This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. To find out how to work with Brooke on your next book, head to her profile on Reedsy.

So writing a picture book sounds like an easy thing to do. I'm sure that there are a lot of you who've heard the same thing I've heard, which is my husband saying to me, "Come on. How hard could it be? Just write a book."

Here's the thing: writing the book, yes, is easy enough. Writing a good book is a little bit different.

So I'm here to talk to you today about a couple of things that go into writing and more specifically planning your picture book. I'm going to cover: page count, paginating a book, and page turns; who your target audience is; illustrations; content — in particular, the use of language and rhyme — and then finally we'll end with what the top-selling themes are right now for picture books.

Page count

Before we get too deep in, let's talk about a couple of logistics for picture books. For those of you who are planning to publish through a traditional publisher, the biggest thing to know is the page count:

A picture book is 24 pages or 32 pages.

Occasionally, you will see one that is 40 or 48 pages. That's it; there is no wiggle room. The reason for that comes down to the way a book is printed. When the printer runs the paper through their presses, it gets folded and cut into what we call a signature which is 16 pages long, or a half-signature, which is eight pages long. You cannot print in anything other than that, which is why you cannot have a 34-page book.

For those of you who are planning to self-publish, you do have a little bit more wiggle room there because digital publishing works differently and you can print to whatever page count you want. But I would encourage you to stick to that 24 or 32 page count because that's what booksellers are expecting. It's what they're used to in the market.

Pagination

Now once you're looking at your page count and you start paginating your book, you want to keep a couple of things in mind. First, you are going to have space in your book for a title page and a copyright page, which eats into your page count. I say that now because I've seen a lot of books come through without that and then the book has to be reworked in order to fit those in. You want to make sure the world knows that you wrote the book and you own the book.

You also want to keep in mind when you're looking at your pagination where you want to put your page breaks. You want to give your reader a reason to turn the page, whether that's a logical turn of scene, whether it's the start of a new thought or the start of a new action sequence. You want to get to the end of the page and you want the kid who's reading the book to be dying to know what's going to happen next.

The other thing to keep in mind when you're looking at paginating your book is that a book starts on the right and it ends on the left. So that means that your spreads read from even to odd. They're pages 2-3, 4-5, 6-7, not pages 1-2, 3-4 and 5-6.

Again, I say that because you don't want to get too far into your book and find that you've planned a beautiful spread, only it doesn't work and you have to re-paginate the entire book. So knowing where to start makes sense.

Target Audience

So now let's talk about who the actual target audience is for your book. The target audience for a picture book is children ages three to seven. Seven is even hitting a little bit high. When you're talking about your picture books, you have to think about what kids are capable of at this age. When I was in first grade, I was learning my letters.

My three year old is learning letters now. He knows them. By the time he hits kindergarten, by the age of five, he's going to be reading by himself. So picture books are still going to be part of the bedtime process but he's going to start moving on to independent reading in the early chapter books and when he does that, he's not necessarily going to be interested in picture books anymore, so the six- and seven-year-olds are already really starting to age out of them, other than perhaps at bedtime.

I've had a lot of people say to me, "It's a picture book. It's up to ages 12." No, it's not. You're not going to see a 12 year old reading a picture book, especially a 12 year old... Because they're going to be embarrassed. They're going to be wanting to read a chapter book.

So to that, you need to think about what's compelling for a kid from the ages of three to seven. You need to think about their life experiences and what they can understand. A four year old isn't going to want to read a book about a 10-year-old because they're not going to understand the world they're living in. They might read about school, but it's not going to be a busy school day because that's not their world. They just don't get it yet.

There's a reason that most of the successful picture books that are out there are about young children, animals, and cars — they're things that kids can understand.

Keep their attention!

The other thing you want to keep in mind when you're thinking about the target audience is that little kids have wandering attention spans. For any of you who have read a book to a kid at night, especially when they're tired, it's hard to keep their attention. So you want to find a way when you're writing to get their attention and to keep it.

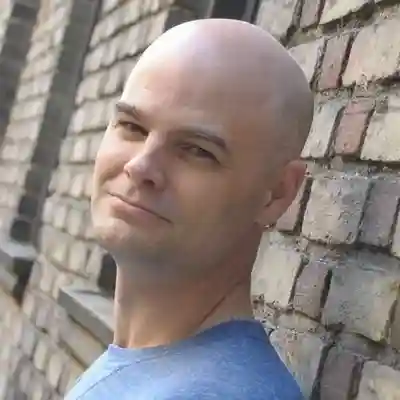

So this is a perfect example. This is Mo Willems' Don't Let The Pigeon Drive The Bus, and you can see right from the get-go, the audience is grabbed. The bus driver here invites the child into the book. They give them a reason to engage with it. It's their job to stop the pigeon from driving the bus. As you turn through the pages, you'll see that the kid is asked again and again, "Can I drive the bus?"

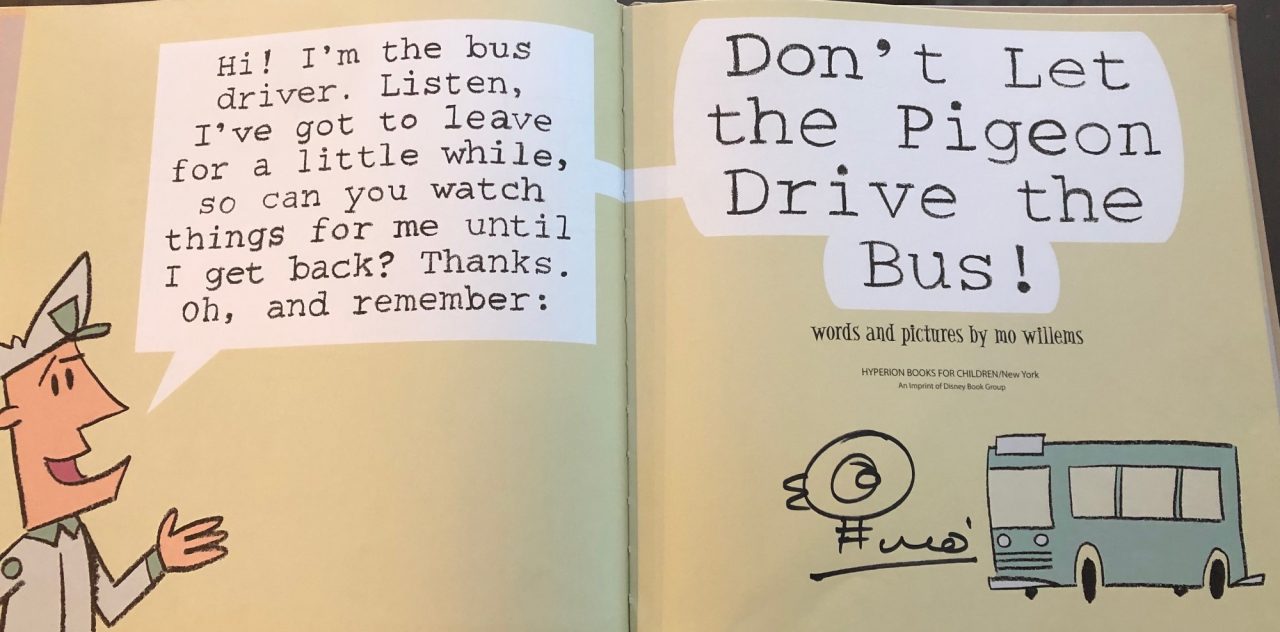

It's a great chance for the kid to shout out, "Yes!" Or "No!" Turn the page again, the pigeon again asks this question:

It keeps the child engaged, engaged, engaged, all the way throughout as opposed to losing interest as they move forward.

That being said, you also have to keep in mind your secondary audience for the picture book, which is of course going to be whoever is reading and buying. We as adults are the gatekeepers to what our kids are going to read.

Try your hardest to also get something in there that's also going to be appealing to the adults. I have to tell you, I've got plenty of books sitting in my basement right now. My son loves them, but I don't want to read them, so they get mysteriously hidden away. For me, if I don't like reading a book, it usually comes down to one of two things: either it's just not a very good story or it's too long, which brings me to to the next bit.

Can a picture book have more than 1,000 words?

A lot of you have probably heard of the thousand-word rule. For those of you who haven't, the rule is a picture book should not exceed a thousand words. So that raises the question: Is that a real rule? Is it okay for a picture book to go over a thousand words?

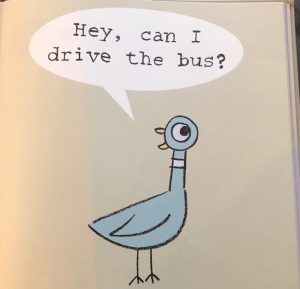

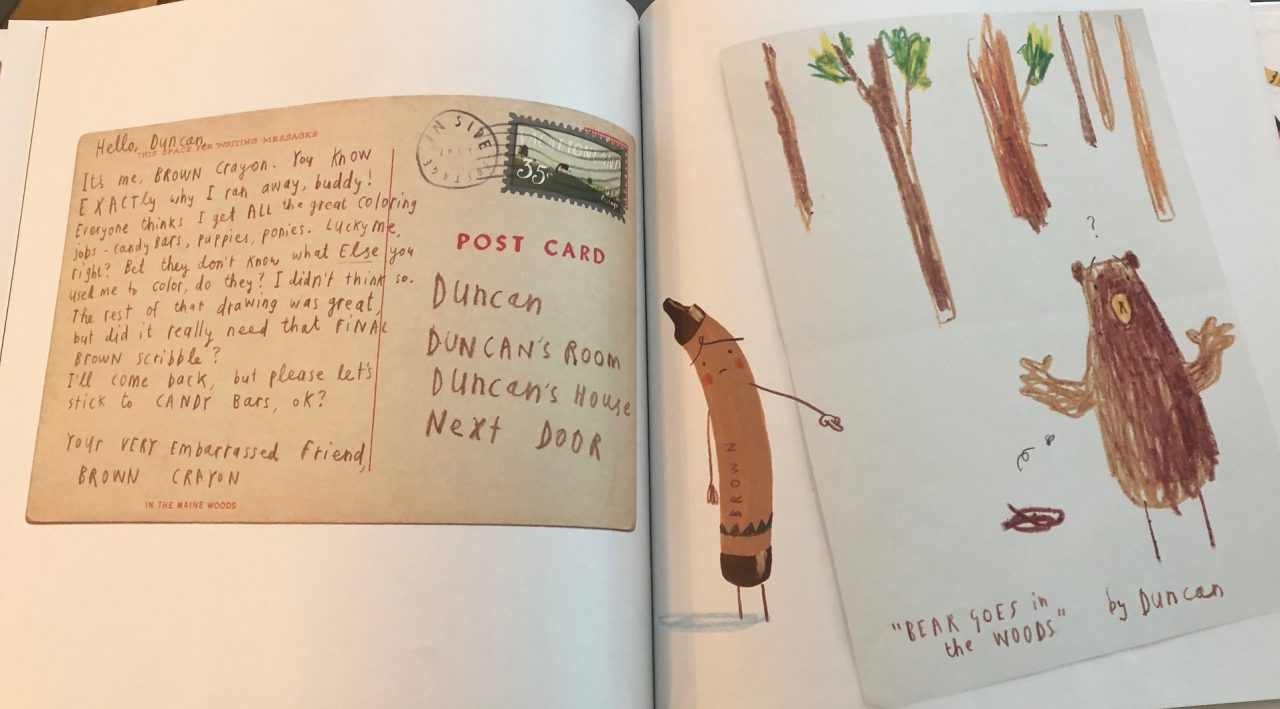

This book has a lot of text in it: 1200 words. And it was incredibly successful. So that answers the question. Does a book have to be less than a thousand words? No, it doesn't. What it does have to do is merit the length of the book. This one, for those of you who aren't familiar with it, is about a bunch of crayons who are angry with their owner and they decide to quit and they have written him letters explaining what their problems are. It merits the length because the kids want to keep turning the page to find out what the crayons' issue is.

So if you do have a long book, if you're looking at 1,200 words or 1,500 words or 2,000 words, which I've seen, go back. Think about whether all of your words are actually contributing or if you have an extraneous scene you don't really need. Are you saying something in 15 words that you could maybe say in five? And if you are, can you find a way to trim it to five because not only will that make it a faster read and keep the kid's attention, they'll probably understand it better. Take a look, see if there are scenes that you love that maybe you don't actually need.

Better yet, if you're too close to your book, have somebody else who hasn't read it take a look at it. Let them tell you if there's something that doesn't feel like it has to be there. Because the odds are that you may be holding on to a scene that's very close to your heart but doesn't actually further your story and it's just been there since the beginning.

If that's not what is going on, it's possible that the other thing that is keeping your book long is that you're using your text to describe your art. So that brings me to my next point.

Illustrations

The difference between the picture book and the longer book is that you don't need to use your text in a picture book to paint a picture of what you're seeing; that is what your art is there for. It will show us what's going on. It will set the scene for us so that you can take your words and you can make every one of them count to tell us the story. We don't need to know what we're going to see. If your character is wearing a green hat, I don't need to see that in my text.

That being said, if your character is chasing somebody who's wearing a green hat, tell me that. Because now that's a visual cue to my story. Now I can look at the page and find the character who's wearing the green hat. I can follow along with the action. It's the difference between just telling me what I can already see and giving me extra information. The art, inevitably, is going to show you what you've read. I understand that. That's part of it. But it should also further the story and give us information that is not in the text. They should complement each other. They should bring different things to the page.

Here's an example:

The letter on the left is from Brown Crayon. He's run away from home. He's angry because the boy drew something that embarrassed him. That is all that we're getting in the text. We haven't been given anything else. Now, if you look to the right at the art, you'll see that the name of this piece of art is "Bear Goes In The Woods", and the bear has obviously pooped in the woods which is great but we need the art to see that. Now our art is complementing our text and it's telling us what we're not getting out of our text.

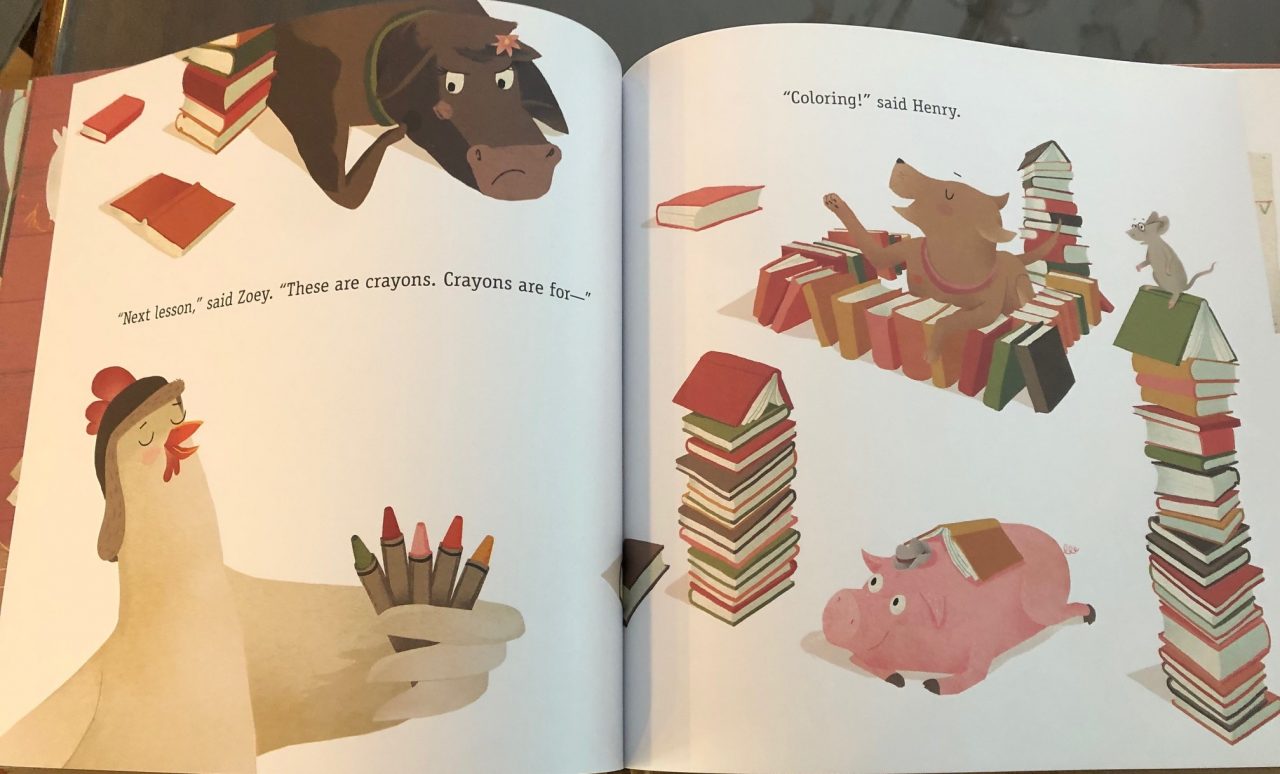

So here's another example where they complement:

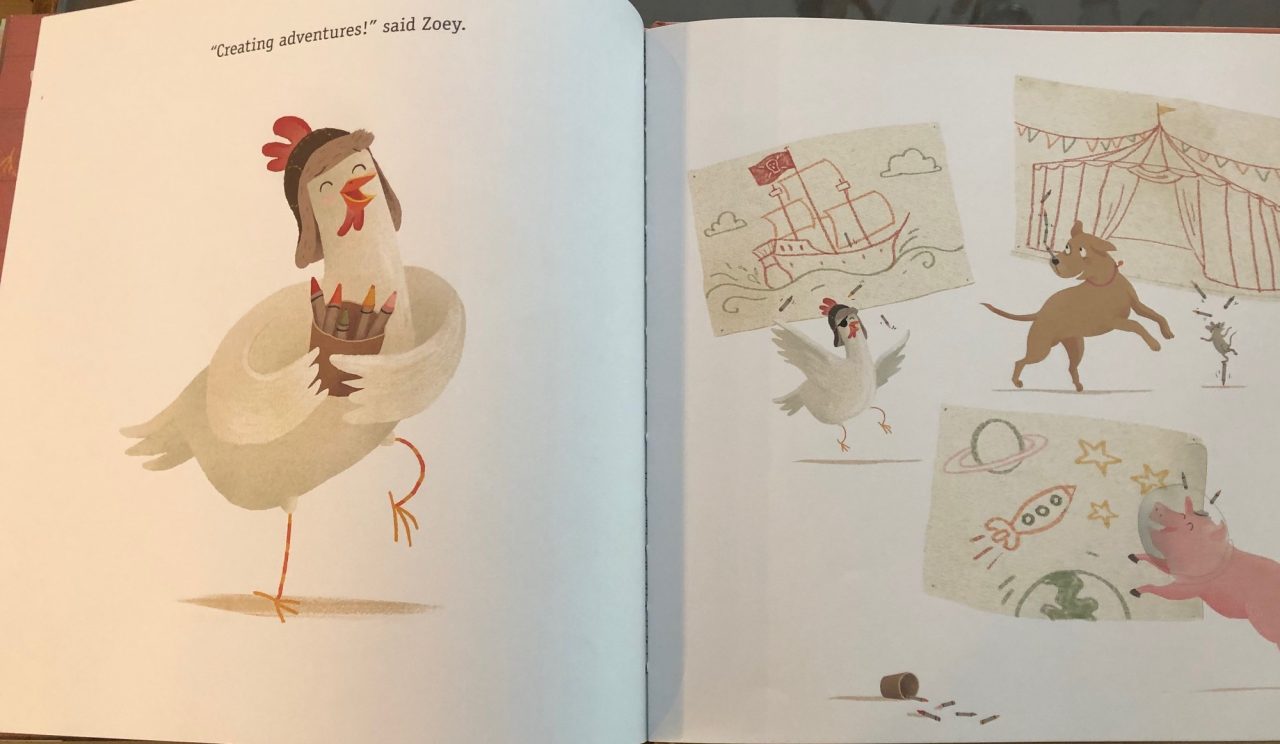

In this book, Chicken in School, this chicken is teaching the other animals on the farm all sorts of things. Here, she says, "What are crayons used for?" and one of the characters says, "They're used for drawing." Fine. That is a perfectly reasonable answer. But if you turn the page...

...you'll see that what she's actually saying is, "No, they're used for creating adventures." And again, that's all the text we're given, but looking at the art, we can see that the crayons have been used to draw amazing images of a pirate ship and outer space and the circus, and now the art is showing us the ways in which the imagination are built. So again, they complement each other. The text is slight; the art shows us something else. You want to keep that in mind.

Now here's the catch. If you're going out to a traditional publisher, your story needs to stand by itself without the art. Because a publisher is going to choose your artist, they're going to art direct, they're going to largely decide what is going to be on the page. Which is not to say that your opinion doesn't matter. It does, and that's where art notes come in.

You would want to include in your manuscript — especially if there's something that you feel is important to the story — an art note. On The Day The Crayons Came Home, that art note might have said, "The art shows a picture of a brown bear in the forest and he has gone to the bathroom in the forest." That note has to be there, because without it, the story doesn't make sense.

Same with Chicken at School: the art note probably said something to the effect of "there are creative, imaginative scenes that are shown with the crayons. They're doing X, Y, and Z." And that's how he's getting across what's not in his text. But art notes are great. You still want the agent and the editor who are reading this to be able to come up with their own vision of the story because that's what they're looking for when they're reading the book.

So if you are querying an agent or editor, unless you happen to be a very talented author and illustrator, I would strongly recommend you do not send your book in with illustrations. The art notes are great. It tells them what they need to know that's not in the text. The illustrations themselves really they don't work well because what happens is you end up putting your vision for the book into their head and you want them to be able to read it with enough vision that they want to pick this book up.

Illustrations with self-publishing

Now for those of you who are planning to self-publish, art is a different thing. You will need to create your own art notes. They will need to be very, very detailed and of course this is going to be your money going into the art notes. You're going to want it to look exactly like you want it to look.

However, I would encourage you not to start anything on art for your books until you have your manuscript locked. I have seen a lot of stories come to me with the art in place and I'm asked to do an edit on the book. At that point, it's really too late. You're locked into your story and there's no space for any changes to be made because the art is complete.

Wait before you start working on your art until you're content that your story is set and that beats are not going to change and that the page turns are not going to change, and you know what's going to be a single page and what's going to be a full spread of art. That's not to say that no words will change, but you'll end up with art that works for your book as opposed to trying to retrofit it to a changing story.

And if you are self-publishing, my other word of advice to you would be either find an artist who is a talented designer or find a designer to work with you in addition to your artist. You want to make sure that you're laying your book out properly. The last thing you want to do once you've spent the time of writing your book and once you've spent the time and your money on the illustrations is to find out that your illustrator left no space for your words to go. So now, speaking about words, let's move on to content and in particular, rhyming books.

To Rhyme or Not To Rhyme?

I have had a lot of people say to me recently, "I hear that publishers don't like rhyming books." I'm going to just put that to rest right now. There is nothing wrong with rhyming books. Rhyming books are published all the time. They do great. Honestly, the only issue with a rhyming book is that it's a challenge from an international sales perspective because the rhymes don't work when they're translated but if you're working with an agent and you have a good agent, that's going to be their problem and not the publisher's.

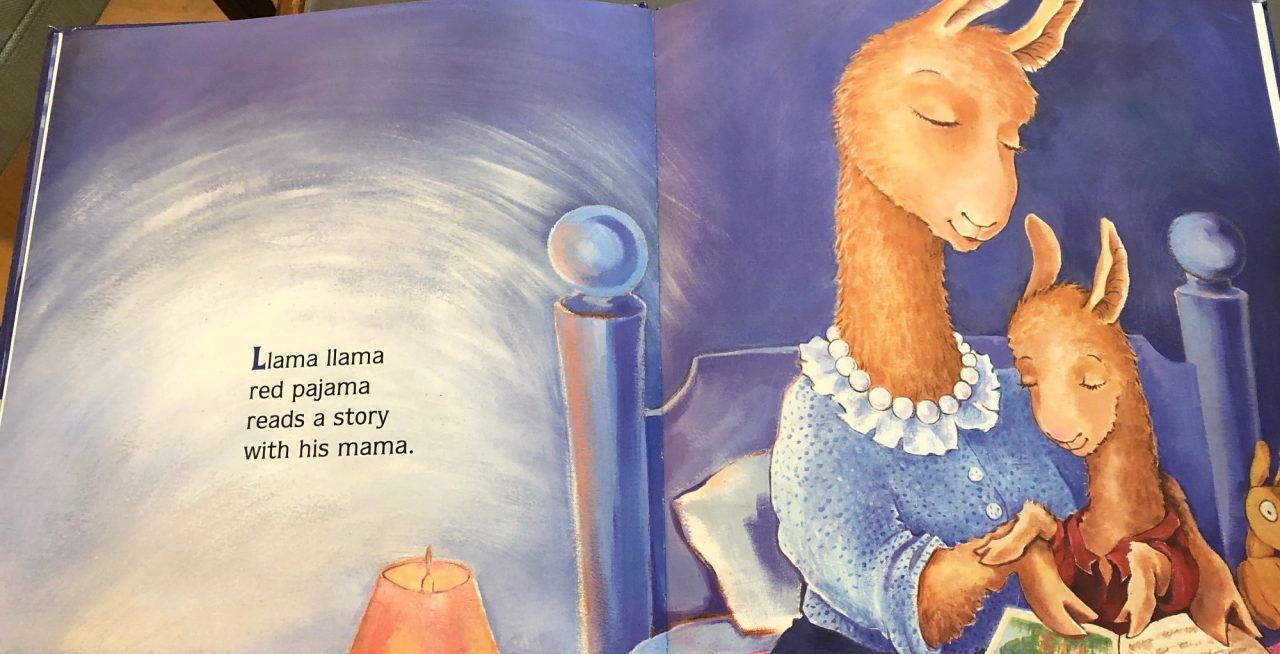

So, Llama Llama Red Pyjama. This was the first in a series of many very successful picture books. As you turn to the inside pages, you can see the text is rhyming and the text is very, very simple.

"Llama llama red pyjama reads a story with his mama." It's easy. It's simple. So again, there's no problem with rhyming books. What we don't want is bad rhyming books. Places where you have forced rhyme, places where the metre is off, places where you're using big words or the grammar is poor just to try to make the rhyme work. If you want to write a rhyming book, by all means go for it. But you need to make sure that the rhyme is working.

Try to read it out loud. See if you're stumbling over any of the places where metre feels off, because if you know your book inside and out and you're stumbling, a reader reading it for the first time is going to have a lot more trouble than you are. Or ask somebody who hasn't read it to read it out loud to you to see if it sounds good when it's somebody else reading.

Remember that rhymes work much better when your story is simple like this one is. This one is just about a llama who misses his mama when she goes downstairs. It's four lines of text per page, very young. The more complex your story gets, the harder you're going to find to get a rhyme scheme that works without using those big words.

Vocab

Now as far as big words, like I said before, remember that picture books are for very young kids so you need to use language that they can understand. The difference, obviously, between a picture book and a book the kid is reading by themselves is that they have somebody reading with them. They can ask questions and it's not a beginning reader who is trying to sound out the word on their own. Kids know a lot more words than we give them credit for and they have great vocabularies.

Books are a great way to introduce them to more words. It's okay to use bigger words in your book, but use them sparingly. You don't want to use so many that the kid has to ask over and over and over again what something means. The more questions they have to ask, the more they're going to interrupt the flow of the story. The more they interrupt the flow of the story, the more likely they are to lose interest in it.

What should you write about?

So finally, because we were talking about what interests kids before, I'm sure that each of you have your ideas for what you want to write. I just want to give you an idea of what's working in the marketplace and maybe it will help you, maybe it won't.

So across the board, the top-selling themes for picture books have been: bedtime, farm, ABC.

This makes sense because they're things that kids can relate to. Kids understand bedtime. They understand bedtime rituals: brushing their teeth, putting on their pyjamas, getting into bed, then reading a story. Their world makes sense when they're reading about that. Farm: the first things we teach kids are what a cow says, what a pig says, we sing "Old MacDonald" to them. Again, these are the things that they understand. They understand cars because they play with little car toys. They understand the concept of ABCs because we want them to learn to read, so we're using whatever we can to teach them their letters.

Also high on the list have been holidays, in particular Christmas, Easter, and Halloween. The reason for this is that they're marketable. If you walk into any store whether it's a Barnes & Noble, whether it's a Target, a Wal Mart, a grocery store, at the holidays you're going to see displays around those holidays and people want to buy gifts. Books are great gifts to give. There's a place for the booksellers to put them.

Now lately, there have been smaller holidays that have been on the rise: Mother's Day, Father's Day, and graduation are among the top ones right now. Again, they're promotional. Booksellers like them because they have a place to put them and they know they have an audience looking for them.

The good news about these is that they don't need to be a direct tie-in to the holiday. A Mother's Day book doesn't have to be about Mother's Day. It can be about a mother and a child. A graduation book doesn't have to be about graduation, and usually they're not. It can be something aspirational. It can give words of advice. Every year at graduation, the top selling book is Dr. Seuss's Oh The Places You'll Go (which also, by the way, rhymes).

Some of the other themes we've seen on the rise lately vary by where you're shopping, honestly. If you're looking to mass market stores like a Target or a Wal Mart, they've been very into mash-ups lately so rather than bedtime or farm, they want to see bedtime on the farm. The more traditional booksellers like Barnes & Noble are very into empowerment and calmness and mindfulness right now.

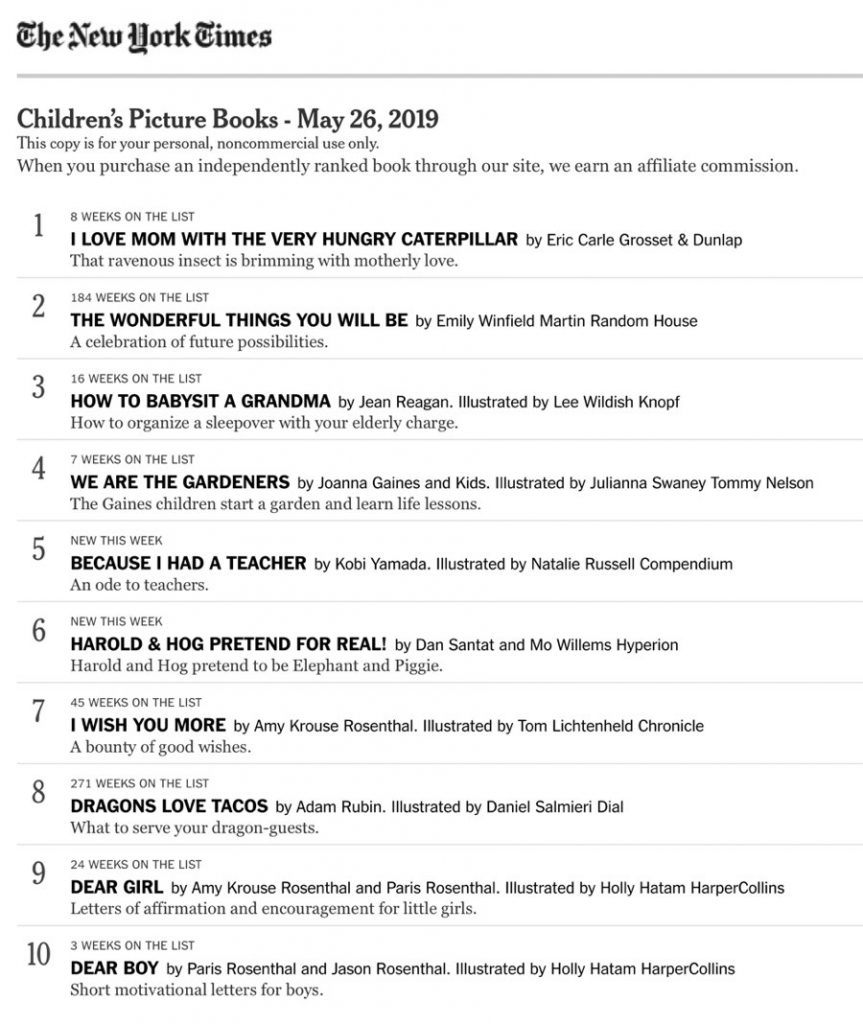

Right now, this is last week's New York Times bestseller list. Right at the top of the list, you have Mother's Day. You have graduation. Those are what are hitting right now, so this just goes to say these are the things that are selling well.

Now, these themes are a bit of a catch-22. The publishing houses know that these are going to sell well. They have slots to fill against these but they can't overfill them. Each house needs a graduation book, a Mother's Day book, a Father's Day book.

- I Love Mom with the Very Hungry Caterpillar — Mother's Day.

- The Wonderful Things You Will Be — Graduation.

- How to Babysit a Grandma — probably Mother's Day for grandma.

- We Are The Gardeners is just going to be a Spring-themed book or a Summer-themed book as the weather starts to turn.

- Because I Had A Teacher is probably a graduation book.

- I Wish You More is going to be a graduation book.

- Dragons Love Tacos just continues to sell well, and you're always going to see books that do well.

- Dear Boy and Dear Girl — letters of affirmation and encouragements for little girls. Again, those are going to be graduation buys.

So the publishers know this is going to sell while they're looking to fill it but they can only have so many. So if you are thinking about choosing one of these themes and working with it, remember that you're going to be competing not only for the one slot that they have but also against everything they've published in previous years. That's true of the other holiday books as well. It's a little bit easier to go out and say, "Well, I've got another bedtime book and I've got five bedtime books. That's okay." The holidays, it is more niche.

So my last word of advice if you do want to go to one of these, obviously there are a lot of these books so you need to find a new angle, something that hasn't been done before. Figure out what it is that makes your book special and focus on making that shine.

Note: For learn more, enroll in Reedsy's free course on publishing a picture book.

If you have any thoughts or questions on writing a picture book, drop us a message in the comments below.