Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Falling Action: Definition, Tips, and Examples

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

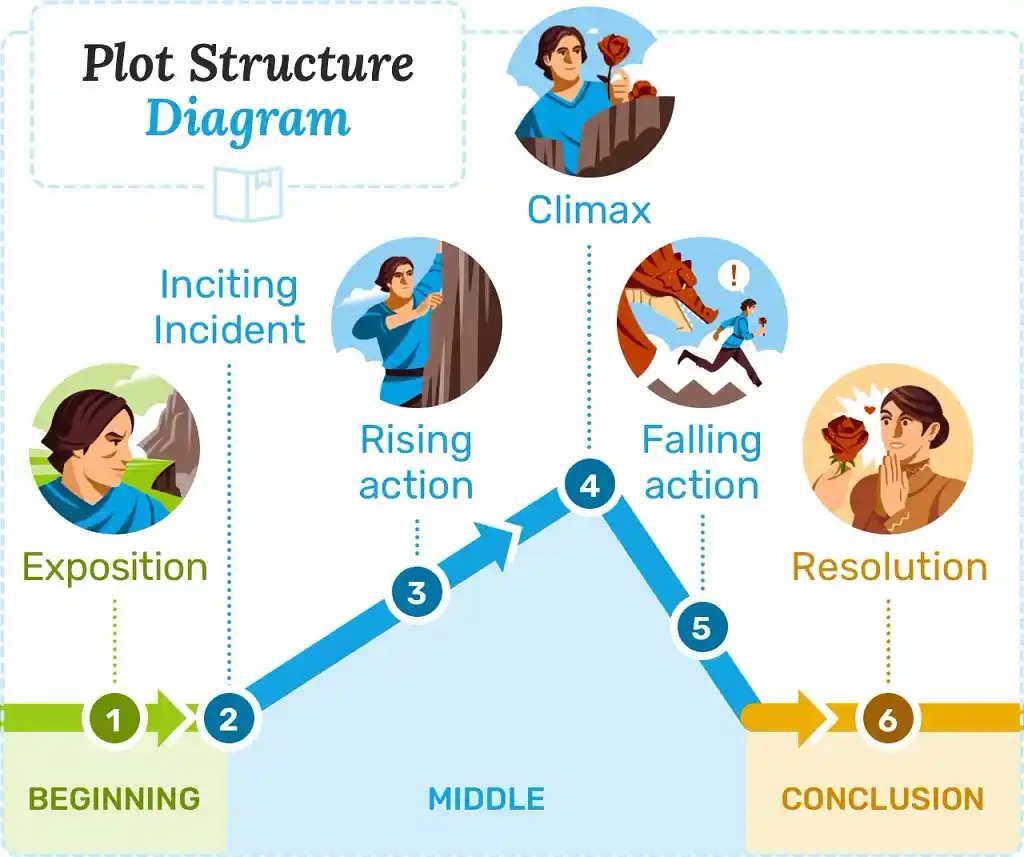

View profile →You may have heard the saying, “What goes up must come down”. This universal truth applies not only to life, but storytelling as well. Just as a story’s tension climbs throughout the rising action, it comes back down during the falling action. Falling action bridges the climax and the story’s ending, allowing the narrative to reach a satisfying conclusion.

In this post, we’ll cover what falling action is, explore its role in storytelling with examples from literature, and share some top tips to help you utilize it effectively in your writing.

FREE RESOURCE

Three Act Structure Template

Craft a satisfying story arc with our free step-by-step template.

What is falling action?

In a narrative, falling action refers to the sequence of events that take place between a story’s climax and resolution (or dénouement). This is the plot element where the dramatic tension from the climax begins to ease, and the focus shifts to its aftermath. During this phase, characters will often begin to process the events of the story, while loose ends are gradually tied up, paving the way for the final resolution.

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, the falling action follows our heroes on their journey home following the destruction of the One Ring. In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, the falling action unfolds as Utterson uncovers Dr. Jekyll's confession, revealing the truth behind the story's central mystery.

Falling action de-escalates the tension

Tension is at an all-time high during the climax, and the falling action serves as a much-needed de-escalation; it gives readers space to process the events of the climax and find some closure. Without this key element, a story’s ending may feel abrupt or incomplete.

Although the tension should remain on an overall downwards trajectory, new conflicts can be introduced during this phase. Characters may face minor obstacles on their way back home, or get into arguments about the events of the climax.

To evoke a stronger emotional reaction, some authors deliberately end the story at the climax. Think of Shirley Jackson’s short story The Lottery; the tale ends (spoiler alert!) as soon as the “winner” is stoned to death by all the other villagers. The lack of falling action robs the readers of their time to process this sudden revelation, and the story is all the more horrifying because of it.

It shows the all-important aftermath

Most stories, however, include at least a short passage showcasing the impact of the climax on its characters. The long-term changes to everyday life are typically reserved for the dénouement, which provides a glimpse into the future once things have settled down. However, it’s not realistic for everything to go right back to normal immediately following the climax.

In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J. K. Rowling, the story doesn’t skip from Harry defeating Voldemort straight to the cozy conclusion. Instead, we see the immediate aftermath of the climax: Kingsley Shacklebolt is named temporary Minister for Magic, the innocent are released from the wizard prison Azkaban, and Harry talks to Dumbledore’s portrait about his choice not to keep the all-powerful Elder Wand.

Harry makes the important decision not to keep the elder wand. Image: Warner Bros.

It ties up loose ends

The falling action also addresses any unanswered questions the reader may have. It is rare for every conflict to get resolved in the climax; chances are there are some seemingly insignificant or puzzling events left lingering from the rising action that can only now be explained. For example, in the falling action of The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes reveals (spoiler alert) Stapleton’s clever use of phosphorus to trick people into thinking that his ordinary hound was supernatural.

Of course, falling action doesn’t have to answer all the readers’ questions — particularly if a sequel is on the cards! In fact, the falling action is a good place to introduce an enticing cliffhanger or hook to set up the next book in the series.

It adds thematic depth

Finally, falling action can be used to explore themes further. This is the phase where you can drive home your story’s core message by exemplifying it in your characters. For example, George Orwell’s message that absolute power corrupts absolutely is highlighted in the falling action of Animal Farm as the pigs gradually begin to resemble the human oppressors they initially fought to overthrow.

If you want to explicitly spell out your core message, that’s better saved for the dénouement, as in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, which ends with the line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Let’s look at some examples of falling action in well-known stories, both old and new. (Warning: major spoiler alert!)

4 examples of falling action

Hansel and Gretel by the Brothers Grimm

Hansel and Gretel is a fairytale about two children whose parents are too poor to feed a family of four and so decide to abandon them in a forest. As they wander around the forest, the children stumble upon a house made out of sweets. Unfortunately for our poor protagonists, the house belongs to a wicked witch, who is dead set on fattening up Hansel to eat him and putting Gretel to work as her servant.

The climax occurs when Gretel pushes the witch into the oven, killing her. While the story may have reached its climax at this point, it has yet to reach its conclusion — the children must still find their way home, and readers will be curious to know whether or not Hansel and Gretel’s parents will welcome them back with open arms. All of this occurs as part of the falling action, while the happily-ever-after takes place in the dénouement.

The Wizard of Oz by Frank Baum

In The Wizard of Oz by Frank Baum, a tornado drops Dorothy in the magical land of Oz. In order to return home, Dorothy must travel to the Emerald City to ask a Wizard how she can get back to Kansas. She makes three friends on her quest, each with their own desires: the Scarecrow, who wants a brain; the Tin Man, who wants a heart; and the Cowardly Lion, who wants courage. The Wizard tells them he will grant each of their wishes, provided they kill the Wicked Witch of the West.

After Dorothy melts the Wicked Witch of the West in the climax, the falling action sees the friends return to the Emerald City, only to discover that the Wizard is an imposter with no real magic powers. Nevertheless, he teaches Dorothy’s companions that what they were seeking was inside them all along, and the Good Witch tells Dorothy how to get home.

The falling action de-escalates the remaining tension and moves the story towards a happy ending, despite a few minor obstacles, such as Dorothy missing her ride home in the hot air balloon thanks to her dog Toto. Although this is a new conflict that has to be resolved, it’s fairly minor compared to the dramatic final face-off with the Wicked Witch of the West, and therefore still a part of the falling action.

The falling action also explores the book’s core theme of self-belief; even though the Wizard is an imposter, he is still able to show the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion that they are capable of intelligence, love, and bravery — they need only believe in themselves.

The Fault In Our Stars by John Green

The falling action in John Green’s The Fault In Our Stars is far less uplifting, yet heartbreakingly powerful. The story follows two teenagers, Hazel and Augustus, who meet at a cancer support group. Augustus is in remission, while Hazel’s cancer continues to spread — throughout the story, both the characters and the audience are led to believe that Hazel will succumb to her fate in the climax. In a tragic twist, Augustus is the one that passes away, leaving Hazel alone with his memory.

In the falling action, Hazel (and the reader) must mourn her lost love and learn to come to terms with her grief. Hazel comes to understand that, even if death is inevitable, it’s our relationships with others that makes life meaningful.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins is set in a dystopian future in which child tributes are made to fight to the death in a huge arena as punishment for their ancestors’ rebellion against The Capitol.

In the climax, protagonists Katniss and Peeta decide they would rather die together than survive alone, and are about to eat poisonous berries and spite the Capitol by depriving them of an ultimate victor. The falling action begins with the hasty announcement that there can be two winners after all, before the protagonists are checked into a hospital, and a series of interviews take place following their victory.

However, the falling action leaves plenty of questions unanswered: will Katniss face any punishment for her act of rebellion? Will she end up with her “star-crossed lover”, Peeta, or her childhood friend, Gale? These lingering uncertainties help keep readers engaged, and generate interest in the next book in the trilogy.

Now that we’ve explored some examples of falling action in storytelling, let’s go over some tried-and-tested tips to help you write compelling falling action in your own writing.

3 tips to write falling action

1. Tie up your loose ends

One of the most frustrating things a reader can experience is reaching the end of a book — or worse, a series — and still having unanswered questions. To avoid any potential headaches, re-read your rising action and climax, noting down any lingering plot threads that need to be addressed. That way, the only remaining loose ends will be deliberate cliffhangers.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

2. Keep the action falling

Falling action should fall steadily like a leaf drifting from a tree, not erratically like a rollercoaster. With that in mind, return to your list of unanswered questions that need to be resolved, add any new conflicts you want to introduce, then arrange the items in descending order of tension. Aim to structure your falling action so that it begins with the most tense item, and ends with the least.

Of course, writing is by no means an exact science; readability remains the number one priority, so feel free to shuffle your structure around accordingly.

3. Keep it short

In stories following Freytag’s pyramid, the falling action is about equal in length to the rising action. However, these stories tend to be the exception rather than the rule; most of the time, the climax occurs well over halfway through the story, and the falling action tends to be much shorter than the rising action.

How long should the falling action be exactly? There’s no hard-and-fast rule — take as long as you need to show the aftermath of the climax and tie up any loose ends. Don’t stress about making your falling action longer than it needs to be. Sometimes, it only takes one or two chapters, and that’s fine!

In the spirit of keeping it short, we’ll end our post here. There’s plenty more to read though! Don’t miss the last post in our guide on the final scene of a story: the dénouement.