Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Writing Young Adult Fiction: An Editor’s Guide to Awesome YA

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Young adult is perhaps the fastest-growing category of new fiction today. Indeed, more authors are writing young adult fiction than ever before! There’s just something about adolescence — with all its incredible triumphs and heartbreaking failures — that makes it the perfect backdrop for powerful storytelling.

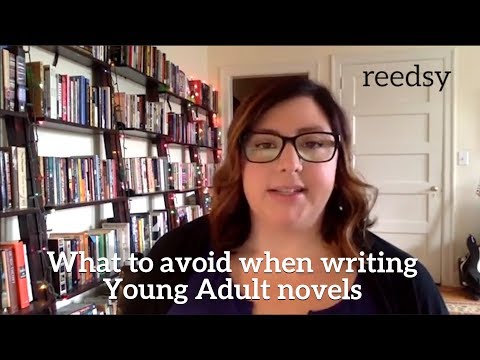

That's why, if you're hoping to create something that will stay with readers forever, writing YA is a great way to do it. One person who knows this is Kate Angelella, an experienced YA editor who's edited a number of iconic series, including Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys. In this post, she shares her top tips for how to write a young adult novel that readers won't forget.

Before Kate takes it away, let's quickly go over what YA fiction is and why it appeals to so many readers.

What is YA fiction?

Young adult fiction, or YA fiction, is literature that targets readers aged 12-18. YA stories follow teenage characters as they grapple with the unique challenges of adolescence, such as navigating relationships and finding oneself. Though originally intended to “bridge the gap” between children's and adult lit, YA has become a respected category of literature with many well-known titles in its canon.

To delve into it a bit more, most works of YA fiction would be labeled “problem novels” and/or “coming-of-age novels.” The characters in these works experience intense emotions and often existential angst as they come to grips with their place in the world. They realize that life must fundamentally change as they exit childhood and enter adulthood — a transition that results in a loss of innocence and shifting sense of identity.

Indeed, these elements are hallmarks of both classic and contemporary young adult fiction. Two perfect examples of classic YA novels are The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies. In fact, neither was marketed to teenagers, but caught the attention of young readers through their highly affecting portrayals of adolescent psychology. With the publication of S.E. Hinton's The Outsiders in 1967, YA fiction solidified into what it is today.

As for contemporary YA examples, look no further than some of the biggest bestsellers from the past few years! The Fault in Our Stars, The Hate U Give, and the Divergent series would all be classified as young adult novels. These books' massive popularity, not to mention the fact that they were all adapted into blockbuster movies, clearly demonstrates the cultural impact of well-written YA and shows that it's not going away anytime soon.

Free course: How to write a YA novel

Become the next Young Adult sensation with this online course from editor and YA author Kate Angelella.

Can adults read YA too?

Of course! Though YA fiction is (by definition) about and primarily intended for young adult readers, well-drawn YA characters are relatable to readers of any age. On top of that, the stories themselves tend to be just as interesting and profound (if not much more so!) as adult fic.

For grown-up readers who may still need some reassurance, note that well over half of YA readers are over the age of 18. Obviously, YA fiction taps into something that we all find incredibly compelling. Whether it's reliving one's own vivid teenage years or relishing the drama that accompanies someone else's, young adult fiction evokes strong emotions and reactions in all of us. Basically, it's one category of literature (note: not genre, like romance or horror) that will never go out of style.

All the more reason to learn how to write a YA novel, right? Without further ado, here are 8 essential tips for writing young adult fiction, courtesy of Kate Angelella!

1. Don’t think of YA as ‘adult fiction that’s been dumbed-down’

Some of my favorite YA novelists are accidental children’s book authors. YA pioneer Francesca Lia Block — and author/maven of some of the most lyrical prose you’ll find this side of Gabriel García Márquez — is a fine example. She did not intend to write her cult classic Weetzie Bat series as children’s books, but Weetzie was destined to be a YA protagonist for the ages. She does and says things while coming of age that would make Holden Caulfield blush, and the rest of us rejoice.

Though your character’s voice should be true to her identity and life experience, you never have to (and never should) simplify the language, story, or style choices in your novel in order to talk down to teen readers. YA authors should aspire to write at least as well as they would for adult fiction — and there are innumerable examples of YA fiction that outshine even the prettiest prose adult lit-fic has to offer.

2. Make sure your characters are the right age

The protagonist of your YA novel should ideally be between 14 and 18 years old. Think high school-age.

If you write a children’s book in which a character is twelve years old, this is a middle-grade novel. If you’ve written a book in which your character is nineteen, this is either a new adult novel or an adult novel, depending on your content.

There are, in fact, many adult novels with teen protagonists in the world. However, these books are most often considered adult literature for the reason that the books are written with an adult audience in mind. Two great examples of this are Curtis Sittenfield’s Prep and The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, both of which feature teen protagonists who are talking about their teen experiences through the lens of an adult looking back on their teen lives, rather than as a teen living that life in the moment.

This is what differentiates a book about teens from a book teens will actually find readable and enjoyable. A story told by a teen narrator as they're experiencing it, or in the recent past, is a YA novel. An adolescent story told by a now-adult with more literary, adult language and themes is no longer YA, but adult literature.

3. Focus on authenticity

Remember that writing a YA novel almost always means writing from a teen POV. Again, we should be experiencing your teen protagonist’s world as she sees it in the moment, not with the wisdom and practiced rhetoric of an adult looking back on her teenage years.

Authenticity is not just about a character’s distinctive voice, either. You should also be aware that story development needs to contain that clear ring of truth. Allison Singer, Editorial Assistant at Zachary Shuster Harmsworth Literary, cites this as one of the most common issues in the YA fiction submissions she receives:

“What turns me off most,” says Singer, “is a lack of causality — where you can tell when plot developments, especially new relationships, happen because the author wants it to, not because anything is intrinsically driving the story.”

4. Write fully-formed, three-dimensional characters

In a way, this is an offshoot of the above rule on authenticity. Your characters should have depth and dimension — just because you’re writing teen characters, doesn't mean you’re allowed to stereotype.

The most interesting characters are the ones who are multi-faceted. Protagonists who are too perfect, or antagonists with no redeeming characteristics, are boring to read (and write). After all, how can the reader connect with someone who doesn’t feel well-rounded and relatable?

“A big turnoff for me would be underdeveloped stock characters,” says Liesa Abrams, VP and Editorial Director of Simon & Schuster’s Simon Pulse imprint. “Writers who make the mistake of assuming that the inner life and potential dimension to a certain character would mirror what that writer assumed was the case for someone different from him/herself in high school. In other words… writing the ‘jock/popular’ kid as being a jerk or not smart, etc. And that classic ‘bookish quiet’ character, even, without seeing that character's tougher side.”

Allison Singer concurs: “If your characters aren’t developed well enough for their wants, desires, feelings, nuances, etc. to be evident, pretty much anything they do is going to feel like puppetry.”

5. Find the right voice for your protagonist

Voice can best be described as your main character’s personality, coming through in the words they’re using to tell their story. A lot of new writers assume that voice has solely to do with the way your character’s voice sounds in the literal words they say, which seems to make sense — but when we talk about voice, we really mean every single word on the page.

The main character’s voice is one of the most important elements of a YA novel, and it’s influenced by:

- word choice

- sentence and paragraph length

- syntax

- punctuation

- cadence

One of the biggest mistakes I see authors making in YA manuscripts is thinking that teen voice automatically means snarky and sarcastic. Though those characteristics may seem synonymous with the teen experience, and they are certainly valid choices, there are as many options for voice as there are personalities in the world — don’t limit yourself to just one.

Here are a few excellent examples of voice from Young Adult classics. The first one’s from The Princess Diaries by Meg Cabot.

YA example #1: The Princess Diaries by Meg Cabot

Lilly’s like, “Mr. Gianni’s cool.”

Yeah, right. He’s cool if you’re Lilly Moscovitz. He’s cool if you’re good at Algebra, like Lilly Moscovitz. He’s not so cool if you’re flunking Algebra, like me.

He’s not so cool if he makes you stay after school EVERY SINGLE SOLITARY DAY from 2:30 to 3:30 to practice the FOIL method when you could be hanging out with all your friends. He’s not so cool if he calls your mother in for a parent/teacher conference to talk about how you’re flunking Algebra, then ASKS HER OUT.

And he’s not so cool if he’s sticking his tongue in your mom’s mouth.

The first thing that jumps out is word choice. Words such as “like” (“Lilly’s like,” not “Lilly said”), cool, yeah, hanging out. These all have a very casual, laid-back teen feel to them.

Cabot also employs repetition to communicate Mia’s voice. Note in the first paragraph how two sentences in a row begin with “he’s cool if” and the next several sentences begin with “he’s NOT so cool if,” almost as though she’s ticking items off a list.

Through the repetition, you can feel her attitude. There is some snarkiness and drama present here, but note that it’s not off-putting or snarky to the point of meanness or cruelty, which would make us dislike her. Mia is pretty justified in feeling what she’s feeling here, and she’s not overly sarcastic. There are a few places where Cabot uses caps lock to get across Mia’s dramatic nature, but she’s not so ridiculous that we’re rolling our eyes.

YA example #2: Feed by M.T. Anderson

The next example is from the opening of M.T. Anderson’s Feed.

We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck.

We went on a Friday, because there was shit-all to do at home. It was the beginning of spring break. Everything at home was boring. Link Arwaker was like, “I’m so null,” and Marty was like, “I’m null too, unit,” but I mean we were all pretty null, because for the last like hour we’d been playing with three uninsulated wires that were coming out of the wall. We were trying to ride shocks off them. So Marty told us there was this fun place for lo-grav on the moon. Lo-grav can be kind of stupid, but this was supposed to be good.

Probably one of my favorite first lines in any book, ever. “We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck.” What does this sentence say about the main character, Titus, and the world in which he lives?

The language is casual like in Cabot’s example, but there’s a different feel to this voice. While Mia’s voice felt a bit dramatic, Titus seems just the opposite. “Shit-all” to do. Boring. Stupid. As a result, Titus comes across as kind of apathetic and impassive. And though there are some words in there that Anderson has given new meanings (null, unit) we are able to understand through context and tone that these words, too, are adding to the generally cool, dispassionate feel of Titus’ voice.

YA example #3: The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

The last example comes from the opening chapter of The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, which hit #1 on the NYT Best Seller list its first week. It’s a novel that explores police brutality and systemic racism in America.

We break out the crowd. Big D’s house is packed wall-to-wall. I’ve always heard that everybody and their momma comes to his spring break parties—well, everybody except me—but damn, I didn’t know it would be this many people. Girls wear their hair colored, curled, laid, and slayed. Got me feeling basic as hell with my ponytail. Guys in their freshest kicks and sagging pants grind so close to girls they just about need condoms. My nana likes to say that spring brings love, but it promises babies in the winter. I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of them are conceived the night of Big D’s party. He always has it on the Friday of spring break because you need Saturday to recover and Sunday to repent.

Starr is the narrator; her voice is thick and resonant on the page. Take the sentence “Girls wear their hair colored, curled, laid, and slayed.” You can feel the rhythm, the cadence of these words. Word choices like “momma” and “everybody.” Slang like “kicks” and “basic,” “laid and slayed.” From this paragraph, I can tell that Starr is very matter-of-fact. There’s no room for sarcasm or dramatics or even apathy, as in the other examples I’ve read from today. She’s telling it like it is, no frills. No fuss.

In all of these examples, see how the punctuation (or lack of punctuation) and sentence-and-paragraph length play a role in the feel of a voice too.

6. Don't write around heavy subject matter

One of the most common statements I hear in my freelance career? “My main character is a teen, but I don’t think my novel is YA because the content is too dark.”

Now I’m not saying that there's no such thing as too dark for the YA market (my husband, J.R. Angelella, did a superb job of showcasing that too dark can be an actual thing with his first novel, Zombie). But I will say this: remember that your target audience is experiencing sex, drugs, bad language, and all the other Big Bads you might dream up in their everyday lives. And reflecting the teen experience is what writing young adult fiction is all about.

So long as you’re writing with purpose and not just to be edgy, embracing heavy subject matter (or at least not shying away from it) is essential when writing a YA novel that is both authentic and relatable.

7. Don’t write into trends

It can be difficult to avoid the temptation of choosing your subject matter based on the latest Publisher’s Marketplace deal that just sold at auction for a “major deal.” But the truth is, trends in YA are fickle. By the time you get around to shopping your novel, the trend may have already passed.

The best way to make an agent, editor, or reader will fall madly in love with your book is to write about something that lights you on fire. Something you wake up every day ecstatic to write about, regardless of the topic’s trend status. Your passion and originality will come through, and there is nothing more infectious.

"When reviewing YA submissions,” says Melissa Nasson, Associate Agent for Rubin Pfeffer Content, “one of my biggest gripes is when I start reading and immediately feel that I've read something similar before. Originality is so important, so when I sense that an author is trying to emulate Suzanne Collins or Veronica Roth rather than telling their own story, it makes me less inclined to continue reading... if I find the manuscript too familiar, then editors (and eventually readers) certainly will too."

8. Papa, don’t preach

Some call it preaching, some call it didacticism. Whatever you call it, whatever you do, please don’t talk down to your YA reader.

By this, I mean that you should never set your main character up for a fall simply to teach him or her a thing or two. Not only will your teen reader smell the lesson cooking a mile away, but your YA novel will also suffer.

Because writing YA is not about the result at the novel’s conclusion — it’s about the journey. The journey to the emotional truth of a real, relatable human being who is in flux and figuring things out.

YA readers deserve your emotional honesty. They deserve authentic, emotionally resonant characters who show them they aren’t alone, not characters who only exist to sell moral high ground or life lessons.

To learn more about how to write a young adult novel, check out Kate's free course on Reedsy Learning, The Ten Commandments of Writing YA Novels.

16 responses

Nick says:

25/11/2015 – 15:29

Good advice here. Particularly with focusing on characterization and authenticity. The 'my novel is too dark' thing drives me crazy too. A few other things to consider: - Write in a YA voice (e.g., a little bit snarky) - Consider making the MC female (most YA readers are women) - Have some sort of romantic element I would add the caveat that not writing to trends only really applies if you're going the trad publishing path and trying to land an agent (etc). Readers like to read books similar to what they've read and enjoyed before. If you're indie publishing you can make A LOT of money piggybacking off trends. Fifty Shades of Grey, for example, started a whole genre of billionaire BDSM romances. There are YA readers out there hungry to read the next book like 'Mortal Instruments' or 'Hunger Games.'

↪️ Kate replied:

25/11/2015 – 19:18

Thanks, Nick! I'm glad you liked the article and I appreciate your feedback. Voice is incredibly important-- you're so right. I was always willing to work with an author to revise plot issues, but voice is a bit more difficult to teach. A quick side-note: though it's true that more women purchase YA titles than men, studies show that women are less likely than men to choose a book based on the MC's gender. I would argue that it's more important than ever to hear from main characters of all genders, races, cultural backgrounds, etc. Books by and for men (Chris Lynch, John Green, MT Anderson, Tim Wynne-Jones, and Ned Vizzini are among some of my favorites, just to name a few) are doing important work, and seem to be doing pretty well in the YA market to boot :) Thanks again for your feedback-- happy writing!

TigerXGlobal says:

25/11/2015 – 15:35

Great tips, Kate! In my recent work with YA authors I often encounter the 'crusader', the author who is so concerned with the teen problem they're attempting to address (showcase) that the story and character development suffer. Their passion for the dilemma topic is admirable and usually well-placed, but the book becomes (as you mention) an enormous 'lesson'. When editing, I often talk with my authors about what they read as a teen, and not what they think teens are reading now. We also talk about what emotional or mental satisfaction they were searching for as a teen reader. At this explosive and tumultuous time in every person's development, there is a grasping for understanding, the first experiments in rationalizing, and the inevitable frustration when the complexity and contrariness of the world seems so impossibly overwhelming. Most of my YA authors, in our discussions, eventually say that their teen reading was a search for validation and acknowledgement...plus the hopeful promise of someday gaining a firm foothold that would propel them into their futures. A last thought: YA books need characters that are not only well-developed as individual characters, but that provide strongly integrated and interactive groups. The group mentality, the loners, the insiders, the fringes -- teens use the constantly morphing groups all around them to navigate through their lives. Teens continually try on personalities, surf different groups, 'break up' with groups, and crash other groups. It's a violent (in terms of abruptness) time and decisions are often based on nothing more than survival, grasping the nearest group 'log' where you don't get your hand bitten off and might even get to climb up out of the uncertain waters surrounding you. Again, thanks for the great tips -- this is clip-n-save advice, especially for the newbie YA author.

↪️ Kate replied:

25/11/2015 – 18:59

Thanks for your thoughtful response! I agree that many YA readers are looking for connectivity-- a character (or author) who shows us that we're not alone in what we're thinking, feeling, experiencing.

Leanne Dyck says:

25/11/2015 – 18:19

I've written for adults, new adults and children. I woke up yesterday with this great idea for a YA. And a questions -- how? can I? Thank you for empowering me to try.

↪️ Kate replied:

25/11/2015 – 18:57

I'm thrilled to know that you're feeling empowered by this article, Leanne! Everyone has a story to tell :)

Cheryl M. says:

01/12/2015 – 22:26

What is your opinion on writing books appropriate for ya (say pg 13 ish) but the characters are adults?

↪️ Kate replied:

02/12/2015 – 14:38

I'd say that if the characters are adults, you're writing adult fiction-- even if the book is YA-audience appropriate (which many are). Unless you're saying the main character is a teen but all the rest of the characters are adults? In which I'd say that it depends on the context, but even then the MC should have friends/a love interest/others his/her age around (unless there are truly extenuating environmental circumstances).

Di Reyliner says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

Hello Kate, My protagonist is a 16-year-old who has prematurely (and illegally) enlisted with the army. Coming from a powerful political family and indoctrinated with patriotism, he is eager to serve. But what he sees in the war (some very "dark stuff") makes him challenge the agenda of his own country and if they are the "bad guys" themselves. Does this qualify as YA or is it adult fiction? A little help please.

Isti says:

02/06/2019 – 18:22

Hi, I’m a young writer and I’m trying to write a young adult novel that talks about serious subjects but I want to approach it in a humorous way that makes the reader smile. However I still want the reader to learn from the book and see the moral of it. Any tips on how I can draw the line between funny and too funny

↪️ Barbara Hilow replied:

07/07/2019 – 18:09

Try reading some Chris Crutcher - perhaps "Staying Fat For Sarah Byrnes." His approach isn't humorous, but he is able to inject humor into some serious, even devastating, situations.

Mark Cavanagh says:

23/07/2019 – 23:39

Talking voice, and age, you say twelve is middle school readers. Is that inviolable? Adding to the quandary, what if the novel is set in 1964, a supposedly simpler time. Coming of age varies, and these days... it feels wide open. What's your take on this? Does protagonist age specify YA audience as strictly as you suggest?

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

30/07/2019 – 12:15

Nothing is inviolable — but you'll be working uphill if you do decide to make your protagonist younger than your readers, you'll be going against decades of perceived wisdom. Alos, developmentally, a 12-year old and a 15-year old are very different people, regardless of whether they grew up in the 60s or now.

↪️ Bridgette Campbell replied:

27/11/2019 – 09:43

Writing is the easy part, getting those stories in front of your readers is something else. I write children's SHORT STORIES, so far 64 of them, my target age is 12-16. I write in the first person and in the vernacular as teens speak a different language from you and me. The stories are set in a girls college. I have about 15 characters to choose from. Half a story might be set in the college the second part might be set at their home. I am not looking for fame or fortune and I want to uses a pen name

Margery S Wood says:

23/09/2019 – 15:54

Do you have a suggestion for what YA novels to read if you're interested in writing about the 1960s?

Jesse says:

03/02/2020 – 16:21

What would you consider a book that starts with the main character at 2 years old and ends with them at 23, but the majority of the book is the character between 12 and 20 years old? Also most of the characters the main character interacts with are teens or young adults.