Guides • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Oct 13, 2023

12 Elements of Poetry Every Poet Needs to Know

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Much like any other type of literature, poetry can be broken down into various different devices. Rhyme is the most well-known, but there are dozens of elements that can be used to construct a poem. While poets may employ many of these devices subconsciously (having long since added them to their toolkit), most of them will be able to identify these elements and understand how they help their craft.

In this post, let’s explore 12 of the most common poetic devices and what they add to a poem.

1. Rhyme and rhyme scheme

When we think of poetry, rhyme is probably the first poetic device that comes to mind. From the tales of Mother Goose to the works of the greats, it’s one of the defining characteristics of poetry. Modern poets may not use rhyme as often as their predecessors, but it remains an important part of what makes poetry poetry.

FREE RESOURCE

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

What is rhyme in poetry?

It’s the repetition of syllables or similar sounds, typically at the end of a verse. A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes in a poem or, in other words, which lines rhyme with each other.

Some common rhyme schemes you might see are AAAA, ABAB, ABBA, where two matching letters indicate that those lines rhyme with each other. However, there are many more to be found among the different forms and structures of poetry.

There are also many different ways in which two words might rhyme. While everyone can detect a full rhyme (e.g., might and light), you might also find half rhymes or slant rhymes (e.g., bog and bug) that sound just enough like one another to work.

There’s also a range of places where you can rhyme within lines or stanzas. End rhyme — the rhyming of the last syllables in two or more lines — is the most common. But there’s also internal rhyme, which occurs when two or more words rhyme within a singular line (e.g., there’s double trouble at the Hubble lab).

Example: “Neither Out Far Nor In Deep” by Robert Frost

Robert Frost’s poem follows a simple ABAB rhyme scheme (italics and bold text added for emphasis).

The people along the sand

All turn and look one way.

They turn their back on the land.

They look at the sea all day.

Of course, a collection of rhymes does not a poem make. While some poems don’t use any rhyme at all, almost every piece of verse has a keen sense of rhythm.

2. Meter

Meter is the basic structure of a line of poetry, whereby stressed and unstressed syllables are used in a predetermined way to create rhythm. In a sense, it’s the heartbeat of a poem.

How is meter created?

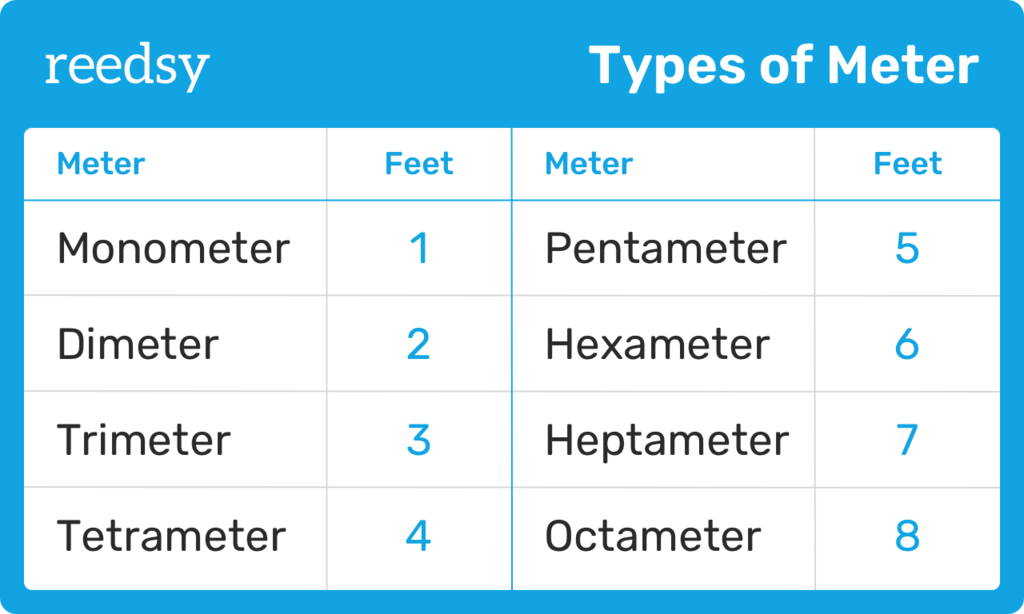

When considering a poem’s rhythm, you can break a line of poetry into multiple “feet.” These are individual units within a line that have a specific number of syllables with specific emphasis placed on those syllables.

Metrical feet are usually only two or three syllables long. One of the most common kinds of feet in English is an iamb, which consists of two syllables: one stressed and one unstressed. For example, you would always stress the first syllable of the word “poem” but never the second. (Only a maniac would pronounce it “po-EM” instead of “PO-em.”)

Each line has a set number of feet. For example, in iambic pentameter, which we often see in Shakespeare’s works, there are five iambs per line — this gives us a total of ten syllables per line (e.g., “Against my love shall be as I am now”).

There are many different types of feet and meters that you can mix and match to create rhythm. Some regularly used ones include iambic pentameter, trochaic octameter, and anapestic tetrameter. Below, you'll find examples of the most common types of poetic feet.

| Syllables | Stress | Example | |

| Iamb | 2 | down UP | I wandered lonely as a cloud |

| Trochee | 2 | UP down | Double, double toil and trouble |

| Spondee | 2 | UP UP | Bang bang! |

| Dactyl | 3 | Up down down | Just for a handful of silver he left us |

| Anapest | 3 | down down UP | The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold |

Example: “Sonnet 18” by William Shakespeare

Who better to demonstrate the uses of meter than Shakespeare himself? His sonnets are arguably the popular examples of iambic pentameter in the English language.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand'rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow'st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Notice how the number of syllables in each line remains consistent, creating a regular beat that propels the sonnet forward. You might also detect that the flow of the words builds up in the first line, then falls in the second line — a pattern that repeats throughout the piece, creating a sense of ebb and flow. That’s iambic pentameter in action.

In Shakespeare’s plays, he often switches between using iambic pentameter and a more prosaic style. In a very similar way, not all forms of poetry require a standard use of meter.

3. Lineation

Also known as layout, lineation is about how words and sentences are physically arranged on the page. While poetry is often best enjoyed when spoken aloud, it can also be a visual medium — and lineation is a large part of that. How a poet decides to break up a sentence on the page can create pauses that alter its mood, meaning, or rhythm.

With certain forms like concrete poetry, poets may take full advantage of this visual aspect and arrange the lines in such a way that they form an image on the page.

Example: “Crepuscule” by E.E. Cummings

E.E. Cummings was well-known for experimenting with different elements of poetry, including lineation. In this piece from 1917, he conjured up an image of twilight that jars the reader with its unusual line breaks.

I will wade out

till my thighs are steeped in burn-

ing flowers

I will take the sun in my mouth

and leap into the ripe air

Alive

with closed eyes

to dash against darkness

in the sleeping curves of my

body

Shall enter fingers of smooth mastery

with chasteness of sea-girls

Will I complete the mystery

of my flesh

I will rise

After a thousand years

lipping

flowers

And set my teeth in the silver of the moon

Here, Cummings breaks up the verses and arranges them on the page so that certain words and phrases stand out, like “alive.” The pauses these breaks create add a specific rhythm that would be difficult to achieve with regular enjambment.

4. Form

Pulling back for a second, let’s take a wider look at poetry in general and talk about form. Form is the actual structure of a poem and consists of three parts: rhyme scheme, meter, and lineation.

As previously mentioned, rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes while meter is about the use of stressed and unstressed syllables. Meanwhile, lineation refers to the way line breaks and stanzas are arranged — how many lines there are per stanza, for example. Taken together, the variations of these three elements lead to many types of poetry forms, from odes and ballads to villanelles and limericks.

Each form of poetry has its own specific lineation, rhyme scheme, and meter as part of its structure. A sonnet wouldn’t be a sonnet if it wasn’t written in iambic pentameter, nor would a haiku be a haiku if it didn’t follow the 5-7-5 syllable structure. Form makes a poem recognizable, and poets can use rhythms to elicit a particular emotion or reaction from their readers. Certain structures also lend themselves well to particular topics — the ode and the elegy, for example, praise and eulogize their subjects, respectively.

While all the rules imposed by poetic forms might make poetry seem restrictive, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Many modern poets write in free verse, constructing their own meters and rhyme schemes. Many don’t rhyme at all, relying purely on meter and lineation. Once you know what the rules are, you can break them to make something entirely new.

Example: “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats

Based on his observations of ancient artifacts he saw at the British Museum, John Keats wrote this poem, dispensing with the odes made popular by Horace and Pindar in favor of a form he developed himself. Keats starts describing a particular Grecian urn with a quatrain (four lines with an ABAB rhyme scheme) that leads to a sestet (six lines with a CDECDE rhyme scheme). Each line of Keats’ poem is rendered in iambic pentameter. The following is the poem’s first stanza:

Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring'd legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

While form is a foundational part of poetry, don’t let it be a constraint. Like Keats, you don’t have to stick to tradition and can always make up your own form to suit your needs. If you find certain forms too restrictive or can’t get your rhyme scheme to work, always feel free to experiment.

Now that we have some of the basics down, let's look at some other elements poets take into consideration when creating new works.

5. Point of View

Much like in prose, poems are also told from a specific point of view. In other words, who is the speaker of the poem? Is it the poet themselves, a character, or an omniscient narrator? Is the poem written in first, second, or third person?

Who tells the story is just as important as how it's told. No two people have the same outlook, so a poem’s point of view will affect its overall meaning. If an old woman and a young boy examined the same event, emotion, or theme, they would likely come to a different conclusion.

Example: “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley uses an interesting framing device for this poem, where the bulk is told from the viewpoint of a traveler the narrator once met.

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Rather than telling us about the statue himself, Shelley writes about a story a traveler once told him — or, more likely, a fictional narrator. This story within a story further removes us from this “King of Kings,” reminding us that even the greatest deeds eventually become half-forgotten tales. And this, of course, is the central theme of the poem.

6. Theme

Speaking of themes, you can’t have a poem without one! Whether you’re writing about what you had for breakfast or the love of your life, poetry thrives on deeper meaning. In other words, a poem’s theme is the message it’s trying to get across.

Poetry can be about anything: love, death, war, aging, growing up, nature, justice, and so much more. Any possible human experience you can think of has probably been written about in poetic form — even if that experience is just one’s love for breakfast food.

Example: “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” by Emily Dickinson

Not all poems state their meaning so obviously, but this one by Emily Dickinson states its theme in its opening line. Many poets and scholars consider it to be a powerful poem about life due to how Dickinson describes hope in it.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me.

Dickinson uses an extended metaphor — that of hope as a feather — to underscore her theme. As the poem progresses, we see the many different faces of hope. By the end, we can imagine hope as a creature that is both delicate and robust, confident and constantly besieged. It’s an incredible metaphor that’s hard to shake once you’ve encountered it — and speaking of metaphors….

7. Metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech in which two objects or ideas are compared without using “like” or “as” — and relating them directly to each other instead. For example, “hope is a thing with feathers” as opposed to “hope is like a thing with feathers.”

This poetic Swiss Army Knife can be found in just about every corner of the poetry world and can serve many purposes. A good metaphor shows (not tells) an idea without having to explicitly spell it out — plus, it creates imagery and action in the reader’s mind, adding to the mood or atmosphere of a piece. It's also efficient: you could spend pages describing isolation and sadness, or you could find the perfect metaphor like Carson McCullers did for the title of her debut novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

Example: “Heart” by Dorianne Laux

Speaking of hearts, poets such as Dorianne Laux have imagined the heart as a shapeshifter that morphs to encompass the many emotions a person can experience. Take a look at the following excerpt of her poem, “Heart”:

The heart shifts shape of its own accord—

from bird to ax, from pinwheel

to budded branch. It rolls over in the chest,

a brown bear groggy with winter, skips

like a child at the fair, stopping in the shade

of the fireworks booth, the fat lady's tent,

the corn dog stand. Or the heart

is an empty room where the ghosts of the dead

wait, paging through magazines, licking

their skinless thumbs. One gets up, walks

through a door into a maze of hallways.

Behind one door a roomful of orchids,

behind another, the smell of burned toast.

The rooms go on and on: sewing room

with its squeaky treadle, its bright needles,

room full of file cabinets and torn curtains,

room buzzing with a thousand black flies.

The dizzying amount of imagery in this poem underscores just how changeable a heart, and a person’s emotions, can be. The shift from joyous images of children and birds to the darkness of ghosts and flies allows the reader to experience different moods without ever being told outright what emotions to feel.

A well-used metaphor will often be repeated throughout a poem, and as we’ll soon discover, repetition is a technique that will pop up time and again in many different ways.

8. Alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of a consonant sound at the beginning of several words (e.g., Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers). Remember that this literary device is about the repetition of a specific sound, so watch out — just because two words might start with the same letter doesn't mean they’re alliterative.

A carefully crafted alliterative phrase can affect the beat or rhythm of a poem, slowing its pace down as the reader carefully navigates any tricky repeating consonants.

Example: “The Tyger” by William Blake

Blake’s oft-quoted poem opens with a verse brimming with alliteration (bold type added for emphasis):

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

The repetition here evokes the feeling of a chant, setting the tone for the rest of the piece as the poet regards his subject with the awe and reverence usually reserved for the sublime.

9. Assonance

Remember how we said that rhymes can occur within a line as well as between them? Assonance is a close cousin of those rhymes, where vowel sounds are repeated within a line of poetry. Although it’s often called a rhyme, assonance is more similar to alliteration since it’s about the repetition of a specific sound. The words in a line must be located fairly close together for the repetition of vowels to count as assonance (e.g., The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain).

Often, assonance is used to invoke a specific mood as specific kinds of vowel sounds can affect how we perceive a poem’s tone. For example, you’ll typically find long vowel sounds in more serious pieces as they slow down the poem, making it more somber.

Example: “The Bells” by Edgar Allan Poe

Poe opens the second stanza of “The Bells” with a few lines of assonance, using it to set the tone.

Hear the mellow wedding bells,

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight!

From the molten-golden notes,

And all in tune,

What a liquid ditty floats

To the turtle-dove that listens, while she gloats

On the moon!

Pay attention to the assonance here in the short “e” sounds in “mellow wedding bells.” This gives the beginning of the stanza a light, joyous tone, before shifting to something darker later on in the poem, where you’ll start to see the repetition of longer vowel sounds.

10. Tone

Tone, which is also known as the “mood” of a poem, refers to the poet's attitude toward their subject. Just like human emotions, poems can be happy, sad, regretful, nostalgic, angry, and so much more. How tone is expressed in a poem is varied and depends on the wants of the poet. Elements like rhyme, figurative language, meter, and syntax, just to name a few, can all be used to create a specific tone.

Example: “A Birthday” by Christina Rossetti

Through repetition and the inclusion of pastoral images, Christina Rossetti creates a joyful tone in this love poem.

My heart is like a singing bird

Whose nest is in a water'd shoot;

My heart is like an apple-tree

Whose boughs are bent with thickset fruit;

My heart is like a rainbow shell

That paddles in a halcyon sea;

My heart is gladder than all these

Because my love is come to me.

Raise me a dais of silk and down;

Hang it with vair and purple dyes;

Carve it in doves and pomegranates,

And peacocks with a hundred eyes;

Work it in gold and silver grapes,

In leaves and silver fleurs-de-lys;

Because the birthday of my life

Is come, my love is come to me.

Images of rainbow shells, singing birds, and endless bounties underscore the narrator’s happiness and excitement now that their love has come to them. Specifically, the way nature is invoked — full of action, not just description — makes it feel like something new and wonderful is blossoming, which adds to the sense that the narrator is professing their love from a mountaintop (or somewhere less clichéd).

11. Enjambment

You’ve probably noticed that poetry doesn’t strictly follow the rules of grammar. Sometimes, a sentence will continue past the end of a line without any punctuation marks. This is known

as enjambment.

This changes how we would naturally read a line, allowing the poet to manipulate rhythm. Sometimes, enjambment can be used to create emphasis or drama — cutting off a thought in a strategic place. These pauses and moments of silence might otherwise be difficult to achieve with standard punctuation, so think of enjambment as the poet’s secret semicolon.

Example: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

This classic example of enjambment is short but impactful. Gwendolyn Brooks uses it both to create rhythm and emphasize her point.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

The enjambment after each “We” creates a pause that puts emphasis on the first words of the next line, suggesting that the narrator is hesitating or perhaps coming up with the next words on the fly. The pauses also create a syncopated rhythm, giving the piece an unusual musicality.

12. Consonance

Similar to assonance, there is also consonance. But instead of repeating vowel sounds, it’s all about the repetition of consonant sounds within a line of poetry. This can happen at the beginning, middle, or end of the words. Similar to assonance, something can be considered consonance if the repeated syllables are located fairly close to each other.

Much like the other devices we’ve examined here, consonance adds rhythm to a poem and, through the right collection of sounds, can also evoke a specific emotion.

Example: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot

The consonance in this section of T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” lends a lyrical quality that matches and accentuates the poem’s whimsical mermaid imagery.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black.

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

Note that in the final stanza, the repetition of the aspirated “w” sounds in “white,” “waves,” “wind,” and “water” mimic the rise and fall of ocean waves. And there you have it! Some of the most common elements of poetry.

With the basics down, you can do anything, including writing your own poem. Which is exactly what we'll cover in the next part of this guide.