Blog •

Posted on May 01, 2020

The Lean Publisher: Evolving in the Freelance Economy

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Note: This white paper was first published in May 2017

The freelance workforce is developing rapidly, as is the publishing industry’s reliance on outsourced professionals. To derive benefit from this evolving publisher–freelancer relationship, structural changes need to be made in-house to accommodate “out-of-house” employees.

This white paper examines the publisher–freelancer relationship from the creative, management, and legal angles, and identifies how publishers can navigate the growing freelance economy successfully. It features contemporary commentary from a variety of publishing executives and freelancers from the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as predictions for the future of lean publishing and the freelance economy.

JOIN OUR NETWORK

Supercharge your freelance career

Find projects, set your own rates, and get free resources for growing your business.

Introduction

The freelance economy is exploding and has been for some time. According to the 2017 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey, 51% of executives around the world reported that their organizations planned to increase the use of flexible and independent workers over the next three to five years. Upwork’s Freelancing in America 2016 survey revealed that 35% of the American workforce was made up of freelancers, while IPSE’s Exploring the UK Freelance Workforce in 2016 report confirmed that two million people were working as freelancers in the United Kingdom.

This explosion is rippling its way into publishing houses, and it has the potential to change their internal structures. While independent contractors are hardly a novelty in the publishing industry, they have historically served as a hidden resource called upon in times of crisis. These days, they are the cogs that keep the gears of the publishing world turning. Such changes have led to a corresponding boom in the use of online marketplaces (like Reedsy), which offer freelancers the opportunity to promote themselves and provide employers with an effective way to scope out prospective talent. What makes Reedsy unique, though, is its niche focus: experienced freelancers are hired in an environment catering specifically to the needs of publishers.

In this white paper, we examine the evolving relationship between publishers and freelancers to consider how publishers can successfully ride the wave of the growing freelance economy to their benefit. To this end, Reedsy has identified three aspects of the relationship that are likely to be most significantly altered by the upsurge in outsourcing:

- creative integrity and maintaining a strong brand when working with numerous freelancers;

- project management and minimizing the time consumption of hiring freelancers at scale;

- legal issues and the potential implications of working with freelancers.

The paper concludes by looking forward and posing a few predictions for what publishers might expect next, including an increased reliance on freelancers, evolving worker classifications, the establishment of procurement departments in publishing houses, project management tools tailored for publishing, and internal training for freelancers.

Q: How has publishing changed since you started your career?

Suggested answer

When I landed my first book ghostwriting project, it was through my literary agent who was helping a Big 5 publisher find a ghost to work alongside an author who was behind in writing their book. I finished that project successfully, the book sold well, and I earned a reputation as someone who could get things done quickly.

From there I started receiving regular projects from major publishers. All the ghostwriting work I did 20 years ago was for traditional publishers.

But that started to shift and soon the leads I received were directly from aspiring authors, and then from hybrid and independent publishers. In the last five years, nearly all of my projects have been with authors who were planning to produce and distribute their books through hybrid and independent presses.

The percentage of authors working with traditional presses has declined and the percentage opting to work with hybrid and independent presses has skyrocketed. There are still great reasons to pursue a traditional book deal, and some of my clients do stay on that path, but more clients are choosing to explore hybrid publishing instead today.

Marcia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Creative Integrity: Maintaining a Strong Brand When Working with Freelancers

The challenge of maintaining a consistent brand while increasing reliance on freelance talent is a common concern of publishing houses, in particular concerning how the change might affect their creative vision. However, if undertaken efficiently, outsourcing need not be a threat to, or potential dilution of, a publishing house’s brand; in fact, hiring freelancers for particular services can actually bolster a brand’s strength.

Hiring freelancers allows in-house staff to focus on the overarching vision

Canadian author and columnist Russell Smith observed that “there was a time when a particular editor’s artistic vision and personal whimsy defined a publishing house’s program. That editor would be trusted to make decisions that were intellectually consistent and not necessarily the most lucrative in the short term.”

The practice for traditional publishers to outsource copy-editors and proofreaders has allowed in-house staff (of acquiring editors and developmental editors) to focus on decision making that furthers the company’s vision rather than word choice and grammatical correctioness, or eradicating typos. For instance, Wiley’s Dummies imprint, one of the most recognizable brands in publishing, offers its freelancers comprehensive manuals to which they can refer when copy-editing and proofreading, to ensure standards are maintained and requirements are met.

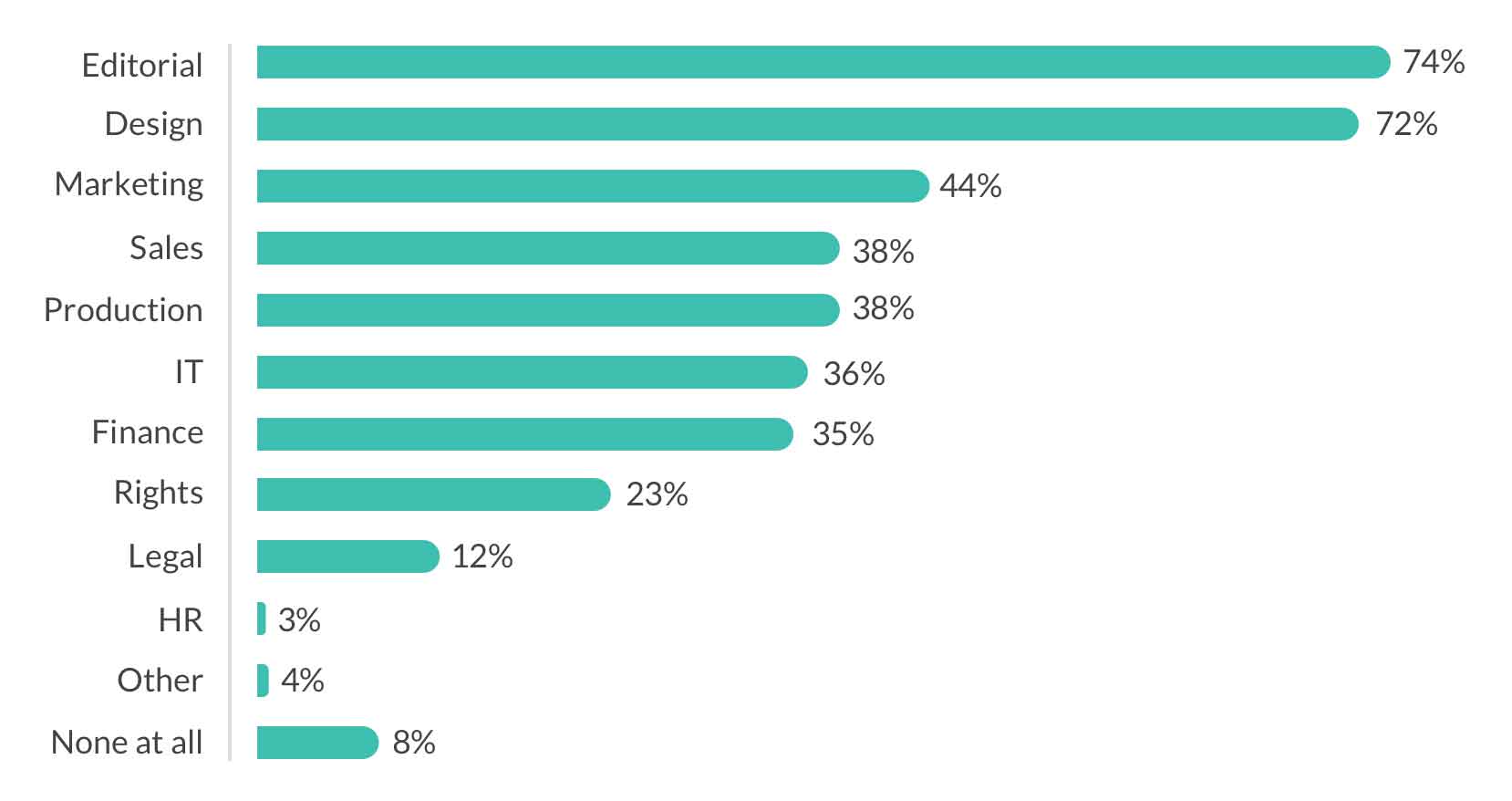

In 2015, Nielsen polled several UK publishers for the Independent Publishers Guild Autumn Conference regarding the services for which they use freelancers:

Branding can be preserved with strategic timing

For Helen Wicks, Creative Director at Bonnier Publishing, maintaining an in-house style is all about scheduling when to bring a freelancer on board for a project: “Our artistic heritage and artistic integrity are very important parts of Bonnier. Often, books develop as they are put together, and we like that process to occur in-house, in a much more labor-intensive way. However, once a style has been set, I’m happy to put work out.” In other words, hiring freelancers for projects that have already been developed (for which most “artistic” decisions have been made) removes the worry of inconsistent branding.

Whereas full-time staff can provide value in terms of their in-house and industry knowledge and standards, working with freelancers can give publishing houses a leg up by providing profession-specific knowledge. This is especially true when distributing content in new formats or producing work for unfamiliar markets. According to the Fourth Annual E-book Survey of Publishers, compiled by Aptara and Publishers Weekly, about 55% of publishers outsource work due to a lack of internal capabilities and resources. And Wicks confirms that, in instances where a specialist is needed, Bonnier does look to trusted freelancers to develop new projects from the get-go.

“Often, books develop as they are put together, and we like that process to occur in-house, in a much more labor-intensive way.

However, once a style has been set, I’m happy to put work out.”

Helen Wicks, Creative Director at Bonnier Publishing

A strong in-house brand will be apparent to those on the “outside”

According to Lauren Finger, Managing Editor at Bookouture, “It is up to the people in-house to have clear ideas of our standards and ensure that the work we are receiving from freelancers meets those standards.” Following this argument, the end result of a project that relies on freelancers is often only as good as the brief that goes out to them and the communication that follows. Therefore, publishers can ensure that outsourcing does not disrupt in-house branding by taking the time to carefully convey both project-specific and critical institutional knowledge to freelancers as they are brought on board. It can be assumed that in-house staff undertakes market research to decide on a creative strategy for books; if this work is already being done, publishers should ensure that it is shared with the freelancers who make a project happen.

Outsourcing can provide a creative boost

Working with freelancers need not only be a backup option when a publisher’s to-do list has grown too large for in-house staff to handle. Bringing on outside professionals from all areas of the globe can boost creativity and ensure that in-house teams do not burn out, grow stagnant, or fail to innovate. As Tania Wilde, Pan Macmillan’s Head of Editorial Services, says, “We often look for fresh eyes at the copy-editing and proofing stages to raise helpful queries and make valuable suggestions. In-house teams are often too close to the project by then.” In this way, an outside perspective doesn’t necessarily decrease the consistency of a brand, it breathes new life into it—a benefit that shouldn’t be overlooked, as companies that foster creativity are three times more likely to see 10% growth in annual revenue than companies that do not (McNeal, 2016).

A strong brand keeps up with the times

While many articles and reports have heralded the return of print books by pointing to the “slump” in publisher e-book sales over the past two years, others have been quick to point out that those celebrating the return of paper are jumping the gun (Ingram, 2015). True, according to the Association of American Publishers, major publisher e-book sales fell by nearly 25% in 2016. However, sales of independently published e-books have been growing. This suggests that publishers are losing e-book market shares to indie authors and Amazon publishing (read more about that here) imprints, rather than that the success of digital books and their consumption is dropping overall.

While the sales of traditionally published e-books may have been dropping in comparison to their print versions, according to the 2016 Trade Publishing by the Numbers report from the author-maintained website Author Earnings, the sale of e-books on Amazon, in general, grew by 4% in 2016. Therefore, as the report advocates, perhaps the more pertinent perspective for publishers looking forward is not print versus digital but bricks and mortar versus online. Some publishers have already embraced this challenge: for example, in 2011, Simon and Schuster announced the addition of a digital sales team, thanks to the rising sales of e-books. Other companies have developed from the ground up around the e-book market: Open Road Media, for instance, was established in 2009 to mine publisher backlists for books that had never before been distributed in e-book format. In this way, Open Road took advantage of the burgeoning e-book market to introduce a new demographic of readers to older books.

For publishers to reclaim some of the digital markets, it is crucial to cultivate a brand that is not only focused on B2B but also on consumers—after all, 41% of traditionally published print books sold in the United States were purchased online in 2016 (Author Earnings, 2016). This requires acquisition and production to develop in a way that strategizes around audiences, as opposed to just businesses, and, within this approach, outsourcing specialists will be more critical than ever—and not just for technical services. In general, freelancers with knowledge of digital marketing will be crucial in every department for publishers who are looking to maintain a brand that preserves their creative heritage and integrity while still keeping in mind their new buyers: the public.

Project Management: Minimizing the Time Consumption of Hiring Freelancers at Scale

Many publishers do not require a full-time staff year-round, and can, therefore, cut costs by having a smaller in-house workforce and simply outsourcing at the time of need to freelancers. In the first place, outsourcing can reduce costs as expenses devoted to training in-house staff are decreased. This is no small detail as, according to Training magazine’s 2015 Training Industry Report, large companies spent an average of $12.9 million on training, midsize companies invested about $1.4 million, and small companies averaged about $350,000.

How outsourcing can free up time

Outsourcing eliminates the administrative time spent on setting up health benefits, insurance, and paid vacation time. Furthermore, commissioning freelancers for specific projects can decrease the amount of time devoted to sourcing and hiring in-house staff, which is typically much more time consuming as hiring a full-time employee is a greater and more long-term commitment. Lastly, because freelancers often work remotely, outsourcing reduces the need for large amounts of office space and lowers office supply costs. But, to benefit from the decreased commitment and costs of hiring freelancers, publishers must have the appropriate systems and processes in place to ensure that in-house staff responsible for hiring freelancers are not continuously occupied with onboarding duties.

Publishers have tackled this challenge in several ways, depending on their size, resources, and philosophy. In the smallest publishing companies (those with one to five employees—the category to which the vast majority of the industry in the United States belongs), the publisher or managing director, acting as a project manager, oversees the whole production process.

In many bigger publishing companies, the task of sourcing, contracting, and managing freelancers falls to each department. Thus, in-house editors will source freelance copy-editors and proofreaders; art directors will source illustrators and cover designers; and marketing managers will source freelancers for video creation, website design, or social media management.

Check out this post about how freelance illustrators can find gigs and this post for cover designers.

Depending on the structure of the company, such project management will either be shared among respective departmental team members (e.g., each editor will oversee the editing process of the books they work on). This may also fall to a dedicated managing editor, head of production, or project manager. While the outsourcing of freelancers does ultimately need to be managed in-house by a person, turning to project management systems can make the job of that person easier. This allows them to maintain a continued connection with freelancers—even after a project is complete—so that company knowledge and branding are preserved.

Marketplaces are a good resource for sourcing freelancers

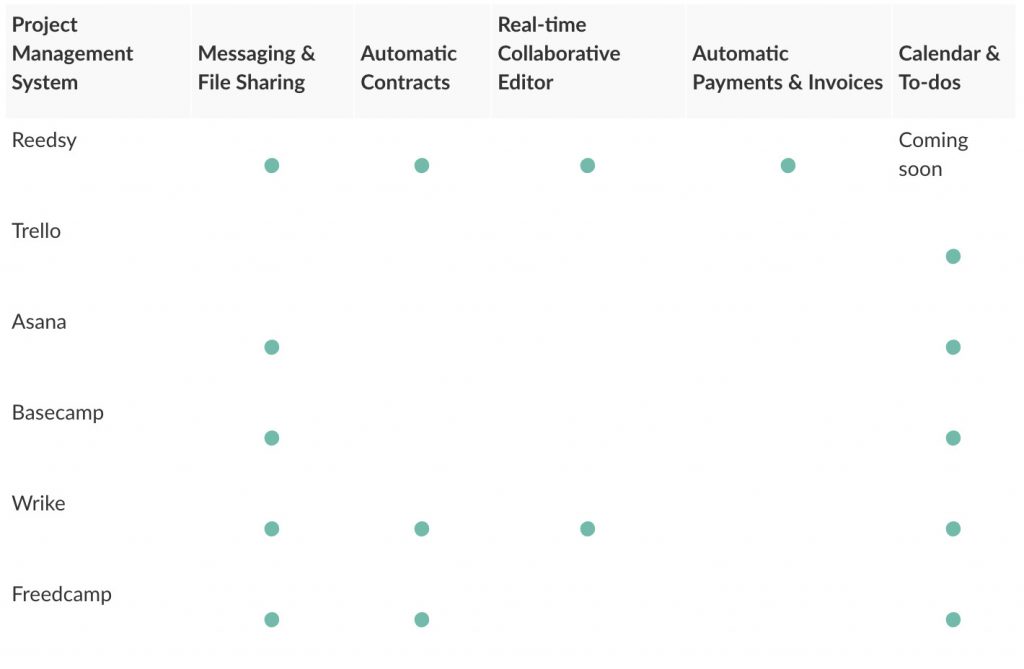

Marketplaces play an important role for publishing houses looking to outsource at scale, as they help companies grow their pool of freelance specialists quickly. This is why more and more publishers are now turning to marketplaces instead of local agencies to hire freelancers. Legitimate marketplaces thoroughly vet freelancers before representing them, thereby supplanting the less efficient word-of-mouth recommendation system many publishers have traditionally fallen back on for sourcing professionals outside of their already-established pool of freelancers. A comparison of several such marketplaces currently available for publishers to use is presented below.

Comparison of marketplaces

In addition, marketplaces absorb some of the risk and labor involved in outsourcing. According to the study A Labor Market That Works: Connecting Talent with Opportunity in the Digital Age prepared by McKinsey Global Institute, adoption of online talent platforms can increase output by up to 9% and can reduce costs related to talent and human resources by as much as 7%. For instance, when hiring freelancers, companies commonly must prepare several customized documents, such as statements of work, contractor agreements, requests for proposals, project descriptions, etc. The administrative work that accompanies these documents (creating, sending, and signing them) can be time-consuming. On many marketplaces, including Reedsy, contracts are automated, and therefore the whole process is streamlined for the hiring publisher.

Jenny Croghan, Vice President of Editorial Production at Callisto Media, clarifies this point. “Marketplaces such as Reedsy are the types of tools we want to rely on more so that we can continue to grow, but not have to continually find new editors, copy-editors, and so forth. As the company goes from less generalist to more specialist, we will want a streamlined way of increasing our freelance pool that each department can depend on.”

There’s no project management without communication

Communication is one of the most important aspects of project management—especially when it comes to working with freelancers. As Matt Haslum, former Consumer Marketing Director at Faber & Faber, advises, “It’s vital to make sure that the freelancer feels connected to the team and project.”

It seems almost paradoxical that an endless array of communication options are available to us, and yet the biggest concern publishers have regarding outsourcing remains disorganized communication. The challenge seems to be in abstaining from micromanaging, while also ensuring that freelancers thoroughly understand a project and managers are kept in the loop throughout.

Pan Macmillan Studio Manager Lloyd Jones weighs up such communication considerations:

“If we think a project will be relatively easy—when the brief is quite open, and without the need for a lot of back-and-forth between designers and editors—it feels like a good opportunity to outsource. This won’t need as much managing.”

Likewise, Bonnier’s Helen Wicks admits, “I used to be fairly reluctant to use freelancers, as I found it saves time to keep design in-house, and it’s easier to communicate and to sort things out. There’s always the danger with freelancers that they won’t touch base during a project.”

Many managers, including those at Bonnier, Macmillan, and Faber, rely mostly on email and phone/Skype calls to communicate with freelancers during a project. The upside of this is that email is already an ingrained part of our daily lives. For communication between publishers and freelancers to be efficient and effective, it should be part of a routine that is easy to incorporate into your schedule.

However, while email may be a natural communication device, it is not an effective project management tool. For that, there are numerous options: Trello, Asana, Basecamp, Wrike, Freedcamp… the list goes on. Moreover, not only do these tools facilitate task management, but many are also efficient communication resources. The following table compares the project management features offered by a representative selection of these systems.

Comparison of Project Management Systems

Testing the various platforms that aim to streamline communication between managers and workers may require considerable time and effort. In the end, finding the one that meets your needs will undoubtedly help you become much more efficient and organized in your approach to project management.

Callisto is an independent publishing company that uses proprietary technology to mine data for topics of consumer interest. Authors are employed on a freelance basis by the company to write books based on these identified potential “best-selling” topics. The whole book process, from the writing stage through production relies on freelancers: authors, developmental editors, copy-editors, proofreaders, production professionals, such as compositors and indexers, cover designers, illustrators, etc. are almost always outsourced. To manage such a large and diverse number of freelancers, Callisto has implemented Basecamp as its project management tool of choice.

“It’s the best way to gather all the different conversations happening in multiple teams and a lot of outsourced conversations with freelancers.”

Jenny Croghan, Vice President of Editorial Production at Callisto.

Tips for successful collaboration—from freelancers themselves

Several Reedsy freelancers who have been contracted by publishing companies also cite communication as one of the bigger challenges to an effective collaboration, as illustrated through the following advice.

“Make sure someone is dedicated to liaising with freelancers”

Freelance editor Leah Brown emphasizes the importance of communication on the part of the publisher when they are bringing a freelancer on board for a project: “Make sure someone is dedicated to liaising with freelancers—someone who has the time and energy to respond to queries quickly and clearly.”

“Never assume an in-house process is an industry standard”

According to freelance editor Maleah Bell, it is important to never assume anything should go without saying, or that an in-house process is an industry standard. Publishers can ensure clarity by “providing freelancers with a list of expected tasks or checklists for each project, as well as a style sheet. That way, there are no miscommunications in regards to expectations.”

“Have paperwork prepared ahead of time”

Freelance editor Katie Salisbury encourages publishers to make sure they have the appropriate paperwork prepared ahead of time, if they are not hiring through a marketplace that automates this process. “As a freelancer, working with companies when there’s a lot of red tape or that haven’t yet finished their hiring agreements is difficult. You spend a lot of time waiting around.”

Legal Issues: Potential Implications of Working with Freelancers

In a time when the boundaries between freelancers and full-time employees have become blurry, it has never been more important for publishers to have a thorough understanding of the legal implications of working with freelancers. In an industry such as publishing, where hiring freelancers is commonplace, companies would be wise to play it safe: lower taxes or avoiding costs of employee benefits are simply not worth the risk of a costly, time-consuming dispute with tax authorities.

You can read more about how to manage taxes as a freelance publishing professional here.

An enduring boom of the freelance economy will likely lead to the continuing development of legislation designed to protect the livelihoods of freelancers. The following sections outline current legal implications employers should be aware of when hiring freelance professionals.

In the United States

In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates that employers have misclassified millions of workers as independent contractors. To prevent companies from hiring freelancers to do the work of full-time employees to reduce their tax burden, the IRS published a form that misclassified employees can submit to report their employers.

It is also not uncommon for employers to engage in misclassification due to error. As a general rule, the IRS states that when work being carried out is controlled by an employer, the individuals doing said work are considered employees. If the work is controlled by the individual undertaking it, then he or she can be considered self-employed. However, the question of who retains control over work can be complicated. Employers can consider the following criteria when assessing how to classify a worker:

- Behavioral: Does the company control (or have the right to control) what the worker does and how the worker does their job?

- Financial: Are the business aspects of the worker’s job controlled by the payer? (This includes things like how a worker is paid, whether expenses are reimbursed, who provides tools/supplies, etc.)

- Type of relationship: Are written contracts or employee-type benefits (i.e. pension plan, insurance, vacation pay, etc.) available to the worker? Will the relationship continue, and is the work being performed a key aspect of the business?

Keeping these three aspects of an employee’s role in mind can help publishers ensure they are not engaging in accidental misclassification.

In the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, there are also legal implications for working with the same freelancer over and over again. The IR35 tax law was created to identify individuals who are engaging in full-time work while classifying themselves as freelancers in order to pay reduced taxes. However, IR35 currently affects contractors, rather than companies.

To determine whether an individual is an employee or a contractor, the following criteria apply:

- Control. If contractors are told by their clients where, when, and how to complete the tasks documented on their contracts, they pass the control test.

- Substitution. If contractors cannot send replacements, or substitutes, to complete the tasks for clients on their behalf, they pass the substitution test.

- Mutuality of obligation. If contractors expect clients to give them work—and clients expect contractors to complete it—they pass the mutuality of obligation test.

If a contract is “inside IR35,” the contractor is actually an employee, and a deemed salary calculation should be run to declare PAYE and National Insurance on 95% of the contractor company’s income, allowing up to 5% to cover the costs of running the company.

As of April 2017, companies in the public sector have had to ensure that contractors they commission are genuinely self-employed. This new measure might be transferred to the private sector at some point, too, which could lead to some publishers paying a potentially hefty price if Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs was to successfully challenge their assessments.

Where the United Kingdom differs most significantly from the United States in regard to classification of employees is that there is an intermediary status between employee and self-employed; this is known as “worker” status. In a nutshell, all employees are workers, but not all workers are employees. A worker who is not considered an employee is an individual contracted to personally provide certain services but who is not entitled to a contract of employment. A self-employed individual is contracted to provide certain services, but the circumstances of the completion of these services are entirely up to them. They can even have someone else complete contracts on their behalf. The issue here is that self-employed freelancers hired for short-term contracts on an ongoing basis by a publisher run the risk of having to be classified as workers, due to the long-term work relationship that exists. A noteworthy example of this can be seen in the October 2016 employment tribunal ruling that stated Uber must pay drivers in the United Kingdom a national living wage and holiday pay.

Predictions for the Future: The Publisher–Freelancer Relationship

Publishing processes and formats have been changing, and the freelance economy has been growing. Combined, these two continuing trends are shifting the industry. Exactly how the shifts will ripple through the internal structures of publishing houses is still up for debate. Nevertheless, we have come up with five predictions regarding how the growing freelance economy might continue to change the publisher–freelance relationship.

An increasing number of publishers’ operations will be structured around the use of freelancers.

Callisto’s Jenny Croghan says, “We’re not like publishers that used to have mostly in-house staff and are now outsourcing more work; the editorial department has always been built around freelancers. I think it’s part of the nature of being located in Silicon Valley; the area infuses you with the new economy of having a variety of individuals work for you to increase creativity. Callisto Media is probably modeled more after an Uber or an Airbnb as opposed to traditional publishers. Although, I do feel that in the future, more publishers will do it this way. I recently spoke to someone in one of the Big Five companies, and they are outsourcing everything to a full shop—the book simply comes back completed.”

In the United States, there will potentially be a third classification between “employee” and “non-employee.”

As of 2016, 55 million freelancers were working in the United States, which equates to 35% of the American workforce. Together, they earned an estimated $1 trillion in 2016. Since 2014, the number of working freelancers has been growing by almost a million per year, so it’s not hard to imagine that this number will continue to grow.

According to Upwork’s Freelancing in America 2016 survey, around 63% of people report choosing to freelance, as opposed to becoming a freelancer due to external circumstances. The reasons people become freelancers are varied, but the top three reported were: (1) wanting to be their own boss, (2) schedule flexibility, and (3) location flexibility.

With a boom occurring in the freelance economy, and a storm of lawsuits being filed against companies like FedEx, Uber, Lyft, Handy, etc., it is also not hard to imagine the potential evolution of a standard work contract between a freelancer and a publisher. In the future, what will differentiate a non-employee from a quasi-employee (someone who is not full-time, but is tied to an individual company as a freelancer)? Will this force a middle ground to be classified between a non-employee and an employee (much like the “worker” status in the United Kingdom), so people who enjoy freelancing can maintain their independent status and devote longer periods to an individual company without having to become an employee simply to avoid misclassification? If more and more publishers do start to rely on freelancers instead of full-time employees, will these ongoing freelancers, or quasi-employees, begin to expect certain benefits from employers?

Envisioning what these benefits might include, freelance editor Katie Salisbury remarks, “One of the hardest parts of being a freelancer is paying for health insurance. It’s expensive to pay for even the average premium, in which the health care provided is limited. Given the current situation and the potential for Obamacare getting repealed, it’s one of the trickier parts of freelancing. In an ideal world, quoting a fee for my work and then add a percentage on top of that for the health benefits I pay for myself would be amazing.”

Freelancing in numbers, according to Upwork’s Freelancing in America 2016:

- 54% of freelancers earned more money within a year of leaving their full-time jobs

- 50% of freelancers enjoy their current work set-up so much that they wouldn’t go back to a traditional job, no matter how much it paid

- 73% of freelancers said that technology has greatly enabled them to choose this career style

- 79% of freelancers prefer freelancing to traditional work environment.

There will be an establishment of teams specifically designed to manage freelancers.

Publishers may start instituting procurement departments or dedicated HR resources focused solely on liaising with and onboarding freelancers. These teams will likely be comprised of managing editors or production managers from each department who have a knowledge of both their specific department’s skillset and of freelance workforce management. Such roles will likely become the first- or second-most important ones in a publishing house (after acquisitions). An IRS crackdown on worker misclassification has been underway since 2013, so procurement departments will not only vet which freelancers are being hired, they will also address compliance and legal issues to ensure all workers are appropriately classified.

There will be a rise in project management tools specifically tailored to the publishing industry.

Bonnier’s Helen Wicks echoes one of the common frustrations, mentioned earlier, among publishers who outsource professionals: “When working with freelancers, there can be a lot of packaging and sending stuff out, which is time-consuming.” Regarding what would solve this frustration, Wicks suggests, “A project management tracking tool would be useful … A freelancer could log on, work for a bit, show exactly where they got to on the project, and then log off. It would allow us in-house staff to move things forward more quickly and would also provide some much-needed transparency.”

Such tools do already exist on the market: Basecamp, Trello, Asana, etc. But, as Callisto’s Jenny Croghan explains, “You have tools like Basecamp that are general project management tools, and then you have platforms that allow for an in-work flow of managing freelancers.

I would imagine that, at some point, there will be more platforms that cater to publishing and allow for streamlining of the process between publishers and freelancers. There’s definitely a market for it.” However, publishers would need to be careful with tools like this. Requiring freelancers to detail their exact tasks on a daily basis could feel quite controlling, and could again blur the lines between a freelancer and an employee. Outsourced staff might also start to feel they are being micromanaged, which can hinder creativity.

There will be more training for freelancers.

Currently, many who want to break into the publishing industry do so by first studying publishing, and then, ideally, securing a job in a publishing house. There, with a lot of hard work and dedication, they will hope to progress from junior-level positions to senior-level ones, and then on to management, and so on. However, if more and more people begin to choose the freelancing approach, there will likely need to be an alternative means of receiving the valuable business training that comes from years of working for a publishing company in-house. Perhaps this program will be established within publishing houses individually, or maybe there will be a course, separate from the formal education they may have already acquired, that certifies graduates as publishing-industry freelancers. A few publishers working extensively with freelancers already require some kind of accreditation. For instance, Pan Macmillan’s Tania Wilde explains, “If we’re looking to recruit a new freelancer, we always ask for an up-to-date CV with a list of titles they’ve worked on. We tend to ask for industry accreditation [and] training of some sort, too—usually courses run by the Publishing Training Centre.”

Conclusion: The Lean Publisher

As relayed in Publishers Weekly, in 2016, members of the Association of American Publishers reported that unit sales of print books rose by 3.3% (despite lacking a blockbuster such as 2015’s The Girl on the Train), unit sales of e-books decreased by 7.7%, and publisher revenue fell by 6.7%. Likewise, as reported by Media Business Correspondent at The Guardian, Mark Sweney, in 2015, sales of printed books grew by 0.4% (in part thanks to the adult coloring book craze), e-book sales fell by 1.6%, and overall sales rose by 1.3%. However, some publishing companies, such as Quarto, have acknowledged that the soft 2016 market could have partly been due to “uncertainty caused by Brexit.”

With unsteady print growth, declining e-books sales, and diminishing revenues, many publishers are looking to their marketing and sales teams to improve their market shares. Less frequently, they look to the production aspects of publishing—an area where vast improvements can be made by adopting a flexible, lean publishing model that effectively incorporates freelancers.

Whether publishing houses are ready to embrace these changes or they see the publisher–freelancer relationship continuing as it has done before, it is important for companies to be aware of the potential effects of this changing economy, and to prepare for them.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the following people for contributing to this white paper:

Andrius Juknys, Head of Central Sales Services, Thames & Hudson; Helen Wicks, Creative Director, Bonnier Publishing; Jenny Croghan, Vice President, Editorial Production, Callisto Media; Katie Salisbury, Freelance Editor; Kim Yarwood, Freelance Editor; Lauren Finger, Managing Editor, Bookouture; Leah Brown, Freelance Editor; Lloyd Jones, Studio Manager, Pan Macmillan; Maleah Bell, Freelance Editor; Matt Haslum, former Consumer Marketing Director, Faber & Faber; Perris Davis, Freelance Editor; Tania Wilde, Head of Editorial Services, Adult Publishing, Pan Macmillan.

Reviewed by Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

As the editor of Reedsy’s freelancer blog and a writer on the Reedsy team, Linnea has her hand in a bit of everything, from writing about writing, publishing, and self-publishing, to curating expert content for freelancing professionals. Working together with some of the top talent in the industry, she organizes insightful webinars, and develops resources to make publishing more accessible to writers and (aspiring) publishing professionals alike. When she’s not reading, she can be found dribbling on the football pitch, dabbling in foreign languages, or exploring the local cuisine of whatever country she happens to be in at the time.