Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

3 Types of Irony: What's the Difference? With Examples

Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

View profile →Irony is when something happens, or something is said, that is the opposite of what is typically expected. In writing, there are three types of irony — verbal, situational, and dramatic.

- Verbal irony is when a person says one thing but means the opposite;

- Situational irony is when the reverse of what is expected happens; and

- Dramatic irony is when the audience knows something that the characters do not.

Essentially, irony is a literary device used to create some sort of juxtaposition. This can have a variety of effects, ranging from tragic to comedic to simply surprising. It all depends on how you use it!

To help you understand this technique, let’s dig into the three common types of irony — with examples of irony from books, movies, and more.

1. Verbal irony

Verbal irony is where the intended meaning of a statement is the opposite of what is actually said. People and characters alike use it to express amusement, emphasize a point, or to voice frustration or anger.

You’re likely to encounter verbal irony in everyday conversation! It often takes the form of sarcasm, which is generally used to criticize or dimiss something. Keep in mind that verbal irony and sarcasm are not exactly the same — sarcasm is usually negative in intent and tone, while verbal irony can be more positive — but there is a good amount of overlap.

Q: What daily writing routines can help authors maintain consistent productivity?

Suggested answer

+ Never underestimate the power of enough sleep. This can cure more things than we know - how we show up, what we're capable of tackling each day.

+ Nourishing food to fuel the mind.

+ Movement - even if it's a walk around the block listening to a podcast, music or just deep in thought (often the best times when ideas arise).

After these three things are locked in:

+ Quiet, undistracted time blocks (even if it means phone in another room for 90 mins)

+ A laptop that has nothing else except Word on it (no website access).

+ For those who are visual, keeping a yellow sticky note daily "checklist" on a wall, to encourage a daily writing tally.

+ Ask for feedback for continual improvement.

Leoni is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There are four things that I consider before settling in to write.

What sounds are there? The best is silence, but in a city environment this is impossible. If there are specific loud that I want to block out, I listen to drone music. This consists mostly of long, sustained notes (no melodies) and comes from the American and German post-war experimental musical traditions. The texture of the sounds is often rich which works for this purpose quite well. It has a meditative effect. Failing this, music without lyrics is also good.

What is my phone doing? Just switch it off.

Social media. Along with my phone, this is designed to distract. What I do is log out of my social media accounts. If I automatically go back in, I'm then met by the login page. This doesn't sound like much of a difference, but is just enough to nudge myself into becoming mindful of what I'm doing and what my present purpose it. And mindfulness is key.

Lastly, I take a page of Hemingway's advice: "The first draft of anything is s**t." It's ok to produce bad writing. In fact, it's totally ok; actually it's great. Why? Because my ideas are now down on the page, even if it's absolutely horrible. Nobody ever simply writes a finished product straight off the bat. I'll make it better later and that is a different process.

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Get all domestic and admin chores out the way first, so that there is nothing else on your mind when you sit down to write. Then just stick at it for as long as possible.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Here are a few common phrases that show how verbal irony works:

- “Clear as mud.”

- “Friendly as a rattlesnake.”

- “About as much fun as a root canal.”

You might notice these are all similes comparing two things which are not, in fact, very much alike — a classic construction of verbal irony!

Now let’s look at other ways that verbal irony can function, with examples from well-known media.

Overstates something small

Broadly speaking, verbal irony works by either overstating or understating the situation.

Ironic overstatement is another version of verbal irony we hear all the time. Think about someone going into a meeting and saying, “This is going to be the best hour of my life!” Or someone who wins a dollar on a lottery ticket saying, “Yeah, I hit the jackpot on that one.”

💡 Note: don’t confuse ironic overstatements with hyperbole, which are exaggerated statements that still speak to an essential truth! If a character says “I’m so hungry, I could eat a horse,” that isn’t ironic — just over-the-top.

Or downplays something big

Meanwhile, an ironic understatement downplays the impact of something that is, in reality, rather significant or severe.

For example, in The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield casually says:

“I have to have this operation. It isn't very serious. I have this tiny little tumor on the brain.”

Needless to say, this is a ridiculous understatement, given the serious nature of a brain tumor. While Holden doesn't actually have a tumor, his understatement creates a darkly funny contrast — another example of how verbal irony can be used in a comedic way.

Q: What tools or apps actually make a difference in streamlining the writing process?

Suggested answer

Today we have a plethora of excellent software programs for writing, such as Reedsy Studio, Scrivener, and Grammarly. Some writers use ChatGPT, although I would not recommend using an AI generative language model to help writing. This is because it bypasses the process altogether, replacing the writer. What would be the point of that?

Even the oldest and best-known program, Microsoft Word is still excellent. But there is one older – far older – trick to helping the writing process. This is articulating your writing ideas out load. I'm sorry if it sounds mundane and less flashy!

It is surprising how difficult this can be sometimes. Often, a writer will have an idea or set of ideas but having never explained them aloud, might struggle with clarity at the detailed level. When reading over their work, they are reminded of the ideas; the writer is not merely reading here, they are remembering things that are not on the page!

So, trying to explain it to someone who does not know these ideas is crucial. This is why critique groups are an excellent way of improving one's writing. Often – after a deep explanation and perhaps some questions back and forth – I have heard the friend or other writer say, "ok, well write what you've just said!"

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Reveals a deeper truth

Beyond surface-level humor, verbal irony can also be used to reveal a deeper truth about something. This often challenges the reader’s perceptions about that thing. Certainly, when viewed through a lens of unflinching irony, many situations are exposed for what they really are.

For a literary example of verbal irony, let’s look at the very first lines of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

Though the first line sounds complimentary, the verse as a whole is definitely not praising the Montagues and Capulets for their honorable ways. Instead, the last two lines imply the opposite — both households are equally undignified. With this, the first line gains a poetic irony.

And this verse actually serve a dual purpose: in addition to giving us some context for the story, it warns readers that all that glitters is not gold. These families may be considered “nobility”, but that doesn’t mean they always act nobly. In fact, their arrogance leads them down the opposite path — and to a tragic end for Romeo and Juliet.

Provides character insight

Finally, verbal irony in character dialogue is a great tool for characterization! As you might imagine, people who use verbal irony tend to be smart, self-aware, and often keen to make light of a tough situation.

For example, in Casablanca, the corrupt-yet-charming police captain Renault is forced to close down Rick’s club under the pretense of gambling. To show Rick (and the audience) that he knows it’s a farce, Renault exclaims, “I’m shocked — shocked! — to find that gambling is going on in here!” And indeed, in the next breath, he’s accepting his winnings from the club.

Verbal irony is also a great way to demonstrate character dynamics. Characters who use irony in conversation tend to be either gently teasing or insulting each other... or both. If you are writing a romantic comedy — or anything where characters have a “push-and-pull” dynamic — consider peppering in some verbal irony to show it.

Q: What is the most crucial piece of backstory an author should understand about their protagonist before beginning a novel?

Suggested answer

Whether in the backstory or in the current action of the book, once the reader starts reading, the author should know what their character wants. It can be a long-held desire or something new, based on changed circumstances.

There has to be a motivation and drive in the character. Or if there isn't any, and that is sort of the point of the book, you want to let the reader know why and what in their past has made them the way they are. This sort of "motivation" is a good thing to search for in each character. What has shaped them to do what they do and behave the way they behave in the story? They must stay "in character" throughout the book unless some sort of inner or outer impetus has forced them or inspired them to change their ways.

So this most crucial piece of backstory might be why your protagonist behaves the way they do, what motivates them and why, and what they want.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

2. Situational irony

Situational irony, meanwhile, occurs when there’s a discrepancy between what is expected to happen and what actually happens. It may contradict the expectations of the characters, the audience, or both — but either way, situational irony is bound to surprise.

You might think of situational irony as “the irony of events” to distinguish it from the other types of irony. However, it is not the same as coincidence or bad luck (sorry, Alanis Morrisette!).

Basically, if you buy a new car and crash it, that is coincidental and unlucky — but not ironic. But if a professional stunt driver were to crash their car on the way home from receiving a “Best Driver” award, that would be situationally ironic; it’s the very last thing you would expect to happen.

So why might a writer use situational irony in their story?

Enables a plot twist

When an audience expects something and gets something else, it often constitutes a plot twist. It’s true that not all plot twists are ironic, and not all situational irony is “twisty”. But similar to verbal irony and sarcasm, there is frequent overlap.

One of the greatest twists of literature occurs in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. At the start of the novel, we are introduced to Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton — a prisoner and a lawyer respectively, who bear a strong resemblance to each other. They also have similar taste in women; both fall in love with our young French heroine, Lucie Manette.

Though we first meet Darnay when he’s on trial for treason, he is soon acquitted and able to court Lucie, and they eventually marry. Carton’s love for Lucie remains unrequited, but he is still a friend of the family.

The climax of the novel is when Darnay is re-arrested and sentenced to death — and Carton, despite being a lawyer and in love with Lucie, decides to switch places with Darnay and sacrifice himself. It’s a fantastic twist, not only because Carton is flouting his career as a lawyer and giving up on Lucie forever, but because he’s doing so to save her existing husband!

Q: What's the best piece of writing advice for an author who wants to improve their craft?

Suggested answer

Join critique groups! These were invaluable to me when it I started writing and even taught me how to edit! Reading books will become dated with old advice, so stay up to date with blogs, trends, audiences, and read, read, read!

Stephanie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Practice and read!

In the same way that you need to practice a musical instrument to get better, you need to do the same with writing too. Very few writers will publish the first book they ever write!

The other thing that will help you to improve your writing craft is reading. Read the books that are selling well in your genre right now, not just the bestsellers from a decade ago. Study them. Look at the reviews for these books and listen to what readers are saying.

There are loads of brilliant books that will help you to write an effective novel as well (Into the Woods by John Yorke, The Science of Storytelling by Will Storr, Story Genius by Lisa Cron and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody are a few of my favourites). Even if you don't agree with everything they say (I don't necessarily agree with every piece of advice in the above!) it's so helpful to see a range of different perspectives. You'll also quickly be able to see the patterns and advice from these books in the bestsellers you read. There are also loads of podcasts, blog posts, YouTube videos and audiobooks out there too, as well as Reedsy's own masterclasses!

Siân is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This sort of situational irony can make a twist both unexpected and incredibly satisfying. Bonus points if — like Dickens — you can conjure a situation that is thematically ironic, yet develop your characters such that their “ironic” choices still make sense in context.

And speaking of themes, situational irony also often...

Emphasizes a theme or lesson

Taking a story in an unexpected direction can also emphasize a theme or moral lesson. It reminds readers that an expected outcome is not always guaranteed! Because of this, situational irony is often used to convey lessons about hubris or arrogance — especially in fables and other morality tales.

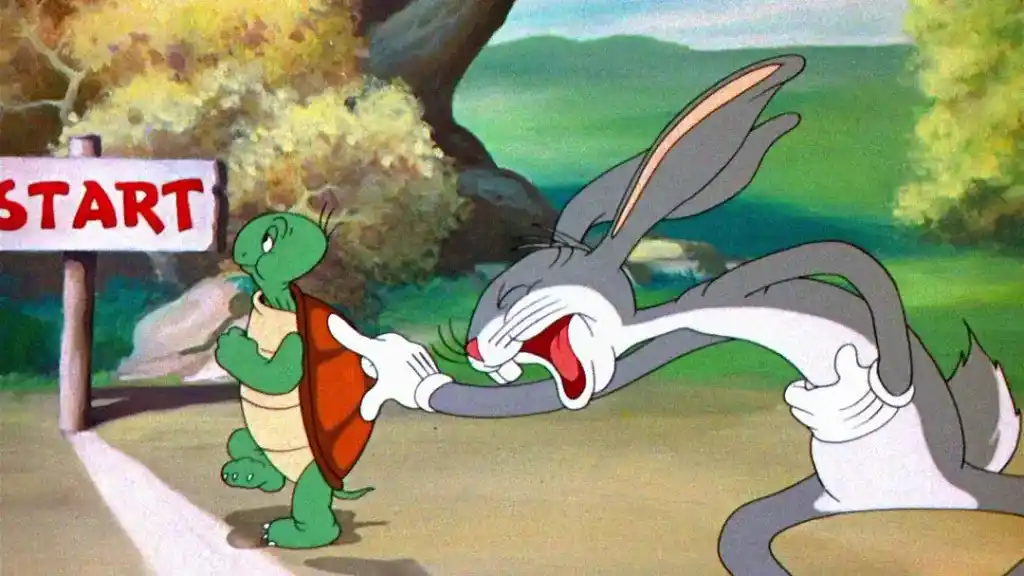

Think of Aesop’s classic fable, “The Tortoise and the Hare”. The expected outcome is that the hare will win the race — tortoises are, after all, notoriously (no-tortoise-ly?) slow.

But in a twist of situational irony, the tortoise ends up winning instead. The hare, far too confident in his lead, had decided to take a nap in the middle of the race. As a result, his reptilian nemesis overtakes him.

This is a great example of how situational irony can create an intriguing contrast between “surface” truths and “deeper” truths (reminiscent of verbal irony!). Conventional wisdom says that, yes, a hare is faster than a tortoise... but real wisdom tells us that “slow and steady wins the race.”

When done right, situational irony compels readers to interact more thoughtfully with the text — and to update their expectations going forward! To paraphrase yet more conventional wisdom, we all know what happens when you “assume”. Situational irony brings this to the forefront, making readers a little bit less likely to “assume” things in the future.

3. Dramatic irony

Finally, dramatic irony occurs when the reader or viewer knows something that the characters in the story do not. This can create a sense of unease or anticipation, as the audience waits to see how the characters will react to the situation.

Now, how can dramatic irony be used in a story?

Builds fear and suspense

Let’s hear from the master himself, Alfred Hitchcock, on how dramatic irony can build suspense:

Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence.

Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it… In these conditions, this same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating, because the public is participating in the secret. This is the nature of dramatic irony.

When readers know more than the characters do, they’re often left on pins and needles, waiting for the other shoe to drop. Will the character discover the secret we already know? What will happen when they find out the truth? What if they find out the truth too late?

All these questions run through their minds as the story unfolds, contributing to page-turning suspense.

Q: What should I do if someone has already written a book with my idea?

Suggested answer

Write it anyway!

The market for books is huge and each writer's voice is unique. You will have a different way of presenting the informaiton or telling the story, even if it's similar to someone else's.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Write a better book. There are many books written about the same topic, same ideas, same plots. You can't protect an idea, only the written expression of that idea. Go write your own book that is thoughtful, well-written, and thorough. A good book will find an audience.

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

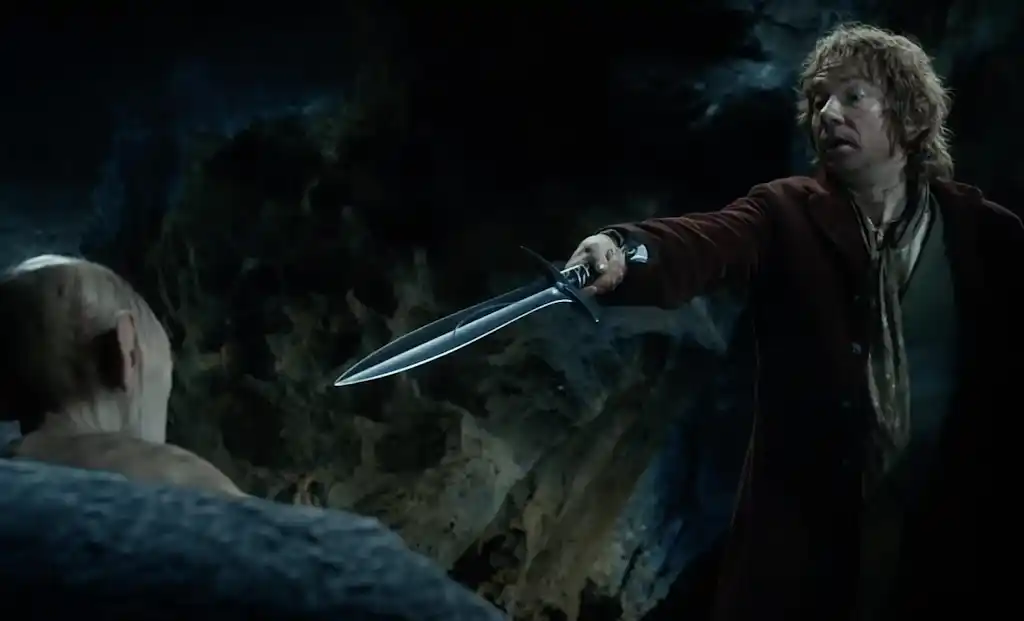

For a classic scene-level example of dramatic irony, let’s look at a pivotal scene in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. This prequel to the Lord of the Rings trilogy sees Bilbo Baggins and his companions traveling to the Lonely Mountain, preparing to battle the dragon Smaug.

On the way to the mountain, however, Bilbo faces a different foe: Gollum, who’s been driven insane by the power of the One Ring. As Bilbo approaches Gollum’s lair, Gollum drops the Ring and is unable to retrieve it. But as luck would have it, Bilbo stumbles upon the Ring himself... and takes it without realizing its immense (and dangerous) power.

This leads to a tense stand-off between Bilbo and Gollum that’s fraught with dramatic irony. We as the audience know that Bilbo has the ring, but Gollum doesn’t. On the other side of the coin, we know that the Ring is incredibly dangerous — but Bilbo doesn’t know that. As they play their way through a game of riddles, we wait with bated breath to see what will be revealed.

📚 For some truly impressive suspense-building, check out this list of the 50 best suspense books of all time.

Elicits sympathy for a character

Another way that dramatic irony works is by making us feel sympathy for the affected character(s).

Think, again, of Romeo and Juliet: Romeo kills himself thinking that Juliet is dead, but the audience knows she’s faked it. When they both end up dead, it feels like a truly avoidable tragedy. Talk about a gut punch!

Another way this can work is when we, the audience, know something that will emotionally impact a character in a big way... but the narrative is taking its sweet time with the reveal. So as we wait for this revelation, we can’t help sympathizing with the poor sucker who doesn’t know what’s coming — and hoping (against all odds) that things could still be okay.

Q: How can authors protect their rights when publishing, especially in the age of AI?

Suggested answer

I don't think anyone can fully protect themselves. If you act in good faith you will find that most other people will do the same. There will always be rogues, but selling books is hard enough if you are the real author, even harder if you have stolen it.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Let’s stick with Shakespeare for another example here — but remixed for the modern age. In the 1999 film 10 Things I Hate About You, bad-boy transfer student Patrick Verona is on a mission to seduce the cold, aloof Kat Stratford. But what Kat doesn’t know is that Patrick was paid by one of their fellow students to flirt with her.

As their relationship evolves into genuine connection, the stakes get higher. What will Kat do when she discovers the truth? This dramatic irony lends a bittersweet edge to their scenes together, making it all the more painful when Kat finds out about Patrick’s deception — at their prom, no less!

But though Kat is (justifiably) upset, she forgives Patrick when he pleads for her forgiveness... and uses the money to buy her a vintage electric guitar. As Shakespeare would say: all’s well that ends well.

In fact, quite a few romance tropes rely on dramatic irony. Think about the “enemies-to-lovers” trope — it only works because the audience knows that the pair in question will get together.

Or think about “slow burn” romances, where nothing happens between the couple for a long time. As readers, we stay invested because we understand that something will eventually happen... and our patience will be rewarded.

Sets up comical misunderstandings

Finally, on the flip side, dramatic irony can also be used for comedy. That is, the big revelation can be funny rather than tragic!

Just think of how often misunderstandings happen in sitcoms. In these cases, when the viewer knows something that a certain character doesn’t, it makes for comedic tension — rather than stressful suspense.

Case in point: in season 5 of Friends, Chandler and Monica start dating, and the show derives a lot of comedy from them trying to keep it a secret. As viewers, we obviously know they’ve struck up a romantic relationship — but for a long time, the other “friends” have no idea.

Even as they start to find out, one by one, there’s still plenty of dramatic irony to savor until ALL of them know. This leads to comedy gold such as Chandler kissing everyone goodbye, Joey sacrificing his dignity to cover for Monica and Chandler, and, later, Rachel and Phoebe screaming to distract Ross because he’s the last to know.

The more people involved (and the more degrees of understanding!), the more comedy you can wring out of dramatic irony — so if you’re ever writing your own sitcom, don’t forget about this tried-and-true technique.

Want more examples and in-depth explanations of these types of irony? We’ve broken them down even further in the next few posts in this guide — starting with verbal irony.

3 responses

Katharine Trauger says:

08/08/2017 – 05:39

I once received a birthday card telling me that irony is the opposite of wrinkly. But I do have a question: I believe, as you related to Hitchcock and I think about his works, that he used irony extensively, even more than one instance in a piece. It's a lot to remember and I've certainly not examined his works to verify that. However, I wonder if, although his works were beyond successful and loved by many, just how much irony is acceptable in today's writing. I agree it is a great device, but can it be overdone? Also, I am writing a piece which has what I believe an ironic ending. Is that a bad place to put a huge departure from the expected? I think O'Henry did that a lot, like when the man sells his watch to buy combs for his wife, and she sells her hair to buy a chain for his watch... But today, how much is too much and will readers come back for more?

↪️ Jim Morrison replied:

20/06/2018 – 21:42

While irony can be overused, it is not a bad thing to use irony - even to end a book. "Story" by Robert McKee discusses irony as an ending and explains how to use it and when to use it. As to your question about how much irony is accepted in today's society, I would say that it is more acceptable than before. With today's writing - particularly in theater - irony is a heavily used element. Thor: Ragnarok, for example, is dripping with ironic situations. Satire, the personal wheelhouse of Vonnegut and Heller, is not only a highbrow version of sarcasm, it is also heavy on the irony. So I say, personally, be as ironic as you want, just, as mentioned in the blog, be careful you don't overuse it to the point that the use of irony becomes ironic (i.e. you lose the audience). Cheers and happy writing.

Naughty Autie says:

30/05/2019 – 15:37

There is a blog which does not allow comments, yet it's called 'The Conversation'. Funny, I always thought that a conversation always took place between multiple people.