Landing a traditional publishing deal is hard. Many of you write books out of a personal passion for your subject, maybe writing in general. You have research skills, some facility with language, you can write persuasively — you know how to borrow storytelling elements from fiction to suck readers into your narrative. But publishers also need authors to have business skills to help them position and sell their books. And that is not fair.

It's like asking Alex Morgan to be good at soccer and analyzing viewership trends for developing World Cup marketing campaigns. Unfortunately, it's where the industry is at right now and it's not likely to change anytime soon.

So hopefully this presentation will help you understand how to make the business case for your book more effectively. I'll just note before we get too far in, not everything I say will apply to every nonfiction project. That's just the nature of tossing in spiritual books and philosophy, biography, history, and photography altogether — it's just a really big bucket that we call Nonfiction. There are some differences, and I think Google is your friend, as well as writing groups and conferences, but do your research and take everything I say here with a little bit of salt.

How is querying nonfiction different from querying fiction?

With nonfiction, your authority matters as much as the writing. With fiction, authors can stand more in the shadows of their writing. Nonfiction queries should have a thesis. A ‘why it matters’ message.

By contrast, fiction queries tend to focus more on describing what happens. The plot summary is more necessary than why it matters. The ‘why it matters’ message for prescriptive nonfiction like cookbooks or self-help books, can be about improving readers' lives.

And with narrative nonfiction like history or biography, it tends to be more about helping the reader understand the forces that have shaped their world, or will shape their world going forward. That's kind of a broad generalization, but that's kind of apt for most projects.

Nonfiction queries also need a book proposal to accompany the query letter. Whereas fiction queries usually just need the query letter. And that's because fiction is usually sold based on a complete manuscript. You generally don't need that for nonfiction. You just need one to two really good sample chapters. There is an exception to that, most memoirs are sold based on a complete manuscript. It gets treated a bit more like fiction there.

Breaking down the query letter

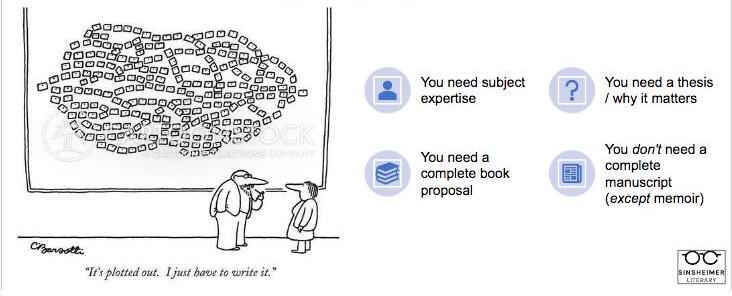

There’s definitely a strong networking component to publishing. A lot of my authors are referrals from existing clients. I thought it would be helpful to review a really excellent query letter that I received from the proverbial slush pile. I didn't know Craig until I received this email, and I signed him the next week. Let's dissect why and try to get specific.

Personalization

Dear Mr. Sinsheimer,

I am contacting you because you stated on MSWL that you’re interested in food- and place-specific narratives. You also mentioned on your agency website that you’re looking for books that focus on environmental issues. I think my cookbook, New England Soups from the Sea, fits those categories quite well.

Out of common courtesy, the most basic bar you need to clear with agents is to use their name correctly — assuring them that you chose to reach out to them specifically.

This is probably advice you've heard before, but don't write “Dear Agent”. Don't write “To Whom It May Concern”. Don't just launch in without a greeting either. Do some light stalking. Look at other books that this agent has represented that you like, or think about how your book fits into their expressed interests in terms of what they want to acquire going forward. In short, find something to admire.

I have definitely seen authors go overboard with the flattery. My manuscript wish list bio has a photo of me eating ice cream. And I've had a lot of authors open with complimenting me on my choice of a waffle cone. Which feels a little much. But listen, agents are human — err in the direction of flattery. So you can see in his greeting that he read my manuscript wish list. He knows that I'm interested in food and place-specific narratives. He also looked at my agency website — he knows I'm interested in environmental issues. And his project fits my interests. Okay, bar cleared.

Hook / Thesis

Because what if part of the solution to overfishing our oceans was to make seafood soups?

A good hook tells me the core concept as concisely and compellingly as possible. So in Craig's case, it reads like a thesis. A “why it matters” statement. What if part of the solution to overfishing our oceans was to make seafood soups? Tell me more, Craig.

This is the hardest part, the hook. This is really difficult for authors because to distill your precious 300 page baby down to a line is a challenge. And I always expect to have to rewrite the hook before submitting to publishers. But I do need authors to give it their best shot. If they go straight into a description of their book it tells me that they aren't sure what makes their book interesting to readers. Then that makes me worry that they don't know their audience. Or worse, they might have a Field of Dreams fantasy — if you write it, the readers will come.

If you've done a little bit of research, you know there's something like three million books published in the U. S. alone each year. Two million self-published, about a million published by traditional publishers. And books don't just break out because you happen to write it. You have to really know your audience. Which is why I really like this concise, and compelling statement.

Evidence of need

Consider that 90% of seafood consumed in America is imported, often from unsustainable sources. And yet, few Americans are aware that our national fisheries are the most sustainably managed fisheries in the world, ensuring clean waters and thriving fish stocks.

Two of the most important questions your query letter and book proposal need to answer are “Why this book?” and “Why now?”

You need to find a way for the publisher to tell the media and readers, “Hey, pay attention. This is important.” If you read Craig's next paragraph here, what the importance, what the evidence of need is, is America imports 90% of its seafood from questionable sources, but we have really healthy and sustainable domestic fisheries. We need to change habits. His cookbook is squarely aimed at doing that.

So my caveat is that I think many authors confuse a market gap with evidence of need. Just because a topic hasn't been written about in a book doesn't mean it needs to be. Some things people just don't want to read about.

I see a lot of biographies with really minor historical actors. People will pitch me the first biography of the Secretary of Commerce under President Taft or something. It's not likely to sell, except maybe to a narrow slice of historians. So you have to pair that evidence of need with a receptive audience. Some proof of market.

Book description

New England Soups from the Sea will be the first cookbook solely on the seafood soups of New England while also promoting a message of sustainability, environmental awareness and support for our national fisheries. It will include 80 recipes for broths, chowders, bisques, boils and stews. You might say it’s as if The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan met the renowned seafood chef and cookbook author, Barton Seaver.

You might also ask, “Why just soups?” First, they are a way to make seafood more accessible to the average American. Most of my recipes are very simple and have a broad appeal, such as chowders. Second, New England seafood soups are a unique point of differentiation to other seafood and New England-themed cookbooks. And third, I live in New England and see a void in the cookbook market for this subject.

The thing to remember with how you describe your book in a query letter is that a query letter is just an appetizer. The book proposal is the entree. You don't need to cover everything in your query letter. And if you just say enough to get the agent interested, I promise they will read the full overview, the chapter outline, and descriptions. You include all of the meat and potatoes of what your book will be in the book proposal.

So think no more than two paragraphs. Remember, you have to keep your query letter to a page. And if you look at what Craig's letter tells me about the book, it's not a ton, right? I know that it will have 80 recipes for broth, chowders, bisques, boils, and stews. I know the recipes are intended for home cooks and lean towards accessibility. I know there's a sustainability throughline. That's enough. Once I get into the proposal, I'll find out, for example, whether he features that message of sustainability mainly in the recipe headnotes — or if he has devoted background chapters to help readers understand the issue of overfishing. He doesn't need to explain all that. I'll see it and find out.

Expertise & platform

Finally, I bring a unique perspective as a former Nutritional Therapist. For years I specialized in gut health and I’ve become an authority on making homemade broths and soups via my active food blog, www.fearlesseating.net, and my three self-published books—The 30-Day Heartburn Solution; Fearless Broths and Soups; and The Thai Soup Secret. They have earned me close to $60,000 and continue to sell well on Amazon’s platform.

The next part is we have to know that this author is the right author for this book. And with this next paragraph, I start to get a sense of who Craig is. I know platform is a scary concept, and I don't remember who said it — it might have been Jane Friedman, who has some wonderful resources for authors — but platform is really just your access to the reader's attention. That access is built both on your direct following, such as the number of subscribers to your newsletter, or listeners to your podcast, or people who have attended your talks. But also your indirect potential following through your helpful connections.

So let's look at his expertise. Craig has already written three books on soups. He's got credentials as a nutritional therapist. That seems pretty solid to me. I don't question why he's writing this book. For his direct access to readers, he's got an active blog. He's got an author website. Presumably, some of his readers of his previous three books will also buy his fourth book. So it might look a little bit crass that he included the sales figure, but he says he's earned $60,000 as a self-published author. Honestly, I found it helpful.

If I do a little bit of quick math, I guess he sold around 6,000 books. Maybe even 10,000. $10 to $20 bucks a book, maybe about 2,000 copies per book? You know, I can work with that. It's not overwhelming, but he didn't sell his book to his six best friends and his extended family. You know he sold it to the public.

Finishing like a pro

As requested, attached is my full proposal as a PDF. It includes two sample chapters and some sample recipes. In it, you’ll also see I have a detailed promotion plan and have secured cover endorsements from the president of the Weston Price Foundation, Sally Fallon, as well as acclaimed chefs and authors Jeremy Sewall and Barton Seaver.

Thank you so much for your time and consideration!

Craig Fear

This next slide we'll see his indirect potential following, the connections he can lean on for book promotion. This paragraph, for me, tells me that Craig is a professional. I want to work with authors who are professionals. It makes my job easier because I don't have unlimited time. I want to work with authors who know what they're doing. I don't mean by professional that he's a ‘professional author’. Most of my authors have day jobs. They're academics, they're journalists, they're chefs. I just mean that he knows what is expected of him from agents and editors.

So let's ask “why does that paragraph tell me that?”. One, he read and followed my submission guidelines. That's kind of the basic one. He knows from my submission instructions on my page, that I ask for book proposals to come in as PDFs. And the reason I do that is because I like to be able to open them and read them wherever I am. Whether it's on my phone or my laptop, I find it easiest to do that on a PDF.

The next one is more nuanced. He has a promotional plan that includes the fact that he already went out and got great endorsements already. If you get an influential endorsement early, it sort of eliminates any doubt in my mind that your connections are real. And editors love to see it because these early endorsements can easily become back cover blurbs later with the person's permission.

So, I didn't actually know Jeremy Sewell but I definitely knew Barton Seaver, and that caught my eye. He had already had a quote from Barton. This is the time to call in favors. Put aside your bashfulness. Now you don't necessarily need to get these endorsements at the proposal stage, but I do think they help. You definitely need to think through who you know and how they might be helpful to you in promoting the book.

This is just a page but it hooked me enough to have a phone call with him a week later and sign him.

The Dreaded Book Proposal

The book proposal. It helps flesh out the book, who will read it, and how the author can help the publisher get it into those readers hands. It's a business plan and it usually consists of the following sections:

- An overview of your book summary.

- Identification of the likeliest readers and why.

- A plan for how you can help the publisher promote the book to those readers.

- A few related titles and analysis that shows how your book differs from or improves upon those works.

- Your author bio or “About the author” section.

- A table of contents and descriptions of each chapter. This probably shouldn't be too long, but a paragraph, two, maybe three paragraphs. Something that says you've actually put thought into what each of those chapters will look like.

- One to two sample chapters.

I'm not going to go through every section of the proposal, but I did want to focus on a few areas I think authors really struggle with the most. And the first is the target audience or market analysis.

Target Audience

There are two types of target audiences, broadly speaking, depending on whether your book is more prescriptive or narrative.

The first is people whose problem you are solving. As an example, I sold a book called The No Nonsense Guide to Divorce. It was aimed at divorcing millennials. The author convincingly argued that Millennials are entering their peak divorce years, and we're looking for advice on topics that traditional divorce literature omits. Like the use of co-parenting apps, how mediation works, what happens when unmarried partnerships dissolve. Just pragmatic advice. That felt like a book that was solving a real problem.

Then there are people who are readers because they have a passion for your subject, or for a closely adjacent subject. So here you might want to imagine you're at a cocktail party — whose eyes would light up if you described your book to them? Not the ones who would politely listen, but the ones who know something about the topic already and are jazzed to discuss it with you.

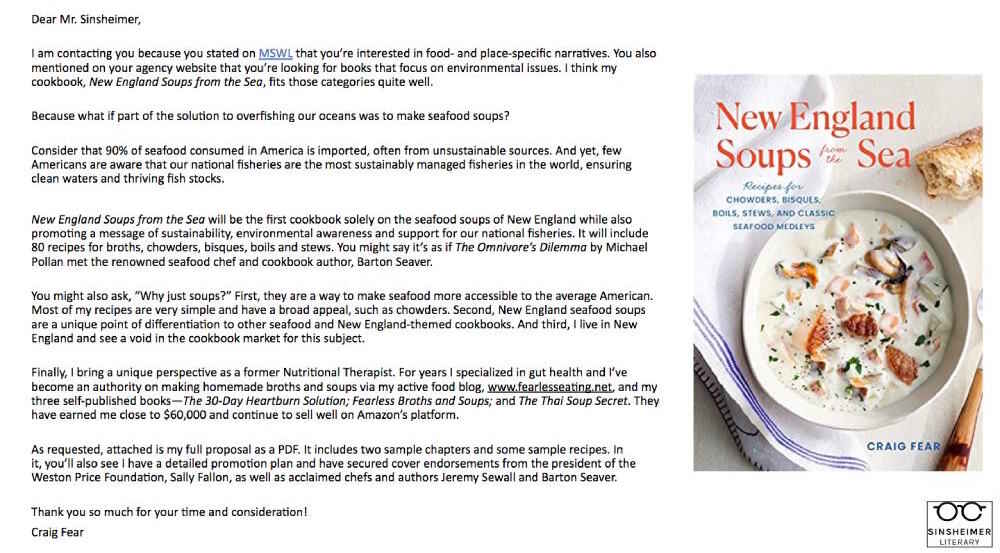

For example, I represented a maritime adventure memoir called All Hands on Deck. It's about the author's time as a carpenter on a replica 18th-century warship that he and a small crew sailed 5,000 miles from Rhode Island down through the Panama Canal over to California to film Master and Commander.

It's kind of this life-imitating-art situation where they hit a hurricane and they had a de-masting, and they almost sank, and they ran into these like real-world pirates in Panama. The point is that Will identified in the proposal two primary and overlapping audiences — the first were tall ship enthusiasts, many of whom belong to yacht clubs. And the second are Patrick O'Brien fans. If you don't know Patrick O'Brien, he was the author who wrote the maritime novel series that included Master and Commander. So now Will is on a really successful author tour. Which you’ve probably heard are not super common anymore. But shockingly, he is getting invited to speak at every yacht club and maritime museum in the country, and some in the UK.

So, that's a picture of him at the New York yacht club giving a talk to 350 people. All of whom bought the book. That's knowing your audience. It's not a huge audience, right? I think the last estimates I saw were that there are about 300,000 members of the Yachting Club of America, which is kind of like this big overarching club with many different individual yacht clubs in it. So it's not enormous. But those are passionate and, frankly, wealthy people.

So it's proven to be a really excellent audience. And I think that kind of narrow but deep audience tends to work the best. Whatever you do, don't just claim ridiculously broad readerships. “Women over 50” is not an audience. “True crime readers” is not an audience. You have to be more specific than that.

For example, you might say, “light true crime readers who enjoy stories of conmen operating in insular worlds like ‘the Billionaire's Vinegar.’ People who avoid the bloodier end of the true crime genre.” That's not even a perfect audience, but at least you're starting to get there.

You just really have to think and narrow it down. Because I get a lot of very data-centric submissions, but their data is about the American reading public writ large. It’s nice to know some recent true crime trends, but you have to visualize an ideal reader. That's not easy to do, but it's about specificity.

Are you an expert?

The next piece I wanted to point out is about expertise. One of the biggest differences between fiction and nonfiction is that the author's background and credibility really matters. With nonfiction, it isn't just about how well you write but also how much I trust what you're saying.

I want to preface this by reassuring everyone that I saw and loved Barbie but, for our purposes, Oppenheimer is a more useful example. So you might know that Christopher Nolan based Oppenheimer on a book called American Prometheus. The primary author Martin Sherwin, who was he? He was an academic who specialized in the development and proliferation of nuclear weapons. He taught at Princeton, UPenn, Berkeley. He established the Center for Nuclear Age History and Humanities at Tufts. And he spent two decades writing American Prometheus before eventually bringing in a co-author, a guy named Kay Bird, who had written a number of bylines that related to nuclear proliferation, to kind of help finish it. He needed some help with the writing.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is how you get Knopf to bite. And I know this sounds elitist, and you might think I'm telling you to stay in your lane, and you absolutely don't need a Ph.D. to write most nonfiction books. But I think it's worth being aware that the overwhelming bias in traditional nonfiction publishing is to sign books by people with some verifiable claim to subject matter expertise.

So if a tax attorney comes to me with a new theory of what killed the dinosaurs and he has no relevant degrees or publications in reputable journals, that's an easy pass for me.

And there are plenty of exceptions of authors kind of coming in from outside a field and shaking things up with a new perspective. I think of Rachel Carson, Silent Spring. I think she was a marine biologist. I don't think she had any knowledge of toxicology before she started realizing the DDT stuff.

It happens all the time, so take everything that I'm saying with a grain of salt. You will be better off and have a more realistic chance of a traditional publishing deal if you've spent the time to establish your reputation as an expert on the topic before you try to land a book deal.

But different kinds of books, different genres, require different levels of expertise. And some don't need it as much too. I don't know who wrote those Atlas Obscura books, but if you're writing about ephemera and oddities, and things like that, I don't know if you need to be an expert. But for many nonfiction books, you do need to have some reputation in connection with your topic area.

The last thing I'll say about this is “nothing succeeds like success”. It's way easier to get more latitude if this is your second or third book and your first and second did well. You'll have an easier time moving on to a topic in which you weren't necessarily known as an expert. If this is your first traditional book deal, you have to have some following, some reputation and authority that you can point to.

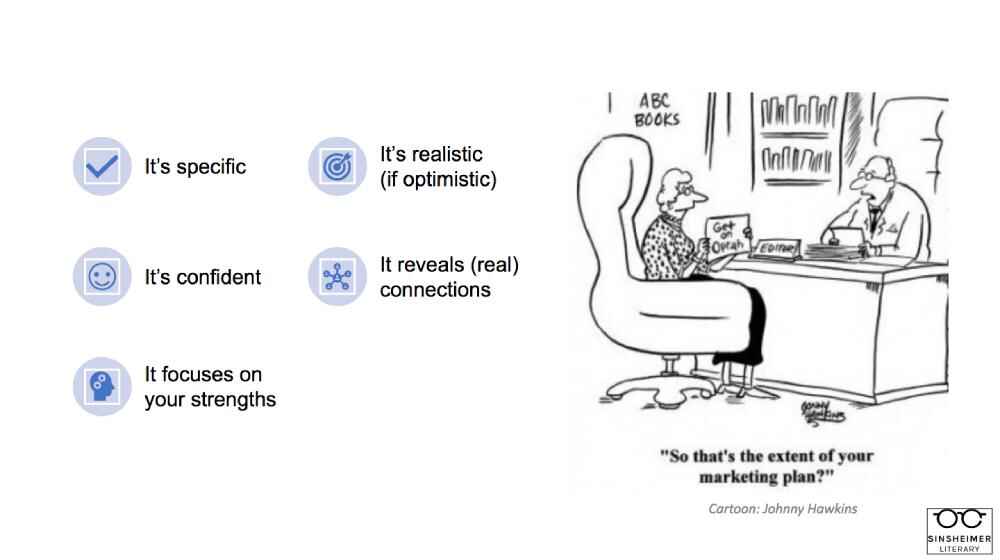

What makes a good marketing plan?

So let's say you can clearly show that readers will trust you and they'll trust you enough to spend a dozen or more hours reading what you have to say on the subject. The next step is to show that you can help the publisher actually reach those potential readers. That gets back to the idea of a platform. Jane Friedman talks about how an author's platform is the work of a lifetime, and my impression is that authors often don't realize how deep their connections run.

You need to do a brain dump. You need to think about who you know in the media. Or friends who work at institutions that host authors, people whose name recognition might be suitable for a blurb or even an early endorsement that could go in the proposal, as we talked about earlier. You need to do the same for your career — your past publications and speaking engagements.

You really need to think about your platform as a holistic thing, and no, not everything that you've done, or everyone, can or should be in a marketing plan. But do the brain dump, and you'll start to realize where you have elements of a platform that you didn't think of before. The flip side of the notion that an author's platform is the work of a lifetime is that it takes time to build. I often tell authors to come back to me, in six months to a year, two years after they've put kind of significant effort into building their platform.

Assuming you have access to readers, the key to a good promotional plan is convincing editors and their marketing and publicity colleagues that it isn't a Potemkin village. That your promises have substance. That your connections are durable. I think agents and editors have all been burned by authors that promise blurbs by Walter Isaacson and Reese Witherspoon and all the rest. Then they fall through. “Get on Oprah,” is, as the cartoon says, not a marketing plan.

So you want to be optimistic in how you frame your potential media coverage events, outreach to readers, but you don't want to be delusional. Don't overpromise, and definitely don't promise a bestseller. I assume the opposite every time I hear that. You also don't need to include every possible activity you've seen other authors do. I see this a lot where authors think if their book has some sort of industry or academic conference potential, they have to highlight how they plan to keynote a conference. Even though they've never spoken at a conference before.

A good marketing plan puts your best foot forward by highlighting the platform you already have. Not the one you wish you had. So focus on your strengths. And you don't have to cover everything. If you're not a public speaker, if the thought of going on a podcast absolutely terrifies you, you can highlight other things. You don't have to include it just because you see other authors do it.

Then again, more can be less with the marketing plan. I have seen so many authors recently just include 50 or 100 people who have agreed to read an advanced copy near publication to consider a blurb. I honestly weigh that near zero. It feels like a spray and bray strategy. Highlight real connections, not people you cold email who kicked the can down the road and said they “maybe” could look at a manuscript once you've written it. I don’t think that helps your marketing plan in the way that some authors clearly think like more is more. More is not always more.

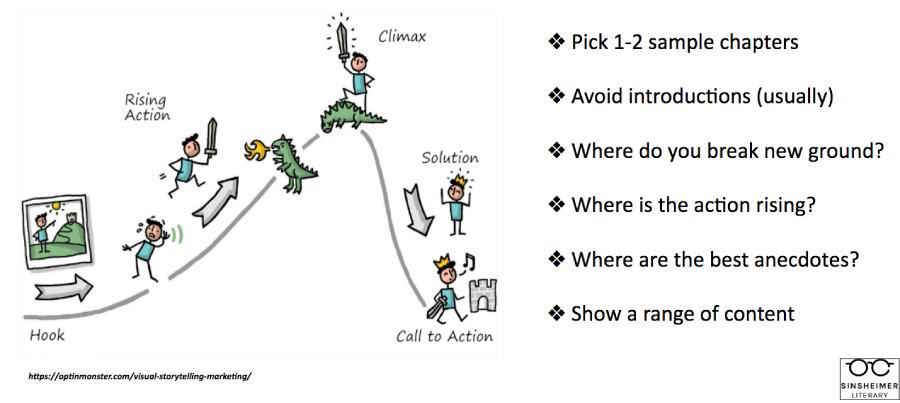

How to pick sample chapters

So we’ve talked about how in nonfiction you need one to two sample chapters — the exception is memoir where you really need a complete manuscript. As far as I know, and I've sold a couple memoirs, I've always been able to show editors the full manuscript. Different agents require different amounts of sample materials. Make sure to check their submission instructions. I suggest avoid picking your introduction in most cases. There's too much overlap. Often with the overview section of the book proposal, you want every part of the proposal, including the sample chapters, to feel fresh. I get a lot of submissions that are verbatim — a page or two from the chapter from the introduction is the overview section that starts their proposal.

And I don't want to be rereading material. It's a waste of time.

So what do you pick instead?

If it's a prescriptive or persuasive book I like to think about where you are breaking new ground — not a background chapter, or not the introduction. Pick a chapter that advances some original thought.

For the narrative — more narrative works like books of history, narrative journalistic style books, true crime, things like that — I think where the action is rising, where the pace is quickening. That rising action leg of the traditional storytelling arc that you see up on the screen. It can be really effective for drawing agents into the story. And just as it is for readers it's the part that gets your blood up, that's what you want in the proposal.

It's helpful to show a range of content types, if there's more than just text too. For example, I agented a book called Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake. It opens with a sake primer full with educational infographics about sake and then morphs into a sake travelogue. The authors go all around Japan, to all these multi-generational, 500 year old sake breweries and they meet the owners and the brewers. The authors in the proposal included some of those infographics from the Saki Primer chapter. Then they went to a really fun chapter from the travelogue. I thought that was great, and I certainly got a pretty good handle of what the book would be once I saw those two chapters.

Final thoughts

First, give your book a title. I get a lot of untitled submissions and I think even if you're deeply ambivalent about the title, I'm usually unimpressed by submissions that come in untitled. It just suggests that you're so overwhelmed by the querying process that you're afraid to misstep with the wrong title. Titles change. They change all the time. That's fine. A wrong title is better than no title. Give it a try. It's like the hook, don't abstain from that responsibility.

Next is, don't save your book ideas for your book. Authors are so afraid to cannibalize their ideas, to cannibalize their book by giving away the underlying research, or the underlying ideas before they sell the book to a publisher. In most cases getting the right readers to connect with you, to connect with those ideas through articles, op-eds, newsletters, et cetera — then expanding them into book form can only help you sell the book. It's like a proof of concept for the publisher.

With some exceptions, it is rarely a good idea to go into your cave, write your book and try to land a traditional book deal without ever having talked about any of the ideas that constitutes that book, in a public way. You're engaged in a public discourse. That’s what a nonfiction book is to some extent. I don't think it's a good idea to save it all for the book. I think you want to test those ideas out a little bit in the public sphere.

This is kind of a basic one, but I think in most cases a book trailer is completely unnecessary. If you do do it, do it much later in the book publication process. The same thing for the cover. A cover is absolutely necessary, but it's not your domain. It's the publisher's domain. And hopefully if you have a good publisher, they will consult you and you'll have some dialogue about it. But you look really eager, and sort of overstepping, if you send out a query with your cover mockup and a trailer. It actually hurts your chances. So inbox with confidence.

Even if you've been rejected by 50 agents and your last three books bombed, I don't need to know that. It's like dating: too much honesty closes doors. So, I know rejection — listen, agents deal with a lot of rejection too, trust me, authors. It's your baby so it feels even more painful but don't talk about the kind of sad story of your publishing life.

And then last thing is I think book publishing is one research project after another. Authors who take that seriously have a big advantage in querying agents. Obviously there are many nonfiction books which have a research component, and not just the ones you expect. I'm representing a memoir by a woman whose sister was one of the first Americans to receive a kidney transplant, and she, the author, did an extremely deep archival dive and original research on the history of transplants and donor lists. That research ended up really complimenting the personal elements of her memoir. I appreciate it. I learned a lot. I think people read memoir wanting to learn something. But even setting aside the manuscript, you have to know all of the podcasts and blogs and magazines and related books where your readers, your target audience, seeks information or entertainment relating to your topic.

So that's research. That's a giant marketing-publicity-audience-research project. Then finding the right agent is a research project. It never really stops. Every element, once the book comes out, unfortunately, publishers have sort of limited attention. You have a couple of months of their attention, hopefully. If you're so lucky as to get a traditional publishing deal, then there's a big burden of sustaining the energy and the momentum of your book. And so that involves all kinds of other research.

So be the expert, know your topic, but also like everything related to how you promote your book. It's a little neverending, but hopefully you're the type of person who likes research because that's what nonfiction publishing is.

Resources for querying

Just to round it out, here are a couple of resources for querying. The first two, Publishers Marketplace and Manuscript Wishlist, are helpful places to find agents. The next two are a couple of agent/editor blogs and newsletters with really good advice for querying. I read them both. Jane Freedman's Electric Speed and Anna Sproul Latimer's How to Glow in the Dark.

And then Reedsy, you know. If you can afford to hire a professional to review your proposal and query letter, Reedsy has some awesome agents and editors who can help you find your blind spots. My only advice is not to say you had professional help when you query agents. I get a lot of emails that say my proposal has been professionally reviewed and enthusiastically approved by Joe Bob. All that does is amp up the stakes for you because if I think it's a flawed proposal now, I can't really imagine how bad it was before. I think get that help, but get it quietly, is my advice.

Thank you all for listening.