Visit Michelle's ghostwriting profile on Reedsy

I am so excited to be here today to talk to you about maybe my favorite topic ever, which is how to start writing a book. I'm going to start by explaining exactly why this is my favorite topic to talk about.

About me

I started writing my very first novel in 2007 — I never finished the draft, but I started. I didn't get an agent until 2010, and that book didn't sell, but I did get an agent. And then, in 2014, my first novel was published by Penguin.

Now, in 2021, I have 16 published novels and I've done a lot more as a ghostwriter and I also do some book coaching. And in the last three years, as I've really built this ghostwriting and book coaching career, while I've continued to publish my own novels, ghostwriting and book coaching really are what make the bulk of my income at this point.

What I do in both is to help other writers avoid spending seven years from getting their idea for a book and actually finishing it and publishing it, because that was the spread for me.

Honestly, these two jobs, ghostwriting and book coaching, have a really similar process, more so than you would think when it comes to actually getting started on writing a book.

Getting a book on its feet

In both cases, what I do is start by talking to my client about their idea and read literally anything and everything they have written about this. So they will send me documents which are just brainstorming and everything's kind of a mess and out of order; they'll send me character sheets; they'll send me maps that they've drawn. I've had them send me illustrations, which are usually pretty amazing. And I've read scripts and screenplays that some clients want to turn into a novel. Just everything you can imagine.

I read all that and I take notes and then we talk, we do consultations and I help them find the story in that idea. I mean, the character’s arc and the journey they go on and the conflict and the stakes. And then in both cases, we outline it together and I guide them through the process of finding the structure.

This is where the two jobs diverge. If I'm the ghostwriter, I write the book, and if I'm the coach, they write the book and I just give them feedback along the way.

So what I've learned doing this is that we all start out with so many of the same issues when we have an idea for a book. When I think back to 2007, when I was writing my first book, it took me years to figure out on my own the tools and the strategies that I now use to help my clients turn their ideas into books way faster. And that's really what I want to share with you guys today. So we're going to talk about three things - sifting through all of your ideas, which I know is overwhelming, and then finding a plot in your premise, and then finally, I want to give you guys some practical tips for actually starting to write.

Step 1. Sifting through the ideas

So first up, we're going to talk about sifting through the ideas. I couldn't tell you about the first time I got an idea for a novel because the truth is, I think I got like 50 book ideas all at once, or maybe it was 50 different concepts for 50 different novels. It was like the moment I really decided writing a novel was something I was going to do, my brain would not stop throwing ideas at me. And I didn't know if they were all for different books or is this all for the same book or what? And it was so overwhelming. And while I was really excited, the overwhelming feeling meant I couldn't just sit down and write because I had no idea where to start. I didn't even know which idea to pick.

And this is usually consultation number one with my clients - talking about all of these ideas and figuring out: where is the story in all of this? So at this stage, I suggest you do one of two things.

1. Talk about your ideas

Talk to someone, preferably a writer but it doesn't have to be, about your idea. This is what book coaches are for, but you don't have to spend the money - I didn't when I was starting out, you just need a critique partner or a good friend who's willing to listen. I am very fortunate and I have now a great friend who is not only an author herself, but she also used to be a literary agent and we used to have a standing date to meet up once a week and talk to each other about our books and what we were working on. And now, obviously we can't do that anymore but we pick up the phone to talk out our ideas and it just never fails to help me get past any blocks I'm feeling and to have big revelations about myself.

2. Free write your ideas

Now, you may not have anyone to talk to, or you might prefer to keep your idea private, and I respect that. I had a comment on one of my recent YouTube videos where someone said, ‘If I tell anyone about my idea, the muse walks out.’ I understand that's how it works for some people. So maybe this isn't an option for you. If that's the case, start a brainstorming document to just free write about your idea. Something I used to do with some of my younger students but which I think could work for all of us is to turn the font white in your document. That way you're not rereading through what you wrote as you write it. You're not judging yourself. You're not thinking, ‘oh, that sounds ludicrous.’ Just turn it white so that you can't see it and let yourself type and see what comes out when you're all done. Once you have all of these ideas, highlight it, turn the font black and see it. You’ll probably be amazed at how much good stuff is in it.

What’s the starting point of an idea?

So as far as how an idea starts, your starting point could be anything. It might be a pitch like Ocean's 11 meets Mistborn. It might be a character, you might just want to write about a school teacher with a secret past, and maybe you don't even know what the secret is, but you want to explore that. You might start with a premise like ‘I want to write a haunted house book.’ Whatever that seed was for you, start with that. Just write that down and start asking yourself questions and just let your mind wander on it.

Once you've got the idea really talked or written out and you're excited about it, the next stage is fear. You get to a point where you can envision the story. You can imagine how potentially great this novel might be, and you're afraid you won't be able to let it happen. And if you don’t fail, if you don't know. So you just don't start. I have been here so many times and I think if you follow me on YouTube, you probably know what is coming next.

Chipping away at marble

I used this in a recent video on my channel. I've used it a few times, but I'm going to use it again because I just really love this analogy. So one of my favorite videos on YouTube is called ‘The Making of a Marble Statue.’ I'm no artist, I'm definitely not a sculptor, and when I see a statue or a sculpture in a museum I can't fathom how the artist accomplished it. And I think this is much the same way. A lot of us writers look at a published novel, we hold it in our hands and we're like, ‘how do I get to this? How do I take a hunk of marble and turn it into something that is so beautiful and so detailed and so real.’

Pick away at your idea

It starts with a hammer and a pick. The first stage is that the sculptor roughs out the block with a hammer and pick, and it's a big pick and a big hammer. This is a big, messy process. And what you see — the hunk of marble — doesn't look anything like the finished sculpture. This is you finding the shape of your story. At first, it's not going to resemble what's in your head at all. You're imagining this beautiful woman in her robe lounging, and you've just got this jaggedy, raggedy-looking piece of marble. It doesn't look like a woman. This is the point where most people starting to write their first novel give up because it doesn't look like the way it looks in their mind.

Don't give up at this stage, you are just finding the very general shape of the final verdict, the final product in the marble. You're making a huge mess. That’s the writing process. Especially in the beginning, you are making a mess and that's how it's supposed to be.

Now you can go about this in a lot of different ways. A lot of it depends on how this idea came to you in the first place. If you had an idea for a character, like with a persona, a specific personality type, or someone with a certain ability, maybe you just want to throw them into a scenario and see what they do. Or maybe you came up with a magic system or a fantasy world, and you want to explore it, but you don't know who the character is yet, so just try worldbuilding for a little bit. Or maybe you've just asked a really good ‘what if’ question and you want to try to answer it and you're not sure what that's going to look like.

These are all really great starting points and really common ways to get ideas for books and at this hammer-and-pick stage, you want to spend some time with your big hammer and your big pig hacking away until you can start to see your main character or characters, and just kind of generally who they are and how they might change from the beginning to the end of your book. You want to take a hammer and pick to your setting and just get an idea. And this is not just for fantasy and sci-fi - world-building is important, no matter what genre you write in.

And then of course your plot. I am not saying you have to plot. We're going to talk about plotting later, but just kind of think about what the big guidepost scenes might be, even if you don't know what order they fall on yet. What big moments do you see happening for these characters? And remember, pun intended, none of this needs to be set in stone. You can always change it later. So don't put too much pressure on yourself. We are anti perfectionists here. You want to stay flexible, write down everything, and just make a big mess.

So the mistake writers make that I think results in fear, that kind of crippling fear where you just eventually give up, is that when they start writing a book, they pull out the small tools. They take this giant hunk of marble that doesn't look like anything and they get to work with brushes and these teeny tiny scalpels, and they're scratching away the marble and brushing away at the marble and they do this and they do this and they do this and the hunk of marble still just looks like a hunk of marble. And that's when they give up. Do not do this — those tiny tools, those little brushes, and those little scalpels, those are for revising and editing. So put them away for now. And tell yourself that they are there for when you have a finished draft that's a big, old mess, a hunk of marble that started to take on some kind of shape. And then you're going to pull on these little tools and get to work on the nitty-gritty details.

Step 2. Finding a plot in premise

So now onto actually finding a bit of a plot in your premise.

Plotter vs. pantser

I wanted to say a few words about the whole ‘plotters versus pantsers’ thing because I just have a lot of thoughts on this. If you don't know, I'm sure you all do, but plotting or plotters refers to people who outline their novels before they write the draft, and pansters are people who just write the draft with no idea of the plot in mind. Sometimes we also call this discovery writing. And there's a fun kind of duality in the writing community. Like you're either a plotter or a pantser, or maybe I think sometimes people call themselves plantsers.

But the thing is, I don't think that the spectrum is quite this neat. All writers and novelists plot, we just do it at different stages in the writing process. Some of us do it first and some of us do it while we're drafting. If you're a pantser you are kind of plotting as you're drafting - your plot might be a mess, but it's still plot. And then sometimes we do the plot afterward.

I usually plot ahead of time, but one time I wrote a book and I finished the first draft and then I was like, ‘Okay, I need to give this some structure.’ And I did the plotting after the fact. Again, this is where you should just follow your gut. And do whatever feels right for you. So don't feel like you have to outline, don't feel like outlining is bad and it's going to restrict you. Whichever one sounds good to you is what you should do. And if you want to try some flexible combination of both, that's great. Lots of writers do that.

Now I do call myself a plotter because, as I mentioned, I do a lot of ghostwriting and I've done a lot of intellectual property projects for publishers, which is where they have an idea for a book and they hire me to write it. And those jobs, IP work and ghostwriting, require me to generate very detailed scene-by-scene outlines for clients and for publishers so I don't have a choice in that matter. I have to be able to be an outliner. And I can tell you that no matter how many people are working on a book and on an outline, no matter how detailed that outline is, it is an absolute fact that while you're writing the first draft, at some point you are going to veer away from the outline. This is expected. I have never had a publisher or a client get mad at me when this happens, because it's honestly always a good thing. I've never a hundred percent stuck to an outline.

And that's why I think the term ‘discovery writing’ isn't just for pantsers. We all discover more about our characters when we write the first draft, no matter how detailed and thorough we are in laying out our plot before. They become more real and vivid and you know, maybe they're a little bit different than we originally thought, maybe they had a secret that we didn't realize they were carrying. And if we're doing it right, eventually our characters kind of gently take the wheel and start driving that plot themselves. And they might start off-roading it. We should embrace this and let them take the wheel. This is their story now and you're just following it along. So don't let it scare you if you feel like this is happening to you, because in my opinion, this is a really great thing. And I just want to say, don't try or worry about defining yourself as a plotter or a pantser. You're an author, you're putting a book together and the process is just going to be messy.

Character or plot driven?

And then another kind of debate I see happen quite a lot is whether a book is character driven or plot driven. The thing that I think is just kind of a little bit silly about this is that books should be both. Character and plot are things that we should really consider separately after the brainstorming phase because the plot is your character's journey. So really it doesn't matter which of these things came first. You want your book to be both, the character should be driving the plot. There is a reason that this protagonist is the star of this adventure that you are writing.

So what I want to do is talk to you a little bit about very specifically how I took an idea and I turned it into one of my novels. The reason I chose my novel Spell and Spindle is because the idea I had was super, super vague. All it was was that marionettes have souls. That was it.

Idea: Spell and Spindle

Dolls have always really creeped me out, especially puppets. When I was a kid, I watched a lot of Nick at Nite and I loved Alfred Hitchcock Presents and there's this one episode, I believe it starred Jessica Tandy, and it's called ‘The Glass Eye’ and it was about a woman who exchanged romantic letters with a ventriloquist. And then, in the end, she realizes that he, the ventriloquist, was actually the puppet and the puppet was the ventriloquist and it freaked her out and it freaked me out. It just kind of stuck with me as a kid. And I think that was the seed for this book which bloomed decades later.

Ever since then, I have always loved a good creepy doll-possession story or horror movie. And also I always wanted to write my own kind of Brothers Grimm, dark fairytale.

Premise: Spell and Spindle

So the next step, when I had this idea was to start asking myself some questions. I asked myself who specifically is the story about, it can't just be about marionettes in general, who is this about, and what do they want? Because your premise is going to be your idea, but to have conflict you have to have a character who wants something.

So for me, with Spell and Spindle, I think my idea turned into a premise when I thought, okay, maybe these marionettes have souls, but that's not enough for them. They want to be real children. Maybe they can even swap souls with children. And I kind of let this idea, this premise percolate in my brain for a few months. And I eventually started to see two characters, a boy named Chance, and a marionette girl named Penny. And they swapped so that Chance was trapped in the marionette body and Penny had mobility and autonomy for the first time in Chance's body. And I think that was when my idea turned into a premise, because obviously there is some conflict in there.

Plot: Spell and Spindle

So now the next step. I had an idea and it had some conflict to make it a plot. I think you need to next figure out what the stakes are if your characters fail to get what they want. In other words, what awful thing will happen to your characters if they don't overcome this conflict? Why do my characters want these goals? And what's the motivation? So, if you are in that beginning stage and you need to start a brainstorming document, but you don't know what to write about. Start with these questions, ask yourself this and let yourself run with them.

In Spell and Spindle, I wanted to simplify things by giving both of my characters the same wants. So both Chance and Penny want adventure and they both want to be understood and they're separated while their souls are swapped. One gets kidnapped, the other one sets off on a rescue mission. It's pretty simple.

In the beginning, Chance (the boy) is about to move from the city to the suburbs because of his father's new job. And he is just positive that his life is going to be unbearably boring. He also feels really deeply misunderstood by his relentlessly optimistic family, because he is a serious pessimist and he longs to find someone who will understand him. As I said, they have the same situation. Penny, the marionette, is facing life in storage when her museum closes and life in a box is also going to be unbearable. The only way anyone can hear Penny's thoughts is to touch her strings, but she's been high on the shelf in a museum for years and so she longs for someone who can understand her.

Now once Chance finds Penny and they begin to communicate and they form a friendship, they make a plan to run away together and join the carnival because they both want adventure and they want to escape their boring lives. As they practice their act, they learn that they can swap souls, swap places, which they think is really cool and interesting. And then their plan to run away is thwarted when the puppeteer, the antagonist of the story who built Penny, returns and steals the marionette but doesn't realize that Chance's soul is still in.

So Chance is trapped in a marionette's body and he's at the mercy of this evil puppeteer, which is not at all the kind of adventure that he wanted, and Penny is free, but she's in Chance's body. And so she sets off to rescue him from the puppeteer, but she knows the whole time that ultimately she'll have to sacrifice her newfound freedom if she really wants to save him. So the stakes are really high here for both of them — Chance might be stuck in a doll's body forever and the only way Penny can save him is by giving up her own freedom.

Story: Spell and Spindle

And that brings me to the story. So what makes the difference between a plot and a story? I think the better question is: what's the point? That might sound kind of harsh, but I think it's a question every author should ask themselves about every book they write.

We can all probably sit here and name a ton of books or shows or movies that are similar; a hero is on a quest to find a thing or save a person or stop a villain; a detective is trying to solve a crime, the stakes are life and death. Great. We love those stories, but why do we really care? What's the point? What makes one story out of a million with kind of the same plot, actually special?

It’s the characters, obviously. We will follow believable, flawed, entertaining, real, authentic characters who feel like people we know anyway. And it's in your characters, in their struggles, where you're going to find the themes of your story, because the truth is story tropes like boy meets girl, or hero saves the world from ending never get old. We love them. They only feel derivative when there's nothing special about the characters.

So for Spell and Spindle, the most prominent character trait I had in mind for both Penny and Chance from the beginning is that they are both supreme pessimists. I love their dark little souls. They both just fully believed the worst would always happen and that made it so fun to write about how they handled it when the worst did in fact happen to them. And the thematic questions I found myself asking about this were what does it take to make someone forget their own identity? or what kind of person sacrifices everything to save another?

I imagined Chance just completely immobile and mute in this puppet body, gradually forgetting he was ever a real boy. And I imagined Penny getting her first taste of freedom and experiencing the joy of emotions and movement and being human and how tempting it would be for her to just leave Chance to his fate.

Those are the kinds of big emotional questions that will hopefully get the reader to care about the conflict. And to me, a story is a plot that readers care about.

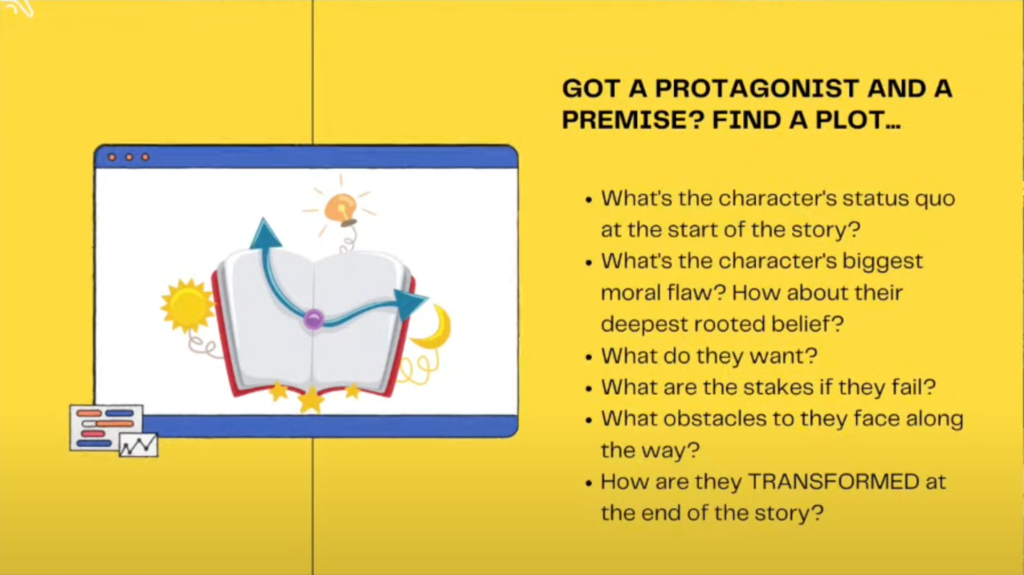

Got a protagonist and a premise? Find a plot

So if you have a premise and you have a protagonist, no matter how big this is in your mind, you can start asking yourself these questions to find your plot. I do have a super short SkillShare course that walks through finding a plot by asking yourself about your characters’ beliefs, but I’m going to talk you through the short version here.

You start off with a description of your main character at the beginning of the story, her personality, and her current situation.

Take note of her deepest-rooted beliefs. Your character's deepest belief is the one that results in her biggest flaw. And only when that belief is shattered, will she be able to overcome that flaw. That's what gives her a satisfying character transformation.

You want to ask yourself, what are the stakes for her? What terrible thing will happen if she doesn't achieve her goal? The higher the stakes for her, the better.

Of course, you want to ask yourself what obstacles will she face along the way? And the biggest, baddest obstacle that you can think of, that's going to probably be the climax of your book. The moment that forces her to confront that deepest rooted belief of hers that maybe isn't quite as true as she thought and then finally overcome her flaw. How does she do that? And what does it cost her?

And then of course, last but not least, you want to think about how this changes her? How does she transform into a different person?

Every character is different at the end of the story than at the beginning. And that's your character arc and it's also the core of your plot.

For those who hate plotting

So when I have a client who just hates plotting and they don't want to have any part of it, this is what I recommend they do in the beginning.

You've probably heard about this therapeutic exercise of writing a letter to your past self, so you would do this from your protagonist's point of view at the end of the story, and have them write a letter to themselves at the beginning of the story. And this is not about rehashing plot points. Don't worry about the plot at all. This is 100% focused on emotions.

I mean imagine all of us right now if we were to write a letter to ourselves in February of 2020, right before the pandemic really kind of exploded. What would we say to ourselves? This letter would be more about how we could better emotionally prepare for what's coming and less a timeline of lockdowns and advice to buy toilet paper and get familiar with Zoom. So it's all very emotional, don't worry about the plot now.

For those who love to plot

For clients who really love plot, I recommend writing a book description. I love doing this because it gets me excited about my story. And this is what I turn to every time I feel stuck. When I'm brainstorming an idea I use this formula, because I just kind of find the idea of plugging things into these brackets really satisfying and it helps me just flush out the idea a lot more.

[CHARACTER] was [STATUS QUO] until [INCITING] happens, and [HERE’S HOW THAT AFFECTS THE MAIN CHARACTER’S LIFE].

Now [CHARACTER] must [GOAL] despite [CONFLICT] or else [CONSEQUENCE].

When you're doing this, don't worry about making it voicey or even grammatically correct. The point is just to get these beats of the story onto the page.

Now in my course, I actually walked through each of these bracketed components to create a description for a fake novel called Jack Versus the Water Aliens and I designed a cover for it and everything. I had a lot of fun with this, and this is the very, very first version of the description I got when I filled out that formula.

The reclusive Jack is working up the courage to ask Jill to go to the uphill dance until aquatic aliens crash-land in their small town’s lake and claim Jill is the long lost heir to their planet’s sovereign power which is now being challenged by a rival family, throwing Jack's plans for Homecoming King and Queen.

Now Jack must prove the aliens have the wrong girl despite increasing proof that Jill might be a little less human than everyone thought or else they'll take her from Earth forever, and Jack can kiss his Homecoming court dreams goodbye.

This is what I mean by messy. This is nothing I would actually want to be printed on the jacket or back cover of my book. And it's definitely not anything I would use in a query letter or anything like that. It's very clunky and it lacks a voice. You can just tell it needs a lot of finessing. But I did say we are going to make a mess at the beginning of this process, and that's what this is. If I were to one day write this book this pitch would change. As I said, your outline might change, your pitch might change, you might figure out that the core conflict of your story is something else entirely. But the point is it got you started, it gave you a point to start from so that you had the confidence to start writing.

Step 3. Practical tips to start writing your book

And now what about the client who doesn't feel ready to dive into their protagonist's inner, emotional turmoil yet? So the therapeutic letter, that's not for them. And what if this client also looks at this formula and says, ‘Oh, I don't know what the stakes are. I don't know my conflict.’ If you're still in an earlier phase in your brainstorming and neither of these sound good to you, how do you find your way to starting?

Talk out loud

First of all, talk to yourself. I'm not kidding. And I hope that doesn't sound too flippant or too easy of an answer. Sometimes you really need to say it out loud. The amount of time I spend walking around in this apartment, especially last year, talking to myself or talking to my dog, is a lot. And it's not just because of quarantine. If you have a friend, like I said, who's a writer especially, or just a friend who’s a prolific reader and would love to talk about story ideas, talk to them and let yourself ramble and explain this. But if you don't have anyone or if you have a cat or a dog, talk to them about it.

I know having a sounding board can be really great, and you have all probably heard that writing by hand activates a different part of your brain than typing. I know that's true. And I think the same can be said for talking out loud. It's just not the same when we keep it all in our heads. Something changes when we actually say the words. So you really, really want to start talking out loud because it's going to lead to revelations that you wouldn't have had if you just kept it inside.

Use dictation

If you want the best of both worlds, I can't recommend using dictation features enough. Both Google Docs and Microsoft Word have dictation or voice typing. You don't need any special software at all, you just click the button, talk out loud and it's accurate enough. There are going to be some typos, but it's fine. Just let yourself ramble and document everything that you're saying. It’s really kind of scary to me how often this has happened, and I know this happens to other writers too, where we think of an amazing idea for our book, like something that's going to fix our plot, and 15 minutes later, we can't remember it or we remember it. It's really scary to lose those revelations so just use the dictation features and document everything.

Create small habits

Now as far as actually starting to establish a writing process, especially if you've never done it before, the best thing you can do is create small habits. Almost everybody on earth by now has read Atomic Habits and if you have you’ll get what I’m going for here. ‘Writing a novel’ is such a huge goal, much like ‘I want to run a marathon’. You don't just show up to a marathon at the starting line and start running and go for 20 miles - you need to train and you start with smaller runs and you work your way up to it over several months. The same goes here. Just start with small habits that you know you can achieve.

Perhaps every night before bed I will dictate and brainstorm for 10 minutes, or during lunch I'll write 100 words. Just however short and easy you need it to be to make sure you know you can do it. Every time you do it, that feeling of success is going to spark the motivation for you to do it again and again, and to make it a habit.

If you try something and it's not working for you and you feel like you're forcing it, then just try something else. And when you do find something that sticks from there, just slowly start expanding it. Your 10-minute writing session during lunch, maybe turns into 15 minutes or your brainstorming session before bed goes from 20 minutes to 30 minutes and before you know it, you have a real writing routine.

Find YOUR process

And then finally, and maybe most importantly, like I just said, every writer is different, every book is different. My process and routines changed from book to book and there's a lot of information out there about how to write a book. I mean, you're watching a webinar on it, so I know that you know this. You're going to hear a lot of advice. You're going to see a lot of software and courses and all kinds of things to help you with it. These things are all great, but if they feel overwhelming to you, then just know you don't need any of them. I have always said that.

As much as I learned in the early stages for me by reading editors’ and agents’ blogs or by following authors and reading their blogs, the greatest writing course I ever took was just actually finishing my first draft. I learned more writing a first draft of a book for the first time than any other experience, any YouTube video, any course.

And remember, I'm saying this to you as a teacher who teaches writing workshops. I have courses. But I'm telling you, you don't actually need any of that. They might supplement, they might help you, but the actual process of figuring out what works for you, getting your hands dirty, and taking out the hammer and chisel, that's going to be the greatest learning experience. My very first book was never published. Nobody has ever read it except for the agents that rejected it. And to me, all 80,000 of those words are not at all wasted because of how much I learned from it and how much I grew, and how much better I got with the books I wrote after that.

Writers on YouTube and on social media everywhere have very strong opinions about writing and I think too often the same notions are spread like ‘this is the best way to do this,’ or ‘if you do this, you're not a real writer’, and that can be really harmful. I'll just use this as an example.

I love Stephen King. I have nothing but respect for the man. And I know his memoir On Writing came out ages ago and maybe his opinion on this has changed, but he has that one comment in that memoir about how plotting is for dullards because he is a pantser and it always irked me because it's not true. Pantsing works phenomenally well for Stephen King. Being a meticulous plotter and researcher who takes years and years to write a book works really well for Dan Brown. And until I sell a couple hundred million copies of a book, who am I to judge either of these writers and the way they write a book, everybody is going to have their own routine and their own process.

So remember, nothing about this is set in stone. You just have to figure out that works for you and that’s the most important piece of advice I can give.