Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Rising Action: Definition, Tips, and Examples

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →If a story were a rollercoaster ride, the rising action would be the thrilling climb — when your heartbeat quickens in anticipation, the stakes rise, and you can’t help but wonder what awaits you at the top.

Simply put, the rising action is the driving force behind almost every story and makes up the majority of most story structures. But just because it’s essential doesn’t mean it’s easy to nail!

In this guide, we’ll break down what should happen during the rising action, share some examples of it, and some tips for using this crucial element of plot to its full potential.

What is rising action?

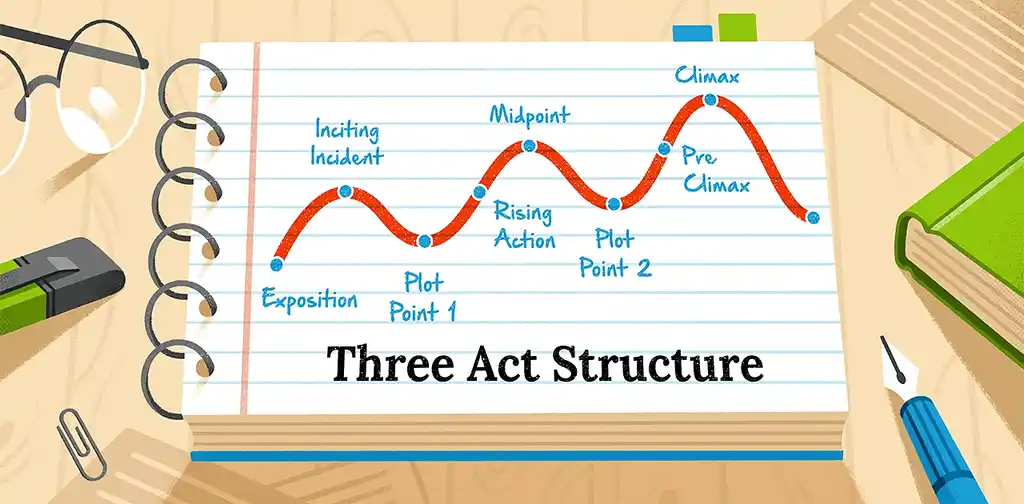

Rising action is everything that occurs after the inciting incident and before the climax, thus forming the bulk of the narrative. As its name suggests, the action increases throughout, heightening the tension in the story until it builds up to the climax.

Meanwhile, the direct opposite of rising action is falling action, which follows the climax and de-escalates the tension in the story.

One of the most important things the rising action accomplishes is delivering on “the promise of the premise,” which is the story that readers expect. In a mystery novel, the rising action would be the detective trying to crack the case. In a romance, it’s the main characters falling in love.

But there are a few other things that a well-written rising action accomplishes.

It develops internal and external conflicts

Just about every story fundamentally explores characters dealing with conflict. Specifically, they must contend with two types of struggle:

- External conflict, where someone or something prevents them from getting what they want, and

- Internal conflict, where the protagonist struggles with something about themself — a desire, fear, or some other internal aspect that they cannot reconcile with their larger personality, worldview, or current course of action.

A strong rising action sequence develops both these types of conflicts, ideally with multiple occurrences of each. For example, in a mystery novel with a detective hunting down a serial killer, her conflict with the unseen enemy will grow as she keeps on struggling to achieve her goal (external conflict). She’ll likely clash with the police force and the community too, as people grow frustrated with her lack of results (more external conflict).

At the same time, the protagonist should also undergo some sort of personal difficulty — an internal conflict that stands in their way. In that mystery novel, perhaps the detective suffers from a crisis of confidence but must overcome it to trust her instincts again (internal conflict). She may also feel conflicted about how she drinks to forget her troubled past, but at the same time, needs to forget about that in order to have a clear mind for the case (more internal conflict).

And of course, the best kinds of internal conflicts feed into external ones, and vice-versa: the longer it takes to catch the killer, the more confidence the protagonist loses, the less the town believes in her, the more she drinks, and so on.

Typically, the primary conflict is introduced within the first act and forms the foundation of the rising action from that point on. This is usually a combination of both external and internal conflict. (Say, a corrupt ruler kills the hero’s parents, and they must overcome their grief to defeat this villain and avenge their family.)

It tests the protagonists

Roadblocks are concrete crises or circumstances that prevent the hero from moving forward toward their objective. Often, the clock is ticking against them, and the less time they have to reach the finish line, the greater the stakes become.

For example, in a romance where the protagonist tries to impress her crush, she might have many escalating difficulties. First, she might trip and embarrass herself. Then, she might accidentally buy her romantic interest a cup of coffee with the wrong kind of milk, causing an allergic reaction. Finally, against all odds, they go on a date — only for the heroine to accidentally lock herself in the bathroom!

Of course, roadblocks should feed into the development of the story and main character(s). In our romance example, perhaps it’s only after embarrassing herself so many times that the heroine realizes she can’t let shame get the better of her, and that it’s only through embracing herself — blunders and all — that she’ll find enduring love.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

It introduces subplots and side characters

A story filled with nothing but tension would be pretty intense to read, right? Thankfully, most stories aren’t just one roadblock and/or personal conflict right after the other — they involve a balanced cycle of tension and release.

Each crisis might be bigger than the last, but there’s always that bit of respite in between periods: a little comic relief, a B-story, or a quiet moment between two characters. Even in an action-packed sword-and-sorcery fantasy novel, your hero wouldn’t be fighting dragons and rival knights every waking moment — he’d also take some time to recover at the local inn or to share a sweet romantic moment with the princess.

It builds suspense up to a boiling point

The boiling point is the final stage of the rising action — arriving just before the climax, at which point the story actually “boils over.”

To clarify, the boiling point is not the climax itself, but the final incident (or sequence of incidents) that triggers it. After this, the rising action (which was always “rising” to the climactic scene, after all!) is over, the climax occurs, and the falling action and denouement follow, putting a final bow on the story.

3 examples of rising action

Now, let’s dive into some useful examples. To show how rising action manifests in different genres, we’ll look at three extremely different stories: one mega-famous book from the literary canon, one contemporary heist comedy film, and one iconic theatrical tragedy.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The promise of the premise of Fitzgerald’s third novel is pretty well-known: a mysterious millionaire must overcome various physical and psychological hurdles to win back his first love.

Developing internal and external conflicts

There are various internal and external conflicts in the rising action. One external conflict involves Gatsby having to win over our narrator, Nick, in order to ask him for a favor. Once Nick reintroduces him to Daisy, Gatsby must then compete with Tom, Daisy’s husband, for her affection, which is another external conflict. An example of an internal conflict is Gatsby having to fight his own obsession with the past, which threatens to compromise the future he supposedly wants.

The primary conflict in The Great Gatsby can be summed up as the following combination of external and internal conflict: Gatsby is so fixated on the past that he struggles to actualize his goals for the future, namely to be happy with Daisy and content with what he’s achieved.

Testing the characters

The rising action includes a series of roadblocks. Having first overcome Nick’s dubious opinion of him in order to make contact with Daisy, Gatsby must then find a way to get Daisy alone and express his feelings. Then, as they embark on an affair, both struggle to keep it a secret — particularly from Daisy’s husband, who is wary of Gatsby’s strange behavior and Daisy’s agitation.

Gatsby’s key qualities are revealed as he deals with these challenges. We see him grow increasingly anxious as he realizes that maintaining an affair is no easy thing — especially because, no matter how lovely Daisy is, she cannot live up to his expectations.

Introducing subplots and side characters

Though readers (and certainly viewers of the Baz Luhrmann adaptation) will remember The Great Gatsby’s dramatic parties, car crashes, and fisticuffs, the book contains plenty of quieter subplots to keep the balance — Nick speaking with Jordan Baker, Gatsby taking Nick to lunch, and so on. These moments do not just serve the pacing; important background about Gatsby and Daisy is revealed during the seemingly innocuous posh lunches and gossip sessions.

Reaching a boiling point

In this story, the boiling point is almost literal — one sweltering afternoon in September, Nick, Gatsby, Daisy, and Tom adjourn to a hotel suite to cool down. Tom and Gatsby argue over Daisy, and Daisy stirs up further emotions by saying she loves them both. Though all parties are upset and not exactly stable, Daisy and Gatsby leave in his car, setting the climax (Daisy’s hit-and-run and Gatsby’s death at the hands of George Wilson) in motion.

Ocean’s Eight

Our second case study is Ocean’s Eight, starring Sandra Bullock and Cate Blanchett. This modern romp has a much more lighthearted premise, albeit still with high stakes: a savvy con artist and her partner-in-crime recruit a team of experts to steal from the star-studded Met Gala, which will net them millions apiece — if they don’t get caught.

Developing internal and external conflicts

An external conflict in Ocean’s Eight is that Debbie Ocean must outsmart her fellow Met Gala attendees, security, the police, and a host of other people in order to pull off her heist. There is also an internal conflict: Debbie is caught between the desire for heist-related revenge on her scheming ex and the desire to move on in a healthy manner.

As with The Great Gatsby, the primary conflict is a combination of both types of conflict. The diamond necklace that Debbie intends to steal is ridiculously well-guarded. Luckily, she has a few tricks up her sleeve — but she’s also distracted by a swirl of internal conflict triggered by her ex, who’s also attending the gala.

Testing the protagonist

Debbie's first roadblock is simply getting everyone on board with the heist. Then there are various challenges related to the plan itself — creating a replica of the necklace and the magnet needed to unclasp it, hacking the Met security system to create a blind spot on the cameras, getting the necklace off the wearer’s neck without her noticing, and so on. Debbie stays cool and collected as she tackles each problem, her own confidence instilling the same in her team.

Introducing subplots and side characters

Even as the pressure mounts perilously, we get many clever moments of comic relief throughout Ocean’s Eight. For example, Debbie and her partner Lou blow soap bubbles as a diversion, street hustler Constance negotiates her terms at Subway, hacker Nine Ball brings in her little sister to help with the heist, and celebrity Daphne Kluger acts deliciously, indulgently melodramatic at every turn. Each comic scene adds subtly to our understanding of the characters: Debbie and Lou are creatively strategic, Constance is really just a scrappy kid, etc.

Reaching a boiling point

With everything leading up to the necklace being stolen, the boiling point is when Debbie and her team escape the Met Gala with the necklace and reconvene, only to realize that everything is not quite as it seems — how did they get away with everything so cleanly? And where did their extra money come from? (Cue dramatic story reveal as Debbie tells everyone of her secret plans!)

You'll find additional examples of rising action in pretty much every single story you come across. A good exercise, if you're learning how to write rising action, is to write down each event in the stage as you see it — which we'll break down wiht our final example.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

For instance, for the event breakdown in Hamlet, you might write:

- The ghost of Hamlet's father appears: It tells Hamlet who murdered him and asks Hamlet to take revenge, which kicks off the main conflict.

- Hamlet feigns madness: Hamlet pretends to be insane while gathering information in dangerous territories.

- Hamlet stages the Mousetrap Play: Hamlet stages a play within the play, reenacting his father's murder to see his primary suspect's reaction.

- Hamlet kills Polonius: Hamlet accidentally kills Polonius while he's spying on him, which escalates the main conflict with Claudius.

4 tips to write rising action

Now that we’ve seen it in action, it’s time to talk about how to write something that could rival a novel like The Great Gatsby or a movie like Ocean’s Eight. Here are our top tips to keep in mind for tackling what is usually the longest (and therefore, arguably most important) element of plot:

1. Research the conventions of your genre

Before you write your rising action, it’s worth familiarizing yourself with your reader’s expectations of your genre so that you can deliver on “the promise of the premise.” (If you find that you’re naturally straying from the conventions of your chosen genre, it might be time to pick a different genre!)

2. Create engaging characters

The rising action is the part of the story where you will either lock in your reader’s interest or lose it. That’s why it’s important to take the time to develop engaging characters by exploring their wants, needs, strengths, and weaknesses. It’s also important to have a believable character arc, whereby the events of the rising action change your protagonist in some way.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Katniss’ fierce protectiveness over her family, resourcefulness, and difficulties trusting others make her a compelling protagonist. When she faces life-threatening situations, the reader becomes deeply invested in her fate, especially when she starts to overcome her weaknesses and put her trust in others. By creating characters with relatable motivations and vulnerabilities, you make the reader eager to follow their journey through the rising action and beyond.

3. Raise the stakes

While the inciting incident establishes the stakes, the rising action should up these stakes to keep on increasing the tension. You can do this by introducing roadblocks and secondary conflicts, which will raise the stakes by making the protagonist’s goal seem less and less obtainable. For example, in The Lightning Thief by Rick Riordan, Percy Jackson’s quest to retrieve Zeus’s stolen lightning bolt becomes harder and harder as he encounters a number of monsters and uncovers a conspiracy against him.

4. Allow some respites

However, you don’t want to go overboard with your roadblocks. A mistake some writers make is piling obstacle after obstacle into the rising action without any breaks. This much tension can become overwhelming for the reader, and too many failures can get frustrating. It’s important to allow the characters to have minor victories and respites to relieve some of the tension and give the reader a chance to regain their breath before the next action scene.

Conversely, the story shouldn’t have too many respites, as the slow pace will send your audience to sleep. A well-paced rising action needs the right balance of big, dramatic moments of tension and “smaller” moments of relief.

Hopefully, this guide has left you feeling confident about how to write rising action. It may be the longest element of plot, but it wouldn’t be a story on its own. Next up is our guide to writing a dramatic climax. Or, for more insights and tips on the earlier parts of a story, check out our full guide to the elements of plot.