Guides •

Posted on Nov 30, 2021

How to Write Literary Fiction in 6 Steps

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Literary fiction can be a slippery genre to write within, seeing how it avoids easy definitions. In many ways, that’s a good thing: multifaceted and expansive, it’s probably the category of books that contains the widest range of stories, and the one readers always approach with a readiness for surprise.

To make the most of writing in this fun genre, we’ve assembled 6 simple steps you can follow.

1. Start with a topic you wish to explore

The first step is simple: all you need is to identify a theme or topic that interests you. At this stage, your “topic” can be universal or very specific. There’s no need to transpose this topic into a particular character and a situation yet — just think about some of the issues that you find curious or feel strongly about. These could include aspects of the human experience or matters related to society and social structures.

To give you a few examples of some works and their overall themes:

- Motherhood — Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs, where the protagonist considers accepting a sperm donation and becoming a single mother;

- Grief — Raymond Carver’s ‘A Small, Good Thing,’ where a mother is faced with her son’s sudden unexpected death;

- Power — Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, which charts Thomas Cromwell’s rise to prominence in the Tudor times.

2. Identify the core of your theme or idea

You don’t need to have a thesis to expound upon in your story — Les Misérables would be tragically reduced if you just condensed it into “stealing is bad,” and many works of literary fiction are similarly more complex than a single statement. Ideally, though, your work will be saying something.

Take Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, for example. It tells the parallel stories of two people: one a schoolgirl in Japan, the other a Japanese-American author living in British Columbia. The story is about identity, as it shows the two characters searching for some kind of meaning in their relationships and their place in the world.

Avoid moralistic lessons

Whether you overtly show your personal beliefs to your readers or let them draw their own conclusions, it is still helpful for you as a writer to figure out how you feel about certain issues. (That may happen as you write, which is not an issue, as you can edit your work later on.) If you do have clear feelings on the subject at hand, however, be careful not to write a story that falls flat by offering a one-sided moralistic “lesson.” Instead, think about how your narrative can show the nuanced complexities of an issue. Allow contradictions to exist in your work, without worrying about teaching the reader the right way. No one likes to be patronized.

Percival Everett’s novel Erasure is really good at this: sophisticated and irreverent, it critiques the way the publishing industry stereotypes minority authors, reducing them to exoticized tropes. Instead of simply concluding that “publishing stereotypes are harmful,” the novel cleverly satirizes the public response in direct contrast with the reaction of the book’s protagonist. Everett looks at something more complicated than “publishing getting it wrong”: he points to the multi-layered alienation it results in, and the effect is that the book stays with the reader for a long time.

Percival Everett’s novel Erasure is really good at this: sophisticated and irreverent, it critiques the way the publishing industry stereotypes minority authors, reducing them to exoticized tropes. Instead of simply concluding that “publishing stereotypes are harmful,” the novel cleverly satirizes the public response in direct contrast with the reaction of the book’s protagonist. Everett looks at something more complicated than “publishing getting it wrong”: he points to the multi-layered alienation it results in, and the effect is that the book stays with the reader for a long time.

Need some more guidance? Check out our free course 'How to Craft a Killer Short Story' — it was created by Laura Mae Isaacman, an editor who has worked with Joyce Carol Oates and other luminaries of the short fiction world.

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

3. Ground your idea in a specific situation…

Your next step is to come up with a specific character in a specific situation that hinges on your central theme. Say you want to write about “the immigrant experience.” You don’t need to come up with an astonishing hot take on what it’s like to live away from home, but you can depict a specific person’s experience in a moving, relatable, or entertaining way if you just commit to some detail.

Here are a few more ideas for developing a plot based on your theme:

Conduct a fictional experiment

Because literary fiction stories are very commonly character-driven, you can use a story as a space to conduct a hypothetical experiment.

- If X and Y personalities are brought together in Z circumstances, what will happen?

- How do different characters respond to the same problem?

- How would person A react if person B acted in a certain way?

A book that does this well is Bryan Washington’s Memorial, which chronicles the changes in a romantic relationship, when one of the two young men must go to Japan to visit his ill father. The book tests their romance with a newly-created distance — tracing their shifting dynamic as they’re both forced to open themselves up in new ways.

Don’t be afraid to be weird

Literary fiction is home to a lot of very, very strange fiction, where writers can have fun and embrace bizarre ideas. When writing literary fiction, listen to any whimsical or wacky ideas that come to you, whether your protagonist develops a substance abuse relationship with lip balm, turns into a lamp, or starts to speak in ways no one understands.

One recent example of ‘weird’ literary fiction is Suyaka Murata’s Earthlings, which tells the story of Natsuki — a woman convinced she’s an alien and trying to navigate societal pressures while retaining her personal integrity. It’s an utterly bizarre story that pushes past what’s considered acceptable behavior and makes readers see the standards for “acceptability” in a new light.

4. Or filter it through a particular character’s experience

Literary fiction is usually character-driven, and characters are best explored when an event takes place and reveals the finer textures of their personality. Though stories about stasis, where nothing happens, are acceptable in literary fiction, you’ll find that events help move your story forward, and give you the trigger needed to unpack your characters.

In literary fiction that overlaps with genre fiction, these events tend towards the dramatic, like the rise of a totalitarian government (think Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale), significant historical events (Thomas Cromwell’s rise to power in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall) or fantastical elements like the widespread amnesia in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant.

In experimental, realist, or contemporary forms of literary fiction, the event can either be a small, otherwise insignificant moment, or a major life event. It all counts: an offhand comment made by a stranger, a death or birth, or an emotionally poignant moment like dropping off your child at nursery for the first time.

You don’t need a likeable protagonist

In genre fiction, the reader often roots for the main character: they want to see the unlucky-in-love writer find romance, the detective solve the crime, or the teenager to finally grow up. But flawed characters are far more common in literary fiction — where stories sometimes function as character studies trying to understand how a character has come to be a certain way, or to simply observe or satirize the breadth of human behavior.

A great example of a flawed character can be found in Eliza Clark’s Boy Parts, where Irina, an explicit photographer of random Newcastle men, falls into a self-destructive and violent spiral. She’s not a character to idolize, but one whose crazy downfall readers find compelling.

The best literary fiction editors are... on Reedsy!

Ann K.

Available to hire

Book editor and award-winning writer who works on fiction and nonfiction, with special expertise on books in translation.

Mitchell G.

Available to hire

Editor and writer with 7+ years in publishing, specializing in upmarket, literary, and contemporary fiction and non-fiction.

Allison L.

Available to hire

Detail-driven, dedicated editor (for 15+ years) with a passion for helping writers of literary fiction bring their work to the next level,

David Foster Wallace’s short story collection Brief Interviews with Hideous Men also features flawed characters: here, fictional interviews reveal the egocentric, cruel behavior of certain men. The interview format singles out their words, which would otherwise be lost in a story merging plot with dialogue.

When writing literary fiction, set yourself free from the need to create benevolent, likeable figures: saintly figures are unrealistic and basic anyway, so your readers will thank you for more nuanced characterization.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

4. Consider how you might tell your story in unexpected ways

Literary fiction is associated with unusual and interesting approaches to storytelling — fractured chronology, unusual media, strange POV choices...

Think about it this way: poets are used to paying attention to the way they present their ideas, weighing up the limitations and opportunities residing in each form — literary fiction borrows this flexibility from poetry, allowing you to be wildly experimental (or wildly traditional). Consider creative formal approaches that might help you illustrate your points: you can tell your story in future tense, in HTML, in texts, or start in medias res… As long as your story’s final form is an intentional choice and not a random afterthought, anything goes.

Don’t go crazy for no reason

Don’t go wild for the sake of it. There should always be a reason behind a strange formal choice: the form needs to tie in with the content. Consider the novel little scratch by Rebecca Watson, for example. While the story is told in experimental, stream-of-consciousness prose, the form perfectly mirrors the protagonist’s fraught emotional state after experiencing sexual assault. Without some solid reason for making such a grand stylistic choice, you run the risk of succumbing to literary fiction’s most common pitfall: pretension.

Don’t be afraid to 'steal'

There’s no such thing as plagiarism when it comes to writing techniques. Everyone’s influenced by everyone, so don’t worry so much about being unique: instead, ask yourself how you can learn from others’ approaches and how you can adapt successful techniques to improve your story. Just don’t pretend you innovated in a cultural vacuum, and acknowledge your influences when speaking about your work.

To give you an example of how you might take an idea and put your own spin on it, look at Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This. While both use fragmented, first-person vignettes — telling a succession of seemingly unrelated stories — the intended effect is very different indeed.

Bluets uses confessional vignettes to intimately portray the writer’s melancholy, whereas No One is Talking About This uses vignettes to mirror the internet’s endless feed of information. The fragmented technique they share sets both texts up with a foundation of honesty, a sense of being confided to — so if you like something that another author has done, feel free to ‘steal’ it and see how it works in a different context!

5. Remember your story structure basics

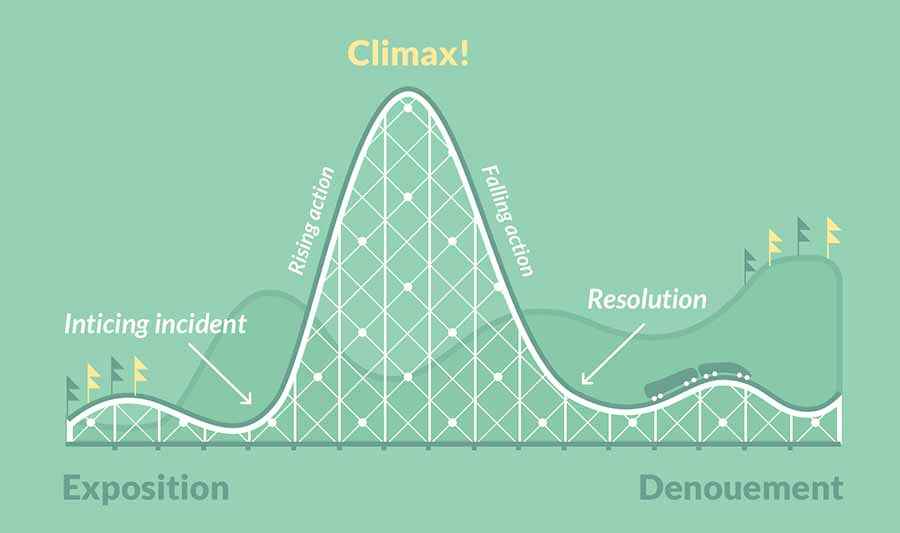

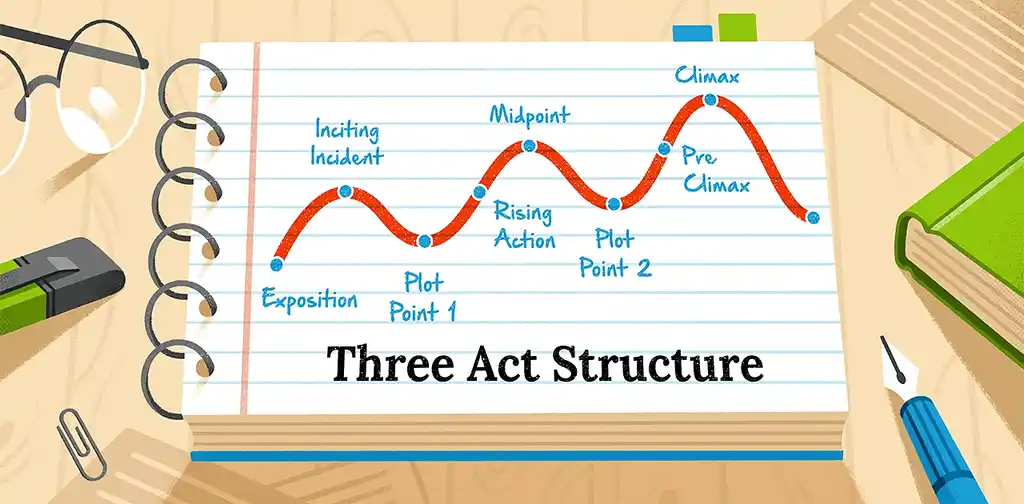

No matter how strange, experimental, or innovative a story is, it still needs to be coherently structured. When considering the right structure for your project, establish what you want the reader to feel. The Fichtean Curve, for example, is ideal for narratives driven by suspense and tension, while Freytag’s Pyramid is suited to tragedies ending in total catastrophe.

How you organize your story matters a great deal. As a minimum, you have to make sure your story opening and ending are intriguing, complete, and compelling, and your middle isn’t uneventful. If there’s anything going on that distorts the linearity of time, you also need to spend some time clarifying the chronology of your narrative and ensuring it’s communicated clearly to your readers.

If you aren’t sure about the structural choices you’ve made, a developmental edit by a professional editor is guaranteed to help you see things more clearly:

Give your book the help it deserves

The best literary editors are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

You can get creative with structure, too

Need some inspiration for structuring your story? Here are some creative literary fiction structures:

- Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts, is divided into four sections, metatextually titled Beginning, Middle (Something Happens), Middle (Nothing Happens), and Climax — the novel uses its structure to provide ironic commentary on the predictability of modern life.

- Paul Auster's 4321 tells four parallel stories following four versions of the same protagonist — all genetically identical but whose lives are shaped by the whims of random chance. As the story cycles between the different incarnations of our hero, it throws a light on the universe's infinite possibilities and how every life can hinge on the question, "What if?"

- Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude combines an overarching linear, chronological structure, with cyclical narrative elements that show how the past repeats itself, generation after generation.

- Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent completely shatters the linearity of time, jumping backward and forward in time and between characters to mirror the explosive effect of its central event: a bombing. The reading experience parallels the experience of the characters, as they try to piece together what has happened from disparate shards of information.

- Olivia Sudjic’s Sympathy follows a spiral-like structure, examining seemingly tangential information as it slowly makes its way to the core of the story. The effect is that it accurately imitates the experience of falling down the Internet rabbit-hole of a new obsession, which the novel uses as one of its central themes.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

6. Roll up your sleeves and mercilessly edit your first draft

Even if you feel your first draft is terrible, it can still emerge from the editing process as something you’re proud of. To master self-editing, check out our free course:

Free course: How to self-edit like a pro

Rid your manuscript of the most common writing mistakes with this 10-day online course. Get started now.

And one final tip, specific to literary fiction writing:

For prose, purple is not the only color

People tend to view literary fiction as something “difficult,” so they try to write in a complicated, ornate way that matches that impression. But while it’s true that readers of literary fiction will expect a carefully considered writing style, there is no single “literary” way to write, so don’t overthink it.

Instead, use whatever writing style suits your story and its aims best. A lyrical, poetic style is perfectly fine if it fits your purpose: Madeline Miller’s Circe, for example, uses language reminiscent of classical poetry to fully immerse readers in the mythical environment. On the other hand, a lot of highly regarded literary fiction is minimalist in style, pared down to a clinical and precise use of simple words to quietly convey exact moments of daily life. Examples include Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake and Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, a taste of which you can get below:

- “So many years I had spent as a child sifting his bright features for his thoughts, trying to glimpse among them one that bore my name. But he was a harp with only one string, and the note it played was himself.” — Circe by Madeline Miller

- “She has given birth to vagabonds. She is the keeper of all these names and numbers now, numbers she once knew by heart, numbers and addresses her children no longer remember.” — The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

- “He poured more gin into his glass. He added an ice cube and a sliver of lime. We waited and sipped our drinks. Laura and I touched knees again. I put a hand on her warm thigh and left it there.” — What We Talk About When We Talk About Love by Raymond Carver

The idea here is that you write without feeling self-conscious about whether your writing is literary enough. Write in a way that helps your story progress — that’s enough.

Like all writing, literary fiction is a genre to conquer by practising. Focus on the story you want to write, and not the story you think others want to see you write. It’s a freeing distinction in helping you break past writer’s block.

We hope these tips have inspired you to listen to your own instincts more and other people less — writing literary fiction should be a chance to experiment and play with your writing, not an opportunity to admonish yourself for not being original enough. Have fun!