Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

What Is a Tragic Hero? Definition, Examples & Common Traits

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →If you’re looking for a character type with a serious literary pedigree, look no further than the tragic hero. From the Greek theatre to Shakespeare to the Star Wars prequels, these unfortunate protagonists populate some of the most memorable stories ever told. With this in mind, let’s furrow our brows, dust off our prop skulls, and peel back the tortured layers of this complex character type.

What is the definition of a tragic hero?

In literature, a tragic hero is a character with heroic or noble traits, but also a fatal flaw that ultimately leads to their downfall. This flaw could be anything, from pride or vanity to excessive curiosity or jealousy, but it will always lead to the character’s demise, whether literal (i.e. death) or metaphorical (losing their position or reputation, for example).

Aristotle’s tragic hero

In his treatise Poetics, published over 2,000 years ago, the ancient philosopher Aristotle first defined the concept of a tragic hero, outlining characteristics shared by all protagonists of classical tragedies (see the next section for these).

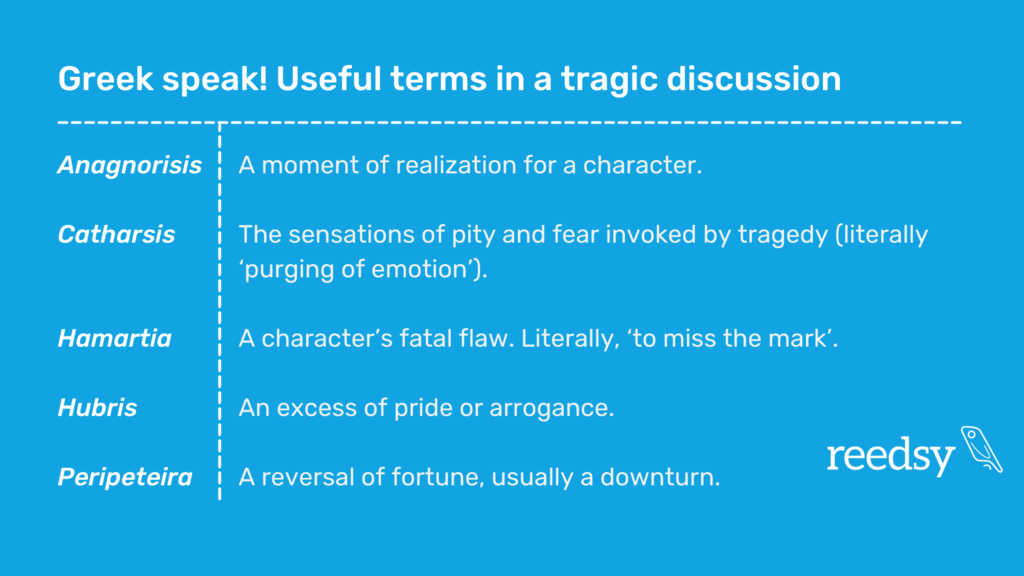

Aristotle believed that tragedy, above all, should invoke catharsis in the audience, allowing them to experience fear, pity, and awe while watching the misfortunes of the tragic hero unfold. This, he believed, would purge the audience of extreme emotions within a controlled environment and, in turn, give way to relief.

Don’t mess with the gods (and other useful lessons)

Tragedy was also meant as a tool to educate the people on the realities of life and, in particular, the relationship between men and gods. Often, a tragic hero’s downfall was a result of them disobeying a god or believing they could subvert the gods’ will (damn you, hubris!).

The great tragedians showed audiences that a sudden downturn in fate could happen to anyone who defied the will of the gods and other superiors. By punishing characters who rose above their station and flaunted their hubris, tragedy imparted a powerful lesson about the mutability of human fate, and the importance of respecting the status quo. After all, if great kings like Agamemnon could be thrown from their pedestals by tragedy, what’s to stop that from happening to the average Joe (or average Jason, if they were Greek)?

What are the characteristics of a tragic hero?

Tragic heroes don’t have to be ancient Greek kings and princesses. They come in all shapes and sizes and can appear in any genre. Here are a few characteristics commonly found in tragic heroes:

They’re usually a pretty good person

They won’t be perfect (that’s kind of the whole point), but tragic heroes are typically well-intentioned people with a solid moral compass. Their motivations should be relatable, even if they are sometimes misguided.

They start their story doing well

The reversal-of-fate coming in the plot means the character has to start out doing pretty okay. While they’re not always the literal king (a la Oedipus), they’re usually comfortable and happy.

The audience must root for them

Their virtues are clear enough that the reader or audience is on their side and experiences sympathy for the hero when things start to unravel. Indeed, the audience has to root for them for a tragedy to work: if they disliked them, their unhappy ending wouldn’t be, well, tragic!.

But they have that pesky fatal flaw...

There are a variety of possibilities for what that flaw might be (we’ll give you a few examples later in this post), but this is an essential, non-negotiable element of being a true tragic hero. Aristotle referred to this fatal flaw as a hamartia.

Not sure what fatal flaw to give your tragic hero? Check out our list of 70 fascinating character flaws for inspiration!

Their downfall is (kind of) their own fault

All tragic heroes must have a peripeteia, a sudden reversal of the hero’s hitherto good fortune. These bad things don’t usually just happen to them at random. There should be a connection between their own innate failings (their hamartia) and the misfortunes they suffer — even if that connection is a complex one.

Their punishment isn’t always fair

For example, having all of the ills of the world unleashed upon you and going down in history as the source of mankind’s undoing is a pretty harsh sentence for just being a little nosy, but that’s what happened to Pandora. In these stories, the punishment rarely seems to fit the crime, and the reader is left wondering whether the hero really deserved the consequences meted out to them — making their fate all the more tragic.

They become more self-aware over the course of the story

The tragic hero recognizes the error of their ways, usually after they’ve hit rock bottom as a consequence of them. This moment of recognition is a hallmark of the tragic hero’s personal journey, referred to by Aristotle as the anagnorisis. Unfortunately, this self-awareness usually comes a little too late.

They don’t get a happy ending

A tragic hero, true to their name, doesn’t run off into the sunset in the end. They may have some kind of satisfying conclusion as they experience growth or come to terms with the new state of affairs, but their downfall is an irreversible one.

Free course: Character Development

Add depth to your characters and craft that perfect hero... or villain! Get started now.

What’s the difference between a tragic hero and an anti-hero?

There’s often confusion between tragic heroes and anti-heroes. Both are interesting and complex character archetypes — however, these two terms aren’t interchangeable, and denote very different types of characters.

In basic terms, the anti-hero is someone who, despite being the hero of a story, distinctly lacks heroic qualities. They might do good things, but not necessarily for good reasons. On the other hand, the tragic hero is generally morally righteous and heroic, except for their fatal flaw. Their intentions are generally noble, while the anti-hero’s usually aren’t.

If an anti-hero sounds more like what you’re looking for, you can check out our definitive guide to anti-heroes.

5 tips for writing a great tragic hero

If you’re currently developing your characters and are interested in writing a tragic hero into your story, here are a few tips:

1. You don’t have to stick to the formula exactly

Writing isn’t always about following the rules! For example, if you want to give your tragic hero another reversal of fate from bad back to good, or have them realize they aren’t the only one to blame, go for it — subverting the formula and surprising your audience can be a great plot twist!

2. Show the tragic flaw — don’t tell it

This tip goes for pretty much anything you write. Instead of telling your readers that your hero is stubborn, show examples of them behaving that way. The golden rule of “show, don’t tell” will make your writing more interesting and encourage your readers to do the work to figure the character out!

🦸♂️ Find book coaches and editors who can help you write your tragic hero:

Crystal B.

Available to hire

I write and edit award-winning children's books for publishers. I coach aspiring writers to help them create a professional manuscript.

Conni M.

Available to hire

Nonfiction expert / former Editor-in-Chief and professional book editor / create a book that builds your business & reputation

Britny P.

Available to hire

Britny (she/they) is a YA fiction and pop culture non-fiction editor with over 7 years of traditional publishing experience.

3. Align your hero’s arc with your story structure

If you’re planning on incorporating the classic tragic story beats (e.g. establishing the status quo, a reversal of fate, a moment of realization when your hero is at their lowest, plenty of dramatic irony), make sure you think carefully about when it’ll be most effective to deploy those moments. If you don’t, you might find your plot's narrative high point comes too early after the rising action or falls flat. It can, therefore, help to figure out your story structure ahead of time.

4. Carefully construct your hero’s backstory

Giving your character a fatal flaw is a good start in making sure they’re fully fleshed out, and therefore more memorable. But don’t stop there! You can add even more depth to your character by creating a backstory that supports their flaw, as well as considering their other personality traits. Filling out a document with character attributes or a character questionnaire can be helpful with this.

5. Don’t neglect your antagonist

Just because you’ve got a super interesting protagonist doesn’t mean you can have a boring villain. In fact, since your protagonist is morally grey themselves, writing a foil to a tragic hero lends itself well to complex and interesting antagonists. Whether you include an ambiguous antagonis, a friend-turned-foe, or any other variant, give them enough depth and create a worthy adversary for your tragic hero.

For more tips on how to write a great villain, you can check out our video on the topic below!

Examples of tragic heroes in literature

Warning, spoilers ahead!

Oedipus (from Sophocles’ Oedipus the King)

Where they start: At the start of the play, Oedipus is the king of Thebes. At the very top of society, he’s a little full of himself, but overall a good person.

The fatal flaw: His hubris in believing that he can fight his destiny.

What went wrong: For his whole adult life, Oedipus, a foundling who became king, had a prophecy looming over him: that he would bed his mother and slay his father. He discovers that as a result of his arrogant efforts to subvert the course of the future (never a good idea in Greek mythology), he has unwittingly married his mother and murdered his father. Whoops!

Where they end up: He is driven mad by the revelation and blinds himself.

Antigone (from Sophocles’ Antigone)

Where they start: Before the tragedy, Antigone is the loyal and high-born sister of not just one, but two kings.

The fatal flaw: Her stubbornness.

What went wrong: Antigone’s brothers die in battle as they fight over the throne left vacant by their father. She obstinately defies the new king’s orders to leave her traitorous brother’s body unburied on the battlefield as a mark of disgrace.

Where they end up: Her stubborn loyalty is punished brutally, and she is buried alive.

Jay Gatsby (from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby)

Where they start: Gatsby, a mysterious millionaire, throws lavish parties and is (superficially) popular and well-regarded by Long Island’s social elite.

The fatal flaw: His obsessive and delusional love for his former sweetheart, Daisy.

What went wrong: Gatsby embarks on an obsessive campaign to win over the now-married Daisy Buchanan. Initially tempted, Daisy ultimately leaves the overbearing Gatsby, returning to her (equally overbearing) husband. His obsessive behaviour not only pushes Daisy away, but invokes the ire of her husband.

Where they end up: Gatsby refuses to give up hope, but a convoluted case of mistaken identity (and the spite of Daisy’s husband) leads to Gatsby’s lonely death at the hands of a man he’s never met.

Macbeth (from Shakespeare’s Macbeth)

Where they start: Macbeth is a brave and loyal general serving under King Duncan.

The fatal flaw: His ambition.

What went wrong: After learning (by way of prophecy) that he will one day be king, Macbeth is gripped by an urge to claim his crown sooner rather than later. He commits regicide, killing his friend King Duncan, and his growing paranoia leads him to murder several others to cover up the betrayal.

Where they end up: Eventually, his crimes catch up to him and his wife: Lady Macbeth dies by suicide as a result of her own guilt, while Macbeth is killed by the avenging hero, Macduff.

Emma Bovary (from Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary)

Where they start: Emma is married to a well-meaning, if somewhat naive, young man.

The fatal flaw: Her desire for romance and luxury.

What went wrong: Having grown bored with her slow married life, Emma seeks excitement elsewhere. She indulges in love affairs and a new-found extravagant lifestyle, which eventually leaves her in debt.

Where they end up: When those debts begin to be called in, Emma realizes she has nobody to turn to; even her lovers will not help her and, in a fit of despair, she ends her own life.

Okonkwo (from Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart)

Where they start: Okonkwo is a famous wrestler, a powerful warrior, and the leader of his village. He has the power and influence he craves over his community.

The fatal flaw: His fear of appearing weak and ending up like his father.

What went wrong: When an Oracle proclaims Okonkwo’s adoptive son should be killed, the elders advise him not to participate in the killing himself. However, Okonkwo’s obsession with masculinity and fear of being perceived by his fellow mean as weak leads him to take part in the murder. Having offended the gods and spiralling into guilt, Okonkwo accidentally takes more lives, and is sent into exile.

Where they end up: After suffering several more years of hardship as a result of his choice, Okonkwo eventually kills himself to avoid any further humiliation, a final enactment of his all-consuming pride.

Eddard Stark (from George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones)

Where they start: Eddard (Ned) is the respected Lord of Winterfell, a loyal friend of the king, and a loving husband and father.

The fatal flaw: His obsession with honor, and failure to adapt.

What went wrong: Ned’s innate sense of right and wrong causes him to make several missteps as he navigates the court of his friend Robert. After falling foul of the king’s duplicitous wife, Cersei, and threatening to expose her children as illegitimate, his desire to do right by his friend and bring the betrayal to light puts him in a precarious position.

Where they end up: His refusal to give up his principles and adapt to the times lead to his execution after King Robert dies, leaving nobody to protect Ned from Cersei.

Elena Richardson (from Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere)

Where they start: Mrs Richardson starts the novel with a picture-perfect life: she’s wealthy, successful, and has every aspect of her life in meticulous order.

The fatal flaw: Her desire to maintain the status quo.

What went wrong: Threatened by the arrival of a new family in the area that her kids befriend, Elena becomes consumed with jealousy, leading her down a dark path of suspicion and blackmail. Her need to follow the rules to the letter, to keep things just as they are, and her attempts to keep her children close eventually have the opposite effect, as her behavior drives them further from her.

Where they end up: The novel ends with Elena’s worst fear realized as her youngest daughter, Izzy, sets the family home alight and runs away.

You might feel a little down in the dumps after hearing all these tragic fates — but fear not! Unlike our tragic heroes, this crash course in tragedy does have a happy ending, because we’ve got even more resources to recommend.

You can check out our guide to Freytag’s pyramid, a dramatic structure designed with tragedy in mind, for more insight into how to write a great tragic arc!