Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

The Three-Act Structure: The King of Story Structures

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →The three-act structure is perhaps the most common technique in the English-speaking world for plotting stories — widely used by screenwriters and novelists. It digs deep into the popular notion that a story must have a beginning, middle, and end and goes even further, defining specific plot events that must take place at each stage.

In this post, we dissect the three acts and each of their plot points — using three-act structure examples from popular culture to illustrate each point.

Let’s begin! In three, two, one...

FREE OUTLINING APP

Reedsy Studio

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

What is the three-act structure?

The three-act structure is a model used in narrative fiction that divides a story into three parts (or acts), often called the Setup, the Confrontation, and the Resolution. An old dramatic principle, the three-act structure can be traced back to Aristotle’s Poetics, in which he defines it as one of the five key elements of tragedy.

According to Aristotle, each act should be bridged by a beat that sends the narrative in a different direction. His belief was that stories must be a chain of cause-and-effect beats: each scene must lead into what happens next and not be a standalone "episode."

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Now that we know the three-act structure, let’s dive into how it works.

Common story beats in the three-act structure

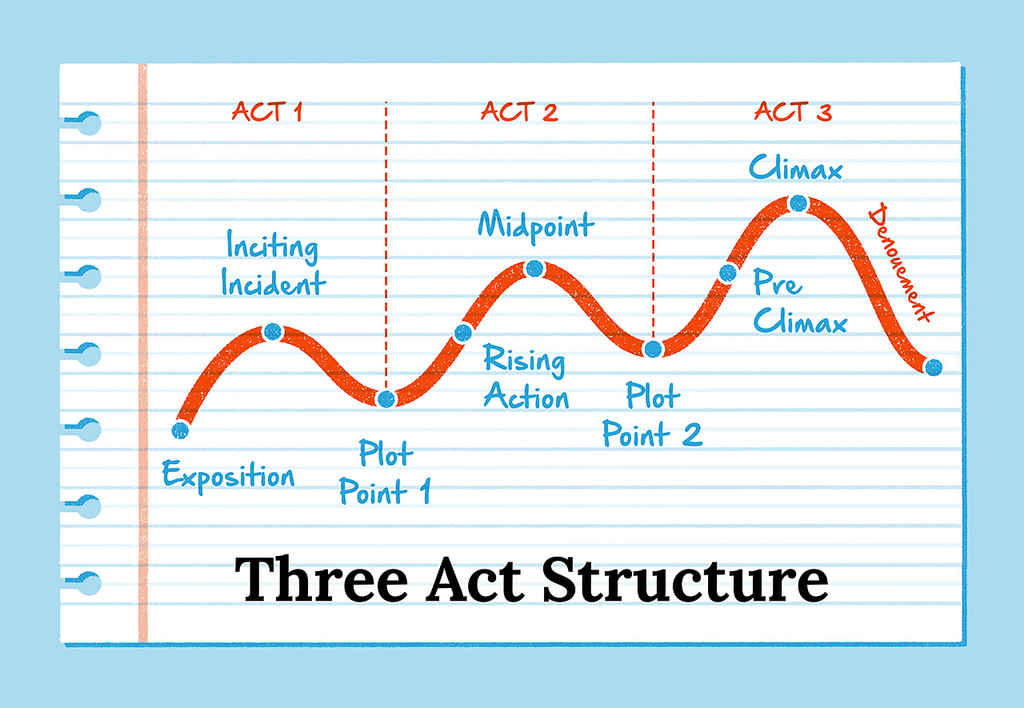

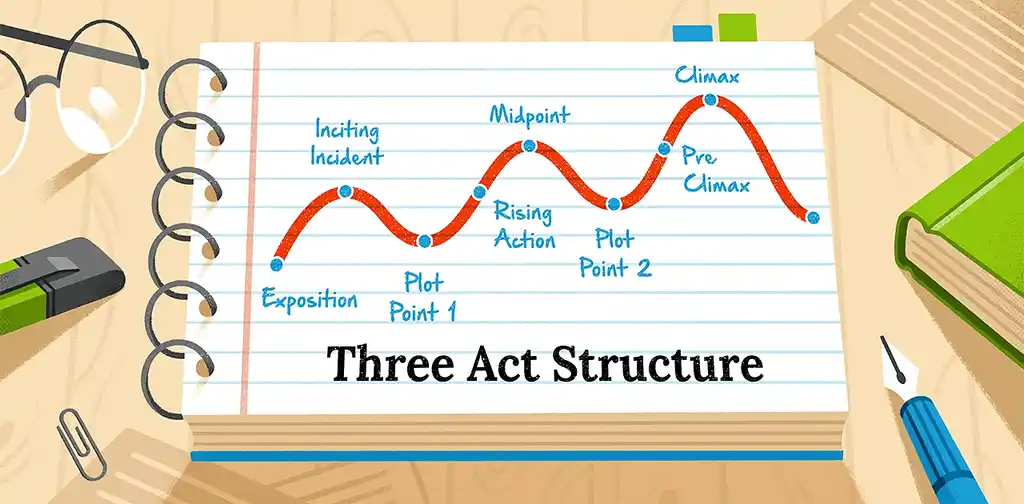

To help us better understand writers might use this structure to construct a story, we’ll need to dig deeper into what makes up each of the acts. Here is what you’ll find in the three-act structure:

- Act 1: Setup – Exposition, Inciting Incident, Plot Point One

- Act 2: Confrontation – Rising Action, Midpoint, Plot Point Two

- Act 3: Resolution – Pre-Climax, Climax, Denouement

To help you see this structure in action, we’ll use 1939’s The Wizard of Oz as an example as we unpack all nine story beats.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

Act One: The Setup

Despite being one of three sections in a plot, Act One typically lasts for the first quarter of the story.

Exposition

The exposition is all about setting the stage. The reader (or audience) should get an idea of:

- who your protagonist is,

- what their everyday life is like,

- and what’s important to them.

Of course, nobody’s life is perfect — so the exposition should give readers a sense of the main character's current desires and the challenges that prevent them from getting what they want in life

Example: Dorothy dreams of somewhere over the rainbow

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s home life in Kansas forms the bulk of the exposition. We see that her family are hard-working farmers and that she has a dog she cares for called Toto. We learn that Dorothy feels misunderstood and under-appreciated.

Q: What techniques can authors use to hook readers from the first page?

Suggested answer

Start with your main character doing something somewhere and start in the middle of the action. If there is a hurricane coming, have them board up the windows of their home. If they are dreading an upcoming test at school, have them look over their last test grades and worry that this next test won't be any different.

You want to avoid "talking heads." This is what publishers think when there is dialogue going on between characters, and because there is no sense of "place" or "setting", the story comes off as characters "talking in space." This is why you want the characters to be somewhere and do something in every new scene you draft, not just the opening.

Readers like to visualize the action in a book, even if the "action" is inward. So start off with a visual picture of your main character doing something, and this should hook readers.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I recall reading a memoir of a famous tennis player and he started it by plunging the reader into his experience of facing a relentless machine shooting balls across the net to him -- all the fatigue and pressure of trying to become a pro was encapsulated in the scene. Much more interesting than starting it with when and where he was born etc.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Inciting Incident

This is the catalyst that sets the protagonist’s adventure in motion. The inciting incident is a crucial beat in the three-act story structure: without it, the story in question wouldn’t exist. The inciting incident proposes a journey to the protagonist that could help them change their situation and achieve their goal.

Author and editor Kristen Kieffer suggests asking yourself the following questions to help you craft the inciting incident:

- How is my protagonist dissatisfied with their life?

- What would it take for my protagonist to find satisfaction? (This is their goal).

- What are my protagonist’s biggest fears and character flaws?

- How would the actions that my protagonist needs to take to find satisfaction force them to confront their fears and/or flaws?

The catalyst is often called the “call to adventure” and asks your protagonist to push themselves out of their comfort zone. This is where Luke Skywalker receives a distress call from Princess Leia, where Tony Stark is captured by terrorists at the start of Iron Man.

Will the protagonist rise to the challenge, or will they “resist the call” to adventure? After all, going on this journey will have consequences for themselves and those around them. What’s at stake if they fail?

Q: What is the most crucial piece of backstory an author should understand about their protagonist before beginning a novel?

Suggested answer

Whether in the backstory or in the current action of the book, once the reader starts reading, the author should know what their character wants. It can be a long-held desire or something new, based on changed circumstances.

There has to be a motivation and drive in the character. Or if there isn't any, and that is sort of the point of the book, you want to let the reader know why and what in their past has made them the way they are. This sort of "motivation" is a good thing to search for in each character. What has shaped them to do what they do and behave the way they behave in the story? They must stay "in character" throughout the book unless some sort of inner or outer impetus has forced them or inspired them to change their ways.

So this most crucial piece of backstory might be why your protagonist behaves the way they do, what motivates them and why, and what they want.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Depending on the character, and their core fears and flaws, you may need to dedicate a few scenes to raise the stakes so that the character has no choice but to accept.

Not sure what those flaws and fears are yet? Don't worry! Our handy character profile template will help you find out.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

Example: A twister takes Dorothy on an adventure

Dorothy runs away from home and encounters a professor who encourages her to go home. Upon her return, a tornado causes Dorothy to be struck in the head by a window. Her home has been whisked off to the Land of Oz when she wakes up.

Plot Point One

It’s full speed ahead now! No more hemming and hawing for your character: the First Plot Point represents the protagonist’s decision to engage with whatever action the inciting incident has created. It’s when Bilbo Baggins decides to join Gandalf and the band of dwarves for an epic adventure in The Hobbit.

In some stories, the Inciting Incident and Plot Point One happen in the same scene. For instance, in The Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen’s sister is selected as a ‘tribute’ in the titular games (inciting incident), and Katniss immediately volunteers to take her place (plot point one).

Think of the First Plot Point as the springboard that launches your character into Act Two.

Q: Can I break traditional story structure rules and still write a good book?

Suggested answer

The quick answer to this is yes!

The longer answer is that, in order to break the rules of traditional story structure, you must first understand them. Authors who are successful at going completely outside of the 'norm' in storytelling and writing really know their stuff. They understand why the 'rules' are in place, and then they work hard to go against them in a meaningful, intentional, and acceptable way. If you look at experimental literary fiction, for example, you'll see a lot fewer examples than, say, the typical commercial fiction novel. In commercial fiction, there are certain expectations in terms of style, voice, tropes, structure, etc. Readers go to these types of novels to have their reading desires and expectations fulfilled. But that doesn't mean you can't surprise them every now and again.

The great thing about writing fiction is that you can do whatever you want--the sky is the limit. Structure, style, etc. can be played around with, but it must be exquisitely executed. And to achieve that, you must first know the rules like the back of your hand and master them.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking the traditional story structure is best done after you have a few books under your belt and are a seasoned author, especially if you are seeking a traditional publisher. There is enough risk for publishers to take a chance on a new author without the added risk of trying to push something that is out of the box. There are many people in the publishing chain of approval, and trying to sell the idea to the bulk of a publishing staff can be challenging if the author has no track record of sales to speak of.

When starting out, it really is a good idea to "play by the rules" if and when possible. That doesn't mean your book will not be "good" if you break the rules, but it's risky. Because the reality is that not all "good" books get book deals. This business is very subjective, and publishers run for-profit businesses, and they want and expect to make money on their books. Unfortunately, every decision regarding books that get chosen for publication is not based on artistic merit alone.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: Dorothy chooses to ease on down the road

Frightened and confused, Dorothy wants to go home and is told by Glinda the Good Witch that the only way is to follow the Yellow Brick Road to the Emerald City where The Wizard lives. Dorothy decides to follow the road, and it’s established the Wicked Witch will try to stop her.

Act Two: Confrontation

Typically the longest of all three sections: Act Two usually comprises the second and third quarters of the story.

Rising Action

Here’s the part where Dorothy waltzes down the Yellow Brick Road to meet Oz who sends her home without a hitch, right?

Nope. This is where the protagonist’s journey — or the pursuit of their goal — begins to take form and where they first encounter roadblocks. The protagonist learns their new surroundings and starts understanding the challenges that lay before them. This is the part of the story where you should better acquaint readers with the rest of the cast (both friends and foes) and the primary antagonist. You will also elaborate on the story’s overarching conflict (whether it’s a person or a thing).

As the protagonist learns more about the road ahead, they’ll change and adapt to have a better chance of achieving their goal. In this way, the main character is usually more reactionary than proactive in the Rising Action phase.

Example: Dorothy makes friends and discovers roadblocks

Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and Lion. They travel down the Yellow Brick Road, encountering obstacles such as apple-throwing trees and sleep-inducing poppies.

Midpoint

It’s no big surprise that the Midpoint takes place at… drumroll, please… the middle of the story! A significant event should occur here, usually involving something going horribly wrong.

Q: What is the 'saggy middle' in storytelling, and how do I fix it?

Suggested answer

A 'saggy middle' occurs when a story loses momentum, tension, and trajectory right around the midpoint of the story. A story can lose it's steam (and with it, a reader's interest) when character arcs stall, plots become muddled and messy, and subplots abound with no sense of direction. Stories can also sag if they fill pages with descriptive information that does little to engage the characters or further the story arc.

But never fear! This is a very fixable problem. First, think about the ideas at the heart of your story. What story do you want to tell? What lies at its core?

With that in mind, review the midsection of your story with an eye to the issues described above. Once you identify your problem areas, you can set about rewriting with a goal of increasing the tension by increasing the stakes for your characters, adding new conflicts/problems for characters to explore, cutting excess descriptions and sections that over-explain character motivations/backgrounds/actions, and tightening sections that do little to further the core plot that drives the story.

Erin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I tend to see saggy middles show up when authors are adhereing to a strick timeline of events, rather than sharing scenes that pull the plot forward. For example, I edit a lot of middle grade fiction and a saggy middle might include multiple chapters that open with the protagonist waking up and close with the protagonist going to bed. Or going to school, then getting home after. Readers don't need the day-by-day minutia to get from one scene to the next.

Instead, focus on what will pull your plot forward, and think of your middle as scenes rather than a timeline that gets you from point A to point B.

I usually suggest that authors step away from the manuscript and instead write scenes, even if out of order, that they need for their story to make sense. When finished, they can line them up in order, and then fill in the blanks for a much faster-paced and cohesive middle. Even if you don't have a saggy middle, this is an effective practice for planning and plotting purposes.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The 'saggy middle' of a story is the part of the story where the inciting incident - or the problem in the story - has already happened, but the ending, or climax and resolution, is nowhere in sight. It really does fall in the middle of the story.

There are several ways to handle this issue:

*Use a subplot with the main character or a secondary character that will still need its own resolution and will bring in another layer of trouble for your character[s]. In The Wizard of Oz, each of Dorothy's three friends suddenly has their own problems. The scarecrow loses his stuffing, for instance, so the storyline shifts for a bit from Dorothy's desire to get back to Kansas - her hero's journey and the through line of the book - and takes a slight turn to focus on the scarecrow and friends before turning back to Dorothy's main plot line again of getting home.

*Raise the stakes - create even more trouble for your character and/or make the result[s] of the trouble even more dire. In the book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, first, Mrs. Morris the cat is sent to the hospital, then humans that are Harry's friends, then finally, Ginny is in trouble, who will end up being Harry's love interest. So the stakes and problems keep building all the way through the book until the final climactic scene.

*Use what is called a 'midpoint reversal': This is where the character changes his mind about the issue and is not opposed to it any longer. In the movie "Tootsie", at first, Michael does not want to pretend to be a woman to get work, but by the middle, he loves the idea of pretending to be a woman and wants to take things even further, which causes friction between Michael and his agent. So more trouble occurs because of this mindset reversal, which then leads the book to its satisfying conclusion.

You don't have to use all of these techniques, but try one out in the middle of your book, and see which one works best for your own story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Return to the protagonist’s main goal to establish what this Midpoint event should be. What must happen for them to feel that their goal is being directly threatened? What could make the character even more acutely aware of the stakes at hand?

Example: The Gang meets up with The Wizard

Dorothy finally reaches the Emerald City and meets with The Wizard, who is a big disappointment. He initially refuses to meet with them, and when he eventually does, he declines to help them until they bring him the Wicked Witch’s broomstick.

Free Download: Three-Act Structure Template

Effortlessly plot your story with our customizable template. Enter your email, and we'll send it to you right away.

Plot Point Two

Our poor protagonist has fallen on hard times. They thought they were making headway on their goal, and then the Midpoint came and threw them off their rhythm.

Give them some time to reflect on the story’s conflict here. The aftermath of the Midpoint crisis will force the protagonist to pivot from being a “passenger” to a more proactive force to be reckoned with. You might want to plan a sequence where the main character’s resolve is bolstered through productive progress on their journey’s goal. Think of Plot Point Two as the pep talk your character needs to stand up straight and get ready to meet their antagonist head-on. They’ll need this confidence to handle what comes next…

Example: The decision to face the Wicked Witch

Dorothy must decide whether to risk heading to the Wicked Witch’s castle or give up on her chance of going home. She and her companions decide to confront the witch.

Act Three: Resolution

The final act typically takes up a quarter of the story — often less.

Pre-Climax

Even the strongest knight has weak spots in their armor: their deep-rooted fears and flaws. As the protagonist has been gearing up to meet the antagonist head-on, their main foe has also been getting stronger and is now ready for battle.

Also called “The Dark Night of the Soul,” the pre-climax starts with the final clash between the protagonist and the antagonist. We’ve experienced the entire journey with the main character — but this is where we get our first glimpse of the antagonist’s true strength, which usually catches the main character off guard. Even though most readers know that the protagonist typically wins the day, we should have some doubt here about how the last act will play out and if the main character will be okay.

Q: What is the single most important piece of advice for first-time novelists?

Suggested answer

Write the story you want to write, need to write--and want to read. Don't think about or worry about market trends, or how you will position your book on the market, or writing a book that will blow up on BookTok. A novel is a marathon, and in order to see it all the way through, you have to love your story (you can dislike some of your own characters of course, but you need to be deeply passionate about the overall story you are telling). In practical terms, by the time you write, revise, and publish your novel, it's likely that overall publishing trends will have shifted anyway. Write the book you want to write--things like what readers want, what publishers want, what agents want, can come later!

Kristen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Read many books in your genre and look for why you like that particular book or don't like it. Get a feel for what works and what doesn't. Try to read books that sold well and were published in the last 5-10 years. Publishing norms change and styles change with time.

For instance, in the past, much time was spent setting up the story, and many opening paragraphs may have been spent describing the scenery and visual elements. While those elements are still important, modern books move at a much faster pace and spend less time on these elements by using sentences of description woven into the narrative rather than information dumps and blocks of long description that can slow the pace.

So, reading current books in your genre is the best way to learn writing methods yourself.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: All seems to be lost

While on the way to the Wicked Witch’s castle, Dorothy is captured. The Witch finds out that the ruby slippers can’t be taken against Dorothy’s will while she’s alive, so she sets an hourglass and threatens that Dorothy will die when it runs out.

Climax

The climax signifies the final moments of the story’s overarching conflict. Since the antagonist has just hit the protagonist where it hurts in the previous beat, the protagonist has to lick their wounds. Then they face off again, and the main character finally ends the conflict.

The climax itself is normally contained to a single scene, while the pre-climax typically lasts longer and might stretch over a sequence of events.

Example: “I’m melting!”

Dorothy throws a bucket of water on the Scarecrow, who has been set alight. She ends up accidentally dousing the Witch, who melts into a puddle. The guards hand the Witch’s broom to Dorothy.

Denouement

Finally, the dust settles. If the protagonist’s goal is not immediately obtained during the Climax, the denouement is where this should be achieved (or redefined, if their goal changed during Act Three). Along with this, the denouement should also:

- Fulfill any promises made to the reader. Check out this post on Chekhov’s Gun to learn more about this;

- Tie up significant loose ends;

- Underscore the theme; and

- Release the tension built up during the climactic sequences of events.

If you want to learn more about nailing your story’s resolution, check out this post on how to end a story.

Example: Everyone gets what they need

The Scarecrow receives a diploma, the Tin Man receives a “heart,” and the Lion receives a medal of valor. The Good Witch explains that Dorothy has always had the power to go home; she just didn’t tell her earlier because she wouldn’t have believed it. Dorothy taps her ruby slippers and heads back to Kansas to greet her family lovingly.

When should you use it?

The three-act structure is just one way to think about a story, so writers shouldn’t feel limited. The benefit of using the three-act structure is that it will help ensure that every scene starts and end with a clear purpose and direction. Even if you don't start outlining your novel with it, if you find yourself struck by pacing issues, it's often useful to fit your story into the three-act structure to see why that might be.

Q: How can writers incorporate popular story models like The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat while maintaining originality and creativity in their writing?

Suggested answer

Saving the cat can come into play in many forms. At the end of the day, readers want to root for likable heroes. If you make your main character sympathetic in some way, that sort of ticks the "saving the cat" box off nicely.

A journey can comprise so many forms. It can be a literal journey Dorothy takes from Kansas to Oz and then back again in The Wizard of Oz, or it can be an inner journey of deciding to take charge of his life and not let others make his decisions for him, as we see with Macon Leary in the book The Accidental Tourist.

As long as your "save the cat" moment and "hero's journey" uses unique ideas that have not become cliché, you should be fine.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No matter what type of novel you're writing, we've got resources for you! Check out the rest of this guide for more articles breaking down common story structures, and sign up for our ultimate novel writing course for even more tips to get you started.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

7 responses

Adron J. Smitley says:

02/07/2018 – 06:40

Excellent advice! I actually just published a book for writers and nanowrimos to help both Plotter and Pantser write their novels called, "Pen the sword: the universal plot skeleton of every story ever told" its free with kindle unlimited. walks you through every step of plotting your novel :-)

Lita Brooker says:

03/07/2018 – 19:59

Such a useful article. Thank you.

Ryan Monahan says:

04/07/2018 – 17:49

Very informative! Would you be able to make an article or two about alternatives to the 3-Act Structure (maybe even compare/contrast them) and how the various story structures are used for series?

↪️ Reedsy replied:

05/07/2018 – 14:52

We're definitely working on more structure articles like this to explore different structure options :)

Marie Robinson says:

08/07/2018 – 14:38

I've recently started thinking about structure in 4 acts instead of 3. It's actually exactly the same structure, but you break Act II up at the midpoint and make that second half a separate act. This had helped me think of that middle half of the story in more manageable 25% chunks, and it has greatly reduced that "muddy middle" problem that I know is not unique to me.

Svetlana Rosemond says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

I'm planning on writing a series of blog posts and I was researching the 3AS and came across your blog. Would you mind if I quoted and linked back to it ? Here is my blog.

↪️ Reedsy replied:

08/05/2019 – 12:29

Of course! We'd be delighted if you did :) Thanks so much!