Guides •

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

The Hero's Journey: 12 Steps to a Classic Story Structure

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →The Hero's Journey is a story structure which follows a hero on their journey of growth and change. Typically, this adventure will have the hero starting out in their ordinary world, until they're forced out of their comfort zone to face challenges, gain insights, and return home transformed. From Theseus and the Minotaur to The Lion King, so many narratives follow this pattern that it’s become ingrained into our cultural DNA.

In this post, we'll show you how to make this classic plot structure work for you — and if you’re pressed for time, download our cheat sheet below for everything you need to know.

FREE RESOURCE

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your character's journey with our step-by-step template.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero's Journey, also known as the monomyth, is a story structure where a hero goes on a quest or adventure to achieve a goal, and has to overcome obstacles and fears, before ultimately returning home transformed.

Q: How can writers incorporate popular story models like The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat while maintaining originality and creativity in their writing?

Suggested answer

Saving the cat can come into play in many forms. At the end of the day, readers want to root for likable heroes. If you make your main character sympathetic in some way, that sort of ticks the "saving the cat" box off nicely.

A journey can comprise so many forms. It can be a literal journey Dorothy takes from Kansas to Oz and then back again in The Wizard of Oz, or it can be an inner journey of deciding to take charge of his life and not let others make his decisions for him, as we see with Macon Leary in the book The Accidental Tourist.

As long as your "save the cat" moment and "hero's journey" uses unique ideas that have not become cliché, you should be fine.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

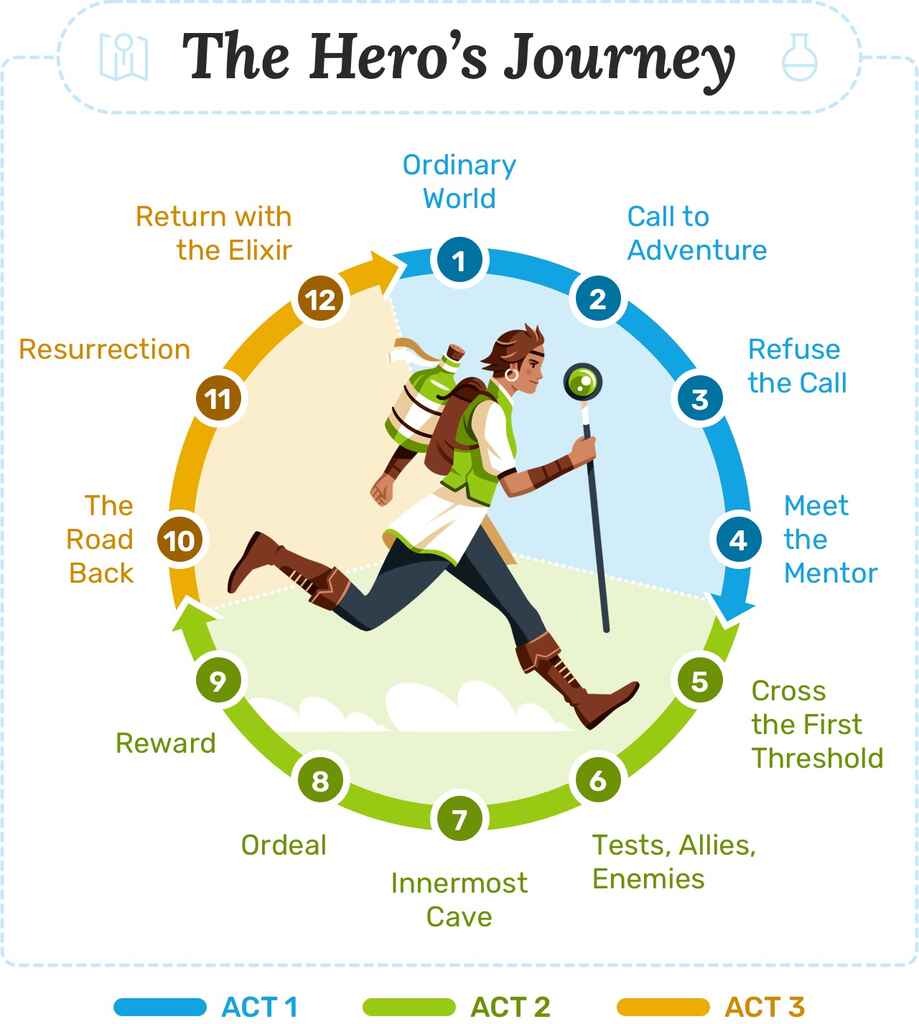

This narrative arc has been present in various forms across cultures for centuries, if not longer, but gained popularity through Joseph Campbell's mythology book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. While Campbell identified 17 story beats in his monomyth definition, this post will concentrate on a 12-step framework popularized in 2007 by screenwriter Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey.

The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey is a model for both plot points and character arc development: as the Hero traverses the world, they'll undergo inner and outer transformation at each stage of the journey. The 12 steps of the hero's journey are:

- The Ordinary World: We meet our hero.

- Call to Adventure: Will they meet the challenge?

- Refusal of the Call: They resist the adventure.

- Meeting the Mentor: A teacher arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold: The hero leaves their comfort zone.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies: Making friends and facing roadblocks.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: Getting closer to our goal.

- Ordeal: The hero’s biggest test yet!

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): Light at the end of the tunnel

- The Road Back: We aren’t safe yet.

- Resurrection: The final hurdle is reached.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero heads home, triumphant.

Believe it or not, this story structure also applies across mediums and genres. Let's dive into it!

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

1. Ordinary World

In which we meet our Hero.

The journey has yet to start. Before our Hero discovers a strange new world, we must first understand the status quo: their ordinary, mundane reality.

It’s up to this opening leg to set the stage, introducing the Hero to readers. Importantly, it lets readers identify with the Hero as a “normal” person in a “normal” setting, before the journey begins.

2. Call to Adventure

In which an adventure starts.

The call to adventure is all about booting the Hero out of their comfort zone. In this stage, they are generally confronted with a problem or challenge they can't ignore. This catalyst can take many forms, as Campbell points out in Hero with a Thousand Faces. The Hero can, for instance:

- Decide to go forth of their own volition;

- Theseus upon arriving in Athens.

- Be sent abroad by a benign or malignant agent;

- Odysseus setting off on his ship in The Odyssey.

- Stumble upon the adventure as a result of a mere blunder;

- Dorothy when she’s swept up in a tornado in The Wizard of Oz.

- Be casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man.

- Elliot in E.T. upon discovering a lost alien in the tool shed.

The stakes of the adventure and the Hero's goals become clear. The only question: will he rise to the challenge?

3. Refusal of the Call

In which the Hero digs in their feet.

Great, so the Hero’s received their summons. Now they’re all set to be whisked off to defeat evil, right?

Not so fast. The Hero might first refuse the call to action. It’s risky and there are perils — like spiders, trolls, or perhaps a creepy uncle waiting back at Pride Rock. It’s enough to give anyone pause.

In Star Wars, for instance, Luke Skywalker initially refuses to join Obi-Wan on his mission to rescue the princess. It’s only when he discovers that his aunt and uncle have been killed by stormtroopers that he changes his mind.

Q: Can I break traditional story structure rules and still write a good book?

Suggested answer

The quick answer to this is yes!

The longer answer is that, in order to break the rules of traditional story structure, you must first understand them. Authors who are successful at going completely outside of the 'norm' in storytelling and writing really know their stuff. They understand why the 'rules' are in place, and then they work hard to go against them in a meaningful, intentional, and acceptable way. If you look at experimental literary fiction, for example, you'll see a lot fewer examples than, say, the typical commercial fiction novel. In commercial fiction, there are certain expectations in terms of style, voice, tropes, structure, etc. Readers go to these types of novels to have their reading desires and expectations fulfilled. But that doesn't mean you can't surprise them every now and again.

The great thing about writing fiction is that you can do whatever you want--the sky is the limit. Structure, style, etc. can be played around with, but it must be exquisitely executed. And to achieve that, you must first know the rules like the back of your hand and master them.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking the traditional story structure is best done after you have a few books under your belt and are a seasoned author, especially if you are seeking a traditional publisher. There is enough risk for publishers to take a chance on a new author without the added risk of trying to push something that is out of the box. There are many people in the publishing chain of approval, and trying to sell the idea to the bulk of a publishing staff can be challenging if the author has no track record of sales to speak of.

When starting out, it really is a good idea to "play by the rules" if and when possible. That doesn't mean your book will not be "good" if you break the rules, but it's risky. Because the reality is that not all "good" books get book deals. This business is very subjective, and publishers run for-profit businesses, and they want and expect to make money on their books. Unfortunately, every decision regarding books that get chosen for publication is not based on artistic merit alone.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

4. Meeting the Mentor

In which the Hero acquires a personal trainer.

The Hero's decided to go on the adventure — but they’re not ready to spread their wings yet. They're much too inexperienced at this point and we don't want them to do a fabulous belly-flop off the cliff.

Enter the mentor: someone who helps the Hero, so that they don't make a total fool of themselves (or get themselves killed). The mentor provides practical training, profound wisdom, a kick up the posterior, or something abstract like grit and self-confidence.

Wise old wizards seem to like being mentors. But mentors take many forms, from witches to hermits and suburban karate instructors. They might literally give weapons to prepare for the trials ahead, like Q in the James Bond series. Or perhaps the mentor is an object, such as a map. In all cases, they prepare the Hero for the next step.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

In which the Hero enters the other world in earnest.

Now the Hero is ready — and committed — to the journey. This marks the end of the Departure stage and is when the adventure really kicks into the next gear. As Vogler writes: “This is the moment that the balloon goes up, the ship sails, the romance begins, the wagon gets rolling.”

From this point on, there’s no turning back.

Like our Hero, you should think of this stage as a checkpoint for your story. Pause and re-assess your bearings before you continue into unfamiliar territory. Have you:

- Launched the central conflict? If not, here’s a post on types of conflict to help you out.

- Established the theme of your book? If not, check out this post that’s all about creating theme and motifs.

- Made headway into your character development? If not, this author-approved template may be useful:

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

In which the Hero faces new challenges and gets a squad.

When we step into the Special World, we notice a definite shift. The Hero might be discombobulated by this unfamiliar reality and its new rules. This is generally one of the longest stages in the story, as our protagonist gets to grips with this new world.

This makes a prime hunting ground for the series of tests to pass! Luckily, there are many ways for the Hero to get into trouble:

- In Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle, Spencer, Bethany, “Fridge,” and Martha get off to a bad start when they bump into a herd of bloodthirsty hippos.

- In his first few months at Hogwarts, Harry Potter manages to fight a troll, almost fall from a broomstick and die, and get horribly lost in the Forbidden Forest.

- Marlin and Dory encounter three “reformed” sharks, get shocked by jellyfish, and are swallowed by a blue whale en route to finding Nemo.

This stage often expands the cast of characters. Once the protagonist is in the Special World, he will meet allies and enemies — or foes that turn out to be friends and vice versa. He will learn a new set of rules from them. Saloons and seedy bars are popular places for these transactions, as Vogler points out (so long as the Hero survives them).

Q: What is the 'saggy middle' in storytelling, and how do I fix it?

Suggested answer

A 'saggy middle' occurs when a story loses momentum, tension, and trajectory right around the midpoint of the story. A story can lose it's steam (and with it, a reader's interest) when character arcs stall, plots become muddled and messy, and subplots abound with no sense of direction. Stories can also sag if they fill pages with descriptive information that does little to engage the characters or further the story arc.

But never fear! This is a very fixable problem. First, think about the ideas at the heart of your story. What story do you want to tell? What lies at its core?

With that in mind, review the midsection of your story with an eye to the issues described above. Once you identify your problem areas, you can set about rewriting with a goal of increasing the tension by increasing the stakes for your characters, adding new conflicts/problems for characters to explore, cutting excess descriptions and sections that over-explain character motivations/backgrounds/actions, and tightening sections that do little to further the core plot that drives the story.

Erin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I tend to see saggy middles show up when authors are adhereing to a strick timeline of events, rather than sharing scenes that pull the plot forward. For example, I edit a lot of middle grade fiction and a saggy middle might include multiple chapters that open with the protagonist waking up and close with the protagonist going to bed. Or going to school, then getting home after. Readers don't need the day-by-day minutia to get from one scene to the next.

Instead, focus on what will pull your plot forward, and think of your middle as scenes rather than a timeline that gets you from point A to point B.

I usually suggest that authors step away from the manuscript and instead write scenes, even if out of order, that they need for their story to make sense. When finished, they can line them up in order, and then fill in the blanks for a much faster-paced and cohesive middle. Even if you don't have a saggy middle, this is an effective practice for planning and plotting purposes.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The 'saggy middle' of a story is the part of the story where the inciting incident - or the problem in the story - has already happened, but the ending, or climax and resolution, is nowhere in sight. It really does fall in the middle of the story.

There are several ways to handle this issue:

*Use a subplot with the main character or a secondary character that will still need its own resolution and will bring in another layer of trouble for your character[s]. In The Wizard of Oz, each of Dorothy's three friends suddenly has their own problems. The scarecrow loses his stuffing, for instance, so the storyline shifts for a bit from Dorothy's desire to get back to Kansas - her hero's journey and the through line of the book - and takes a slight turn to focus on the scarecrow and friends before turning back to Dorothy's main plot line again of getting home.

*Raise the stakes - create even more trouble for your character and/or make the result[s] of the trouble even more dire. In the book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, first, Mrs. Morris the cat is sent to the hospital, then humans that are Harry's friends, then finally, Ginny is in trouble, who will end up being Harry's love interest. So the stakes and problems keep building all the way through the book until the final climactic scene.

*Use what is called a 'midpoint reversal': This is where the character changes his mind about the issue and is not opposed to it any longer. In the movie "Tootsie", at first, Michael does not want to pretend to be a woman to get work, but by the middle, he loves the idea of pretending to be a woman and wants to take things even further, which causes friction between Michael and his agent. So more trouble occurs because of this mindset reversal, which then leads the book to its satisfying conclusion.

You don't have to use all of these techniques, but try one out in the middle of your book, and see which one works best for your own story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

In which the Hero gets closer to his goal.

This isn’t a physical cave. Instead, the “inmost cave” refers to the most dangerous spot in the other realm — whether that’s the villain’s chambers, the lair of the fearsome dragon, or the Death Star. Almost always, it is where the ultimate goal of the quest is located.

Note that the protagonist hasn’t entered the Inmost Cave just yet. This stage is all about the approach to it. It covers all the prep work that's needed in order to defeat the villain.

🧠 Enjoying learning about The Hero's Journey?

Join other writers in our Discord community to discuss structure and storytelling.

8. Ordeal

In which the Hero faces his biggest test of all thus far.

Of all the tests the Hero has faced, none have made them hit rock bottom — until now. Vogler describes this phase as a “black moment.” Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” Both indicate some grim news for the Hero.

The protagonist must now confront their greatest fear. If they survive it, they will emerge transformed. This is a critical moment in the story, as Vogler explains that it will “inform every decision that the Hero makes from this point forward.”

The Ordeal is sometimes not the climax of the story. There’s more to come. But you can think of it as the main event of the second act — the one in which the Hero actually earns the title of “Hero.”

Q: How can authors effectively build tension leading up to the climax?

Suggested answer

Well, the main method is to up the stakes as you go along. The more it matters emotionally to the characters and externally to their circumstances and the world around them, the more important that climax becomes. Every time you increase the stakes, the anticipation of readers goes up surrounding the climax and what might result. The final confrontation between hero(es) and villain becomes and edge-of-the-seat affair.

If you struggle with this, the technique I recommend is to examine the plot questions asked and answered. All plots are effectively a series of questions asked and answered. When you ask and how soon you answer is part of building tensions. Some questions carry over several scenes, some are answered right away. Some last whole chapters or several chapters. Some are asked at the beginning and not answered until the end, like the main driving core quest question of will good conquer evil? Will the protagonist get what he or she wants or needs? Will the villain prevail?

Make sure you are answering the questions you ask in appropriate places. Yes, you may want to set up a sequel and leave a few things hanging but the trick is to pick the right questions. The rest need to be answered, and figuring out which questions depend upon that climax and asking more and more of them as you lead up to it is a really great way to increase suspense and anticipation and lend that sense of urgency to the climax that keeps readers turning pages and dying to know what happens.

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Stakes need to be continually raised as the story builds to a climax. The problem[s] should be getting more and more difficult until the climax is reached.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Subtle foreshadowing is a solid way to build tension. Hinting at what's to come can prime the reader for the climax without revealing exactly what's coming—just that something is coming.

Well-written, lower-level conflicts between characters is another effective tool to build tension: short arguments, occasional emotional blow-ups, etc. These are, in effect, a kind of foreshadowing themselves, setting the reader up for the finale, whatever it may be.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

In which the Hero sees light at the end of the tunnel.

Our Hero’s been through a lot. However, the fruits of their labor are now at hand — if they can just reach out and grab them! The “reward” is the object or knowledge the Hero has fought throughout the entire journey to hold.

Once the protagonist has it in their possession, it generally has greater ramifications for the story. Vogler offers a few examples of it in action:

- Luke rescues Princess Leia and captures the plans of the Death Star — keys to defeating Darth Vader.

- Dorothy escapes from the Wicked Witch’s castle with the broomstick and the ruby slippers — keys to getting back home.

10. The Road Back

In which the light at the end of the tunnel might be a little further than the Hero thought.

The story's not over just yet, as this phase marks the beginning of Act Three. Now that he's seized the reward, the Hero tries to return to the Ordinary World, but more dangers (inconveniently) arise on the road back from the Inmost Cave.

More precisely, the Hero must deal with the consequences and aftermath of the previous act: the dragon, enraged by the Hero who’s just stolen a treasure from under his nose, starts the hunt. Or perhaps the opposing army gathers to pursue the Hero across a crowded battlefield. All further obstacles for the Hero, who must face them down before they can return home.

11. Resurrection

In which the last test is met.

Here is the true climax of the story. Everything that happened prior to this stage culminates in a crowning test for the Hero, as the Dark Side gets one last chance to triumph over the Hero.

Vogler refers to this as a “final exam” for the Hero — they must be “tested once more to see if they have really learned the lessons of the Ordeal.” It’s in this Final Battle that the protagonist goes through one more “resurrection.” As a result, this is where you’ll get most of your miraculous near-death escapes, à la James Bond's dashing deliverances. If the Hero survives, they can start looking forward to a sweet ending.

Q: Does a protagonist have to change over the course of their story?

Suggested answer

Great question! And as with so many answers when it comes to writing fiction, the answer is 'yes and no'. Let me elaborate...

Sometimes, a change in a character and how it happens is the entire point of a story. Look at 'A Christmas Carol' by Charles Dickens, for example: Scrooge must look into his past and understand how his life has brought him to this point. For him, if he doesn't change, he will die a lonely and unmourned death. For us, if he doesn't change, then all we really have is a book about a man shouting at Christmas.

And then sometimes there is a Katniss Everdeen. Her qualities of bravery and knowing what's right are there from the start - she wouldn't substitute for her sister otherwise. Those characteristics remain strong throughout. The change in the Hunger Games books are often about the changes Katniss brings to the world around her; her main job in the narrative is as an agent of change, as someone who is unafraid to stand up for what's right. We often see this in superheroes.

I'm also thinking about Harry Potter, who doesn't so much change as have knowledge revealed to him that changes the way he sees himself. Yes, he gains skills and knowledge as the books progress, but he is (literally) marked to be who he is from the beginning. The change here is in his understanding of who and what he is, and what happened to him and his parents - something that the reader discovers along with him.

So I'd say that there always has to be change - otherwise, why would we read a book at all?

And change will definitely occur around the protagonist.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that the character begins as 'a', goes through 'b' and becomes 'c'. This is what makes fiction so interesting, to read and to write.

Stephanie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. But in most cases, it's probably a good idea.

This criticism ("protagonist needs development/arc/change") is often shorthand for "this story doesn't have much craft to it" or "there's no arc to this thing." If the protagonist has no arc, good chance the story doesn't, either—but this isn't a hard-and-fast judgment.

The better question to ask is whether your protagonist should change. If not, you should have a firm idea why not, and so should your reader by the end. What would the character's not changing say, mean, or do? Is it a tale where everyone knows the protagonist needs to change, but he doesn't? Does he suffer the consequences? Get away with it? And so on.

Unless you can articulate why your character shouldn't change, then your editor is probably right: change would help the story along. But before you get rewriting, decide how this change will advance the story, what effects it will have.

In other words: Don't just change a character arc because an editor said you should. Change it because the story will be stronger for it.

Joey is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This is what is usually expected, especially in coming-of-age stories for teens. However, in some cases, the point of the story might be that the main character does NOT change. And if this scenario works best for the story you are trying to tell, then the protagonist does not have to change.

While growth in the protagonist by the end of the story is the "norm" for most books, sometimes the growth comes from getting what they wanted at the beginning. There are many ways for "growth" to occur. Whichever path is chosen must make sense for your story and feel organic to the narrative, not forced.

Example of a "stuck" adult character that doesn't change:

Archie Bunker from the TV show All in the Family - always a cynic and pessimist

Example of an adult character who is "stuck" at the outset, but grows by the end of the story:

Macon Leary from The Accidental Tourist - becomes "unstuck" and more independent

So, you have to do what works for your story and makes sense in the overall plot scheme.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

As they say, "change is the only evidence of life." So as a rough, general rule, it's a good idea to have character development.

As well as being an editor, I'm a screenwriter, and protagonist change is often stressed as essential in films to keep an audience interested.

But it depends on the type of story and character. If a character is interesting enough, and the point of the story includes that they don't change, then don't force them to.

There are no infallible rules about storytelling.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

12. Return with the Elixir

In which our Hero has a triumphant homecoming.

Finally, the Hero gets to return home. However, they go back a different person than when they started out: they’ve grown and matured as a result of the journey they’ve taken.

But we’ve got to see them bring home the bacon, right? That’s why the protagonist must return with the “Elixir,” or the prize won during the journey, whether that’s an object or knowledge and insight gained.

Of course, it’s possible for a story to end on an Elixir-less note — but then the Hero would be doomed to repeat the entire adventure.

Examples of The Hero’s Journey in Action

To better understand this story template beyond the typical sword-and-sorcery genre, let's analyze three examples, from both screenplay and literature, and examine how they implement each of the twelve steps.

Rocky

The 1976 film Rocky is acclaimed as one of the most iconic sports films because of Stallone’s performance and the heroic journey his character embarks on.

- Ordinary World. Rocky Balboa is a mediocre boxer and loan collector — just doing his best to live day-to-day in a poor part of Philadelphia.

- Call to Adventure. Heavyweight champ Apollo Creed decides to make a big fight interesting by giving a no-name loser a chance to challenge him. That loser: Rocky Balboa.

- Refusal of the Call. Rocky says, “Thanks, but no thanks,” given that he has no trainer and is incredibly out of shape.

- Meeting the Mentor. In steps former boxer Mickey “Mighty Mick” Goldmill, who sees potential in Rocky and starts training him physically and mentally for the fight.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Rocky crosses the threshold of no return when he accepts the fight on live TV, and 一 in parallel 一 when he crosses the threshold into his love interest Adrian’s house and asks her out on a date.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Rocky continues to try and win Adrian over and maintains a dubious friendship with her brother, Paulie, who provides him with raw meat to train with.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The Inmost Cave in Rocky is Rocky’s own mind. He fears that he’ll never amount to anything — something that he reveals when he butts heads with his trainer, Mickey, in his apartment.

- Ordeal. The start of the training montage marks the beginning of Rocky’s Ordeal. He pushes through it until he glimpses hope ahead while running up the museum steps.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Rocky's reward is the restoration of his self-belief, as he recognizes he can try to “go the distance” with Apollo Creed and prove he's more than "just another bum from the neighborhood."

- The Road Back. On New Year's Day, the fight takes place. Rocky capitalizes on Creed's overconfidence to start strong, yet Apollo makes a comeback, resulting in a balanced match.

- Resurrection. The fight inflicts multiple injuries and pushes both men to the brink of exhaustion, with Rocky being knocked down numerous times. But he consistently rises to his feet, enduring through 15 grueling rounds.

- Return with the Elixir. Rocky loses the fight — but it doesn’t matter. He’s won back his confidence and he’s got Adrian, who tells him that she loves him.

Moving outside of the ring, let’s see how this story structure holds on a completely different planet and with a character in complete isolation.

The Martian

In Andy Weir’s bestselling novel (better known for its big screen adaptation) we follow astronaut Mark Watney as he endures the challenges of surviving on Mars and working out a way to get back home.

- The Ordinary World. Botanist Mark and other astronauts are on a mission on Mars to study the planet and gather samples. They live harmoniously in a structure known as "the Hab.”

- Call to Adventure. The mission is scrapped due to a violent dust storm. As they rush to launch, Mark is flung out of sight and the team believes him to be dead. He is, however, very much alive — stranded on Mars with no way of communicating with anyone back home.

- Refusal of the Call. With limited supplies and grim odds of survival, Mark concludes that he will likely perish on the desolate planet.

- Meeting the Mentor. Thanks to his resourcefulness and scientific knowledge he starts to figure out how to survive until the next Mars mission arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Mark crosses the mental threshold of even trying to survive 一 he successfully creates a greenhouse to cultivate a potato crop, creating a food supply that will last long enough.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Loneliness and other difficulties test his spirit, pushing him to establish contact with Earth and the people at NASA, who devise a plan to help.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. Mark faces starvation once again after an explosion destroys his potato crop.

- Ordeal. A NASA rocket destined to deliver supplies to Mark disintegrates after liftoff and all hope seems lost.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Mark’s efforts to survive are rewarded with a new possibility to leave the planet. His team 一 now aware that he’s alive 一 defies orders from NASA and heads back to Mars to rescue their comrade.

- The Road Back. Executing the new plan is immensely difficult 一 Mark has to travel far to locate the spaceship for his escape, and almost dies along the way.

- Resurrection. Mark is unable to get close enough to his teammates' ship but finds a way to propel himself in empty space towards them, and gets aboard safely.

- Return with the Elixir. Now a survival instructor for aspiring astronauts, Mark teaches students that space is indifferent and that survival hinges on solving one problem after another, as well as the importance of other people’s help.

Coming back to Earth, let’s now examine a heroine’s journey through the wilderness of the Pacific Crest Trail and her… humanity.

Wild

The memoir Wild narrates the three-month-long hiking adventure of Cheryl Strayed across the Pacific coast, as she grapples with her turbulent past and rediscovers her inner strength.

- The Ordinary World. Cheryl shares her strong bond with her mother who was her strength during a tough childhood with an abusive father.

- Call to Adventure. As her mother succumbs to lung cancer, Cheryl faces the heart-wrenching reality to confront life's challenges on her own.

- Refusal of the Call. Cheryl spirals down into a destructive path of substance abuse and infidelity, which leads to hit rock bottom with a divorce and unwanted pregnancy.

- Meeting the Mentor. Her best friend Lisa supports her during her darkest time. One day she notices the Pacific Trail guidebook, which gives her hope to find her way back to her inner strength.

- Crossing the First Threshold. She quits her job, sells her belongings, and visits her mother’s grave before traveling to Mojave, where the trek begins.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Cheryl is tested by her heavy bag, blisters, rattlesnakes, and exhaustion, but many strangers help her along the trail with a warm meal or hiking tips.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. As Cheryl goes through particularly tough and snowy parts of the trail her emotional baggage starts to catch up with her.

- Ordeal. She inadvertently drops one of her shoes off a cliff, and the incident unearths the helplessness she's been evading since her mother's passing.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Cheryl soldiers on, trekking an impressive 50 miles in duct-taped sandals before finally securing a new pair of shoes. This small victory amplifies her self-confidence.

- The Road Back. On the last stretch, she battles thirst, sketchy hunters, and a storm, but more importantly, she revisits her most poignant and painful memories.

- Resurrection. Cheryl forgives herself for damaging her marriage and her sense of worth, owning up to her mistakes. A pivotal moment happens at Crater Lake, where she lets go of her frustration at her mother for passing away.

- Return with the Elixir. Cheryl reaches the Bridge of the Gods and completes the trail. She has found her inner strength and determination for life's next steps.

There are countless other stories that could align with this template, but it's not always the perfect fit. So, let's look into when authors should consider it or not.

When should writers use The Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is just one way to outline a novel and dissect a plot. For more longstanding theories on the topic, you can go here to read about the ever-popular Three-Act Structure, here to discover Dan Harmon's Story Circle, and here to learn about three more prevalent structures.

Q: What is the single most important piece of advice for first-time novelists?

Suggested answer

Write the story you want to write, need to write--and want to read. Don't think about or worry about market trends, or how you will position your book on the market, or writing a book that will blow up on BookTok. A novel is a marathon, and in order to see it all the way through, you have to love your story (you can dislike some of your own characters of course, but you need to be deeply passionate about the overall story you are telling). In practical terms, by the time you write, revise, and publish your novel, it's likely that overall publishing trends will have shifted anyway. Write the book you want to write--things like what readers want, what publishers want, what agents want, can come later!

Kristen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Read many books in your genre and look for why you like that particular book or don't like it. Get a feel for what works and what doesn't. Try to read books that sold well and were published in the last 5-10 years. Publishing norms change and styles change with time.

For instance, in the past, much time was spent setting up the story, and many opening paragraphs may have been spent describing the scenery and visual elements. While those elements are still important, modern books move at a much faster pace and spend less time on these elements by using sentences of description woven into the narrative rather than information dumps and blocks of long description that can slow the pace.

So, reading current books in your genre is the best way to learn writing methods yourself.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

So when is it best to use the Hero’s Journey? There are a couple of circumstances which might make this a good choice.

When you need more specific story guidance than simple structures can offer

Simply put, the Hero’s Journey structure is far more detailed and closely defined than other story structure theories. If you want a fairly specific framework for your work than a thee-act structure, the Hero’s Journey can be a great place to start.

Of course, rules are made to be broken. There’s plenty of room to play within the confines of the Hero’s Journey, despite it appearing fairly prescriptive at first glance. Do you want to experiment with an abbreviated “Resurrection” stage, as J.K. Rowling did in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone? Are you more interested in exploring the journey of an anti-hero? It’s all possible.

Once you understand the basics of this universal story structure, you can use and bend it in ways that disrupt reader expectations.

Need more help developing your book? Try this template on for size:

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

When your focus is on a single protagonist

No matter how sprawling or epic the world you’re writing is, if your story is, at its core, focused on a single character’s journey, then this is a good story structure for you. It’s kind of in the name! If you’re dealing with an entire ensemble, the Hero’s Journey may not give you the scope to explore all of your characters’ plots and subplot — a broader three-act structure may give you more freedom to weave a greater number story threads.

✍️

Which story structure is right for you?

Take this quiz and we'll match your story to a structure in minutes!

Whether you're a reader or writer, we hope our guide has helped you understand this universal story arc. Want to know more about story structure? We explain 6 more in our guide — read on!

6 responses

PJ Reece says:

25/07/2018 – 19:41

Nice vid, good intro to story structure. Typically, though, the 'hero's journey' misses the all-important point of the Act II crisis. There, where the hero faces his/her/its existential crisis, they must DIE. The old character is largely destroyed -- which is the absolute pre-condition to 'waking up' to what must be done. It's not more clever thinking; it's not thinking at all. Its SEEING. So many writing texts miss this point. It's tantamount to a religions experience, and nobody grows up without it. STORY STRUCTURE TO DIE FOR examines this dramatic necessity.

↪️ C.T. Cheek replied:

13/11/2019 – 21:01

Okay, but wouldn't the Act II crisis find itself in the Ordeal? The Hero is tested and arguably looses his/her/its past-self for the new one. Typically, the Hero is not fully "reborn" until the Resurrection, in which they defeat the hypothetical dragon and overcome the conflict of the story. It's kind of this process of rebirth beginning in the earlier sections of the Hero's Journey and ending in the Resurrection and affirmed in the Return with the Elixir.

Lexi Mize says:

25/07/2018 – 22:33

Great article. Odd how one can take nearly every story and somewhat plug it into such a pattern.

Bailey Koch says:

11/06/2019 – 02:16

This was totally lit fam!!!!

↪️ Bailey Koch replied:

11/09/2019 – 03:46

where is my dad?

Frank says:

12/04/2020 – 12:40

Great article, thanks! :) But Vogler didn't expand Campbell's theory. Campbell had seventeen stages, not twelve.