Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 07, 2023

What is a Plot Point?

We’ve all read a book without a plot point, or, should I say, without a point to the plot. Every story needs a beginning, middle, and end — but it also needs plot points to guide the reader from one act to the next.

In this article, we’ll show why plot points matter, the difference between a plot point and plot, and two examples of popular books dissected by their plot points.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

What is a plot point?

A plot point is an incident that directly impacts what happens next in a story. In other words, it gives a point to the plot, forcing the story in a different direction, where otherwise it would’ve just meandered.

Any event in a story can be significant, but if it does not move the story forward, it is just a point in the plot — not a plot point. The latter must:

- Move the story in a different direction.

- Impact character development.

- Close a door behind a character, forcing them forward.

Think of it like a bolt, holding your story together: without it, you just have separate pieces of scrap metal. But connect them together and they form a whole, each piece informing the event before it and after it.

What’s the difference between a plot point and plot?

Plot points are big and exciting moments, and if you think back on a book you read a while ago, they’re likely the moments you’ll remember. Because of this, it’s easy to think of every event in a book as a plot point. But that’s not always true.

The plot is a chain of connected events that comprises the narrative. If one of those events does not have a concrete effect on the protagonist — and by extension, the trajectory of the plot — it is not a plot point.

An advisor might berate a prince for mourning the death of his father, but this isn't a plot point because it isn't necessarily pivotal — it doesn't convince Hamlet to keep a stiff upper lip for the rest of his life, after all.

But, when the prince sees his father’s ghost with his own eyes (and the ghost bids him to avenge its death), the prince has no choice but to act. There, you can see a plot point in motion, determining the story’s course moving forward.

Why is it important to identify plot points?

Mapping a story by its plot points illuminates why some books are page turners, while others never get turned past the first page.

First and foremost, plot points show you how a story works. Remember how plot points are like bolts? That’s not just because they hold the story together. It’s also because they’re tiny and significant. Once you link them together, you can understand how the whole story is built.

Stories are not complicated at heart.

The good ones are a series of:

This happened, so this happened, but then this happened, therefore this happened.

The bad ones are simply just:

This happened, and then this happened, and then this happened… with nothing connecting the events organically.

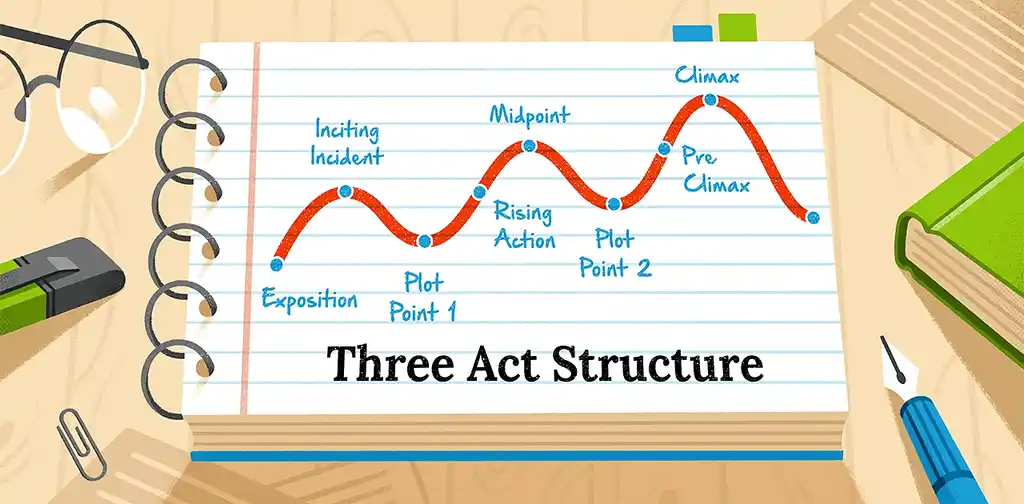

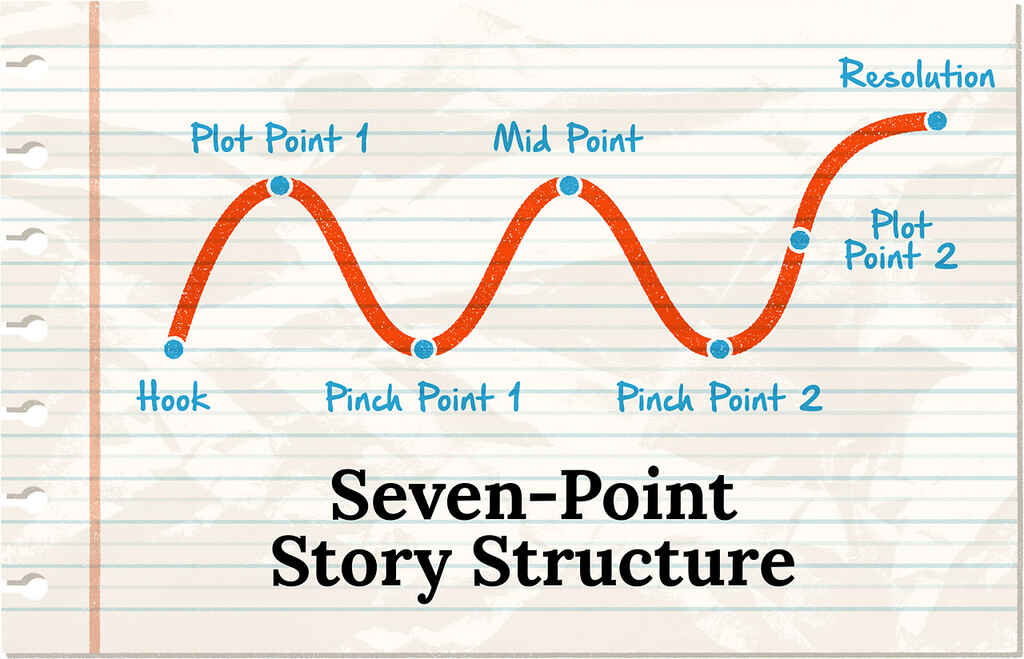

Understanding when plot points occur in a story will give insight into whether any particular story arc is being used. Some people argue that there only needs to be two plot points in a story, while others suggest much more, such as the Seven Point Story Structure we’ll use as a model here (and which we analyze in much closer detail in this post).

Let’s look at two vastly different but equally classic books — Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are — to see how well-structured stories often work with similar plot points.

The plot points of The Handmaid’s Tale

On the surface, the plot of Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel is thoroughly unique: a cocktail of historical precedence, futuristic speculation, unreliable narration, and a necessarily passive protagonist (as a woman living under a oppressive and sexist regime). All this might account for why it remains so popular to this day — in 2017, its TV adaptation swept the Emmys, and it was the most read book of that year according to Amazon.

However, dig a little deeper and you’ll find that its structure is comparable to other great stories.

Hook

A story must start off strong enough to keep the reader, you know, actually reading. Many refer to this feature as the Hook, or the Back Story — the point that pushes a novel into motion and automatically sets it apart from the millions of others out there.

A great story can do this off the strength of its premise alone. From the start of the novel, Atwood hooks us in by introducing readers to the primary conflict of Offred’s story: she is a woman in a world where women have no agency. We see how this conflict fits into her day-to-day life as Offred attends a Ceremony with her oppressor, The Commander. For her, this is a horrible but commonplace routine. But to the reader, it is new, and it hooks them with the desire to learn more.

A premise itself will never be enough to carry a novel. But it needs to be enough to hook the reader’s interest long enough to keep them on the line, until the first big reveal comes around and reels them in.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

First Plot Point

The Hook sets the stage for the first Big Event, also referred to as the Catalyst, the Inciting Incident, or, simply, the First Plot Point. This occurs somewhere around the ¼ to ⅓ mark in the story and signals the end of the beginning.

This First Plot Point should force the protagonist into the conflict. In The Handmaid’s Tale, it arises in the form of an invitation from The Commander to meet with Offred outside the Ceremony. In this world, such a meeting is expressly forbidden… and yet, so is acting against the wishes of a Commander. Thus, Offred is thrown free from the status quo, and the story changes course.

First Pinch Point

The middle of the story generally consists of the character reacting to the Big Event and its consequences. These are Pinch Points, and they put the character under pressure, forcing them to make a choice.

Characters will often spend this part of their story choosing to not act. Offred meets with The Commander. He coerces her into a sort-of affair, meeting with her regularly (albeit only to play Scrabble and read magazines) while hiding it from his Wife. Offred hesitates, but goes along with it. She has little choice in the matter but sees an opportunity to improve her situation if she can curry the Commander’s favor.

So, we see her reacting to the jarring call to adventure, but mostly with passivity. It will take a major turning point for her to react to it actively.

Midpoint

Perhaps the most crucial plot point occurs near the middle of a story. The Midpoint is a crucial turning point that forces the protagonist to stop reacting and start acting.

Throughout the story, Offred has looked back on the memories of her old friend Moira, a rebellious firebrand who provides her with hope that it’s still possible to exist in this world as an independent woman. However, when The Commander takes her to a brothel, Offred discovers Moira there, living freer than her modest counterparts, but still very much under the finger of the patriarchal regime. Offred realizes there is no hope for her to operate within the confines of this society and still retain some independence. Instead, she must take matters into her own hands.

Final Pinch Point

For the second half of the middle, the protagonist then experiments with agency, taking different approaches to overcome the central problem. This is another Pinch Point: our protagonist reacts to or acts on pressure and conflict, with middling success.

Offred tests her boundaries with small acts of rebellion such as refusing breakfast, toying with matches, and even entering an affair with Nick, one of the servants on the property. They offer her no hope of overthrowing the regime or even attaining personal freedom, but they still give the character an agency that did not exist before.

Final Plot Point

Going into the third act (or the beginning of the end, so to speak) there is often one Final Plot Point. This shows the protagonist at their lowest, having taken a profound misstep among their newfound actions which drives them directly into the Climax and Resolution.

In this example, The Commander’s wife discovers her husband’s affair with Offred. This presents Offred with an unpleasant choice — the terrifying uncertainty of seeking help in a world where she trusts no one, or the deadly certainty of suicide.

FREE RESOURCE

Three Act Structure Template

Craft a satisfying story arc with our free step-by-step template.

Resolution

A great story will end on a Climax, Realization, and Resolution, a series of events that bring the story and character arc in full circle. Usually, these revolve around a choice presented to the protagonist. No matter the decision they make, it will reveal something important — either they’ve changed, or they haven’t.

In Offred’s case, she chooses the former and tells Nick that she thinks she’s pregnant, reaching out and confiding in someone other than herself for the first time in the novel. This might not be the action-packed ending that comes to mind when you think of a Climax. However, it does exactly what it needs to do. It brings the conflict to a head and forces the character to make a crucial decision. At first, we saw Offred living in an oppressive, yet normalized certainty. By the end, she chooses agency over passivity, and uncertainty over certainty, no matter how dangerous it might be. This leads directly to the end, where Nick uses this information to break her out of The Commander’s house.

No more surprises exist here. The function of this point is simple: bring the story to a satisfying (if not necessarily happy) ending. The conclusion of a story doesn’t need to be sunshine and roses. But it needs to feel natural, like everything that came before led necessarily to one place.

Thus, the bare bones of The Handmaid’s Tale would look like such:

- Hook: Offred is forced into a Ceremony with The Commander in a world where women have no agency.

- First Plot Point: The Commander invites Offred to meet with him outside this ceremony, which is forbidden.

- First Pinch Point: She enters into an affair with The Commander hoping to leverage it into independence.

- Midpoint: They go together to a brothel where she finds even the most independent women are oppressed.

- Final Pinch Point: She enters into an affair with Nick as an act of agency.

- Final Plot Point: The Commander’s Wife discovers that they have been together, so Offred must choose between certain death (suicide) and uncertain danger (confiding in someone she isn’t sure if she can trust).

- Resolution: Offred makes her choice, telling Nick that she’s pregnant, so she is rescued.

Presented like so, it becomes apparent that each plot point feels like the natural extension of the last and moves seamlessly to the next. This creates the desired effect of any well structured story: an ending that feels both like a surprise and the only possible outcome when looking back.

The plot points of Where the Wild Things Are

Clocking in at barely 300 words, Sendak’s classic children’s book has a predictably simpler plot than The Handmaid’s Tale. And yet, broken down in the same way, it is surprisingly comparable. It has a beginning, middle, and end, with two Plot Points to transition between and one at the Midpoint altering the course of the story. It also has a narrative Hook, a handful of Pinch Points, and a Resolution.

Laid out by only its plot points, Where the Wild Things Are would look like such:

- Hook: Max is mischievous and dresses like a wild thing.

- First Plot Point: His mother yells at him and he yells back.

- First Pinch Point: She sends him to bed without dinner, so he sails to where the wild things are.

- Midpoint: They make him king of all wild things.

- Final Pinch Point: He sends them to bed without dinner, then realizes he’s lonely and wants to be loved.

- Final Plot Point: He journeys back home.

- Resolution: He finds his dinner waiting for him, still hot.

Where the Wild Things Are is a tightly structured story that moves naturally in a full circle and ends satisfactorily. More importantly, its bare bones bear uncanny resemblance to The Handmaid's Tale — and countless more stories in the Western canon.

Once again, these authors surely did not adhere to strict, structural guidelines in plotting these stories. All good stories simply flow in similar ways, ways that keep the attention of the person being told. In order to keep it flowing and not dribbling, keeping your plot points in mind is crucial.

2 responses

Lucas Cavalcanti says:

23/09/2019 – 06:49

Interesting article, I've enjoyed reading it. One correction though: Offred doesn't steal a match, she's given one - at least in the book. As a treat for accepting trying to get pregnant with Nick, Serena hands her a cigarette and says she can ask Rita for one match. The way she tests her boundaries with it is by thinking of using the match to set the house on fire. Anyway, once more: excellent article. Greetings from Brazil :)

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

09/10/2019 – 12:16

Thanks for the correct, Lucas. We've made the change. Keep up the eagle-eyed reading!