Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Jan 06, 2025

The 6 Key Elements of Plot, Explained (+ Plot Diagram)

Nick Bailey

Nick is a writer for Reedsy who covers all things related to writing and self-publishing. An avid fan of great storytelling, he specializes in story structure, genre tropes, and character work, and particularly enjoys sharing insights that spark creativity in fellow writers.

View profile →Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →Every story is unique — or at least it should aspire to be. But if you look beneath the surface of storytelling, you’ll find a few recurring elements that come together to create a satisfying plot. From the exposition to rising action to the story climax, these elements of plot help provide context, stakes, and tension in order to keep readers invested from beginning to end.

In this post, we’ll walk you through each plot element and provide examples of how authors have implemented them in popular works of fiction. We’ll also show you how to plot your own story in our free writing app.

The 6 key elements of plot:

What is plot?

Plot is the series of events that comprise your novel’s narrative. Crucially, a plot is not just what happens in a story — it’s how and why those things happen. And a story is more than a simple recounting of events; every scene should be carefully arranged to create meaning, build tension, and develop characterization. Each one should build on the events of the last, and set up the one that follows.

A great plot combines various key elements. From the inciting incident to the satisfying resolution, each element should connect to form a cohesive journey. Many writers find inspiration in common story structures, like the three-act structure or the Hero’s Journey, to help shape their narratives. For a more detailed overview on plot, check out our guide!

Q: What is the difference between “story” and “plot” in narrative craft?

Suggested answer

Story is a description of a connected series of events, with a clear beginning, middle and ending, while plot is the organization of those events – how we get from beginning to middle to end. So, for example, you might have a plot where events are ordered chronologically or where you move back and forth in time, or there could even be different threads within your manuscript.

To create an exciting and enthralling story, where readers will feel compelled to turn the page to find out what happens next, think about change and conflict. These should drive events and motivate your characters until the story reaches a satisfying conclusion. What conflicts or challenges do your characters face as the story progresses? How do these characters develop?

To create a successful plot, carefully think about organizing the events in a way that feels effective and purposeful. What are the best places to start and finish? Are there enough 'hooks' to keep readers engaged? Is the tension building up before a final resolution? Sitting down and plotting out before putting pen to paper (or opening up that blank document!) can really help you ensure that you are hitting that beginning, middle and ending in a satisfying way that will sustain your readers' curiosity and engagement with your writing.

Jenna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Plot is what actually happens in the book. The sequence of events that takes place. While the story is more about the reasons behind what happens. Why does your main character want what she wants? What is she feeling and thinking at any given point? What do characters feel about each other and why? Story dives a bit deeper into the heart of the book, and not just the events that transpire. Strong books have both a strong plot and a strong story to them.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

To get a better idea of how a plot is structured, let’s take a look at a plot diagram.

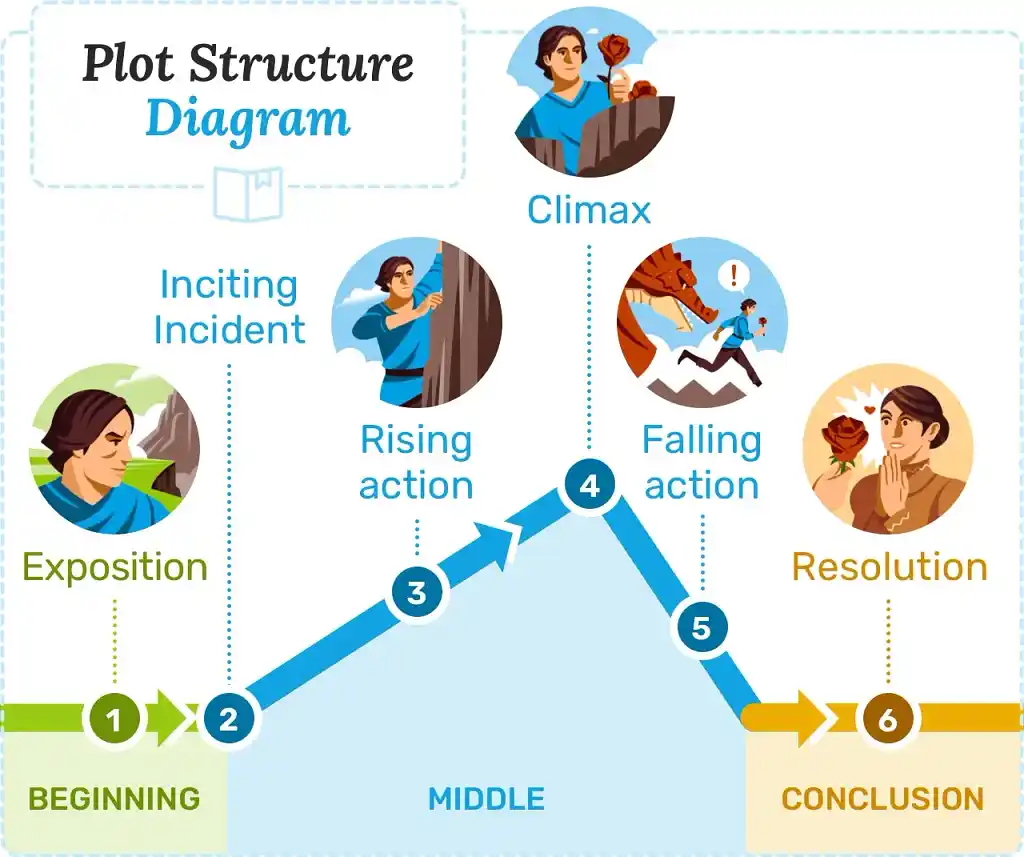

What is a plot diagram?

A plot diagram is a tool you can use to map out tension throughout your story. Having a visual aid to organize your major story beats can help you understand each section more clearly.

Think of a plot diagram like a mountain. Exposition sets the stage at the mountain’s base, then the inciting incident launches the story upwards. Tension builds along the mountain's upward slope in the rising action phase — until the thrilling climax at the summit. After the story’s dramatic high point at the peak, the descent begins and the action falls, before all those loose ends are wrapped up at the foot of the mountain in the dénouement.

The beauty of a plot diagram lies in its flexibility. The order of events will generally remain the same, but the shape of your “mountain” can vary widely depending on your narrative. A story following our plot diagram will have a straightforward flow as the tension steadily rises towards the climax, followed by a prompt resolution. Conversely, a thriller novel with a sudden spike in tension might have a much faster ascent in the rising action phase, and stories finishing on a cliffhanger may not descend at all!

Regardless of your preferred structure, mapping it out on a plot diagram will help you visualize how your story flows from one beat to the next. Now let’s take a closer look at the diagram’s different phases to get a better understanding of how each one functions within your story.

The 6 classic elements of plot

Each of the six core elements of plot builds off the others to create a compelling story — so recognizing how they connect to one another will deepen your understanding of storytelling, and help you engage readers on a more fundamental level.

Let’s start with the foundational level: exposition.

Exposition

Every story will have some degree of background information that needs to be explained; that’s where exposition comes in. Exposition can be as simple as introducing a character or describing the setting, to delving into more complex elements like the rules of your world or the underlying societal or political structures that will drive the conflict.

Q: What are effective techniques for incorporating exposition into a story without disrupting the flow or pacing?

Suggested answer

I see poorly integrated facts in nonfiction all the time. You'll be reading beautiful prose and all of a sudden you're hit with what reads like a copy-and-pasted section of Wikipedia. Writers need to take the facts and make them their own. That means finding ways to make them vivid and immediate to the reader and weaves them into the narrative.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The best way to get exposition in is through dialogue. The caveat, of course, is to be careful that it comes across naturally. For instance, if your characters are telling each other things they would know, the reader will know you're only doing that to get the information to the reader, which will greatly reduce their suspension of disbelief.

The second best way, in my opinion, is through thoughts. Again, though, the character needs to think things they would actually think in their situation. For instance, in a fantasy novel, if you drop a big infodump of the world's setting, or the way machines work, or how various monsters are classified, etc., it won't be believable because there's no reason for the character to think things they already know. You could show them working through various possibilities in their mind, coming to correct conclusions, that kind of thing, but the process has to appear honest. Always assume your reader is intelligent, and is capable of sensing expositional shortcuts.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Writing exposition can be a difficult balancing act to master. It can be tempting to get your exposition out of the way with an extended monologue or description, but there’s nothing more off-putting to readers than a plot dump. Ideally, you want to slowly weave exposition into your prose in a way that feels natural.

To learn more, read our full guide on exposition here.

🧙 Example: The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

The worldbuilding in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings series has captured readers' imaginations for almost a century now, and much of that is thanks to Tolkien’s exposition expertise. In the opening of The Hobbit, Tolkien deftly introduces the world of Middle-earth, the peaceful setting of the Shire, and Bilbo Baggins' relatively uneventful life:

“The Bagginses had lived in the neighbourhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but also because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him. This is a story of how a Baggins had an adventure, found himself doing and saying things altogether unexpected. He may have lost the neighbours' respect, but he gained-well, you will see whether he gained anything in the end.”

Tolkien keeps the tone light and whimsical, which helps draw the reader into the world without overwhelming them with information.

Inciting incident

Once you’ve established the status quo, it’s time to tear it apart! The inciting incident is the event that kicks your story into gear — it’s the catalyst that thrusts the protagonist out of their ordinary life and into the extraordinary. This incident sets up the conflict and tone for the rest of the narrative going forward — so if you can nail this plot element, you’ll have your readers hooked from the get-go.

Q: What is the biggest mistake writers make in their opening chapters?

Suggested answer

The biggest mistakes I see in the opening chapters of new authors are:

- Spending too much time on backstory that is not needed in the present moment or in the opening situation the book starts with. Any backstory information that is crucial to the story should be woven into the narrative as the story goes along or introduced after the initial inciting incident. The reader needs to know enough about the character to care about what happens to them and to begin rooting for them, but they don't need to know their entire life's story or all of the characters that occupy their world.

- Not providing enough information to give the story a sense of place, especially in stories that do not take place in the present day. In historical, sci-fi, and fantasy, there needs to be some time spent in world-building by placing descriptive sentences here and there in the opening. For instance, stating that someone is traveling in a carriage denotes a historical novel. Traveling at light speed in a spaceship evokes images of sci-fi and perhaps another planet or world. So be sure to place your characters in this new world right away.

- Not starting to move quickly enough into the inciting incident or the catalyst of the story, and spending too much time on non-consequential details like gardening, eating, riding a bike, brushing teeth, etc. There needs to be some type of action and some sort of trouble within the first 12,000 - 13,000 words. This is a good benchmark to shoot for as far as having your inciting incident occur by this point in the story.

You may have to try a few ways and experiment with different points in time as far as where your book needs to start.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Your first chapter has a lot of work to do. It needs to engage readers straight away, and by readers I mean everyone from a literary agent's assistant to a commissioning editor, a book marketer, or someone in a bookshop idly picking it up. That means something has to ignite in those first few thousand words, whether a plot, a question or a voice.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

While there’s no hard-and-fast rule, you should typically aim to include your inciting incident within the first 10% or so of your story. Readers want to get to the meat of your narrative, so it’s better not to make them wait around for too long before the action kicks off.

To learn more, read our full guide on the inciting incident here.

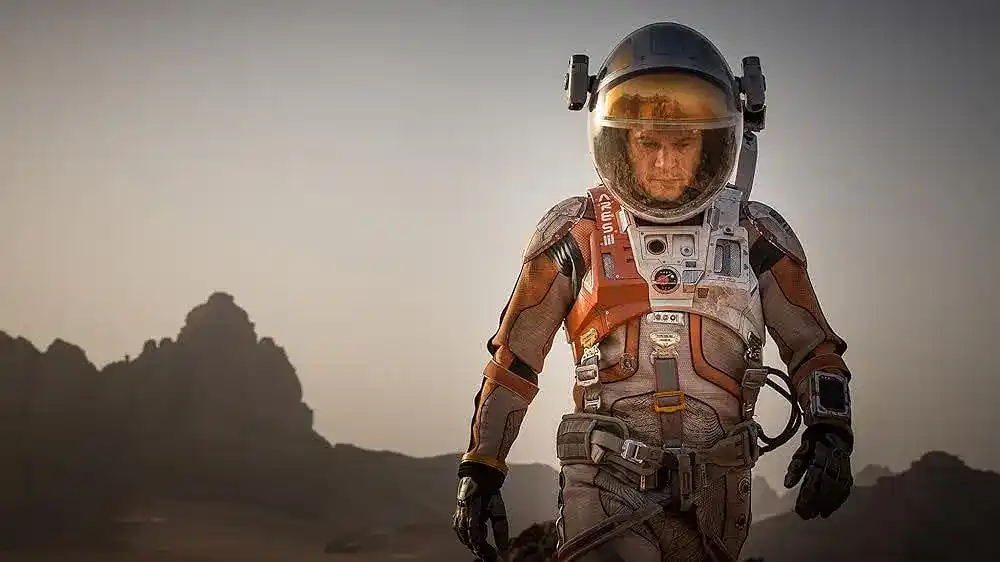

🚀 Example: The Martian by Andy Weir

The inciting incident in The Martian is straightforward and effective — protagonist Mark Watney is accidentally left behind on Mars after a mission goes awry. Watney goes from a member of a distinguished space crew to a lone survivor on another planet, setting the stage for his signature sardonic commentary on everything from growing potatoes in his own waste to becoming Mars' first space pirate.

Rising action

If the inciting incident kicks off your story, and the climax is the dramatic crescendo where the tension peaks (more on that in a bit), the rising action makes up everything in between — therefore accounting for the majority of your story.

Think of the rising action as a series of challenges that your protagonists have to overcome: each one should get progressively more difficult, upping the ante until the tension reaches a boiling point. Each challenge should be meaningful for your protagonists’ progression in some way, whether it presents difficult choices, explores character flaws, or reveals plot-altering information.

As the plot element that makes up by far the largest part of your narrative, many writers find the rising action to be the most fun to write, but also the most difficult. It can be particularly tricky to nail the pacing — move too fast and your story will feel rushed, but too slow and you risk losing your readers’ interest. To keep your pace consistent, try to incrementally increase the scope of each challenge, with each one building naturally on the one that came before.

To learn more, read our full guide on rising action here.

👁️ Example: 1984 by George Orwell

Winston’s path to rebellion starts out slowly in 1984, with his purchase of a simple diary for him to air out his unfiltered thoughts. The scale of Winston’s transgressions grows gradually throughout the rising action; forbidden conversations lead to a passionate love affair, before he finally dares to join the resistance movement. With every step Winston takes towards sedition, the stakes get a little higher, and we watch as he transforms from a silent dissenter to an active rebel.

Climax

The climax is the top of the mountain — it’s the culmination of all that tension you’ve carefully constructed throughout the rising action. This element is typically incorporated towards the end of your story, and often places your protagonist at the crossroads between victory and defeat.

To make your climax hit home, try to intertwine the conclusion to your story’s external conflict with your protagonist's internal journey. This is where your characters are going to be faced with their most difficult choices, after all; resolving all your main plot threads in one fell swoop will make those resolutions feel so much sweeter.

Q: How can authors effectively build tension leading up to the climax?

Suggested answer

Well, the main method is to up the stakes as you go along. The more it matters emotionally to the characters and externally to their circumstances and the world around them, the more important that climax becomes. Every time you increase the stakes, the anticipation of readers goes up surrounding the climax and what might result. The final confrontation between hero(es) and villain becomes and edge-of-the-seat affair.

If you struggle with this, the technique I recommend is to examine the plot questions asked and answered. All plots are effectively a series of questions asked and answered. When you ask and how soon you answer is part of building tensions. Some questions carry over several scenes, some are answered right away. Some last whole chapters or several chapters. Some are asked at the beginning and not answered until the end, like the main driving core quest question of will good conquer evil? Will the protagonist get what he or she wants or needs? Will the villain prevail?

Make sure you are answering the questions you ask in appropriate places. Yes, you may want to set up a sequel and leave a few things hanging but the trick is to pick the right questions. The rest need to be answered, and figuring out which questions depend upon that climax and asking more and more of them as you lead up to it is a really great way to increase suspense and anticipation and lend that sense of urgency to the climax that keeps readers turning pages and dying to know what happens.

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Stakes need to be continually raised as the story builds to a climax. The problem[s] should be getting more and more difficult until the climax is reached.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Subtle foreshadowing is a solid way to build tension. Hinting at what's to come can prime the reader for the climax without revealing exactly what's coming—just that something is coming.

Well-written, lower-level conflicts between characters is another effective tool to build tension: short arguments, occasional emotional blow-ups, etc. These are, in effect, a kind of foreshadowing themselves, setting the reader up for the finale, whatever it may be.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In most stories, readers are likely to have a good idea of what the ultimate conclusion will be — the heroes will slay the dragon, the star-crossed lovers will confess their feelings, or the mystery will be solved (sometimes all three). However, it’s less about the what, and more about the how; ideally, a climax should feel both inevitable and unexpected. Every major decision, piece of character development, and subplot should come together to make this moment feel earned and satisfying.

To learn more, read our full guide on the climax here.

🤖 Example: Return of the Jedi (1983)

Even as the fate of the Rebellion hangs in the balance, the core tension in the climax of Return of the Jedi comes from Luke’s inner struggle to maintain his faith in humanity and resist the temptation of the dark side. Everything comes to a head when the Emperor forces Luke to choose: give in to hatred and save his friends, or stay true to his principles even at the cost of his life.

Luke’s refusal to fight is what finally moves Vader to turn against the Emperor, which ultimately seals the victory for the Rebel Alliance; in other words, the resolution to Luke’s internal dilemma is what helps resolve the external conflict as well.

Falling Action

Once the dust has settled, the falling action is a satisfying wind-down for your readers to process the events of the climax. This is the time for you to explore any ripple effects from your climax, how other characters have been impacted by the changes, as well as any unintended consequences that emerged from your protagonist's actions.

The falling action is also your opportunity to tie up any loose ends in your subplots that weren't directly connected to your main conflict. Of course, sometimes less is more — leaving a select few story threads open gives readers room to speculate on what might happen next.

🦁 Example: The Lion King (1994)

Following Scar’s dramatic defeat, the audience is treated to a cathartic scene that showcases the aftermath of Simba’s victory: the hyenas are banished from the Pride Lands, and the once-barren wasteland begins to bloom with life and vibrant color once again. The animals of the Pride Lands are able to look to the future with renewed hope now that their rightful King has returned to the throne.

Dénouement

The falling action is closely tied to the final stage of the plot diagram: the dénouement. Though they are often grouped together, the two are their own distinct plot elements.

While the falling action contains the immediate consequences of your story’s climax, the dénouement is the final narrative beat where you show your readers what the new normal looks like. Think of it as the cherry on top of your storytelling sundae: it’s there to tie everything together and leave the reader feeling satisfied.

Q: What strategies make a redemption arc feel earned, credible, and emotionally powerful?

Suggested answer

I'd say the main thing here is to stay true to the character. The redemption has to feel authentic based on how the character's been presented thus far in the book/story. Keep in mind the character's past actions and reactions as a whole. Because in the end, if the redemption feels like it's been shoehorned in or has come out of left field, the reader will feel that. However they redeem themselves, it has to feel like something that specific character would do—not just any character who's gone through the things they've gone through, but that character in particular. As for impact, the more three-dimensional the character is, the stronger the impact will be when their redemption comes about, so making sure they have a well-rounded, more-than-surface-level personality is absolutely key.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Just as in real life, sometimes people have to hit rock bottom before they change and accept that they are an addict or an alcoholic, etc. So if possible, you want to show this character having some sort of reason to see that they need to change. Perhaps their negative actions have impacted someone dear to them, and they feel regret or remorse, which then motivates them and serves as a catalyst for change.

There should always be reasons why characters act the way they do, whether positively or negatively, and a sort of "awakening" might be a good idea if they must change their stripes for this change to feel organic and not forced.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Like the exposition phase, it’s best not to let the dénouement drag on for too long — you should aim to resolve your story while the emotional impact of your climax is still fresh. A good rule of thumb is to let the dénouement reflect the scope of your story. Longer narratives juggling a few elaborate plot lines and character arcs may need multiple scenes to wrap everything up satisfyingly, while shorter stories might only need a paragraph or two.

To learn more, read our full guide on dénouement here.

⚖️ Example: Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

After Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy clear up their mutual misunderstandings and confess their love, Austen provides a peek at what lies ahead for the happy couple: the marriage improves the Bennets’ circumstances, and the pair enjoy a happy life together. Elizabeth’s sister Jane moves to a nearby estate with her betrothed Mr. Bingley, allowing the sisters to remain close, while Lydia and Wickham live a less prosperous life marked by financial instability.

In keeping with the rest of the novel, Austen keeps the resolution light-hearted, leaving readers with just enough context to feel content.

How to create your plot outline

Now that you understand the importance of plot elements and how to use them to write a strong story, it’s time to get planning! If you’re looking for a tool to map out your story from exposition to dénouement, check out Reedsy Studio — our free all-in-one writing app.

Q: What outlining techniques can 'pantsers' use to guide their storytelling without stifling creativity?

Suggested answer

Even having a very basic three-part/three-act overview of the story with just one page of notes per act will help you stay on course when drafting, so the finer details can emerge while you write. You want to know at least how the story ends, and then drive forward toward that ending. The ending doesn't have to be too specific, again, as details may arise while crafting the story, but knowing if it will be a tragedy or have a positive outcome at the end should help to drive the narrative forward.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Here’s how you can use it to plot your own story.

Plotting with Reedsy Studio

First off, we’ll need a story to plot out in Studio. In this tale, we’ll be following a lonely inventor named Theo and his recently developed household robot, Iris. Let’s start by creating a book in Studio.

Once your book has been created, you’ll find a list of Boards on the left hand side. You can create Boards for worldbuilding, character profiles, story bibles, or anything else you can imagine! In this case, we’ll be using a Board to outline our plot.

Our planning Board looks a little lonely, so let’s add a Note for each plot element we’ve discussed in this post. Notes are exactly what they sound like — convenient cards you can use to organize information.

Related Notes can be grouped together into folders so you can keep them all in one place, like so:

Within each Note, you can add Attributes to expand on the details. The more Attributes you add, the more detailed your plan will be, and the more reference material you’ll have available for when it’s time to start writing.

For more information on how you can use Reedsy Studio to help you plan your novel, check out this post.

You don’t need to worry about jumping back and forth between your Notes and your manuscript when you start writing — you can pin a Note to the right-hand side of your screen for easy access, like so:

FREE WRITING APP

Reedsy Studio

Set goals, track progress, and establish your writing routine in our free app.

There you have it — everything you need to know about the elements of plot, from exposition to dénouement. While a plot diagram might provide a helpful structure to help you map out your story, remember that it’s just a framework; it’s what you choose to do with each element that will make your narrative truly unique.