Posted on Feb 17, 2025

What is a Subplot? Definition, Types, and Examples

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Subplots add the seasoning that make stories richer, spicier, and tastier. They deepen the layers to the main plot, bring characters to life, and keep the reader engaged. In movies, they are often called B stories — secondary narratives that complement the main story.

But what is a subplot exactly, and how do writers use them? In this post, we'll break down everything you need to know about different types of subplots using examples from literature.

What is a subplot?

A subplot is a secondary storyline that runs alongside the main plot. It has its own beginning, middle, and end, but also has a clear connection to the main story, enhancing the narrative.

For instance, think of a romance novel. Though the main plot will obviously center on the couple, a subplot might see one of the characters repairing their dysfunctional relationship with their family. This could, in turn, deepen the overarching narrative by showing how resolving family issues helps the character trust their partner more fully.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

Its role is to enrich the main narrative

Subplots can be as simple as a professional rivalry or as complex as a political conspiracy, but they always serve a narrative purpose. Usually, subplots do one or more of the following:

- 🧔 Develop characters. A strong subplot allows characters to grow in ways the main plot doesn’t always allow. In Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, Pip’s interactions with Magwitch force him to reevaluate his values, leading to significant character growth and shifting his views on class and status.

- 🚀 Propel the action. The best subplots directly impact and drive the main plot. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the subplot of the escalating feud between the Montagues and Capulets culminates in the fatal duel between Tybalt and Mercutio. This directly prompts Romeo to avenge his friend’s death, which leads to his banishment and sets the famously tragic chain of events into motion.

- 🎭 Enhance genre. Subplots help reinforce genre conventions. In The Shining by Stephen King, Danny’s psychic abilities serve as a subplot that deepens the horror genre, adding supernatural dread.

- 🎨 Reinforce themes. A subplot can mirror, contrast, or expand on the story’s themes. In The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, the Jew hiding in the basement paints his own story over the pages of Hitler's Mein Kampf and gifts it to Liesel. This subplot reinforces the novel’s themes of resistance and the power of words.

- ⌛ Vary pacing. A well-placed subplot can prevent a story from feeling monotonous or overwhelming by shifting between moments of high tension and quieter scenes. In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling, Hermione’s campaign to improve the rights of house elves introduces slower, thought-provoking moments amid the high-stakes challenges of the Triwizard Tournament.

- 🔍 Foreshadow future events. Some of the best subplots introduce hints about major moments later in the story, making them seem more natural when it comes to them. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis, Edmund’s early interactions with the White Witch foreshadow his later betrayal.

- 🗺️ Build the world. In fantasy or sci-fi, subplots often explore different cultures, histories, or conflicts that immerse the reader even more in the story’s world. In The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, Bilbo’s encounters with the elves of Rivendell and the dwarves of Erebor expand the rich lore and cultures of Middle-earth, making it feel more real.

It starts in the rising action

Subplots are usually introduced during the main story’s rising action. In the Save the Cat beat sheet, the B story (aka subplot) is introduced in the 7th beat, about one fifth of the way into the story. Similarly, in the Three-Act structure, subplots tend to be introduced in the second act.

Some subplots are also resolved during the rising action, especially if they drive the main plot, like in the Romeo and Juliet example. However, some subplots continue into the falling action and beyond, particularly ones that explore relationships between characters. Jo March and Professor Bhaer’s romantic subplot, for instance, is not resolved until the dénouement of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women.

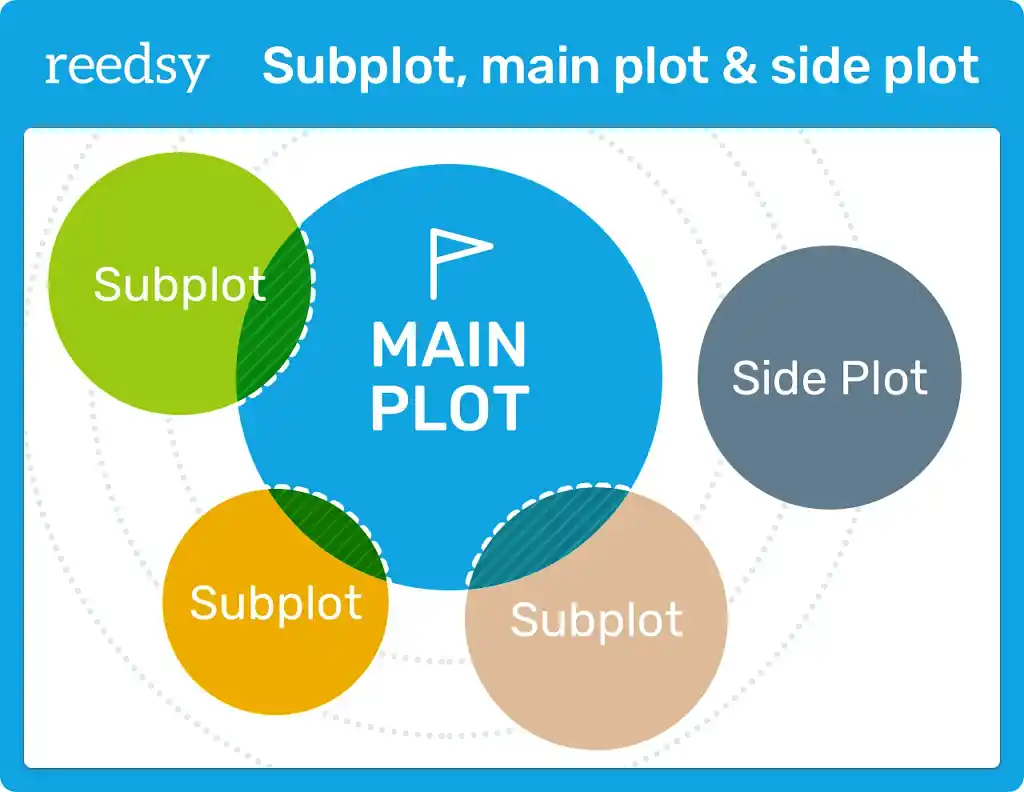

It’s not the same as a side plot

A subplot can sometimes be difficult to identify. You might hear “subplot” and “side plot” used interchangeably, but they’re not quite the same:

- A subplot always connects to the main story, influencing its events, characters, or themes.

- A side plot, on the other hand, can stand alone — it might be interesting, but it doesn’t really impact the main narrative.

You can think of it like a Venn diagram. All subplots have varying degrees of overlap with the main plot, but side plots do not intersect at all.

In Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince by J.K. Rowling, Harry’s private lessons with Dumbledore and the pensieve are a subplot, as they directly affect Harry’s understanding of how to defeat Voldemort. Meanwhile, Fred and George setting up their own joke shop in Diagon Alley is a side plot — fun and entertaining, but not critical to the main story of Harry versus Voldemort.

To distinguish between a side plot and a subplot, ask yourself: would the main events of the story be the same without it? If the answer is no, you’re looking at a subplot.

Now that we have seen what a subplot is and why it might be useful, it’s time to look at the different types of subplots.

7 common types of subplot (with examples)

We can broadly divide subplots into seven main types. Let’s explore each type, along with examples from classic and modern literature.

Romantic subplot

A romantic subplot follows (spoiler alert) two characters falling in love! This subplot is suited to any genre and can help make characters more believable and relatable, even if things don’t work out. (Not finding true love is relatable, too.)

Readers usually root for love, so a romantic subplot can keep your reader invested. It also shapes the characters’ actions in the main plot — whether the search for love spurs them on or blinds them so that they make bad decisions.

Example: Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

In Les Misérables, Marius and Cosette’s romantic subplot provides some lighter relief in the middle of quite heavy scenes featuring poverty, revolution, and death. It causes a new internal conflict, pulling Marius between his revolutionary ideals and his personal happiness. It also introduces a contrasting theme of hope, showing that love can endure even in the face of turmoil.

Platonic relationship subplot

It’s not just romantic relationships that can form valuable subplots. Other relationships with family or friends can also add layers to a character’s personality and show how they grow as a person. For example, a subplot in which a character makes friends with someone from a different religion could increase their tolerance and open-mindedness, while a subplot in which they repair their relationship with an estranged parent could improve their self-confidence and ability to trust.

Example: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck’s relationship with Jim, an escaped slave, is a subplot that contributes significantly to Huck’s moral development. As they journey together down the Mississippi River, Huck’s bond with Jim grows, leading him to reject the racist beliefs he’s been taught and rely more on his own instinctual feelings of right and wrong.

Nemesis subplot

A nemesis subplot shows a character’s personal growth through their run-ins with a nemesis or rival, also known as a foil character (which doesn’t have to be a “baddie” — instead, it could be a classmate or a partner’s ex). This kind of subplot often forces the protagonist to confront their weaknesses and challenges their attitude, for example by forcing them to concede that their nemesis is right or work on a team with them for the greater good.

Example: Percy Jackson & The Olympians by Rick Riordan

In Percy Jackson & The Olympians, Percy’s rivalry with Clarisse La Rue, the fierce daughter of Ares, challenges him to prove his worth. Clarisse sees him as weak, constantly pushing him into conflicts that force him to grow in skill and confidence. Eventually, Percy and Clarisse come to respect each other, showing how both of them grow to rise above petty rivalries and recognize that they are on the same team.

Foil subplot

A foil subplot differs from a nemesis subplot in that it depicts a character actively working against the protagonist’s success. Again, this could be the antagonist — but it doesn’t have to be. Instead, it could be that former ally who disagrees on the best way forward, or even a well-meaning third party who’s unaware of the main character’s plan and accidentally foils it. Either way, the purpose of this subplot is to create further obstacles for the protagonist to overcome, raising the stakes and increasing tension.

Example: The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo is determined to destroy the One Ring to prevent the dark lord Sauron from using its power to dominate the world. However, he’s stopped by another member of the fellowship: Boromir, who believes the Ring could be used as a weapon against Sauron and tries to take it from Frodo. This creates a clash of ideologies, where Boromir, who is otherwise a "good" character, acts in direct opposition to Frodo's mission.

Flashback subplot

A flashback subplot, which reveals past events that have a bearing on the present narrative, is good for creating suspense by gradually revealing information about a character’s past. These insights help the reader to understand their personality and motivations in the present day.

Example: The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

In Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner, flashbacks help us understand how Amir’s childhood choices have shaped him, putting his guilt and redemption arc into context. Each flashback adds emotional weight to his present struggles, allowing readers to fully grasp his motivations and the depth of his internal conflict.

Mirror subplot

Unlike most other types of subplot, a mirror subplot doesn’t impact the protagonist much. Instead, it runs in parallel to the main plot, sharing some of its themes or structure — but differing in some crucial way to reinforce themes or provide additional contrasting perspectives. A classic example of a mirror subplot is when another character faces the same problem as the protagonist, but reacts to it very differently.

Example: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

This is the case in Wolf Hall. Thomas More’s subplot mirrors the protagonist’s, Thomas Cromwell’s. Both characters serve King Henry VIII as he divorces Katherine of Aragon, creating political waves. However, while Cromwell adapts pragmatically for self-preservation, More stands by his Catholic faith and is ultimately martyred for it. More’s contrasting decision to choose principle over power adds an extra dimension to the novel’s themes of survival, morality, and loyalty.

Frame subplot

A frame subplot, which usually has no influence at all on the story’s characters, is yet another step removed. It sandwiches the main story, normally by following a narrator who is at best tangentially connected to the events of the plot. The subplot then depicts the narrator retelling the story for their own purposes and commentating on the tale, sometimes foreshadowing events or offering insights into the characters or themes.

Example: The Princess Bride by William Goldman

The Princess Bride features a frame subplot in which a fictionalized William Goldman narrates the story to his son, often interrupting the narrative with funny remarks and personal anecdotes. Goldman builds anticipation by referring to future events as “inconceivable” and uses the subplot to emphasize how life is unpredictable and death inevitable.

3 tips to write a compelling subplot

Of course, subplots can add incredible depth to a story, but they need to be well-executed to serve their purpose effectively! If you’re writing a story, here are three top tips to make effective use of subplots:

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

1. Make sure your subplot enhances the narrative

Don’t feel like you have to shoehorn subplots into your writing. If a subplot doesn’t strengthen the main narrative in some way, it’s at best a side plot — and at worst, irrelevant waffle. Many stories don’t need any subplots to be successful, like Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

It’s also important not to let an exciting subplot overshadow your primary story. If a subplot feels more interesting than the main plot, perhaps it’s time to rethink your plot structure.

2. Give it a beginning, middle, and end

A subplot needs its own beginning, middle, and end. You’ll usually want to return to the same subplot multiple times throughout the narrative. Just don’t forget to give it a resolution — unless you’ve made a conscious decision to leave the subplot on a cliffhanger, for example as a setup for a sequel.

In Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Charlotte Lucas’s marriage to Mr. Collins serves as a subplot that starts when she pragmatically accepts his proposal. As the story progresses, Elizabeth struggles with Charlotte’s decision, which challenges her own views on love and marriage. By the end, the subplot has been resolved: Charlotte has found her own form of contentment, and Elizabeth has grown in her understanding of social expectations and personal happiness.

3. Think about timing

The placement of a subplot is important. A subplot introduced too early can risk overloading the reader with too many details, while a subplot introduced too late can feel like an afterthought.

Don’t forget that the best subplots coincide with pivotal moments in the main plot (think back to our example of Romeo and Juliet). You might find it useful to work backwards: start with the change you want to see in your character, and then write a subplot that lets it happen.

Subplots aren’t just filler — they’re an opportunity to add richness and complexity to a story. Whether deepening characters, enhancing a world, or expanding on important themes, the right subplot can make all the difference.

Looking to improve your story structure? Our experienced book coaches and developmental editors can help make your story the best it can be.