Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Situational Irony: 11 Examples That Will Make you Think

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Situational irony takes place when, in a twist of events, the actual outcome of a situation significantly differs from a person or character’s expectations about it. Real-life examples of situational irony include a fire station burning down, a traffic cop getting a parking ticket, and a dentist eating too many sweets.

Situational irony differs from dramatic irony in that the reader or audience doesn’t usually know about the plot twist ahead of the characters. Instead, the unexpected outcome surprises both the characters and the audience. For example, if a detective appointed to solve a crime is later found guilty of committing it, that’s situational irony. If readers already know it’s the murderer that has been hired as a detective, that’s dramatic irony. (For more examples of dramatic irony, head to this post.)

To identify situational irony in a text, look for a contrast between what is anticipated and what actually happens. If you’re surprised things ended up how they did, the author might well be using situational irony.

Writers typically use situational irony to reveal character flaws or strengths and highlight themes of unpredictability, fate, and the contrast between appearances and reality.

To better understand how this literary tool impacts readers, let’s analyze some situational irony examples from literature and film.

FREE RESOURCE

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry

In the short story "The Gift of the Magi" by O. Henry, married couple James and Della cannot afford to buy each other special gifts for Christmas, but they independently decide to go out of their way and surprise each other anyway. Della decides to sell her hair (which her husband adores) to buy him a watch chain. At the same time, James chooses to sell his watch to buy her a set of ornamental hair combs.

Q: What daily writing routines can help authors maintain consistent productivity?

Suggested answer

+ Never underestimate the power of enough sleep. This can cure more things than we know - how we show up, what we're capable of tackling each day.

+ Nourishing food to fuel the mind.

+ Movement - even if it's a walk around the block listening to a podcast, music or just deep in thought (often the best times when ideas arise).

After these three things are locked in:

+ Quiet, undistracted time blocks (even if it means phone in another room for 90 mins)

+ A laptop that has nothing else except Word on it (no website access).

+ For those who are visual, keeping a yellow sticky note daily "checklist" on a wall, to encourage a daily writing tally.

+ Ask for feedback for continual improvement.

Leoni is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There are four things that I consider before settling in to write.

What sounds are there? The best is silence, but in a city environment this is impossible. If there are specific loud that I want to block out, I listen to drone music. This consists mostly of long, sustained notes (no melodies) and comes from the American and German post-war experimental musical traditions. The texture of the sounds is often rich which works for this purpose quite well. It has a meditative effect. Failing this, music without lyrics is also good.

What is my phone doing? Just switch it off.

Social media. Along with my phone, this is designed to distract. What I do is log out of my social media accounts. If I automatically go back in, I'm then met by the login page. This doesn't sound like much of a difference, but is just enough to nudge myself into becoming mindful of what I'm doing and what my present purpose it. And mindfulness is key.

Lastly, I take a page of Hemingway's advice: "The first draft of anything is s**t." It's ok to produce bad writing. In fact, it's totally ok; actually it's great. Why? Because my ideas are now down on the page, even if it's absolutely horrible. Nobody ever simply writes a finished product straight off the bat. I'll make it better later and that is a different process.

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Get all domestic and admin chores out the way first, so that there is nothing else on your mind when you sit down to write. Then just stick at it for as long as possible.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In this classic example, what’s ironic is that both characters sacrifice something meaningful to surprise their partners and make them happy, but end up disappointed after losing something valuable and receiving an unwanted gift. This double irony results in a sad effect that brings the reader closer to both characters, as their dedication to each other overshadows their unfortunate gift exchange.

Antigone by Euripides

Antigone, Euripides's sequel-of-sorts to Oedipus Rex, takes place in Ancient Thebes, where Antigone’s brothers Eteocles and Polynices both died, fighting each other in battle. Antigone’s mission is to bury Polynices, whom the new king Creon refuses to bury because he sees him as a traitor for joining a foreign army.

Antigone can distinguish between city law and the expectations of the gods, and knowing that Polynices must receive funeral rites to enter the Underworld, decides to bury him anyway. Creon discovers her plan and has her arrested and sentenced to death. His son, who is betrothed to Antigone, begs his father to spare her soul 一 but he ignores him and laughs it off.

Tiresias, a blind seer, warns Creon about the dreadful consequences of his disrespect for the dead, saying the Gods are angry. Worried, Creon decides to reverse his decisions 一 but it’s too late. A cascade of death curses him with pain: Antigone is found dead, which leads Haemon to kill himself, which brings his mother Eurydice (Creon’s wife) to commit suicide, too.

The irony of the situation is that Creon’s arrogance and disrespect for the dead led his closest family members to tragically die. Even more ironic is the fact that the blind seer is actually the character with a clairvoyant understanding of events, seeing things exactly as they are despite his physical blindness. In a devout society, this situational irony served as a powerful reminder to obey and honor the gods, or pay the cost.

🖊️

Which famous author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

Othello by William Shakespeare

In Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Othello, the jealous Iago tricks Othello into believing that his wife Desdemona has been unfaithful to him (giving rise to a lot of dramatic irony, as the audience is aware of Iago’s deceit long before Othello).

One example of situational irony occurs when Othello kills first Desdemona, then himself, in their marriage bed between the wedding sheets. Something that ought to be associated with love and new life is ironically turned into an object of death. This powerful reversal heightens the emotional impact of the play and highlights how completely Iago’s manipulation has destroyed the newlyweds’ relationship.

The Necklace by Guy de Maupassant

Set in 1884 Paris, 'The Necklace' by Guy de Maupassant tells the story of Matilda, a middle-class woman who desires jewels and fine clothing. When her husband comes home with an invitation to a ball at the Palace of Ministry, she turns it down 一 complaining she has nothing to wear. He sacrifices his savings to buy her an appropriate outfit, but she’s then faced with her lack of jewelry, so she borrows a diamond necklace from a wealthier friend.

Q: What tools or apps actually make a difference in streamlining the writing process?

Suggested answer

Today we have a plethora of excellent software programs for writing, such as Reedsy Studio, Scrivener, and Grammarly. Some writers use ChatGPT, although I would not recommend using an AI generative language model to help writing. This is because it bypasses the process altogether, replacing the writer. What would be the point of that?

Even the oldest and best-known program, Microsoft Word is still excellent. But there is one older – far older – trick to helping the writing process. This is articulating your writing ideas out load. I'm sorry if it sounds mundane and less flashy!

It is surprising how difficult this can be sometimes. Often, a writer will have an idea or set of ideas but having never explained them aloud, might struggle with clarity at the detailed level. When reading over their work, they are reminded of the ideas; the writer is not merely reading here, they are remembering things that are not on the page!

So, trying to explain it to someone who does not know these ideas is crucial. This is why critique groups are an excellent way of improving one's writing. Often – after a deep explanation and perhaps some questions back and forth – I have heard the friend or other writer say, "ok, well write what you've just said!"

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

At the ball, Matilda enjoys the life she always dreamed of, but also loses the necklace. To return it, she and her husband buy another one using their inheritance money and taking up a loan. They then start working two jobs to repay the debt, considerably lowering their living standards. Many years later, they discover that the original necklace was fake and worthless.

It’s hard to miss the situational irony in this classic short story. Instead of helping her climb the social ladder, Matilda’s unhealthy obsession with wealth and status leads her and her husband to absolute misery. Both funny in its reversal of the readers’ expectations and serious in warning against greed, the story uses irony to ask readers if the things they want really matter.

The Tortoise and the Hare by Aesop

In Aesop’s fable The Tortoise and the Hare, even young readers know that the hare should be able to beat the tortoise in a race. When the tortoise ends up victorious because the hare thinks he has time for a nap, the situational irony teaches children an important lesson about the dangers of arrogance. The tortoise inspires us with his steady perseverance and reinforces the message that hard work beats talent when talent can’t be bothered to work hard.

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata tells the story of Keiko Furukura, an introvert and outsider who seemingly finds her calling when she lands a job at a convenience store. In the regimented environment of a konbini, guided by manuals and clear rules, she learns exactly what to do to be liked and respected 一 and what it means to have a sense of purpose. Many years later, having been pressured by family and colleagues to improve her position in life, she quits her job and gets married — but soon enough realizes that her true place is at the convenience store where she returns to work.

Keiko’s situation is highly ironic: she only feels empowered, fulfilled, and liberated as a convenience store employee, an alienating job that demands she set any sense of personality aside. Instead, she finds society’s pressures to pursue individuality repressing, in the same way that most people find jobs like hers strip them of their freedom. By turning society’s standards on their head, Murata uses situational irony to create an unexpected, funny, and thought-provoking effect, really getting readers to reconsider their definition of ‘normal’.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The book Erasure by Percival Everett tells the story of Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, an educated man who wants to write fiction. Still, no publisher supports him because, as a Black author, they expect him to write about the hardships of Black people.

Q: What are the most common mistakes writers make when breaking up paragraphs, and how can they improve readability?

Suggested answer

In fiction, the most common--and confusing!--issue I see with paragraph breaks occurs in conversations between characters. Authors almost always follow the rule of starting a new paragraph with each change in speaker, but sometimes, action beats (phrases describing what a character thinks or does) don't follow the same guidelines. This affects clarity: readers can lose track of who says what when character A's dialogue and character B's actions appear in the same paragraph. Check out this example:

"I'm not convinced," Barker said.

"But the DNA doesn't lie. And the soil traces exactly match the vic's compost."

Clark shifted in his chair, leaning to snag the soil analysis from Barker's desk. "Can't argue with that," he said, "but there's still the Ring footage."

That last sentence was actually spoken by Barker, not Clark, but the placement of the action beats muddies the exchange. One simple paragraphing adjustment fixes the issue, with no rewriting needed:

"I'm not convinced," Barker said.

"But the DNA doesn't lie. And the soil traces exactly match the vic's compost." Clark shifted in his chair, leaning to snag the soil analysis from Barker's desk.

"Can't argue with that," he said, "but there's still the Ring footage."

Stephanie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The biggest mistake an author can make when breaking up paragraphs is failing to maintain clarity and flow. Paragraphs are essential for structuring writing (whether this be fiction or non-fiction!), and poor paragraphing can confuse or disengage readers. Key errors include overcrowding paragraphs with multiple ideas, resulting in overly long, run-on paragraphs which overwhelm readers or breaking paragraphs too frequently, resulting in a choppy, disjointed narrative (where not used for effect).

A typical rule of thumb suggests a well-crafted paragraph should convey one central idea, action or theme. Authors should begin a new paragraph whenever introducing a new topic, thought or perspective. In fiction, this includes changes in setting, time or action and each time a new character speaks during dialogue. For non-fiction, paragraphs should align with shifts in argument or explanation.

Varied paragraph lengths can enhance rhythm and readability. Short paragraphs are impactful and ideal for highlighting key moments or emotions. Longer paragraphs, however, can delve into detail or explore complex ideas. Not varying length can disrupt your balance and writing’s overall engagement.

It’s also important to consider overall readability. Large blocks of text are visually intimidating and harder to process. Modern writing often benefits from concise, three-to-five-sentence paragraphs (although deviations for stylistic purposes are acceptable). On the other hand, breaking a paragraph prematurely—especially without completing an idea—can confuse readers and diminish the narrative’s flow. Similar to this, the transitions between your paragraphs also matter. Smooth shifts can be achieved through linking phrases, repeated keywords or logical progression of ideas, effortlessly guiding readers through the story.

As indicated above, a common error I’ve noticed in clients’ work comes in their writing dialogue. Failing to start a new paragraph for each speaker creates confusion and uncertainty. Consistently breaking paragraphs for dialogue improves clarity, helping readers follow the conversation and imagine the scene in real time, creating enhanced drama, tension or even humour.

Ultimately, paragraphing is both a technical and stylistic skill. Experienced writers often break conventions intentionally to suit their voice or genre and this can be done well. However, understanding the key principles to paragraphing ensures these choices enhance rather than hinder the narrative.

The biggest takeaway is to prioritise the reader’s experience. Paragraphs should guide them through your writing, enhancing clarity, rhythm and emotional impact. Avoid errors like paragraph overload, excessively long blocks or unclear transitions, which can detract from your message. Remember: good paragraphing is the first step to ensuring reader engagement.

Cameron-rose is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In my experience (and this mainly applies to nonfiction writing), it's usually a matter of not seeing a paragraph as a coherent unit with an introduction, development, and conclusion. The start of a paragraph should function as a mini thesis statement for what's going to be discussed. The meat of the paragraph would elaborate on that first sentence or two. And the final sentence or two should wrap up the main idea and help transition to the next paragraph. You can't go wrong with this simple structure.

For fiction, of course, things aren't set out so strictly, because we also need to keep the flow and artistry of the text in mind. But when in doubt, a good rule of thumb is to make sure a paragraph conveys a single, complete emotion or action and helps the reader move on to whatever is going to happen next.

Marisa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The most common mistake when making paragraph breaks is to follow a standard length. Remember that the look of the page should not be considered when deciding this. This mistake is based on a wrong understanding of what a paragraph is. So, this begs the question: what is a paragraph?

Put in simple terms, a paragraph is a unit of thought. It is the presentation of a single idea. Don't be afraid of writing paragraphs and varying lengths if it's needed—it will make your content clearer.

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A lot of writers will sometimes put in too many paragraph breaks which, in some cases, breaks up a character's dialogue from their actions, which can cause confusion regarding who's speaking in any given scene. Keeping a character's dialogue and at least some of their actions goes a long way to reducing that confusion. However, other writers don't include enough paragraph breaks, and you wind up with a hard-to-read block of text that requires being read and re-read several times to parse what's happening, who's saying what, etc. Another quick bit of advice I'd give on this topic would be to start a new paragraph when you're switching subjects—even fairly slight switches in subject and tone can warrant a new paragraph, and this gives the reader a feeling of hitting a sort of mental refresh button as they're reading, which subconsciously spurs them on. As with all things, this needs to be approached with balance in mind, but finding that balance will make your text more easily readable.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

By far the most common issue I see regarding paragraph breaks has to do with breaking scenes involving dialogue and action. Some writers don't break paragraphs when a speaker changes, which is a Writing 101-level error, but what I generally see is more insidious: associating one character's actions with another speaker's dialogue. For example:

"I don't know what to think," Joe said. Mary stood up.

"I know what I think. I'm leaving."

vs. the correct:

"I don't know what to think," Joe said.

Mary stood up. "I know what I think. I'm leaving."

There seems to be an assumption that "break when a new character speaks" means that a paragraph containing dialogue must begin with the dialogue. This often goes hand-in-hand with overuse of dialogue tags (he said, they whispered, etc.). A simple way to elevate the quality of any fiction writing is to use action beats, not dialogue tags, to indicate who is speaking -- which means associating the character's actions with their words as in the second example above.

Elizabeth is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Enraged, Monk decides to write a parody novel narrating the “life in the ghetto” of a troubled Black young man, to expose racial stereotyping in publishing. Ironically, the novel gets picked by a major publisher and becomes a success. Monk finds himself on a book tour promoting a story that perpetuates the stereotypes (and supports the industry) he’s fighting against.

Everett makes the reader empathize with Monk’s frustration, then uses irony to highlight how difficult it is to change the entrenching system we live in 一 even with good intentions. More importantly, the comic nature of the book contrasts with the serious issue at hand, posing the question of whether a text can be valued for its content regardless of an author's race.

The Incredibles

In Pixar’s animated movie The Incredibles, Mr. Incredible stops a man from killing himself. Yet in an example of situational irony, he is not praised for saving the man’s life, but sued — and eventually forced to stop using his superpowers and go into hiding.

This irony reinforces the film’s satirical critique of modern society, which it portrays as overly litigious and ungrateful towards acts of heroism.

Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Poetry can also contain irony. Ozymandias tells the tale of a stone statue commissioned by a King. On the pedestal are the words:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The King expected the statue to immortalize his greatness. But the real outcome is not as grand: his face is shattered, and the decaying ruins of the monument lie in a desert where very few people ever come across them.

Shelley uses situational irony to remind us of our own transience in the grand scheme of things. He invites us to reflect on the fleeting nature of power and earthly achievements.

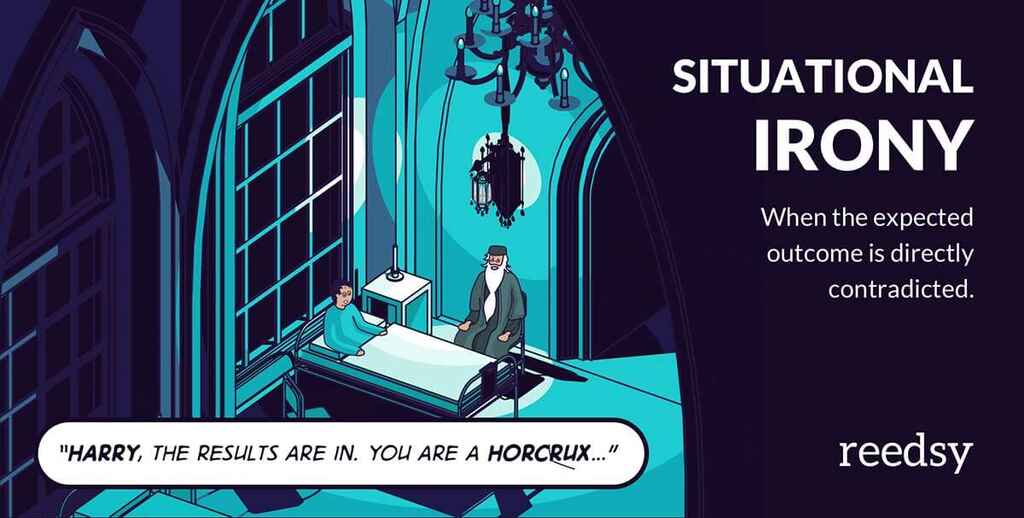

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling

Throughout the seventh book of the Harry Potter series, readers follow Harry on his quest to find and destroy Voldemort’s six Horcruxes. At the novel's end, we discover that there is a seventh Horcrux, so to speak, and it's Harry himself.

This unexpected twist also comes with the ironic realization that Harry must sacrifice himself for Voldemort to die. So he willingly goes to meet Voldemort — and his own death. But when Voldemort uses the killing curse on Harry, it has the opposite of his desired effect. Harry lives while the Horcrux dies, bringing Voldemort closer to his greatest fear: mortality.

In this way, Harry being a Horcrux is a double case of situational irony. Harry believes he must die to vanquish his enemy, whereas Voldemort thinks he is killing Harry, but he’s actually killing himself. With an unexpected turn of events, Rowling solves a high-stakes conflict, built up across several books, giving the readers the payoff (and sense of relief) they were looking for.

A Lamb to the Slaughter by Roald Dahl

In this typically twisty short story from Roald Dahl, a betrayed housewife kills her husband with a frozen leg of lamb. When the cops arrive at her place to solve the crime, she cooks the lamb and feeds it to them, effectively making them dispose of the evidence.

It’s a double case of situational irony: when you expect the housewife to be heartbroken about her husband's desire to separate, she abruptly kills him. When you expect her to break down and confess her crime, she calls the Police and blatantly serves them the incriminated weapon.

By carefully executing twists and turns, the author emotionally engages the reader, provoking a mixed reaction of disbelief and excitement. Since situationally ironic storylines inherently possess an element of surprise, they're common in the thriller, crime, and mystery genres.

Overall, you can use situational irony in different ways: to deliver your story’s message in unexpected ways, lightheartedly invite readers to reflect on serious matters, or entertain them as they observe a character's expectations clash with reality.

Next up, we'll be looking at dramatic irony examples 一 which will complete your knowledge of the types of ironies!