Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

The Seven-Point Story Structure: From Idea to Plot in 5 Steps

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →The Seven-Point structure is a relatively new player in the world of story structures, but it’s here’s to stay. It was first popularized by sci-fi author and RPG-enthusiast Dan Wells at the 2013 Life, the Universe, & Everything conference. He took the structure outlined in the Star Trek Roleplaying Game Narrator’s Guide and turned it into a system that he and many other authors claim to have used to build their novels.

So what exactly is the Seven-Point structure, and how can you use it to craft your own exciting tale? We’re giving you the full breakdown, with demonstrations from the YA hit, The Hunger Games (spoilers ahead).

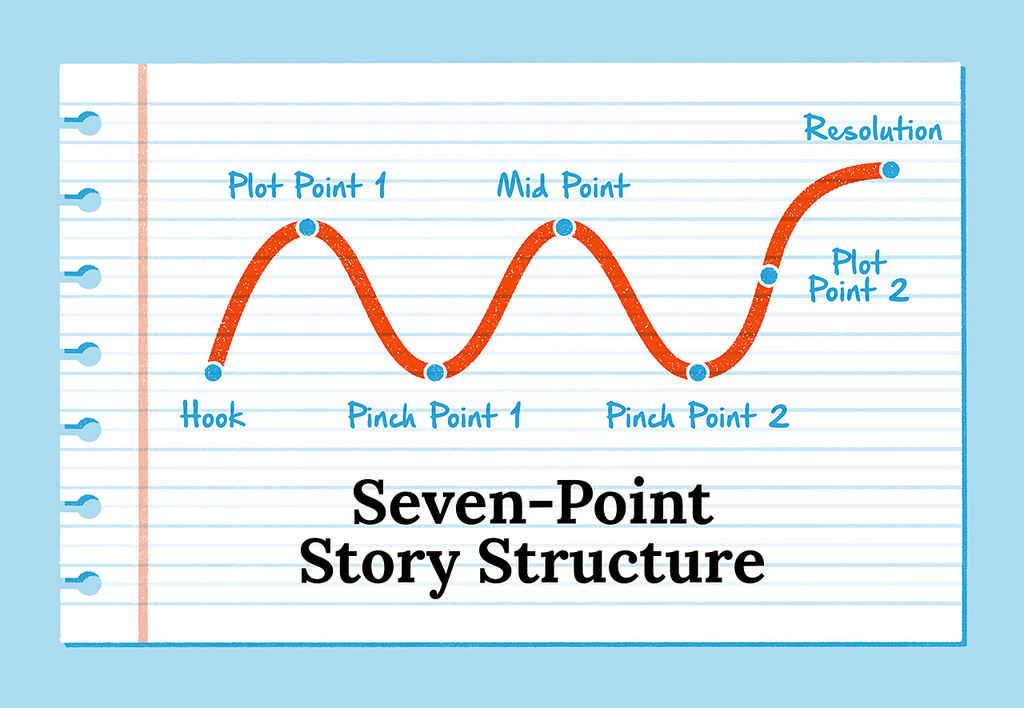

But first, let's look at the seven points in Wells's structure:

- The Hook: a compelling introduction to the story’s intriguing world and/or characters

- Plot Turn 1: an inciting incident that brings the protagonist into an adventure

- Pinch 1: the stakes are raised with the introduction of the antagonist or the major conflict or challenge

- Midpoint: a turning point in the story where the protagonist goes from reaction to action

- Pinch 2: the major conflict takes a turn for the worse, and all appears lost for the protagonist

- Plot Turn 2: the protagonist discovers something that helps them resolve the major conflict or defeat the antagonist

- Resolution: the major conflict is resolved, and the antagonist is defeated

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This may sound a bit similar to the three-act structure — both have the elements needed to construct a plot with heightening stakes leading up to a resolution. As such, the seven-point structure itself isn’t revolutionary. But what makes it so popular among writers is the way that Wells used it. The seven plot points can be approached in an almost symmetrical manner that could turn an intriguing idea into a full-fledged story — and here’s how.

How to use the Seven-Point Structure

With this structuring method, all you really need is a character and some fragments of an interesting world in mind before you dive in. For instance, as Hunger Games author Suzanne Collins has said, the idea of having teenagers fight for their lives in a reality TV show came to her when she was channel-surfing.

Q: How can writers incorporate popular story models like The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat while maintaining originality and creativity in their writing?

Suggested answer

Saving the cat can come into play in many forms. At the end of the day, readers want to root for likable heroes. If you make your main character sympathetic in some way, that sort of ticks the "saving the cat" box off nicely.

A journey can comprise so many forms. It can be a literal journey Dorothy takes from Kansas to Oz and then back again in The Wizard of Oz, or it can be an inner journey of deciding to take charge of his life and not let others make his decisions for him, as we see with Macon Leary in the book The Accidental Tourist.

As long as your "save the cat" moment and "hero's journey" uses unique ideas that have not become cliché, you should be fine.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

While we're pretty sure Collins didn't use this method to outline her hit novel, we will apply the seven-point structure to her story and show how someone with her initial idea can develop a satisfying story.

Before we dive any deeper, here’s the premise of The Hunger Games:

In a dystopian future, America is turned into a 13-district state with an authoritarian government based in the Capitol. Each year, this central government selects two “tributes” from each of the districts to participate in the Hunger Games, a nationally televised competition where they will fight each other to the death.

This is the initial idea that we will be spinning into a story using Wells’s structure — which we'll tackle in five steps.

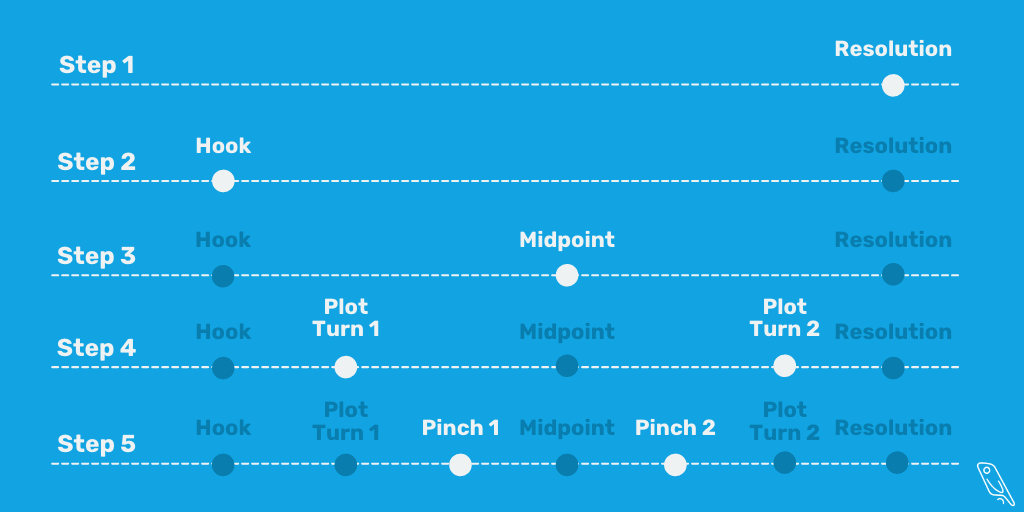

Step 1. Decide on your Resolution first

When planning a novel, it’s often advised to start at the end. By first determining your story's resolution — where everything is headed — you will always have a sense of direction throughout your outlining and writing process.

The Resolution could be the end of a narrative arc: where the story’s main problem is solved. It could also be the final stage of your protagonist’s character arc, where they become a changed person (for better or for worse). In reaching this point, the reader will have invested a lot in your story, so they would want a satisfying payoff for everything the characters have gone through. This would most likely be linked to your premise.

FREE OUTLINING APP

Reedsy Studio

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

📚 The Hunger Games: Our protagonist wins the Hunger Games.

If we start with the idea of a deadly competition, then the logical end comes when this contest ends. Our main character can be a loser or a winner in the game — though readers of most genres will prefer to see the character emerge victoriously.

You can also add consequences to their success. Winning a reality TV show like that would undoubtedly make the victor a bit of a celebrity, which may mean that their life may improve financially or gain some level of power by the end of the story.

Step 2. Create a Hook that juxtaposes with the ending

With your Resolution in mind, you can now circle back to the beginning of the story. Something helpful to do, especially if you really want to create a strong arc, is juxtaposing the start of the story with its end. Wherever the protagonist ends up, you can have them start in the opposite position. This gives the story a promise of transformation that is often satisfying to readers (think of your classic "rags-to-riches" stories).

You’ll want to think also about how to convince your readers to keep reading, given this initial condition — it’s called a hook for a reason! Luckily, you won’t have to nail it in a single short and smart sentence like when you’re writing a blurb. Still, your opening chapters must intrigue the readers, perhaps with a nuanced round character or a riveting world.

Q: What makes a compelling first chapter in a novel?

Suggested answer

The first chapter of any novel is so, so important. It's where the story is set up so that readers can get a taste of what they're in for over the next 8-12 hours. However, there is a multitude of elements that go into successful first chapters, and they must be expertly woven together to make it compelling. By the end of the first chapter, it comes down to one thing: if the reader isn't hooked, they likely won't continue. And they need three things to keep them interested.

- Curiosity

- Tension

- Emotion

The sooner these things become apparent in the pages, the better. Readers want to feel emotionally connected to the main character so that they can empathize with them, feel like they intimately know them, and root for them to reach their goal. They want to care about what happens to them. If there's tension, readers will worry about them and be curious about how it's going to play out. And when readers are curious, that means they're theorizing about what might happen. If they're theorizing, they're engaged in the story. Their brains feel like they're actively participating in figuring things out--and that's what makes them feel compelled to keep turning those pages.

My favourite novels aren't the ones that open with a beautiful sunrise or a description of the surroundings or backstory or having a character wake up. These are cliché in today's publishing landscape. Instead, they have opening lines or paragraphs that evoke such strong curiosity in me, something shocking or surprising or unexpected, that I'm hooked right from the start. These are the novels that hold my attention not just through the first chapter, but through all of them. The authors make sure there's curiosity, tension, and emotion present, along with other elements, such as a hint about the protagonist's internal conflict and flaws, an idea about goals and stakes, their desires, an imbalance of power, more showing than telling, etc. that contribute to my brain's need to feel engaged and interested.

So, it's not just about having all the elements that go into writing an exceptional novel. It's the art of weaving them all together in a style and voice that's intriguing and engaging from the very first page. Readers of fiction want to be entertained, so it's your job as the writer to make that promise and follow through with it by capturing their attention as soon as possible in the first chapter and not letting go until the very last page.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Starting with a strong opening line that is intriguing will help pull the reader into the narrative.

"Where is Papa going with that axe?" is the opening line of Charlotte's Web. We open with intrigue, and in the middle of the action of the story.

Then you want to have a strong build-up to the inciting incident, which should come at about 12,00-13,000 words into the story.

You want your main character to be likable and interesting to the reader.

You want to leave any backstory details for later on and keep the action of your opening scene continuous and going strong.

Then, if possible, you want to end this chapter with the promise of more "trouble" to come or an unanswered question regarding the trouble at hand, or at the very least, some ruffled feathers regarding your main character. There needs to be trouble brewing soon, and discomfort felt by your hero.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

📚 The Hunger Games: A resourceful teen struggles to care for her mother and sister in the poorest district of a dystopian America.

Contrasting the win and potential stardom, the protagonist can have a simple — if not miserable — start. We want someone who’s not well off, with little to no political influence, but who also has what it takes to survive. Perhaps a young adult from one of the most deprived districts of our world. Let’s call her Katniss (as she is in the final novel).

We want to give her some survival skills — so winning the game doesn't seem like a fluke. She can hunt animals and know how to barter and make deals. She also has to care about something enough to want to survive the Games — her family, for instance.

So as we’re juxtaposing the beginning with the ending, we’re also creating a nuanced character that readers would be interested in while leaving out some storytelling “tools” (i.e., Katniss’s relationships with her family) that we can use to advance the story to its resolution.

Step 3. Break the story into two with the Midpoint

To strengthen the skeleton of your story and add some complexity, decide on a Midpoint. In this particular structure, the midpoint is an event that splits your story into two parts:

- The main character reacts to the environment around them; and

- The main character proactively works towards their own goal.

Usually, this turning point comes with a trigger — an event that could spur the protagonist to set a new goal for themselves. This is commonly a 'false victory' in which the character 'wins' something (perhaps the thing that they thought they wanted) but gaining it comes at a great cost.

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy finally reaches the Emerald City (victory), but the Wizard demands that she defeat the witch (cost).

In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker rescues Leia from the Death Star (victory), but as a result, his mentor is killed, and the Empire discovers the rebel base (cost).

In response to the midpoint event, the character starts to feel the need to do something rather than be told by others what their mission or destiny is.

📚 The Hunger Games: The protagonist stops following the script laid out by the antagonists and starts to write her own story.

At the beginning, Katniss will be coerced into the Hunger Games (we can figure this detail out later). We know that she comes out of it alive at the end. How can we add an element of agency to her victory?

Let's say we have her defy the “sole survivor” rule of the Games, and she needs to emerge having saved another life. This way, our Midpoint can be when she decides that she won’t play by the Capitol rules anymore and will team up with someone else.

Note how we can go back and adjust the Resolution. Now we’re deciding to have two survivors, instead of one. As you develop more of the story, you get a better sense of the themes of your story. Consequently, you’ll find better plot developments to help unpick those themes.

Now, what could make her do this in a world where the cruelty of the system has long been accepted as the status quo? Remember that this is all about internal motivation, so let’s look back at the character we created in the Hook:

Katniss is characterized by her love for her mother and sister.

This can be the root of her motivation. If she sees that something as horrible as this contest can be imposed on someone like her sister, she may decide to topple the system. So with, say, the death of the young and innocent Tribute that she befriends in the Games — a girl that reminds her of her sister — Katniss begins to rebel against the machine.

Step 4(a). Get the ball rolling with Plot Turn 1

Now that we’ve built a loose skeleton (made out of three bones) let’s get to the meat of the story! We can start by building a bridge between the Hook and the Midpoint.

Q: What is the difference between “story” and “plot” in narrative craft?

Suggested answer

Story is a description of a connected series of events, with a clear beginning, middle and ending, while plot is the organization of those events – how we get from beginning to middle to end. So, for example, you might have a plot where events are ordered chronologically or where you move back and forth in time, or there could even be different threads within your manuscript.

To create an exciting and enthralling story, where readers will feel compelled to turn the page to find out what happens next, think about change and conflict. These should drive events and motivate your characters until the story reaches a satisfying conclusion. What conflicts or challenges do your characters face as the story progresses? How do these characters develop?

To create a successful plot, carefully think about organizing the events in a way that feels effective and purposeful. What are the best places to start and finish? Are there enough 'hooks' to keep readers engaged? Is the tension building up before a final resolution? Sitting down and plotting out before putting pen to paper (or opening up that blank document!) can really help you ensure that you are hitting that beginning, middle and ending in a satisfying way that will sustain your readers' curiosity and engagement with your writing.

Jenna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Plot is what actually happens in the book. The sequence of events that takes place. While the story is more about the reasons behind what happens. Why does your main character want what she wants? What is she feeling and thinking at any given point? What do characters feel about each other and why? Story dives a bit deeper into the heart of the book, and not just the events that transpire. Strong books have both a strong plot and a strong story to them.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The Hook establishes the 'ordinary world' of the story, so this bridge must have something to push the protagonist out of this stable situation. In other words, there should be a slight turn in the course of the story to get things moving, like an inciting incident or a call to adventure (like in the Hero’s Journey, also known as the monomyth) — an occurrence that the character has to respond to. It could be a quest, a prophecy, the loss of a job.

We've established that the protagonist is reactive in the first half of the story, but they still have to be decision-makers. They may not be proactive yet, but they can’t be passive either.

You might find it helpful to answer questions like:

- What happened to disrupt the status quo of the Hook?

- Why must the protagonist respond to this stimulus?

- What’s at stake for the protagonist, given the circumstances?

📚 The Hunger Games: To save her sister, our hero volunteers to take her place in the contest.

So we want to get Katniss into the Games. A random selection mechanism could easily do the trick — Katniss's name could just be plucked out from a hat — but it wouldn’t feel as though Katniss was compelled to go. Instead, by letting Katniss’s sister be the one selected, the stakes are raised for our family-oriented protagonist. There is only one logical step for her to take next, given everything we know about her character so far: she needs to volunteer to take her sister’s place. She makes the only decisions her circumstances and personality will allow her to make.

So we want to get Katniss into the Games. A random selection mechanism could easily do the trick — Katniss's name could just be plucked out from a hat — but it wouldn’t feel as though Katniss was compelled to go. Instead, by letting Katniss’s sister be the one selected, the stakes are raised for our family-oriented protagonist. There is only one logical step for her to take next, given everything we know about her character so far: she needs to volunteer to take her sister’s place. She makes the only decisions her circumstances and personality will allow her to make.

Need help plotting your book? Meet the editors who can help you map out your story.

Hire an expert

Helen L.

Available to hire

Literary Agent and Developmental Editor. I represent incredible authors at Ki Agency. My editorial focus is on Fantasy, Sci Fi and Romance.

Chris U.

Available to hire

I am an expert in genre fiction, with years of experience evaluating short fiction. I want your wildest stories to find a published home.

Laura S.

Available to hire

Editor and published author (Penguin Random House, Simon and Schuster) with over a decade of experience. Expert in novel and query edits.

Step 4(b). Use Plot Turn 2 as a final push

To continue with this symmetrical method that we’ve been working on so far, we can now go to Plot Turn 2. This is another “turn” in the story, where things begin to head toward its ending. Ideally, this action would take place after the Midpoint and solve the story's main conflict, bringing us to the finish line.

This point usually contrasts with Plot Turn 1 because it is the pinnacle of the character’s agency. Instead of being compelled to do something, they actively choose to use all the “tools” they have gathered to finally achieve that new goal that they created for themselves at the Midpoint. They start to create their own circumstances.

📚 The Hunger Games: Katniss outsmarts the Gamemakers by denying them the finale that they need.

At the Midpoint, Katniss decides to survive the game with another tribute to defy the Capitol. Naturally, the powers that be do not allow that and insist that one of them kill the other. But rather than let that dictate her decisions, we can have Katniss use her knowledge of the wild and her understanding of the contest’s television appeal to subvert the game and refuse manipulation.

Perhaps she suggests that she and her fellow tribute abandon the rule book and kill themselves, threatening the authoritarian government with a victor-less game. To keep the audience happy, the Capitol must concede, and our hero achieves her goal.

Step 5(a). Add some pressure at Pinch 1

We now have a rough story: a status quo, a call to adventure, an epiphany, the ultimate action, and the resolution. We are missing pressure points — moments that join the different parts while also increasing tension to make the story more gripping. This is where the Pinches come in.

After Plot Turn 1, where the character has just been pushed into an adventure, things should become more exciting. So how can you do this?

You can introduce the antagonist at Pinch 1 and show the readers just how challenging the route ahead will be for the protagonist. The antagonist should also represent the major conflict, the essential but sometimes underlying issue that the protagonist will choose to tackle at the Midpoint.

📚 The Hunger Games: Our protagonist meets other contestants and the showrunners.

Sure, one may argue that the fact that Katniss is entering a deadly contest is pressure enough. But we want readers to be on the edge of the seat! So we can create an event before the Games, like a training session, in which Katniss meets the other tributes, most of whom are intimidatingly prepared for this bloodbath. It’s looking more and more unlikely that she’ll get out of this alive.

Q: What is the 'saggy middle' in storytelling, and how do I fix it?

Suggested answer

A 'saggy middle' occurs when a story loses momentum, tension, and trajectory right around the midpoint of the story. A story can lose it's steam (and with it, a reader's interest) when character arcs stall, plots become muddled and messy, and subplots abound with no sense of direction. Stories can also sag if they fill pages with descriptive information that does little to engage the characters or further the story arc.

But never fear! This is a very fixable problem. First, think about the ideas at the heart of your story. What story do you want to tell? What lies at its core?

With that in mind, review the midsection of your story with an eye to the issues described above. Once you identify your problem areas, you can set about rewriting with a goal of increasing the tension by increasing the stakes for your characters, adding new conflicts/problems for characters to explore, cutting excess descriptions and sections that over-explain character motivations/backgrounds/actions, and tightening sections that do little to further the core plot that drives the story.

Erin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I tend to see saggy middles show up when authors are adhereing to a strick timeline of events, rather than sharing scenes that pull the plot forward. For example, I edit a lot of middle grade fiction and a saggy middle might include multiple chapters that open with the protagonist waking up and close with the protagonist going to bed. Or going to school, then getting home after. Readers don't need the day-by-day minutia to get from one scene to the next.

Instead, focus on what will pull your plot forward, and think of your middle as scenes rather than a timeline that gets you from point A to point B.

I usually suggest that authors step away from the manuscript and instead write scenes, even if out of order, that they need for their story to make sense. When finished, they can line them up in order, and then fill in the blanks for a much faster-paced and cohesive middle. Even if you don't have a saggy middle, this is an effective practice for planning and plotting purposes.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The 'saggy middle' of a story is the part of the story where the inciting incident - or the problem in the story - has already happened, but the ending, or climax and resolution, is nowhere in sight. It really does fall in the middle of the story.

There are several ways to handle this issue:

*Use a subplot with the main character or a secondary character that will still need its own resolution and will bring in another layer of trouble for your character[s]. In The Wizard of Oz, each of Dorothy's three friends suddenly has their own problems. The scarecrow loses his stuffing, for instance, so the storyline shifts for a bit from Dorothy's desire to get back to Kansas - her hero's journey and the through line of the book - and takes a slight turn to focus on the scarecrow and friends before turning back to Dorothy's main plot line again of getting home.

*Raise the stakes - create even more trouble for your character and/or make the result[s] of the trouble even more dire. In the book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, first, Mrs. Morris the cat is sent to the hospital, then humans that are Harry's friends, then finally, Ginny is in trouble, who will end up being Harry's love interest. So the stakes and problems keep building all the way through the book until the final climactic scene.

*Use what is called a 'midpoint reversal': This is where the character changes his mind about the issue and is not opposed to it any longer. In the movie "Tootsie", at first, Michael does not want to pretend to be a woman to get work, but by the middle, he loves the idea of pretending to be a woman and wants to take things even further, which causes friction between Michael and his agent. So more trouble occurs because of this mindset reversal, which then leads the book to its satisfying conclusion.

You don't have to use all of these techniques, but try one out in the middle of your book, and see which one works best for your own story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

We can also introduce the people who design the Games. They will be the ultimate antagonist (even though the readers might not know that yet) since we decided that at Midpoint, Katniss will start rebelling against the rules they create. We can even drop hints about how beholden the showrunners are to the audience, which Katniss witnesses without connecting the dots and realizing that she can use it to her advantage — after all, she’s still in the 'reactive' portion of the story!

Step 5(b). Kill all hope with Pinch 2

Finally, we have the last pressure point. Our protagonist has chosen to do something about their situation, and we know that they’re getting there at the end. However, just because they’ve set out on a quest doesn’t mean that it’ll come easy. Setting obstacles for the protagonist makes the end that much more satisfying to reach, and it tests your character. This is important even when you’re not basing your story as much on the character arc as the narrative arc, as challenges can also show how your character stays true to their values.

As such, try to take away all hope at this point. This is an “all is lost” moment where, despite having found the true antagonist of the story, the protagonist feels as if they can’t do anything about it. In a way, because of this devastating moment, the protagonist is encouraged to think outside the box, to reassess their skills, and to find the way out of their predicament the way they do in Plot Turn 2.

📚 The Hunger Games: The antagonist tricks our hero, and it seems like all is lost.

Katniss is rebelling against the system and working with her fellow Tribute to survive this together — what can the Capitol do to take away all of her hope? How about this: they can pretend to let her have it, i.e., change the rule so that it seems like they will allow two winners. And then, at the crucial moment when there are only the two final Tributes left, they can take it all away and force one of them to kill the other. This way, the government's absolute power and their love for dramatic TV can both be reaffirmed.

Q: What strategies make a redemption arc feel earned, credible, and emotionally powerful?

Suggested answer

I'd say the main thing here is to stay true to the character. The redemption has to feel authentic based on how the character's been presented thus far in the book/story. Keep in mind the character's past actions and reactions as a whole. Because in the end, if the redemption feels like it's been shoehorned in or has come out of left field, the reader will feel that. However they redeem themselves, it has to feel like something that specific character would do—not just any character who's gone through the things they've gone through, but that character in particular. As for impact, the more three-dimensional the character is, the stronger the impact will be when their redemption comes about, so making sure they have a well-rounded, more-than-surface-level personality is absolutely key.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Just as in real life, sometimes people have to hit rock bottom before they change and accept that they are an addict or an alcoholic, etc. So if possible, you want to show this character having some sort of reason to see that they need to change. Perhaps their negative actions have impacted someone dear to them, and they feel regret or remorse, which then motivates them and serves as a catalyst for change.

There should always be reasons why characters act the way they do, whether positively or negatively, and a sort of "awakening" might be a good idea if they must change their stripes for this change to feel organic and not forced.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

And with that, we’ve constructed a plot for the story. Let’s reorganize it in chronological order.

- Hook: Katniss lives in a small, poor house with her family.

- Plot Turn 1: She is compelled into volunteering for the Hunger Games to save her sister.

- Pinch 1: She meets her opponents and the showrunners before the Games begins.

- Midpoint: A bit into the Games, Katniss’s young tribute friend is killed, and our hero chooses to stop playing by the rules. She wants to survive, together with another friend.

- Pinch 2: Katniss hits rock bottom when she finds out that the Capitol has tricked her into believing that they would agree to have two victors.

- Plot Turn 2: Using her wiles, Katniss and her friend outsmart the showrunners by threatening no victors at all.

- Resolution: The showrunners give in, and she emerges victorious with her fellow Tribute. She goes home to a big new house for her family.

Why should you use the Seven-Point structure?

The process that we just went through showed you how the seven-point structure can be used to carefully construct a plot for your story idea. By bouncing back and forth between the points, you can figure out details in the narrative that you can string together into a logical flow (great if you want to use narrative principles such as Chekhov’s Gun, for instance). This system is best for authors who:

- Have an interesting character or world, but not yet a story;

- Want to create a compelling and coherent narrative or character arc;

- Are looking for a thought process that helps spin out a plot.

Most stories aim to do the same thing at the end of the day: to pose a problem and have interesting characters solve it (or at least try to) despite all the challenges they face. A story structure is ultimately a tool for authors to visualize and plan their own story, and this is where the seven-point structure can come in handy.