Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

The Fichtean Curve: A Story in Crisis

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →The Fichtean Curve — despite sounding rather scholarly — is a narrative structure beloved by writers of mystery and the pacy pulp fiction found in '60s magazines. Fleshed out in John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, it proposes storytelling by way of episodic events, which gradually build up to a grand, climactic crisis.

To understand the structure in a practical sense (and how it might be used by writers today) let’s delve into it some more. We’ll be mapping the structure onto John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, to explore its components in detail.

What is the Fichtean curve?

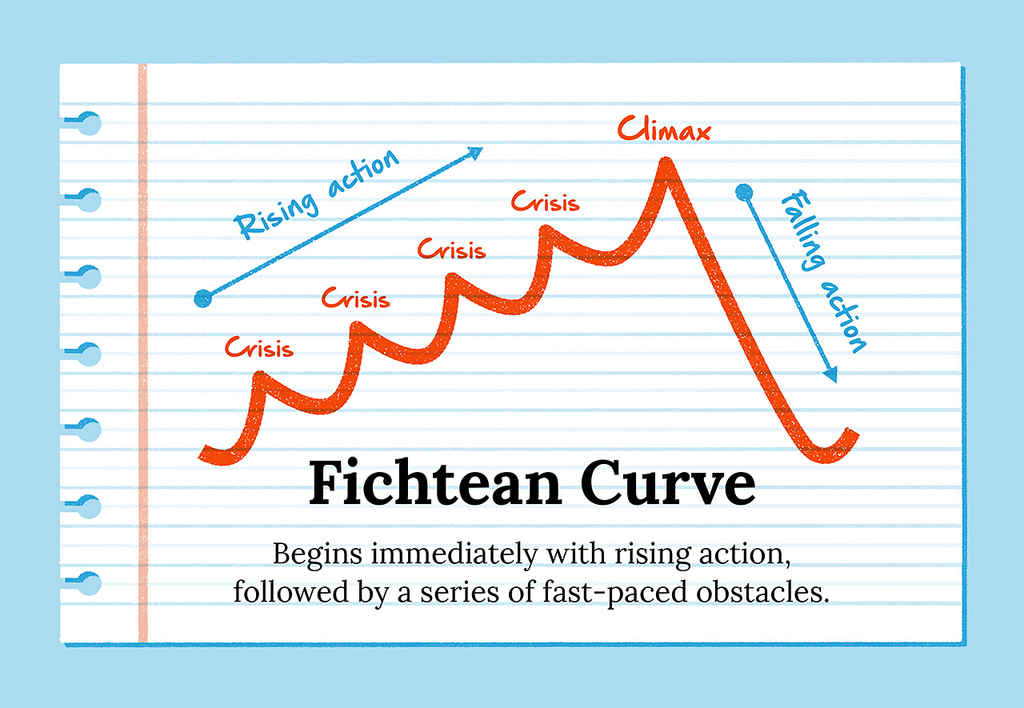

The Fichtean curve is split into three parts:

- Rising Action.

- Climax.

- Falling Action

Instead of a lengthy setup that thoroughly establishes our protagonist and the world of the story, it encourages the writer to enter the rising action as soon as possible — getting the show on the road posthaste. The first two-thirds of the story will encompass this rising action — a series of increasingly troubling crises. Any necessary context and character development should be interwoven with this action as the plot progresses.

The story will reach a climax in a final, larger crisis: an event that could be either catastrophic or redeeming for the protagonist. Either way, it drastically changes the course of the story and triggers a final period of falling action. Here, earlier plot points are tied up, and the story will be resolved in some way.

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

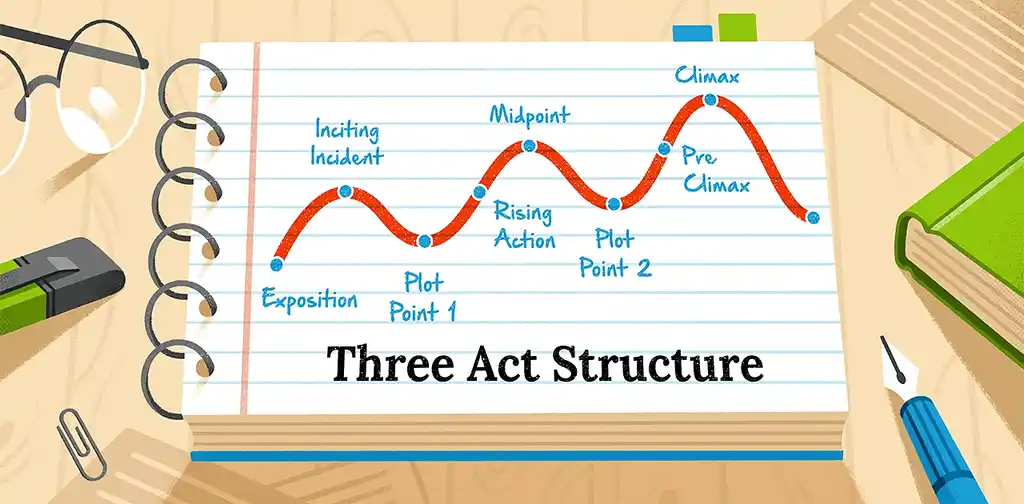

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

It's one thing after another

For many writers, the Fichtean curve will feel like a natural extension of how they intuitively tell stories — as a series of escalating mishaps or triumphs. It’s a simple formula that doesn’t demand over-the-top theatrics to keep its pace; rather, smaller episodes sustain a frisson of drama throughout. It works well for linear and non-linear plots too, giving you maximum flexibility if you've just started planning your novel!

Need some eagle eyes on your work?

The best editors are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

The Fichtean Curve in action: A Confederacy of Dunces

This mid-century cult classic is a comedy of errors that follows the misadventures of Ignatius J Reilly, a foolish and delusional misanthrope who lives in 1960s New Orleans, unemployed and a benefactor of his hapless mother. Needless to say, spoilers ahead!

Part #1: Rising action

Stories employing the Fichtean Curve typically hit the ground running — the narrative starts in the middle of a crisis, and usually contains two or more crises in this period of ‘rising action’. Every crisis functions as a plot point where the character has some kind of learning experience; so this period is also where important character development, context, and backstory unfolds.

In a detective novel, these crises might consist of leads and dead-ends. In a romance, this could be a series of misfiring dates, followed by the travails of new-couplehood. In a fantasy novel, an apprentice wizard might be learning spells and getting into trouble time and again as his skills grow.

Q: What makes a compelling first chapter in a novel?

Suggested answer

The first chapter of any novel is so, so important. It's where the story is set up so that readers can get a taste of what they're in for over the next 8-12 hours. However, there is a multitude of elements that go into successful first chapters, and they must be expertly woven together to make it compelling. By the end of the first chapter, it comes down to one thing: if the reader isn't hooked, they likely won't continue. And they need three things to keep them interested.

- Curiosity

- Tension

- Emotion

The sooner these things become apparent in the pages, the better. Readers want to feel emotionally connected to the main character so that they can empathize with them, feel like they intimately know them, and root for them to reach their goal. They want to care about what happens to them. If there's tension, readers will worry about them and be curious about how it's going to play out. And when readers are curious, that means they're theorizing about what might happen. If they're theorizing, they're engaged in the story. Their brains feel like they're actively participating in figuring things out--and that's what makes them feel compelled to keep turning those pages.

My favourite novels aren't the ones that open with a beautiful sunrise or a description of the surroundings or backstory or having a character wake up. These are cliché in today's publishing landscape. Instead, they have opening lines or paragraphs that evoke such strong curiosity in me, something shocking or surprising or unexpected, that I'm hooked right from the start. These are the novels that hold my attention not just through the first chapter, but through all of them. The authors make sure there's curiosity, tension, and emotion present, along with other elements, such as a hint about the protagonist's internal conflict and flaws, an idea about goals and stakes, their desires, an imbalance of power, more showing than telling, etc. that contribute to my brain's need to feel engaged and interested.

So, it's not just about having all the elements that go into writing an exceptional novel. It's the art of weaving them all together in a style and voice that's intriguing and engaging from the very first page. Readers of fiction want to be entertained, so it's your job as the writer to make that promise and follow through with it by capturing their attention as soon as possible in the first chapter and not letting go until the very last page.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Starting with a strong opening line that is intriguing will help pull the reader into the narrative.

"Where is Papa going with that axe?" is the opening line of Charlotte's Web. We open with intrigue, and in the middle of the action of the story.

Then you want to have a strong build-up to the inciting incident, which should come at about 12,00-13,000 words into the story.

You want your main character to be likable and interesting to the reader.

You want to leave any backstory details for later on and keep the action of your opening scene continuous and going strong.

Then, if possible, you want to end this chapter with the promise of more "trouble" to come or an unanswered question regarding the trouble at hand, or at the very least, some ruffled feathers regarding your main character. There needs to be trouble brewing soon, and discomfort felt by your hero.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

CRISIS 1: Driving home after a heavy drinking session, Ignatius’s mother crashes her car. Confronted with a $1,000 fine (a small fortune at the time), Ignatius must get a job — the thing that sets our story off.

📚 The first job Ignatius lands is as an office clerk at Levy Pants. Disdainful of his new employers and believing the work is beneath him, he causes trouble writing fraudulent and insulting letters to clients, throwing away files, and starting a riot amongst the factory workers.

CRISIS 2: Ignatius’s ongoing belligerence and rudeness results in him being fired.

📚 Wandering through New Orleans, Ignatius happens upon Paradise Vendors, a hotdog stall. He is employed here, but once again causes mischief by eating copious amounts of stock and receiving a complaint from the health board.

CRISIS 3: Ignatius retains his job, but is punished by being made to work across town and debase himself by wearing a pirate costume.

📚 Here, Ignatius runs into Dorian Greene, a gay denizen of the French Quarter. After some discussion, Ignatius decides he wants to start a political party, for which Dorian agrees to host a launch event.

CRISIS 4: Ignatius turns up to Dorian’s event to discover that it is, in fact, a debauched party rather than a political rally.

Subplot

The protagonist's backstory and other crucial character development are interwoven into this period of rising action. Moments of high drama function doubly as action points and revelatory moments. Subplots/B character storylines can also run parallel to these crises.

📚 At University, Ignatius had a girlfriend called Myrna Minkoff. He still frequently exchanges letters with her in the hope of rekindling a romance. We learn about his younger days and discover that he’s always been somewhat of an outcast. Amidst the crises of the story, Ignatius often retreats to his bedroom and fills his diary. A prolific writer, he hopes (perhaps delusionally) to pen the next American masterpiece.

Part #2: Climax

The climax of the curve arrives towards the end and can be considered the dramatic peak of the story. The protagonist, after overcoming the previous crises, has been met with the ultimate impasse — a conflict that cannot be overcome as easily as previous roadblocks. Whether the character learns from their mistakes (or not) determines the outcome of the story.

Q: How can authors effectively build tension leading up to the climax?

Suggested answer

Well, the main method is to up the stakes as you go along. The more it matters emotionally to the characters and externally to their circumstances and the world around them, the more important that climax becomes. Every time you increase the stakes, the anticipation of readers goes up surrounding the climax and what might result. The final confrontation between hero(es) and villain becomes and edge-of-the-seat affair.

If you struggle with this, the technique I recommend is to examine the plot questions asked and answered. All plots are effectively a series of questions asked and answered. When you ask and how soon you answer is part of building tensions. Some questions carry over several scenes, some are answered right away. Some last whole chapters or several chapters. Some are asked at the beginning and not answered until the end, like the main driving core quest question of will good conquer evil? Will the protagonist get what he or she wants or needs? Will the villain prevail?

Make sure you are answering the questions you ask in appropriate places. Yes, you may want to set up a sequel and leave a few things hanging but the trick is to pick the right questions. The rest need to be answered, and figuring out which questions depend upon that climax and asking more and more of them as you lead up to it is a really great way to increase suspense and anticipation and lend that sense of urgency to the climax that keeps readers turning pages and dying to know what happens.

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Stakes need to be continually raised as the story builds to a climax. The problem[s] should be getting more and more difficult until the climax is reached.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Subtle foreshadowing is a solid way to build tension. Hinting at what's to come can prime the reader for the climax without revealing exactly what's coming—just that something is coming.

Well-written, lower-level conflicts between characters is another effective tool to build tension: short arguments, occasional emotional blow-ups, etc. These are, in effect, a kind of foreshadowing themselves, setting the reader up for the finale, whatever it may be.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

CLIMAX: Ignatius attempts to give a speech at the party but is booed offstage. This is the ultimate humiliation, at a moment when he believed that he was going to be celebrated.

📚 Faced with this crisis, he has a choice: a) deal with it, move on and grow, or b) relapse back into old behavior. Once again, Ignatius chooses the low road. Angry and deflated, he heads downtown to drown his sorrows at the bar. Here, a dog mistakes his pirate earring for a jumping hoop and attacks and badly injures him (talk about knocking a man whilst he’s down!).

Part #3: Falling action

This is where the story sees its resolution. Usually, unresolved plot strands are tied up, and the narrative arc of the protagonist is completed. The protagonist’s journey is likely to have been radically altered by this final, climactic event, and may also find their worldview radically changed as well. The falling action is likely to be where the moral arc of the story is made most evident.

📚 Ignatius is in the hospital recovering. Having almost reached the top of the proverbial mountain, he slips and hits every rock on the way back down and gets some retribution for his misadventures. Mr. Levy confronts Ignatius about his fraudulent letters in the wake of discovering a $500,000 lawsuit has been filed against him by a client — but another colleague takes the flack. He’s also punished by his mother for being a drain on her, as she calls a local psychiatric ward.

RESOLUTION: Suspicious that his mother has called for him to be taken away to a psychiatric hospital, Ignatius escapes to New York with Myrna Minkoff. Nominally he gets what he wants with Myrna, but because he hasn't changed — and he is still who he is — his unhappiness can be seen as a comeuppance of sorts.

Rather than bringing about a resolving radical change in thinking or beliefs, the climax in A Confederacy of Dunces simply gives Ignatius the impetus to escape New Orleans for good… having learned nothing.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

When should you use The Fichtean Curve?

As always, there is no 'best' or 'correct' structural method — just one that better suits a writer and the story they're telling. With that in mind, here are a few situations in which an author might want to use the Fichtean Curve.

When writing in a literary style

This approach is good for those writing literary fiction. Though it might sound counterintuitive, stories with less emphasis on plot can make use of ‘episodes’ as a way to develop their characters and create a satisfying story. For this reason, the Fichtean curve works well for those writing pieces of fiction that are less plot-driven. This is because a ‘crisis’ is a flexible structural format — it could be as small as a tense conversation, or as big as death, and can happen in the fictive past or present, becoming a self-contained episode.

Q: What advice or strategies can help authors experimenting with non-linear narratives create compelling stories?

Suggested answer

Experimentation is great, as are truly creative approaches to narrative! My only advice would be not to forget your reader – they will need some breadcrumbs or guideropes to help them follow you.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Read, read, read examples of books written this way, and see what you can glean from a best seller that uses this technique. Learn what you can and then apply it to your own work. Try out a chapter or two to see if this works before trying to complete an entire book.

Having a TOC - Table of Contents - in place before drafting the story will be crucial. You can be a "pantser" in this case, with no plan in place. You must plan ahead. A Table of Contents is an in-depth chapter-by-chapter outline of the book, complete with bullet points for every main event in each chapter. You want to have this completed and have this all make sense before drafting your book.

And finally, since this is a unique way to tell a story, you must ask yourself if this is the best way to tell this story. Be careful not to fall into the mindset of writing in a unique style just for the sake of being unique. The story must stand up well on its own and have a strong plot. If so, dive in. If not, see if a linear plot might work better.

You can always try a few chapters in different ways and see which one works the best.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For telling character-driven stories

Crises in rising action are designed to put a character through their paces. They present an opportunity for a character to make a decision and experience its consequences. To go back to our example, each new workplace Ignatius enters figures dually as a ‘crisis’ (or episode) and a 'test of personality'. Ignatius fails these tests at every level— even as the stakes become higher and higher. Readers are provided with a three-dimensional portrait of his malevolent and selfish nature precisely because these traits are teased out through his reactions to particular events.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

The narrative is driven by the resistance that occurs at each of these hurdles and has the added benefit of establishing a consistent pace and creating an element of suspense whilst also driving a plot forward.

So there we have it — everything you need to know about the Fichtean Curve! If you’ve been wooed by this story structure’s simple formula, why don’t you try and put it to practice with your own story?