Oksana is an editor on Reedsy, head to her profile to find out more and work with her on your book.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and includes writing exercises not covered in detail during the live webinar.

The first thing that I want to say is that reading is the best way to learn how compelling stories begin or just the craft of writing. But you can also do it by watching movies — storytelling is used heavily in scriptwriting playwriting. So don't feel like you only need to look at other writing, even though it is helpful. I come from a film background, so I always look at movies as a writer, which is a great way to learn.

Watch this fantastic webinar on starting stories from author/editor @oksanamarafioti

Click to tweet!

I hear people say, just write what you like, and everything will just work out. But that doesn't give credit enough credit to the craft of writing — because there is a structure. There is some sense of formula if you will.

Know the rules before you break them

And for those who are serious about writing, it behooves us to learn how to do it right. Even if we're not going to follow the rules — even if we want to break the rules, you still have to know them first.

What I'm going to talk about is just a general overview of how to start compelling stories. It’s based on an analysis of thousands of stories that have been done over decades. To see what works and what doesn't. Professional writers often have to write to a deadline and employ these rules because they know they work. But it doesn't mean that this is the only way to do it.

So you shouldn't take a writing class and assume that when a writing teacher talks about a certain way of doing something, this is the only way to do it.

Everything is structure

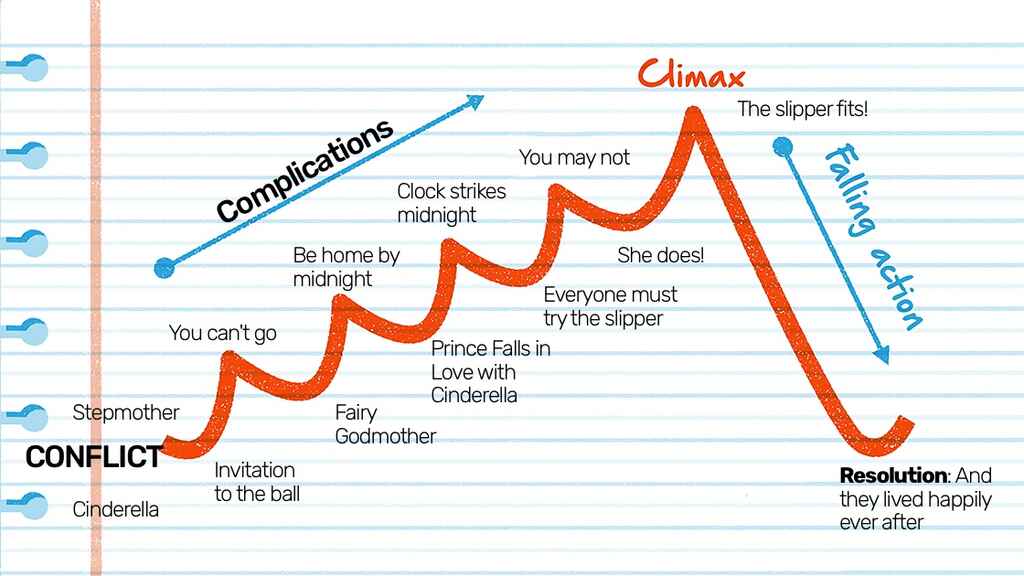

Storytelling follows a structure that comes to us from antiquity. Here is an example of a structure in a rising action in Cinderella.

This is just one example of thousands where a story starts with something that seems to be ordinary. Then suddenly, things change, and our main characters are thrown into an extraordinary situation.

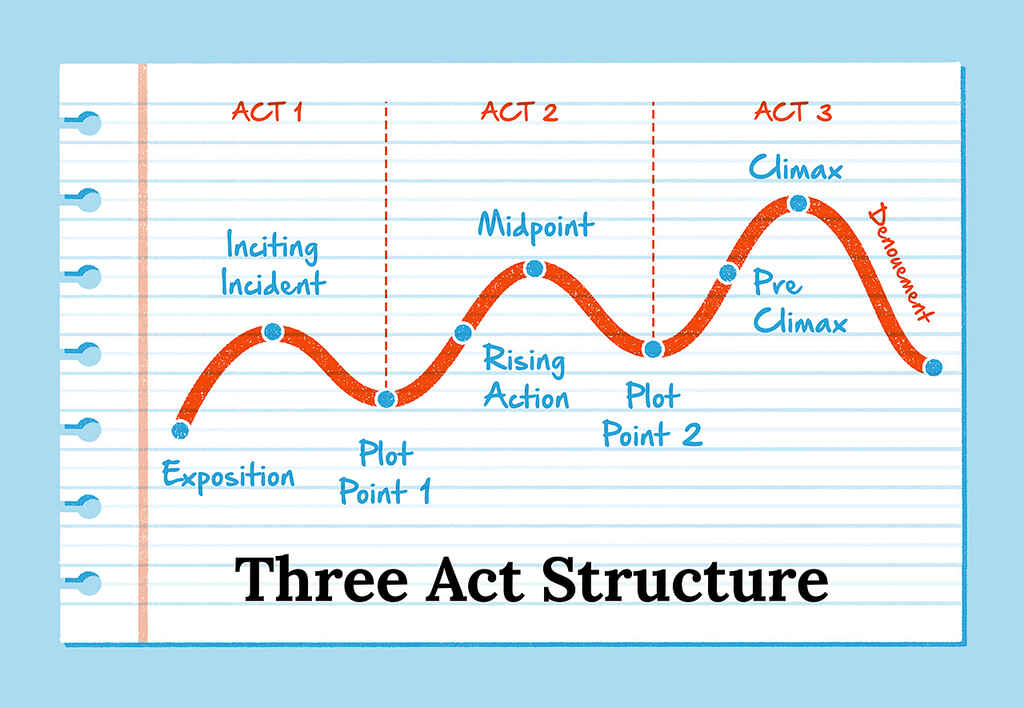

Here is another example of a three-act structure — something that filmmakers use as well as creative writers. Believe it or not, this also applies to non-fiction writers.

You have a setup in act one: certain things need to happen for our reader to be engaged enough. If you are writing for the public, this is especially important to remember. Our public expects certain things of us as writers. And if you don't quite believe me, think of yourself as a reader, what kinds of books do you put down? What kinds of do you love to read?

Act two relies on the results of the setup.

Act three is when we have our resolution. The central climax takes place near the very end of the story.

This is a pretty well-known structure, and you can apply it to a lot of different stories.

Free course: Mastering the 3-Act Structure

Learn the essential elements of story structure with this online course. Get started now.

This particular webinar will cover these four things:

- Where to open;

- How to open;

- What to put in your opening; and

- Where to close.

We are specifically talking about Act 1: probably the first 30 or 60 pages, depending on the length of your book.

What do we need to get the story started?

Before we go into the details of what I just mentioned above, we need to introduce a desire, a danger, and a decision.

- A character must want something;

- But they cannot get it very easily (the danger);

- So they must decide, “Do I want to go after this thing or sit it out?”

If the character chooses to sit it out, then we don't have a story. So by nature, we need characters who come in and say, “I want this enough.” And this is what jumpstarts the story.

The start is also where you also orient your audience. This is where you show your reader what kind of a book they're reading.

Establishing genre

This is a common question: how do you establish genre? From reading the first five pages, I should be able to tell what the genre is, based on these three elements: desire, danger, and decision.

Where to open

Editors often say, “start on the day that is different.” Think of every story you've ever loved: we don't have a character to whom nothing happens. Even if something doesn't happen to them externally, something is happening to them internally.

In Hollywood, a very, very common premise is “start with an arrival.” Now, I've binge-watched many shows, and I see so many series and films where it starts with somebody arriving in the new town, somebody arriving in a new job. Some might say that element is almost overplayed.

In Pulp — a genre that’s reemerging — they often say, “start with a fight.” Of course, we're not talking about not necessarily a literal fight. We're thinking about something really dramatic at the beginning of the book.

The element of change

So the element of change is trouble. A moment of change — the start of a story. Something will need to change at the beginning of our story to get a reader interested. The reader needs to know is that something may or may not work out for the character. They will keep reading the story to see whether the character makes it through their problem.

This change:

- Will be the trigger for a continuation of consequences throughout the entire book;

- Will set off a chain reaction;

- Will build conflict.

The character’s state of affairs must also be intolerant to them: they cannot attain or retain their desire at the start.

This is the same whether you’re writing a mystery or literary fiction: the main character is in such conflict that you, as a reader, must keep reading to figure out what's going on. In Pride and Prejudice, it might seem like nothing's happening at the start, but there are internal conflicts — an intolerable state of affairs for more than one character.

Formula for Conflict

Existing situation + affected character + consequences = desire + danger

I’m not saying that this formula means you have to do this just like this all the time — just be aware of this. So you have an existing situation.

As we open the book, we have:

- An existing situation that comes from before we met the character;

- We have an affected character — something happens to them;

- Then there are consequences to what happens after this change takes place.

- This equals a renewed desire to either face the change or step away from it.

- And then some kind of a danger to that.

The stronger the desire and the greater the danger to it, the stronger your beginning will be.

Now, this could apply to something simple:

We can have a young character who just changed schools because their family moved (existing situation). They didn’t want to move and leave all their friends behind (affected character) — and now they come into class on the first day, and they get bullied (consequences). All they want now is to fit in and prove they belong there (desire), but maybe the bully will stand in their way (danger).

The character will decide that they will go after the thing they desire — and this sets off a chain reaction of events that we’ll follow to the end of the story.

When should the change happen?

Well, your story can start right before a change, during the change, or just after it. If you read enough and you watch enough films, you'll be able to put a bunch of them into these categories.

- Start immediately before the change: maybe on the drive as the family's moving to a new town.

- Some stories start during the change: something extreme like somebody running away from a volcano.

- Or you could start a book directly after the change: Somebody is stranded on an island after a shipwreck, and the first scene sees them on this island by themselves.

Where you should start depends on your story. This is again where your creativity comes in. You might know the formula, but how you handle it is completely in your hands.

Knowing this information that we're going over today should give you the tools to change things. Instead of saying, “I don’t like how this starts — obviously, I can't write,” and just stopping, you can look back and say, “Okay, I probably didn't start in the right place. I need to go back and look at it again.”

Building the beginning around change

We have an existing situation. We have a change. We have a character, and we have consequences: what happens to the character mentally or physically as a result of this change?

Let’s put this into another scenario:

- Situation: A winter’s day

- Change: A gust of wind

- Character: A man who’s walking down a path in a park

- Consequence: He turns up his collar and hurries home.

Why does this not work? That’s because it’s too easy. Think about this and apply it to a story that you're writing. Is your challenge too easy for the character? Will the reader say, “well, I could easily just overcome that.” If that's the case, you need to rethink your beginning.

I'm sure that you've seen moments in stories where you thought, “why didn't they just do [this simple fix]?” It's kind of weird that they didn't realize that they could’ve easily avoided this problem.

Opening with change: potential problems

If you open too far ahead of the change, the reader might get bored. You might be revealing a lot of back story. Depending on the genre, a backstory might be required, but it's never actually required.

If you open during the change, the reader might lack the context to help them see what's going on. If that’s the case, you might need a little bit more setup.

And if you open too far after the change, you might have a lot of explaining to do.

Exercise #1: Use a story or film as an example of a situation/character/change/ consequences.

How to open

We're talking about, literally, the first paragraph. It's pretty well known amongst editors that the most critical parts of your book are the first and the last paragraphs — and in that order. In fact, I should be able to read the first and last paragraphs together and get a really good idea of what your story is about.

I have some examples here of various first paragraphs that work.

An effective opening will make readers want more information.

Example: The Secret History by Donna Tartt

“The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

It can introduce a theme

Example: A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

They often begin with striking character actions that set the stage for further developments

Example: Animal Farm by George Orwell

“Mr. Jones, of Manor Farm, had locked the hen-house for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes.”

It can set a fitting tone

Example: Harry Potter and the Philosopher/Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

“Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.”

So you have a narrator whose tone is very important, and your paragraph might serve the role of introducing that tone, that character, right.

It can play with the narrative timeframe

This is where you tell your reader that this will be the kind of book that will jump around in time a bit.

Example: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

Introduce the narrator’ voice

Example: The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

Exercise #2: Write an opening line or paragraph using one of the six methods listed above

By the way, these suggestions are not meant for you to look at as you write your first draft. When you write your first draft, I'm sure many of you have been told before to just let your creativity out and not think about anything related to editing.

First Lines

Here are some approaches to take with your very first line.

1. The unique

So, of course, you should start with unique lines. In your edit, it’s something worth working on for a very, very long time. If any of you are poets, you already know the value of a unique line — and if you're not a poet, you should be reading and writing poetry because poets are masters at words. They're wordsmiths.

So depending on the story, you should have something at the beginning that will make your reader say, “I need to keep reading here. There's something magical about this.

Examples:

- “I am an invisible man.” — Ralph Ellison, The Invisible Man

- “124 was spiteful.” — Toni Morrison, Beloved

- “Every summer Lin Kong returned to Goose Village to divorce his wife, Shuyu.” — Ha Jin, Waiting

- “It was the day my grandmother exploded.” — Iain Banks, The Crow Road

2. The unanticipated

You start with an anticipated. So perhaps the delicate heroine turns out to have multi-faceted insect dial eyes, or a hero proclaims himself a damned fool.

3. Deviation from the routine

Instead of getting off the elevator on her usual floor, perhaps Jenny rides two floors higher than walks back down. The reader's wondering, “Why? What's going on?”

4. Start with the change that is about to happen

Someone hears the hoofbeats of a galloping horse coming closer and closer down the road.

This is where you're tricking your reader — creating anticipation. Writing is often and very much about the psychology of emotion. We create a connection between the writer and the reader through emotions. That's pretty how it is with creative writing. Yes, there needs to be logic that comes with a story, but if you're not triggering emotions, the reader turns off, and they don't want to read anymore.

5. Inordinate attention to the commonplace

Another way to start is by paying attention to something commonplace.

Sometimes we do that unintentionally: describing a doorknob in tremendous, painstaking detail on the very first page. This will make your reader assume there's something important about it.

If you pay an unusual amount of attention to, say, a tree in the front yard or a little girl peering out from behind the dresser, you might say, “well, I'm just trying to create an ambiance.” However — your reader will immediately think, subconsciously, that something important is going on here. Why are we paying attention to this car part for a whole page?

It will be memorable and make your reader want to keep going because that image is fascinating for [what the readers assume is] a good reason.

Opening shots of movies do just that. That's often their purpose — it’s an image that hooks you into the rest of the movie. So writers can do the same.

Exercise #3: Write the first line of a story using one of the five methods listed above.

3. What to put in your opening

When we create a world, we start with a blank mind. The reader doesn't know anything about our story. They cannot tell where they are. They can not tell the genre. They don't know anything about the characters. They're going to ask three specific questions:

- Where am I?

- What's going on and

- Who am I?

Those three things need to be answered. And I know that sometimes, there are contradictions — and of course, there are many different ways of telling stories — but by page 30, if I don't know where I am, I will assume it's a mistake unless you make it very clear that this is intentional.

So, here’s how you might answer these questions.

Pinpoint only what is significant

So if you describe a girl or a boy or anyone within a certain way, it's going to stand out for your reader.

If somebody is acting clumsy in the very beginning, we're going to assume, as a reader, that this character is somewhat clumsy.

If you describe a girl as a “ditsy blond,” and you tag her far beyond appearance. In calling attention to that stereotype, you deem it a significant detail. Similarly, describing a character as “bull-necked” will give them a connotation that’s the opposite of sensitive.

Create significance by association

A little girl discovers a tiny demon monkey in her bed. Does she greet it with a warm smile and a hug? Or does she run shouting “not again”? Creating significance by association means how your characters react to things initially will dictate how your reader reacts to things in the book.

For example, if your story is set in a city floating through space: we open with a character walking through a hallway, look at the stars through the window — and they’re absolutely fine with it. So we, the reader, know that this is fine. But if the character wakes up, discovers that they’re in space, and go, “Oh my gosh, what’s going on?” — then we know that this is not normal.

So creating significant significance by association is a great way to build the world without back story.

Use symbolism (Freudian, dream interpretations, etc.)

If you have a storm brewing, it is almost always a metaphor for change — something is going to happen really soon. This is something that Shakespeare used often and well.

Exercise #4: Start a story in which character and setting are introduced in the opening line/paragraph.

“Where am I?” is a very important question for readers. They really want to know where they are, both in time and space, from the start. Of course, the exception is if you are intentionally and masterfully writing it ambiguously — otherwise, I’d want to know if I’m the 1500s or the 2000s pretty early on.

You can also add in a few significant details from the setting to set the scene.

So I hear this often: “When do I stop describing things? Because we're always told you need to be very descriptive in your writing.” You do not need to be very descriptive in your writing. You need to describe only things that serve the story. So in the very beginning, you should only show the things that are important to the mood you're setting and what kind of a story you're telling.

And again, this applies to non-fiction as well. I write creative non-fiction, and this still applies. What's going on literally means what is happening right now: we're starting this story right at this point.

What’s going on?

Establish the situation. What's the existing state of affairs, right? Show what happens in real-time.

What’s going on? means exactly that. The now. Not 'what's gone on' or 'past history/background'.

Show what happens. We can employ multiple senses. You don’t have to be nutty about it and write about all five senses in one paragraph. As writers of first drafts, we mostly employ the sense of sight and hearing — but in our rewrites, we can look to use the other senses. If we're, let's say, in a room where a lot of people are smoking, we're probably going to smell something too. So employing that smell, in the beginning, will help us set the scene and create a real opening. Our reader taps their emotions into the emotions of the character, and suddenly they're there.

Present conflict/opposition in real-time. We try to avoid backstory and explaining too much. This is one thing I see a lot as an editor: explanations about how the world works and why the characters are a certain way. The entire time I'm thinking, I just want to get to the story! So show me what's going on in real-time. Show me the conflict and all of that.

Establishing conflict without history

Now some people might ask, but how can you establish conflict without history? How can you have a fight without any background to it? Now you can, and trust me, the reader will be fine. We'll be just fine with that.

Okay. So how do we do that?

We write striking, self-explanatory scenes. Show events happening in real-time, show the characters interacting with their environment or other characters now, not in the past. The reason for that is that you can only truly experience a story in the present.

Whenever we go into a flashback, the reader switches the way they perceive the story — and it becomes passive. I'm not saying flashbacks are unnecessary. Sometimes they are right to have somebody remembering something. But we need to remember that where the reader connects clearly with the characters is in the present time.

Show what happens while it happens, in chronological order.

For example:

The paper clip lay on the desk between them. It was an old clip—discolored, somewhat bent, with a couple of small rust spots visible upon it.

Idly, Olivas reached for it.

In a soft voice, Sheenan said, "Touch it, you son of a bitch, and I'll cut your throat." Olivas' hand froze.'

Exercise #6: Use the text from exercise #4 to add a happening, a self-explanatory scene.

Who am I?

Who are the characters? The readers want to know.

Bring the character on “in character”. Think about what kind of a character you want to portray from the very beginning. What kind of a person are they? And again, look at other books, look at movies, look at shows. The first time you see them, you can tell exactly what kind of person they are. This will be expressed in their quirks, in things that they say and how they're behaving.

The first time they appear, they must perform an act that characterizes them.

Free course: Character Development

Create fascinating characters that your readers will love... or love to hate! Get started now.

Remember that book people are different from real people. Real people are multifaceted, and we're all over the place. You can be one person one day, a different person on a different day, and a completely different person on a third day. You change your mind about things all day long. But book people can not necessarily be so multi-faceted. So we usually choose the main characteristics that we want to portray in our character. Does this mean they will not change? Of course not. They need to change at some point.

Avoid telling us what to think of the character. The best way to persuade our readers is to describe the character’s reality. Then let the reader decide who these characters are. If you want to portray a villain, don't tell us they are a villain or a bad person. Show us something that they do. That is important — especially in the very, very beginning of a story.

As a test, those who have a manuscript go back to the first time you show your character on the page. What do they do? You will be able to tell what kind of a character you have on the page, right there from their action — even if you didn't mean to.

Exercise #7: Identify any or all of the following characters’ main traits.

Rumpelstiltskin • Braveheart (William Wallace) • Ebenezer Scrooge • Norman Bates • Morgan Freeman (as God) • Wednesday Addams • Sherlock Holmes • Inigo Montoya • Peter Pan • Alice

You can pick your own characters if you wish.

A bit more about beginnings

Or… Act One: Where Desire and Danger Gives You a Story Beginning

Again, remember that change comes in when our character desires something. Our character will then either face the change or run away from it. But whatever happens, there will be obstacles, and the first obstacle comes in at the very beginning.

So we open our story with curiosity-arousing devices that established two things:

- Your focal character has a goal, and

- This goal is threatened somehow

This is how you build suspense. Will they or will they not succeed?

They might not succeed at all in the end — and I'm sure we've read enough stories and seen enough movies where the character doesn't get what they want. In fact, the best stories are not about what the character getting what they want, but what they deserve. Or what they need.

But they do have a goal in the beginning — and from the very beginning, it is threatened.

4. How to Close Your Beginning

So, where does the beginning end? When this change comes in, how does it end?

The moment your focal character commits themselves by deciding to face 'danger', your actual story begins.

I always use this example: Let’s say I’m done with this webinar, and I try to get out of my office — but the door is locked. So that’s a change — because this door doesn’t normally have a lock on it. So I’m freaking out. What’s going on? Why is this door locked?

I move the handle and try to try and open it, but it doesn’t give. Well — I also happen to be afraid of small spaces, which adds to the problem. There’s no window, I can’t open the door, I’m screaming — this is an intolerable state of affairs.

Maybe the only way out is through a tiny door that leads to a basement that I know is haunted. I’m terrified of it, and I never go in there. But this is the only way out in this scenario.

Now, the moment I commit myself to face the danger is where the story starts: Am I going to go down this hatch into the basement to get out? Or am I going to stay in this room?

Now, the story is not going to start if I stay in this room — so you, as the writer, are going to push me to that door and make me face the one thing I’m afraid of. And once I open that hatch, stare into that black empty space and say, “I can’t believe I’m doing this” — that is the end of the beginning. This is where the story actually begins.

This decision must link to the story's very core and follow through to the very end. Everything else before that was a setup to show you what kind of a character I am — so that this decision can be linked to the very core of my story. If I go down the basement, hopefully, it's not going just to end there. Other things are going to start happening.

And this is where we hook a reader, and they have to see what's going to happen next. They have no choice. So this is all about giving a reader no other choice but to keep reading.

Exercise #8: Think of any examples of where a beginning ends from books or films.