Sign up for Tom's course to watch his prep week for free. These five lessons will cover the topics from this webinar in greater detail.

Well, hello everybody. Thank you very much for joining me this evening. It's lovely to have you all and I appreciate it's very early for some of you, perhaps in Australia and loads of different places. I will hopefully make this worth your while spending the next hour or so here.

What this session is about is talking about preparing to write a novel and the main keys for novel writing success. So whether you're thinking about doing NaNoWriMo, thinking about joining the writing course, or whether you're thinking about writing a novel more generally — wherever you're at in the writing process, or journey, this should give you some advice and tips in terms of how to start and think about planning before you begin to write.

So we're going to talk about the five keys to success. And what I think are the five key elements to think about before you start getting down to write. I'm going to talk about what I call the Five Ps. Which are:

- The Pitch

- The Protagonist,

- The Plot

- The Point of View

- The Place.

These are the five elements to think about, and do your prepping and planning for, before you get there to novel properly. Once I've done the presentation, we'll have plenty of time to ask questions on any of these topics.

About me

I have worked in publishing for almost 25 years. Yes, quite a long time now. I started work originally as a bookseller. I always think that if you're interested in working in publishing and even writing as well, a job as a bookseller is one of the most useful and practical things you can do. From that I got a job as a copywriter — so I was the guy who wrote all the blurbs on the back of the book. So that was my kind of starting job in publishing.

From there I went on to become a commissioning editor, an editorial director and publisher at different kinds of publishing houses. And in total I've commissioned and edited over a hundred titles. A whole range including bestsellers, prize winners, fiction, and nonfiction.

At the same time as doing the editing, I've also worked as an author. So I've written, and co-written a dozen books of my own — both fiction and nonfiction. And over the last ten years or so, I've also worked more as a ghostwriter. I've written around 15 books, and again these include kind of prize winners and international top 10 bestsellers. Mainly memoir, that tends to be what I work in and over a whole range of subjects with a whole range of celebrities. I've signed enough Non Disclosure Claims — I can't tell you any of the people who I've worked with — but it's a really interesting job and I've worked with fascinating individuals over my time.

The other string to my bow is I teach novel writing. I've done this for about a decade. And last year I joined Reedsy as Head of Learning. The main thrust of that in the beginning is to launch our How to Write a Novel course, which began in September. And I'll talk a little bit about that towards the end of the presentation as well. So that is me, but let's move on.

I wanted to show you this slide quickly — which is an example of some of my previous students who've gone on to publish. I've had about 30 or 40 [students], to have gone onto publishing deals.

So Joanna Cannon, on the left, was a huge literary bestseller here in the UK. Deborah Masson won the Bloody Scotland crime debut novel of the year. It's a kind of dark crime series she's writing set in the middle of Scotland. Asia Mackay, who is a comedy writer. This was a book about a new mother who had a secret life as a spy and that was the runner up in the Comedy Women in Print Awards. And then most recently this year, Alice Chow, A. Y. Chow, whose debut novel, Shanghai Immortal, was a number one Sunday Times bestseller here in the UK, and has just been published in the US as well.

And all those people were exactly like you are now. When they started their journeys, they had hopes and dreams and ambitions and an idea for a book... and it worked. It's always quite instructive and quite inspiring to know that those people are there and it does happen. I've seen these people go from the first sentence through to the bestseller list. So it can, and it does, happen. So have that faith and belief that it could happen to you.

The 5 P’s of Preparation

But in order to write your book, before you start you need to think about preparation. And what I'm going to do is focus in on this evening is what I call the five Ps of Preparation (a nice little bit of alliteration here), and these five Ps are as follows.

- The Pitch

- The Protagonist,

- The Plot

- The Point of View

- The Place.

So I'm going to talk through each of these in turn, and if you've got any questions at the end we can go through and discuss. I'm going to begin by talking about the pitch.

The Pitch

It's sometimes called the elevator pitch — I think that's where the term came from originally. It was an American business book in the early 1970s, and the idea was that if you are in a lift with a potential buyer for your product that you've got your pitch there ready to show and sell. So that's where the idea of a pitch comes from.

In terms of a novel, it is more about coming up with a short single sentence summary of what your book is about.

As you might guess from its origins, it is important later on in the writing process as a selling tool. So whether it's the line that you put in your covering letter when you're writing to an agent or a publisher. It might be the line that you use on your Amazon blurb. It might be the line on the back of the book where you're trying to get someone to buy the book. It's useful to have the pitch there. I think it's a really important element to have for the writing process.

You might be thinking, why should you be thinking about a sales line here at the start? And I think, “don't think” about it. Don't think of it as a sale. At this point it's thinking about helping the writing process. I always think that the sharper and clearer you can make that pitch, the smoother a writing journey you'll have.

I've certainly seen books from the sales point of view where it's got a clear selling point and it works in terms of going to the bookshop. In terms of going to booksellers and going to the readers. But in terms of the writing as well, if you can clarify in a single sentence what your book is about. That will stand you in such good stead for the writing.

One of the reasons for that is because it really forces you to think about what the book is about at its heart. Because if you've got 100 words to describe your book, or 200 words to describe your book, you've got plenty of space and you can waffle away and add in this, that, and the other.

If you've got a single sentence, you've got to decide and make a decision.

Okay, this is the most important thing in the book.

It really helps firstly to focus your mind. But secondly, when you are writing and you get stuck — or you think I'm not sure where this is going — you can use it as an aide-memoire to go back to thinking about, “Is this particular chapter linking up to what the book is about?”

So the more that you can come up with that pitch, the more that you can think about it, then you can have this line to work with. And every time you're unsure, or unstuck over what it is you're working on, you'll be able to refer back to this to remind you.

I always say to my students, if you've got that on a post it note, and you can look up to it and think, Okay, how does this chapter add to this central point of the story? And if it's not adding, then maybe the book is going off in the wrong direction, that little particular point.

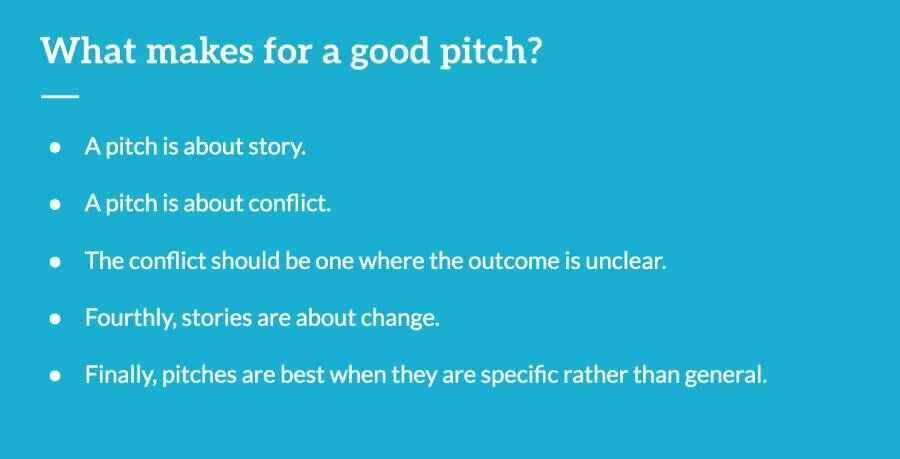

So what makes for a good pitch? It's a number of things. Firstly, a pitch for me is about story. It's not about what the theme of the book is – as interesting as that might be. It's not about how you're telling it. You might have multiple points of views and flashbacks and this, that and the other.

It's about the story and focusing on what is driving the plot.

What tends to drive the plot for me is conflict. You need conflict there at the heart of what it is you're writing to get that dramatic tension into the story. And that conflict, I think, is one that should be one where the outcome is unclear. I think that is really, really important.

If there's a conflict, but it's fairly obvious how it's going to end up, then the dramatic tension is lessened.

So you want a conflict at the heart of your story, of your novel, but one where it's uncertain how that's going to play out at the end.

I'm going to talk about this again in a moment, but, stories are about change. That is a crucial element of writing, whether it's plot, or whether it's character. If you can get that element of change into the pitch, so much the better.

Finally, I always think pitches are best when they are specific rather than general.

If you can get those little details in there, whether it's character names or setting, those specifics make your story more individual and unique. And it's not an easy thing to do writing this pitch if you've got 20 25 words maximum. That's hard.

It might actually be one of the hardest sentences that you write in the whole process of writing the book, but it's the one that probably will be the most beneficial and the most useful if you get it right.

I want to give you one very quick example about the difference between a pitch – which I think is quite general and doesn't have conflict – and one where it works.

The example I'm going to give you is a classic romance pitch — it's a story of boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love, get married, and live happily ever after.

Now this is a story. There is a narrative there, there's a progression, there is a beginning, a middle and an end…

But hopefully you can see there's no conflict or any tension in that story. It's all too smooth and too easy. So here are a couple reworkings of that, that I think make the same story more interesting.

Boy meets girl. Boy and girl go their different ways. Boy and girl meet up years later, now with different people, but still with feelings for each other.

Now this immediately to me feels like a more interesting story. And in terms of what I was saying about that question of outcome and conflict, it's less clear are they going to stay with the people they're with now, or are those feelings going to take over and they're going to get back to the person who they fell in love with in the first place.

To give you one more example: boy meets girl. Boy's family wants him to marry a different girl and will disown him if he doesn't.

So here you've got conflict. You've got choice. There's going to be consequences in terms of what his decision is. Is he going to choose his family, or is he going to choose the love of his life?

That, is tension there. That's a conflict at the heart of the story. Hopefully you can see that both those examples at the bottom are better, stronger, pictures. There's something intriguing in there, and you as a reader, you're thinking... I'm not sure how this is going to play out, but I want to read on and find out what that conclusion is.

The Protagonist

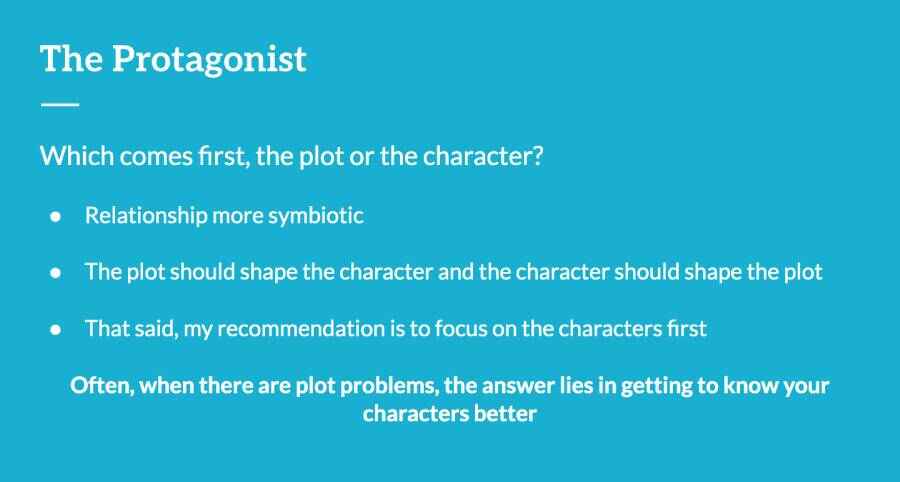

Sometimes students ask me which is more important; which comes first, the plot or the character?

This is a slightly false question because in a good novel the relationship is slightly different. Rather than one being more important than the other — in fact, they're symbiotic. Their roles are interlinked with each other.

In a good novel, the protagonist should shape the plot, and the plot should shape the protagonist. It should be this two way process where each of them are having this effect on the other. But, if I had to choose out of the two, my usual recommendation is to focus on the characters first.

There's lots of books out there on how to write plots and people get stuck into thinking about the plots and sometimes the characters get forgotten. And actually the character is more influential — perhaps is one way of saying it — of the two elements.

I often find with students that when people get stuck with the story, or they're not sure where it's going, the answer to plot problems nine times out of ten, in my experience, isn't to do with adding in more plot or challenges of the plot.

The answer lies in getting to know the characters better.

So usually if you've got a plot problem, it means you don't know your characters well enough. If you can go back through and get to know your characters in a bit more detail, then more often than not, that will answer your plot problems.

The most important element, is this question of character motivation. And the key detail to know about your characters, and about your protagonist in particular, is their wants and their needs. And you might be here thinking, what's the difference between the wants and the needs? It’s that one's slightly deeper than the other.

So a want, or what the character thinks they want, should really drive the first half of the narrative. And then that character’s need is something deeper, more fundamental. And that should shape the second half.

When you've got those elements there that underpin who that character is, and as a result, underpins the narrative as well, there is a relationship between the two. And when I go on to talk about plot in a second you'll be able to kind of see that a little bit more.

I'm going to give you a couple of examples of wants and needs, because sometimes it's fine for me to say this, but what does it actually mean in practice?

The first one, a character might want to be famous…

That might be their initial goal driving them in the first half. But what they really need is to be heard. So it's a false goal they're in for to start. And then they understand what it is that more fundamentally they need.

Second example, protagonist might want to get married…

But what they really need is love. Not necessarily the same thing. I'm not going to comment on relationships, but yeah, it can be different things.

Then the third one here, a character might want to see the world…

But what they really need is a home. And hopefully you can see with each of those examples, and the way I'm talking, is that in the widest, most fundamental sense, you're beginning to see a story and a story arc there.

I'll talk about that again in a second when we get on to plot. And as I say here, if you've got the wants and needs clear in your mind, then that creates a structure that is character embedded — and a feasible story to follow. Those, for me, are the other narratives and novels that are the strongest when that occurs.

The Plot

So let's move on to the third P, which is the plot. When you're planning the book, one of the questions is, “how much plotting to do in advance?”.

You may well have heard this debate amongst writers between planners and pantsers, — between writers who plan before they start writing, and planners who will write by the seat of their pants. They don't want to plan in advance, they want it to be a surprise, and a journey, and an experience, as they write.

In reality, rather than it being an either or thing, it's a kind of sliding scale and every writer is different. So one of the keys for you as a writer is to work out how much planning you need in order to be comfortable to start to write.

I've got a couple of quotes here from different writers to give you a sense of this kind of spectrum of planning.

"I have the feeling that if I knew what was goingto happen in a story I wouldn't need to write the story... I've never regretted not plotting'

- Ian Rankin

"It takes me about three years to write a novel and I spend roughly two years figuring it out and one year writing it."

- William Boyd

Most writers end up somewhere in the middle between these kind of two extremes. So Patricia Highsmith, a classic crime writer who I love in one book said:

“A a plot should never be a rigid thing in the reader's mind when he starts to work... I like surprises myself. If I know everything that's going to happen, it is not so much fun writing it.”

And in her book, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction she talks about plotting up to a certain point, so say the first 120 pages or something. And then keeping it open after that. So she does a bit of plotting and planning, but then lets it kind of flow out from there.

There's no right and wrong in how much plotting to do. It's working out what will drive you. Will you feel more comfortable writing if you've got that planning and preparation done in the background? Or will you feel more energized if you've got that freedom to explore and see where it goes?

So find your place on the spectrum and don't tell, or don't listen to people who say you must do like this, or you must do like that.

These are some of the many how to plot books.

- Joseph Campbell - A Hero with a Thousand Faces

- Christopher Vogerl - The Writer’s Journey

- Christopher Booker -The Seven Basic Plots

- Jessica Brody - Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

Probably the starting point is Joseph Campbell's book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which was famously used by George Lucas, when he wrote Star Wars. Which, delved into a lot of myths and legends and came up with these different archetypes.

Christopher Vogel is a writer's journey you may have heard of. Christopher Booker's The Seven Basic Plots divides all stories down into seven different main plots. And then more recently books like Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, is there as well. There's lots out here to read and explore.

Personally, I'm always slightly kind of wary of using these. There’s a another book on storytelling by Will Storr called The Science of Storytelling, which I really like. And he always says that these recipes work — but the problem with recipes is that every time you follow one, you get the same bloody cake.

Certainly over the years having taught novel writing, I've seen so many books where I can see the drawings of the writer's journey. And I can see where they followed that formula or that structure. And so for me, and certainly on the novel course when I teach, I'm less interested in those models and structures.

What's more useful are two things. Firstly, to go back to the books that you love and have a think about why those work. That's the first thing to say.

Secondly, think about plotting principles. For me that is the starting point. And if you can get those principles right, then you can flesh out the novel in a fresher, more individual and distinct way.

The 3 C’s

So we have the five Ps, now we've got the three Cs. And the three Cs when you're plotting for me are:

- Change

- Causality

- Complications

The first one is Change. I mentioned this earlier, Will Storr again in his book says a more creatively freeing way of looking at plot is as a symphony of change. And this idea, I suppose not on the biggest level, that when you're writing a novel your protagonist should be a different person at the end of the book to who they are at the beginning. That should be the starting point.

But that idea of change is embedded throughout the story. It's not just changing character, it's changing circumstance and situation in terms of plot. It's on a bigger picture level, it's on a small, on a smaller level as well.

And two of the things that we talk about in detail on the course, which are crucial, are these ideas of change and movement. The more you can get those embedded into the story, the stronger the novel and the narrative would be.

The second of my three C's is Causality. This is all about creating links. And I've got a quote here from Ian Forster's book, Aspects of the Novel, which I always think is the best description. I've come across on this and he says:

“A plot is a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot. The time sequence is preserved. The sense of causality overshadows it.”

And where plots work best is where you've got this sequence of events that happen in one causally linked chain. They can only happen in one particular sequence, and when those are in place then the plot is tight.

If you can look at your plot, and you can move things around, then that narrative isn't kind of tight and taut enough. So thinking about the element of causality is crucial.

And then the third element after change and causality is Complications. So going back to Patricia Highsmith again she says:

“The improvement of thickening of a plot is the piling on of complications for the hero, or perhaps for his enemies... If the writer can thicken the plot and surprise the reader, the plot is logically improved.”

That's really, really important. To make your character grow and change, you have to make life difficult for them. So the more complications and more things you can throw in their way, the more they are forced to think about who they are. The more choices they have to make, the more difficult choices with consequences they have to make, and as a result they change as individuals. Those three elements are crucial.

With what I was talking before about character, my recommendation, is to start with character change. So thinking that your protagonist should be a different person at the end of the novel, to who they are at the beginning. And this comes through with wants and needs. You can use these character motivations as an overarching framework for your narrative and it sort of plays out like this.

- Protagonist wants x

- Protagonist searches for x

- Protagonists realises x isn’t enough. Learns that what they really need is y

- Protagonist attempts to achieve y

- Protagonist achieves y.

It's quite a simple structure that, but it gives you a sort of umbrella framework, whether you're a planner or a panser, it gives you that overall shape, that direction of travel as to where you think that the book is going or should be going. So if you've got that in there it’s very effective.

If you're a planner, you may want to then flesh that framework out. I would say this is about plotting out a chapter by chapter plan under this framework. Depending on how much detail you want to go into, you can either have that umbrella and leave it at that; or you can go down to a more granular level and have the points there, kind of plot by plot.

If you're doing that, I would stress test with the Enforced Society of Causality and check that those links in the chain are strong. And if it feels lacking at any point, add in these complications that I was talking about.

But as I was saying earlier, make life hard for your protagonists. They can put their feet up at the end of the book. By making them make choices, and difficult choices — choices with consequences — it forces them to choose and it forces them to change.

If you think back to that pitch I was saying earlier about the boy whose family were saying you've got to choose between marrying this person or being disowned. That is a difficult choice, and a choice with consequences. That's what good fiction, at its heart, is about.

So there's lots of books out there about plot. But for me, thinking about those first principles with plotting, this is the way to start. And in particular, think about how those are related to the protagonist. If you get the plot and the protagonist pulling together, that's when the novels are their strongest for me.

The Point of View

So the fourth P is Point of View. And this is an important thing to think about from a practical point of view. I'm talking here about the point of view, and also the tense that you tell your story from. The reason this is important, is that it's such a big job to change.

I speak from experience myself. If you start writing a novel in the first person, and then 15-20 thousand words in, you realize that's wrong when it's in third person. It is an absolutely horrible job going back to unpick. It's thankless, it's time consuming, and I wouldn't wish it on anyone. So if you can make that decision before you start and stick to you're going to save yourself a lot of time and grief later on. It's true with point of view, it's also true with tense as well.

So both of these are choices to think about at the start. It's worth saying with both these choices that there's no right or wrong in what you choose. All these options, the ones I'm going to kind of lay out in a second, have positives and negatives. The two questions I always say to think about when you’re thinking about plot, thinking about the point of view, and thinking about the tense are these two questions.

“What is the best viewpoint and tense for the particular story I want to tell?” — Some viewpoints and some tenses will be more suited than others.

“What is the viewpoint and tense that I, as a writer, feel most comfortable writing in?”

For me, as a writer, I tend to prefer writing in first person. I know that's my kind of natural viewpoint I will write in. So I would have to think quite carefully if I was writing a book in third person, because it would be a more difficult thing for me to do.

One of the things you can do at the start, is to write out a sample scene. Write it in different tenses and different points of views and see which feels the best fit for you and for your story.

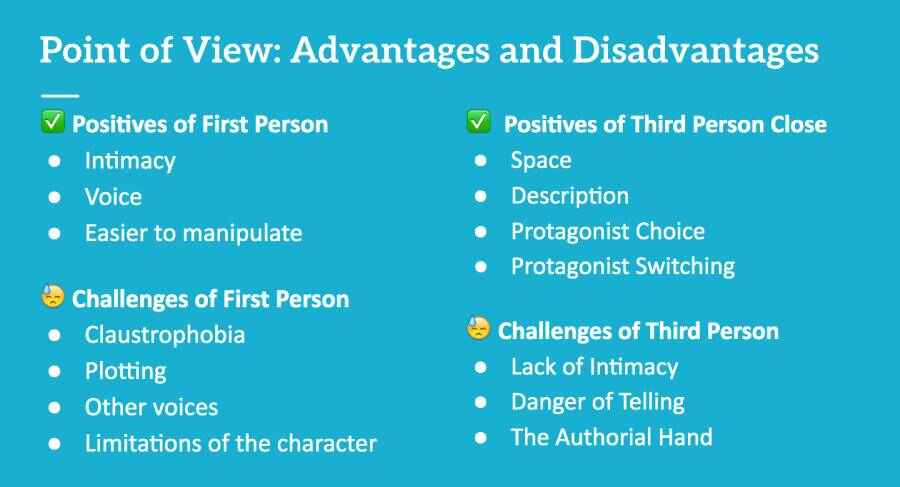

With points of view, I'm going to focus in on the two that most novels are written in; which is first person and what we call third person close.

Third person close is when you are, I was described as, like Long John Silver's parrot. You're with the viewpoint of one particular character. You can see into their thoughts rather than being a more omniscient viewpoint where you can see everybody's thoughts.

In terms of first-person, these are the advantages. As a way of telling it's more intimate. It's easier to get inside that character's voice. And that's the second point — you can bring out the voice of that character and the voice of the book more easily.

Sometimes you will find that different agents and publishers talk about the importance of voice, and first person is definitely a helpful way of getting that in the writing. First person is also easier to manipulate the reader if you're that kind of writer who wants to have an unreliable narrator. You're with this character all the time, so it's easier to kind of steer the writer — steer the reader — in a certain direction.

The disadvantages, or the challenges of first person, is as a viewpoint it can feel a little bit claustrophobic. You're stuck with this character throughout, and that can be a bit confining. If the reader doesn't like that character, are they going to carry on if they're going to stick with them for the next 200, 300 pages?

It creates challenges sometimes with plotting. You have to find a way to get this character into every scene, even if they're not naturally kind of coming into that moment. It can be more difficult to get other voices into the writing. And there can be limitations with the character as well.

So, for example, if you're writing from the point of view of a child, that might be difficult in bringing in bigger, deeper themes in the novel. Or if your character is, I don't know, a football hooligan, then it might be harder to write the nice bits of description. Because that character wouldn't be thinking in that way about how places look, or I might be being unfair to football hooligans there, but you probably get the point.

In terms of third-person close, the switch is sort of the opposite really. So the positives are you've got that little bit more space in the telling. As opposed to the first person, and that certainly helps with things like description. You've got more choice to the protagonist. It's easy to switch between scenes and character, that can be useful in terms of plotting.

The challenges of third person, again the opposite of first person. So it's a lack of intimacy. It's a slightly more distanced telling if you're not careful. And there's a danger of using the third person to be more old-fashioned telling of the story. This slightly scary, kind of, authorial hand —mystery narrator — saying little did they know…

In terms of tense, if you're writing in present tense the advantage is immediacy. It's a very good tense when you're trying to capture experience and the moment. It's effective and it's very popular in particular genres.

So for example, a lot of young adult books, a lot of psychological thrillers, which are about experience written in this tense. And sometimes it can help to kind of bring the past closer.

Hilary Mantel, for example, who wrote Wolf Hall, would use the present tense sometimes to write her historical fiction as a way of bringing the past kind closer to the reader.

The downside to present tense, by comparison, can feel a little bit claustrophobic. Can feel a little bit flat. It's less useful and helpful when you're telling a story over time. So that advantage you get with the immediacy and the here and now, if your story is being told over three or four years for example, with flashbacks, then that's harder to do with present tense.

And in the same way with first person, third person we've got a flip here, when we go on to the positives of the past tense this sometimes feels more natural. It's a more kind of traditional way of telling a story, so you're all immediately into a tradition. It gives you a bit more depth into the telling. And as I say, it's a more useful way to tell a story over time.

The challenges here are in terms of creating distance. Pace can be a challenge sometimes. Sometimes writing in the past tense can feel a little bit slower. And again, there is that temptation to be authorial.

If you've got these four options, then you've got first person present, third, first person past, third person close present, and third person close past — and it's a sort of sliding scale. The first person present is the most intimate and immediate, and the third person close past is the most distance with most space.

Experiment with these and work out what works for you, because if you have to change your mind further down the line, it's a lot of work to unpick.

The Place

There's a couple of questions to ask yourself; firstly, most naturally, where is your book going to be set? It sounds fundamental, but if you know that before you start writing, it really helps.

And it helps firstly in terms of character. Quite often there's a link between, who a person is and where they come from. So I think that that is useful to have in there. Think too, if it's, if it's a real place, how you're going to research it.

So David Nichols, a wonderful writer, wrote a piece where he talked about his first books, he spent the time to go and visit the places, and then in later books he then used internet research for locations. So if the places are real, think about are you going to go and see them? And do that prep before you start writing.

The second question, which people often overlook, is when your book is going to be set. Is it going to be in the here and now? Is it going to be in the past or the future? Or in the near past or the near future? All of those elements make a difference.

To give you a couple of recent examples; do you want a world where you've had lockdown and coronavirus? I know some writers who have either sort of set novels kind of five years before, or kind of five years later, they didn't want that in the mix.

It's a question of technology too. It's a lot more difficult these days. Sometimes with plots, if people have got mobile phones or access to the internet, can they be lost or trapped? If that's the kind of book you're writing, in quite the same way.

And then depending on the when, if it's set in the past, you're going to need to do research. If it's going to be set in the future, then you're going to need to use your imagination a little bit more.

A couple more questions very quickly on place:

Firstly, is your story world going to be real, fictional, or a mixture? - To give you an example of each, The Day of the Jackal by Frederick Forsyth. A classic thriller about the attempted assassination of the French President, Charles de Gaulle at the time, was very much set in Paris and it worked because it was authentic and real and used real places very effectively.

I was born in Salisbury, which is in the heart of Thomas Hardy's Wessex. And Wessex was a place where Thomas Hardy sort of transposed it onto real places, but it was a sort of fictional world, so it was sort of a composite of the two.

And sometimes you will have writers who create fictional places inside real places. So there's another we look at in the course called In our Mad and Furious City by Guy Gunaratne, which is set on a housing state in north northwest London. So the housing state is fictional itself, but the London that surrounds it is real.

So have a think about, Do you want to have that authenticity of real places, or do you want to have a bit more space and freedom to have somewhere kind of fictional?

And then the last question in terms of place is How much detail do you need to know before you start? So think about world building, if you're writing a science fiction or fantasy book, you may need to do a bit more planning and prepping than if you were setting your novel in contemporary London.

Think about what sort of writer you are.

I know when I write first drafts they tend to be quite dialogue heavy, then I put my description in in the second draft. I know I don't need to do too much thinking and planning in terms of place to begin with. And that goes back to that idea planning versus pantsing — are you the kind of writer who will feel more comfortable with this detail or are you happy to go with it and add that information in a little bit later on?

To sum up then, these are the Five P's I recommend thinking about before you start writing.

- Pitch

- Protagonist

- Plot

- Point of View

- Place

Think about the protagonist and think about the plot. What kind of writer are you? How much planning you want to do? Help yourself by thinking about the point of view and tense before you start writing. And finally, have a little think about place as well. If you've got all those elements in there, then you'll be in a really good place to start writing.

How to Write a Novel

I've been teaching since we had our main start in September, and this is a 101 day course over 15 themed weeks.

So the idea is that we want you to write a full manuscript and come out with a full draft from start to finish. We have recorded a lot of videos. There's 20 to 25 hours of videos in total. So you get a different video lesson Monday to Friday. And that's accompanied by a full lesson for a deep dive into each topic.

We have an author’s panel. Nine fantastic authors for different genres who talk about different writing topics each weekend. And we ask, or the recommendation is, you’re trying to write 5, 000 words a week. And if you do that, then over the duration of the course, you should get a full manuscript down.

As you can see on the start dates, we've got one towards the end of this month, which is time to begin with NaNoWriMo. And then a kind of new course on January the 8th. And these are the themes that we do; you can see there's a, there's a different kind of writing theme kind of each week that we, that we focus on.

The other elements of the course, I think are really important to mention, is that we have a series of master classes. So I teach a master class each Monday. And these are a mixture of either a kind of deep dive into different topics or live editing, or we have kind of guest authors. You get a writing community that you join as well. We have Feedback Friday where you can share and give feedback to each other.

So it's a — I'm really excited about the course. It's a great one to if you're interested in writing, getting stuck in and as I say, you know, get that prep in first, and if you do that then you'll be in a great place to begin writing.