Posted on Apr 02, 2021

In Medias Res: Definition, Usage, and Examples

Tom Bromley

Author, editor, tutor, and bestselling ghostwriter. Tom Bromley is the head of learning at Reedsy, where he has created their acclaimed course, 'How to Write a Novel.'

View profile →In writing, starting in medias res means beginning a story in the middle of the action and answering the reader's questions through flashbacks or dialogue. For example, a thriller that starts in medias res might open with the detective already on the trail of the killer.

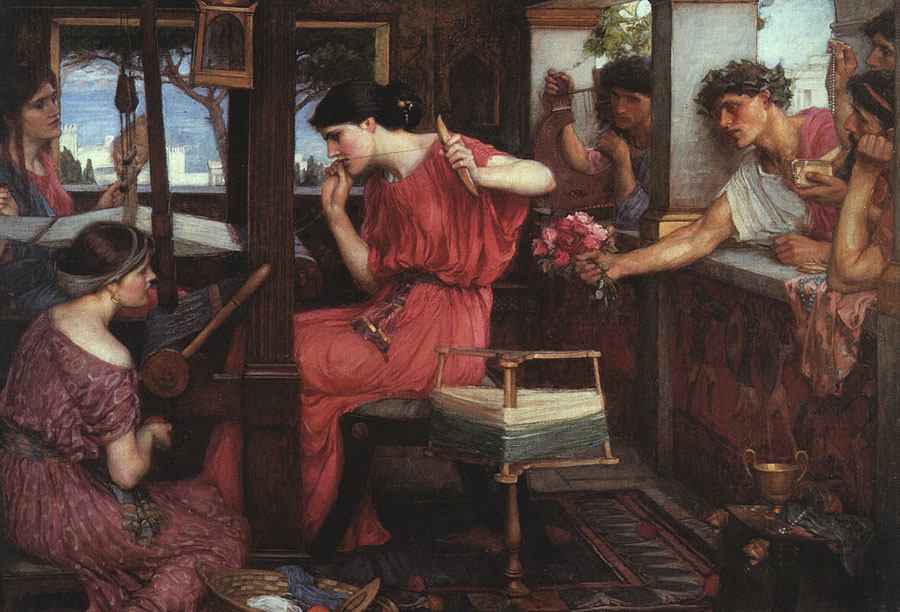

Notable examples include Homer’s epics the Iliad and the Odyssey, which Horace describes as starting not ab ovo (“from the egg”) but in medias res since both skip past the history and outbreak of the Trojan War. This literary device is — taking some liberties with Horace’s words — the storytelling equivalent of the chicken coming before the egg.

In this post, we’ll look at how in medias res can be used to tell a thrilling and captivating story, and how it has influenced the evolution of storytelling.

What does starting in medias res achieve?

There’s a common misconception that beginning in the middle of the ‘action’ stipulates car chases, explosions, and destruction, but it can be much more mundane than that. When you start in medias res, you trade detailed environment and character explanations for a more immediate effect: an in medias res scene does the golden rule of showing rather than telling. Essentially, you’re tinkering with the common structure, starting with something right in the middle of happening rather than the beginning of the story.

Q: What makes a compelling first chapter in a novel?

Suggested answer

The first chapter of any novel is so, so important. It's where the story is set up so that readers can get a taste of what they're in for over the next 8-12 hours. However, there is a multitude of elements that go into successful first chapters, and they must be expertly woven together to make it compelling. By the end of the first chapter, it comes down to one thing: if the reader isn't hooked, they likely won't continue. And they need three things to keep them interested.

- Curiosity

- Tension

- Emotion

The sooner these things become apparent in the pages, the better. Readers want to feel emotionally connected to the main character so that they can empathize with them, feel like they intimately know them, and root for them to reach their goal. They want to care about what happens to them. If there's tension, readers will worry about them and be curious about how it's going to play out. And when readers are curious, that means they're theorizing about what might happen. If they're theorizing, they're engaged in the story. Their brains feel like they're actively participating in figuring things out--and that's what makes them feel compelled to keep turning those pages.

My favourite novels aren't the ones that open with a beautiful sunrise or a description of the surroundings or backstory or having a character wake up. These are cliché in today's publishing landscape. Instead, they have opening lines or paragraphs that evoke such strong curiosity in me, something shocking or surprising or unexpected, that I'm hooked right from the start. These are the novels that hold my attention not just through the first chapter, but through all of them. The authors make sure there's curiosity, tension, and emotion present, along with other elements, such as a hint about the protagonist's internal conflict and flaws, an idea about goals and stakes, their desires, an imbalance of power, more showing than telling, etc. that contribute to my brain's need to feel engaged and interested.

So, it's not just about having all the elements that go into writing an exceptional novel. It's the art of weaving them all together in a style and voice that's intriguing and engaging from the very first page. Readers of fiction want to be entertained, so it's your job as the writer to make that promise and follow through with it by capturing their attention as soon as possible in the first chapter and not letting go until the very last page.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Starting with a strong opening line that is intriguing will help pull the reader into the narrative.

"Where is Papa going with that axe?" is the opening line of Charlotte's Web. We open with intrigue, and in the middle of the action of the story.

Then you want to have a strong build-up to the inciting incident, which should come at about 12,00-13,000 words into the story.

You want your main character to be likable and interesting to the reader.

You want to leave any backstory details for later on and keep the action of your opening scene continuous and going strong.

Then, if possible, you want to end this chapter with the promise of more "trouble" to come or an unanswered question regarding the trouble at hand, or at the very least, some ruffled feathers regarding your main character. There needs to be trouble brewing soon, and discomfort felt by your hero.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Here are some of the reasons why a writer would choose to start a story in medias res, illustrated by the most famous example of in medias res: The Odyssey.

It captures the reader’s attention

Horace notes how Homer’s choice to not begin ab ovo succeeds in capturing the reader’s attention from the get-go. There’s nothing that quite makes readers sit up in their reading chairs and pay attention like being confronted with the unexpected. Despite its long history in storytelling, in medias res continues to produce this effect by not giving readers the information they think they’ll get at the start of a story. Successful use of this device can thus hook your reader and get them invested in turning the pages.

Example: The hero of Troy, ten years later

Homer opens the Odyssey years after the Trojan War has ended. Odysseus is trying to make his way back home to Ithaca, where his son Telemachus is busy warding off his mother’s suitors. These would-be stepdads are threatening to take over Odysseus’s position as king and husband. With so much at stake, Homer hooks the audience from the very beginning and can develop several stories within the story.

It establishes a central question/mystery

Part of what is so fetching and attention-grabbing about an in medias res beginning is that it quickly establishes a central question or mystery — something that the reader is invested in solving. When you hold some of the information back, the reader’s mystery-solving neurons will start firing to fill in the gaps. Of course, the best way to fill those gaps is to keep reading. Writers can use this relationship between the text and the reader as a famous gun of Chekhov's. How? By taking full advantage of your readers’ curiosity as they scour the text for clues and context.

Example: What’s taking Odysseus so long?

In the Odyssey, the central question is why Odysseus still isn’t back on Ithaca, ten years after the Trojan War has ended. Through stories within the story, Homer allows Odysseus to explain himself and the obstacles he has faced, while also displaying his inordinate amount of cunning and bravery.

It can help create dramatic irony

Another major advantage of in medias res is that you can clue the reader into what will happen to the protagonist and the story but leave the characters fumbling in the dark. This creates a level of dramatic irony. Balancing the fine line between giving the plot away and showing just enough allows the reader to stay one step ahead of the characters. They know where they’re going, but not how they’ll get there.

Q: What is the biggest mistake writers make in their opening chapters?

Suggested answer

The biggest mistakes I see in the opening chapters of new authors are:

- Spending too much time on backstory that is not needed in the present moment or in the opening situation the book starts with. Any backstory information that is crucial to the story should be woven into the narrative as the story goes along or introduced after the initial inciting incident. The reader needs to know enough about the character to care about what happens to them and to begin rooting for them, but they don't need to know their entire life's story or all of the characters that occupy their world.

- Not providing enough information to give the story a sense of place, especially in stories that do not take place in the present day. In historical, sci-fi, and fantasy, there needs to be some time spent in world-building by placing descriptive sentences here and there in the opening. For instance, stating that someone is traveling in a carriage denotes a historical novel. Traveling at light speed in a spaceship evokes images of sci-fi and perhaps another planet or world. So be sure to place your characters in this new world right away.

- Not starting to move quickly enough into the inciting incident or the catalyst of the story, and spending too much time on non-consequential details like gardening, eating, riding a bike, brushing teeth, etc. There needs to be some type of action and some sort of trouble within the first 12,000 - 13,000 words. This is a good benchmark to shoot for as far as having your inciting incident occur by this point in the story.

You may have to try a few ways and experiment with different points in time as far as where your book needs to start.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Your first chapter has a lot of work to do. It needs to engage readers straight away, and by readers I mean everyone from a literary agent's assistant to a commissioning editor, a book marketer, or someone in a bookshop idly picking it up. That means something has to ignite in those first few thousand words, whether a plot, a question or a voice.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: Odysseus tells stories while someone moves in on his wife

The Odyssey establishes dramatic irony by informing the audience of what is happening on Ithaca and leaving Odysseus unaware. Though Odysseus’ ultimate goal is to return to his home island, he doesn’t know just how urgently he is needed there or what will meet him upon his return.

It creates tension

Ultimately, these effects all add up to one thing: in medias res is an excellent tool to create tense and dynamic writing in the 'rising action' part of any story. It’s the perfect way to pique someone’s curiosity and get them invested in the story — by leaving out essential details, the audience is left wondering ‘How did we get here?’ and ‘How will this end?’. The immediate sense of mystery, tension, and excitement created by starting the story in this way propels it forward, even in the more quiet parts of the novel — it’s no wonder authors have used this technique for so long.

Example: Will Odysseus prevail and manage to overcome the suitors?

Being one of the most well-known examples in literature, it would perhaps be a bit much to claim that these different effects create tension in the Odyssey. That ship has sailed. And yet, generation after generation of readers is left wondering if Odysseus will manage to protect his wife and kingdom on Ithaca. Will his bravery and cunning be his saving grace?

How to use in medias res

To enjoy the fruits of in medias res, you first need to strengthen your storytelling craft. A good beginning is only the first step towards a bestselling whole, so keep these tips close to your heart as you employ this literary device.

FREE RESOURCE

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

1. Plan your beginning, middle, and end

You’ve probably heard this tip before — and for good reasons. Everyone always says that planning is key when writing a novel, but that’s perhaps truer than ever when you’re using in medias res. Since these beginnings are supposed to be in the midst of things, it goes without saying that you have to first have a good idea of what those things are. You’ll want to know the beginning and end of your plot so you can efficiently unravel the context throughout your story. So, begin by establishing at least the following:

- The chronological order of your events

- The unique qualities of your main characters

- The main conflict — questions you want to ask and answer

- Any necessary subplots and how they fit into the main narrative.

Example: Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

This popular YA novel starts off with an introductory section in which a young woman, Bella, is being chased by someone or something. It’s clear that she’s in great peril but we don’t find out who’s chasing her and whether she will survive the chase until the story's climax.

Imagine sitting down and writing this prologue without a clue about any of the events that have led up to it. Though we can’t say for sure that Meyer sat down and planned Twilight using these bullet points, we can make an educated guess and say that she probably had a good idea of the plot, characters, and main conflict of the story before she put pen to paper. She probably knew that Bella will move to a small town with little to no sunshine, that she will meet an ashen figure by the name of Edward, and that Edward’s vampire identity will put Bella in grave danger. Without those basics, how could there even be a prologue?

2. Write out an emotional or pivotal scene

So, once you’ve planned out your narrative arc in chronological order and know at least the actual beginning, middle, and end of the plot, you should also have a good idea of what the climax will be or what you want your story to say about your characters and world. Knowing that it’s time to write an emotional or pivotal scene.

Q: What techniques can authors use to hook readers from the first page?

Suggested answer

Start with your main character doing something somewhere and start in the middle of the action. If there is a hurricane coming, have them board up the windows of their home. If they are dreading an upcoming test at school, have them look over their last test grades and worry that this next test won't be any different.

You want to avoid "talking heads." This is what publishers think when there is dialogue going on between characters, and because there is no sense of "place" or "setting", the story comes off as characters "talking in space." This is why you want the characters to be somewhere and do something in every new scene you draft, not just the opening.

Readers like to visualize the action in a book, even if the "action" is inward. So start off with a visual picture of your main character doing something, and this should hook readers.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I recall reading a memoir of a famous tennis player and he started it by plunging the reader into his experience of facing a relentless machine shooting balls across the net to him -- all the fatigue and pressure of trying to become a pro was encapsulated in the scene. Much more interesting than starting it with when and where he was born etc.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Some authors actually write a full draft of their story in chronological order, but that’s not strictly necessary. All you have to do is write a full scene and make sure that you know what caused that scene and how it will end — how it fits into the chronological story you’ve outlined. This will form the basis of your opening scene later and should also carry an emotional punch, be important for the plot, or pivotal for the protagonist to grab your future reader’s attention.

Example: Kill Bill Vol.1

Picture this Tarantino classic's opening scene: A woman in a blood-soaked wedding dress, breathing heavily and in obvious distress. Cowboy boots slowly approach and her fear visibly mounts. The wearer of the boots — Bill — wipes her face with a handkerchief. The bride pleads, telling Bill that she’s carrying his baby. But before she can finish, she is shot in the head. Nancy Sinatra's “Bang Bang” plays on the soundtrack as we cut to the title card: Kill Bill.

This opening quickly establishes the movie's mood and tone and brings up many of the questions we can expect from an in medias res beginning. ‘How did a wedding turn into a massacre?’ is possibly the most pressing one. This sets the tone for the revenge plot that ensues.

3. Enter late and leave early

When you’ve written an evocative scene in full, you’ve nailed down the substance of your dramatic start and can go on to the application part of the process. For a punchy and gripping beginning, keep things short! Remove any detail that explains why the scene is happening and how it ends (you’ll reveal these later). Entering the scene late and leaving it early is not only great for foreshadowing clues for the rest of the story, but is a powerful way to get the reader asking questions that will stay with them through the rest of the story:

- Who are the characters?

- What’s going on?

- When and where are we?

- How did we get here?

- What will happen next?

Q: Can I break traditional story structure rules and still write a good book?

Suggested answer

The quick answer to this is yes!

The longer answer is that, in order to break the rules of traditional story structure, you must first understand them. Authors who are successful at going completely outside of the 'norm' in storytelling and writing really know their stuff. They understand why the 'rules' are in place, and then they work hard to go against them in a meaningful, intentional, and acceptable way. If you look at experimental literary fiction, for example, you'll see a lot fewer examples than, say, the typical commercial fiction novel. In commercial fiction, there are certain expectations in terms of style, voice, tropes, structure, etc. Readers go to these types of novels to have their reading desires and expectations fulfilled. But that doesn't mean you can't surprise them every now and again.

The great thing about writing fiction is that you can do whatever you want--the sky is the limit. Structure, style, etc. can be played around with, but it must be exquisitely executed. And to achieve that, you must first know the rules like the back of your hand and master them.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking the traditional story structure is best done after you have a few books under your belt and are a seasoned author, especially if you are seeking a traditional publisher. There is enough risk for publishers to take a chance on a new author without the added risk of trying to push something that is out of the box. There are many people in the publishing chain of approval, and trying to sell the idea to the bulk of a publishing staff can be challenging if the author has no track record of sales to speak of.

When starting out, it really is a good idea to "play by the rules" if and when possible. That doesn't mean your book will not be "good" if you break the rules, but it's risky. Because the reality is that not all "good" books get book deals. This business is very subjective, and publishers run for-profit businesses, and they want and expect to make money on their books. Unfortunately, every decision regarding books that get chosen for publication is not based on artistic merit alone.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk

We open with a man named Tyler Durden sticking a gun down an unnamed narrator’s throat in a skyscraper that is about to explode. As readers, we’re late to the party and the stakes are already through the roof. We don’t know how the characters got to this point and we’re ushered along before we find out whether Durden pulls the trigger.

Who is Tyler Durden? Who is the narrator? Why does one want to kill the other? Why are they on a skyscraper? Is he going to pull the trigger?

As we flashback to the beginning of the story, these questions will pull the reader inexorably towards the novel’s twisty conclusion.

4. Write a killer first line

Now we’ve got the scene, we can zero in on the nitty-gritty details, like the first line. You want to pick a killer first line to act as your hook, line, and sinker. When using in medias res, a strong first line doesn’t only reel the reader in (the scene itself is probably compelling enough), but can also act as a signal which lets the reader know that they don’t have to understand the scene that’s about to unfold just yet. It sign-posts that there is a larger context that will be revealed all in due time. The first sentences below, for example, all allude to either a past or future to come.

Examples:

“Tyler got me a job as a waiter, after that Tyler's pushing a gun in my mouth and saying, the first step to eternal life is you have to die.”

— Fight Club, Chuck Palahniuk

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

— One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez

“In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself, in a dark wood, where the direct way was lost.”

— The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri

5. Decide on how to provide the missing context

With a killer opening line and a strong first scene, the audience will be on the edge of their seat, dying to know the information that you’ve deliberately left out. The rest of your story will be dedicated to slowly giving more and more context or answering the questions that you’ve made your readers ask. To do so, you can use literary devices like:

- Flashbacks: The protagonist and other characters think about the past and invite the reader into their memories.

- Dialogue: Two or more characters talk about and make references to the past.

- Time-jumps: The entire plot shifts backward or forwards and either continues chronologically or continues to jump in time.

Q: What are the signs that the middle of my story isn't working?

Suggested answer

People tend to rush through the middle because the beginning and ends is more exciting to focus on haha. We can often see signs of this if it feels as though there's either a lot of recap or constant going from scene to scene (this happened, then this, then this).

We still want tension and emotional moments in the middle; it's good to break up the transitions with these.

One more trick I suggest is asking yourself "What is the goal of this scene/this moment?" or "What am I hoping this does for the reader or plot?" We still need to be thinking of the internal and external motivations as we move through the middle chunk.

Val is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When there are no more problems to be solved or there is not enough conflict and tension in the middle to keep readers reading. There must be plenty of conflict and tension and the major problems of the story should not be resolved until the end of the book.

If there is no subplot and the pace slows. Another way is to have someone else look over your book and give you honest feedback on the weak areas that concern you.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Of course, you can combine these devices as you deem fit. You can even combine flashbacks to the past with references in speech with other devices and techniques, like having multiple plot lines or POVs, to tell your story. Say you’re writing a fantasy novel, which would entail a lot of worldbuilding — you can use multiple perspectives and time jumps to both unravel the context behind your opening scene and explore the realm. Or perhaps you’re writing a crime thriller, and you want to shed light on the mystery by having your detective extract bits of the backstory from witnesses and suspects through shrewd interrogations. The world is your oyster at this point.

Example: Big Little Lies (TV Show)

Someone has died during a school fundraiser in a suburban community. We don’t know who, why, or how. In a combination of police investigations and a time-jump to six months before the event, we get clues and puzzle pieces to fill in the missing context. Like peeling back the layers of an onion, we come closer and closer to the core of the problem and get a better understanding of big truths, hidden by many small lies. Circling back to the opening scene, these lies and relationships lead us to the answers to the questions of who died, why, and how.

Hopefully, with these tips and examples, you’ll feel better equipped to go out and explore how in medias can be used to add something a little bit extra to your own story. Don’t wait for the egg to hatch! 🐣