A metadata, keyword, and blurb audit is about analyzing what exists and sharing feedback based on expertise. A marketing plan is not saying, “I'm your PR person,” it's saying “these are strategies that you can implement in your own marketing.” So I don't know how personal this needs to be, but it feels very impersonal.

Even an opening paragraph that says something about the project or “I'd love to hear how you find books,” or “what social media outlets are you already using?”; a bit of two-way communication would be really nice. But, overall, I'm not sure how much interaction is involved in this so I don't want to give the impression that the only way to be a successful freelancer is to make personal connections with every single person who asks. It’s not always about being best friends.

This feels very cut and dry to me. And that might work for some authors, but I think you are going to catch more flies with honey and certainly you're going to catch more authors by engaging with them about their work.

Prathima: Very often, freelancers do send a message out before they send this type of offer letter, so usually the offer goes with the message or it goes out after the message. They probably would've had a prior discussion about the author's expectations and objectives, their manuscript, what they're looking for.

With this type of letter, it would help with a message and having had that discussion before you make an offer. It ties the personal relationship that Rebecca is talking about with an offer with very clear deliverables and deadlines, which I really like.

Jargon in offer letters

Prathima: Another thing that I was going to bring up is that with an offer like this, without having had prior communication, you assume that the author knows what you're talking about.

Martin: That may work. You throw out enough words and people go “I guess I'll need what you're selling.” But, on the other hand, the marketing plan feels a little bit on the vague side.

Colleen: I do this stuff on the side for people sometimes as an extra and the deliverables are often simply [a conversation about strategy and about audiences]. Then the offer is only half a page because you just need to summarize it really fast. So the person already knows the deliverables.

Martin: Someone in the chat said the issue with marketing is that folks might not know what's reasonable. It's hard to balance the pragmatic steps you’re going to take to market your book without promising a bestseller.

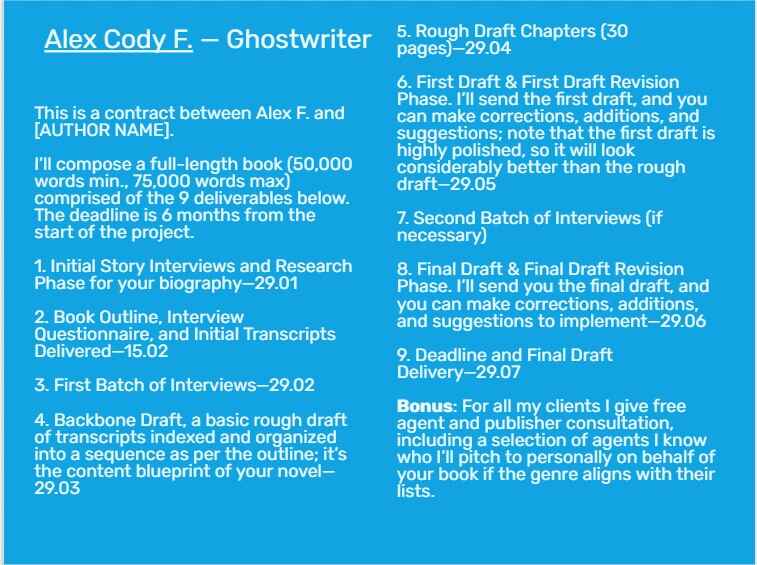

Offer letter #5 — Alex Cody F.

Rebecca: I hate that bonus. I never say that I have agents in my personal network and that I'll help you pitch because you don't want to be elbow deep in a manuscript that has fallen apart completely in act two and know that the author is expecting you to introduce them to an agent.

I think giving agent and publisher consultation is fine. But I wouldn't say anything else really. It's a very gray area where I wouldn’t pitch on anybody else's behalf; it’s the work of the author to pitch their own book. So, I dislike that idea a lot.

It's another thing to say that you have some literary agent connections, and if, at the end of our project, it feels like I know someone who might be able to represent an author, I'd be happy to make an introduction. But your author is going to hear that and think “oh my God, they're going to introduce me to an agent.”

You're saddling yourself with more pressure than need be, especially if you're not being paid. And not that you should be paid for introductions, but I think this just takes it a step too far. I’m very conscious of language around making introductions and connections because there are no shortcuts. The publishing journey is not going to be easier this way.

Colleen: This is about as non-personal as the previous letter though this is clearly being treated like a contract, so that's different. They’ve probably had a bunch of communication before this, or else you wouldn't even know what they're doing here. So that part looks okay.

I feel like it could be organized a little bit better, but that's stuff you learn as time goes on.

I also agree with the bonus. Something that a lot of freelancers do, especially designers — and that's my perspective — is that they don't value the mental labor that goes into stuff like that bonus. That's a lot of work to do. I would never do that for anybody, even if I had the option, unless I was paid for it because it's practically like being an agent. Maybe I get a percentage of something, but it's hard to do because you have to love that book to pitch it.

I know he's a ghostwriter, so he has written the book too, and maybe that's an extra incentive for himself, but I do feel like that's an offer that is hard to put money on.

And a lot of people will get an obnoxious feeling from something like that. Anything that suggests that you’re going to do a lot of things for free is not a good position to be in. There's a point where you need to think about how much work you're putting into things and how much money you could even make on that. Because intellectual property is a big deal.

Prathima: I'm not going to pick at the bonus, but I would have liked to see what the ghostwriter’s expectations of the author are. The letter clearly lays out what Alex is going to deliver during each phase, but what exactly is he looking to get back from the author? Does the author have a deadline? Do they need to get back to him with their interviews, biography, transcripts, or questions?

That's probably the only thing that I find is missing. I'm not sure if they've had that discussion before in a message, but it would be nice to see that tied into an offer, especially with something like this, which goes on for six months.

Q&A Session

How do you deal with clients who expect your time?

Rebecca: I put my time behind a paywall. When I'm coaching a client, we talk every week and they can email me anytime if they're stuck.

Frankly, one of my post-project strategies to keep the door open to future business is that I always say that I’m happy to look at a one page synopsis anytime if they come up with something new. Because that’s a low time commitment and I put a clear parameter around how much time I'm willing to give free of charge. I consider it an investment in future work because it's probably going to come back to me. So I’m happy to give my time when I'm compensated for it.

If we complete a project together and I enjoyed the project, I will say, “if you get stuck, email me.” I'm always happy to see an email from a client. And then, if they need a call, I have an hourly consultation rate, and they're welcome to pay it.

It’s very easy to undervalue your time as a freelancer, especially if you work at home. There's less friction between your work life and your home life, and that can make it easy for it to bleed together. I don't answer emails after 5:00 PM, I don't put proposals together on the weekend. Those are not working hours for me.

Protecting your time will help you remain kind to your clients because you won't feel taken advantage of. I'm here for the people who pay me to be there for them. I don't owe anybody anything that I'm not being compensated for.

How do you explain why you’re doing market research and what kind of research you’re doing?

Colleen: That's taken care of in the overview stage of my profile. [Explaining my process there] helps weed out people who ask that question because they can read that and leave if they're not interested in the service.

But if someone did ask that, I’d say it's marketing research for your project in terms of design. It’s looking at the bestsellers in your category and seeing what the readers say sells, which is the covers that are the most popular. I also look at how they structure their interiors or the themes that we can see across multiple books that are selling well. Things that really help inform the design.

In my process, the research and design phase also includes wire frames and mood boards, which helps make decisions and get input from the author before I even do any work. So by the time they get three custom ideas from me, they recognize that that’s exactly what we talked about. They know why we're doing this and why we're going in this direction. That helps keep things down to three revisions too. I almost never get people asking for extra revisions anymore. I used to, before I started doing it this way.

Pros and cons of working in-house vs. freelance?

Rebecca: I think the pro of working with a publisher is that you're not educating people about what you do. They know already and they have reached out to you because they like what you do. But you sometimes have less wiggle room on pricing. You cost what you cost, but you don't know what the internal budget for any given project is or why they're reaching out to a freelancer.

I find that my individual clients want more of me, the person, not just me, the editor. Sometimes that's nice and sometimes it's too much. Working with publishers is sometimes preferable because they just want your work and they want it delivered on time.

There's definitely a plus and minus for any project that you're going to take on. In some ways, the uptake on a publisher-driven project is much less. The time investment is much lower in terms of winning that business because if they're coming to you, they probably already want you.

What was your process of figuring out your rates like?

Colleen: Oh boy. I did my first job for $25. That was in 2014. It took me two weeks.

What I've done is basically every two months, I raise my rates by around $500 and right now I'm trying to see the ceiling for what is acceptable and what isn't. And when I hit that ceiling, then that’s where I’ll be.

I've tried to do big jumps before. It doesn't work for me because I get panicked. But if I'm just adding a bit every so often, I'm used to it after four times. It's much easier on me psychologically, which is really the whole point of freelancing: how can I be easier on my own brain?

FREE RESOURCE

The Full-Time Freelancer's Checklist

Get our guide to financial and logistical planning. Then, claim your independence.

I say, start where you are and just keep raising your rates. If they're too low and you’re doing what I was doing when I was charging $150 for a complicated non-fiction book interior, raise it faster. Each new project is an extra $300. But once you get into the 3, 4, or 5K range, I think every $500 to a $1000 raise is good to see how the waters are feeling at that point.

Rebecca: I have never charged an hourly rate because I don't want to be penalized for being fast. I also don't want to keep a time card. I charge by the word. That can get tricky in a multi-phase edit because sometimes people can see a price tag per word that seems really high, but you have to consider the number of hours that you're going to be spending inside the manuscript.

It's really hard when you're starting out. It's hard for everybody to determine what value is. You can come at it from the backend by saying “what is your cost of living?” “How much money do I need to make per month?” “How many hours do I have to work?” “How many words can I read per hour?” Then you're going to arrive at your rate.

There have been times in my career when I was working seven days a week, and my husband, who is a financial advisor, told me it was time to raise my rates and price out some of the people who wanted to work with me. That’s how you get to a place where you can take less work for the same, or more, money. That comes with time.

In the beginning, you're panicked, you're scrounging, you're afraid the work won't come, so you say yes to everything. You keep your prices low, you try to win the business because it's cheap. But instead you should win the business because you deserve the business, because you're the best, and not because you underpriced your competitors.

It's not easy, but you have to value your brain, your services, and your input, and find the number that reflects that value.

Also, if you ever find that you're really bitter about getting to your desk every morning, your prices are too low. If you find yourself thinking “oh my God, this thing is how many pages?!” you didn't charge enough, and that's on you. You don’t get to be salty and angry about a project that you didn't realize would take so much time if you didn't put in the research to figure out what the project would need, and now you're stuck doing it for a lower price. Like jokes on you buddy, you clowned.

Colleen: Can I add something to this? Because that is completely and utterly true, but also, if your prices are low and you are in that place, can you forgive yourself for two seconds?

You've never done this before. You need to build the experience, not just of doing the work, but of how to run the freaking business. I don't have a financial advisor as a partner, so all I got when I was at that stage was “you’ve been working 12 hours per day every day for the last 5 years. If you keep doing this, we’re having a problem.” That’s how I got told that I was doing too much.

You have to get to that place over time, but the whole point is that you’re constantly moving forward and don’t feel bad about yourself when you’re not there yet, because that doesn’t help.

If you're receiving a lot of requests, but not closing out sales, what is the first thing you would try changing?

Prathima: The rate is probably not the right place to start. To answer that question, I’d probably need to look at your specific profile to see what's happening. A lot of it depends on what's written in your profile and what you write in your offer.

Is your offer tailored and detailed enough? Are you making sure that you've read the manuscript or sample? Does your portfolio match what they're looking for? A lot of people don't take into account whether their profile matches what they offer.

Those are the, probably the first couple of things that I would look into to start optimizing your profile as much as possible.

Colleen: Something that has helped me with my profiles and my copy is that I think about everything from the author's point of view, as a system. So the tagline always feeds into the bio, and the bio always feeds into what's in my portfolio. All of those put together always feed into that first conversation we have.

It’s not just setting up expectations and trust, it's also getting rid of the people who aren't interested. If you're getting to the point where you're writing proposals and like 50, 60, or 70% get rejected, it's because they don't see the logic of why they would go to you from the very second they see your tagline in the marketplace.

So really, figuring out how to condense all this stuff and move it into your profile is really important. None of it is separate from each other.

How do people find out about your services?

Rebecca: I started back when writing Twitter was, like, 50 people and people were looking for someone who could edit. At this point, people know about me because I put myself out there. I run a daily writer-focused event on Instagram, and I come here live and I let people know about me too.

I think one of the greatest gifts that Reedsy provides for new freelancers is a professional landing page so you don't have to have a whole website. You can just rely on Reedsy, which is very beautifully designed and straightforward and professional.

If you're an editor, you need to go to where the authors are and let them know that you exist. Keep putting yourself out there, keep engaging, talking, asking for help when you need it, tapping into your network, and letting people know what you do.

Colleen: I have an agency and I have Reedsy. They're in two different areas, but Reedsy’s search system is so good, because not only do they take into account the books you put in your bio, your tagline, and what you specialize in, but also they [pull data from Amazon's API] of the covers you put in the portfolio. Really, what it does is it does excellent SEO for you. You don't have to do anything, except put the right words into your stuff.

Rebecca: That's amazing. I love Reedsy for many reasons, but I didn't even know you guys were doing that. That's great.

JOIN OUR NETWORK

Supercharge your freelance career

Find projects, set your own rates, and get free resources for growing your business.

What’s one piece of advice you could share with your younger self when you first started freelancing?

Rebecca: For the baby editors out there, there is this expectation that we put on ourselves, and that authors put on us, that we will always be right. You're putting yourself out there as someone who can correct mistakes, but you’re not always going to be right, so you have to learn to be wrong with grace.

It's part of the learning process. You'll get better as you go, but you're going to make mistakes and you have to own that. That might mean leaving a door open in your contracts. For a long time, I put in all of my line editing contracts that I recommended that clients get a proofreader after our collaboration to catch any inevitable human error.

I’m a human being who will make mistakes, and in editing there's this weird culture that we have to be right all the time. We can never make a mistake. But that is not what it is to be human, doing human work. So you have to just give yourself grace and accept that you don't have all the answers.

Colleen: I’d say, don't work 16 hours per day for the first 5 years, 360 days per year, because you will probably put yourself in the hospital, or you'll lose a relationship, and it's not worth it.

And also, always keep learning. Don't get stagnant. Not just when it comes to the design skills; what's more important is your own process and how you do things that give consistent results to people. Experiment, because you don't know what’s going to be the thing that helps you. You have to learn and it's going to take a while, so just keep going.

Martin: Great, thank you to Prathi, Colleen, and to Rebecca. See you all next time!

For more tips on how to showcase your experience, get more freelance clients, or notifications about events like this, subscribe to our Freelancer newsletter or follow us on LinkedIn.