Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

Kill Your Darlings: A Guide to Ruthless Editing

Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

View profile →The phrase “kill your darlings” means eliminating any part of your writing — characters, scenes, sentences, side plots — that, while you might love them, don’t serve your story. It’s often attributed to William Faulkner, though the earliest use comes from Arthur Quiller-Couch’s 1916 book, On the Art of Writing.

This can be a struggle for writers of all ages and experience. Who amongst us hasn’t grown overly attached to a beautiful turn of phrase, or an intricate scene we worked on for weeks? To help you find the best way to kill your darlings in the most humane way possible, let’s dive deeper into the meaning of the quote, and how you can apply its wisdom to your own writing process.

If something doesn’t serve your story, it has to go

Let’s take a look at Arthur Quiller-Couch’s original advice:

If you here require a practical rule of me, I will present you with this: “Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it — whole-heartedly — and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.”

First of all, notice how “kill your darlings” is an appropriately succinct variation on this long, somewhat dramatic quote. But also notice that Quiller-Couch doesn’t say avoid writing anything beautiful or extraneous at all costs. In fact, he encourages writers to give in to their impulses. Write it! Get all of those wonderful, ridiculous, and perhaps slightly unneeded ideas out of your system and onto the page. Don’t worry about whether it’s perfect. Being creative is already difficult, and it only gets harder if you’re constantly policing every sentence. Let your creativity run free and wild as you write your first draft.

Knives out in the editing phase

Once the initial excitement has faded and you’re looking at a completed rough draft, that’s when you can take out the red pen and decide who or what to snuff out. Killing your darlings is less writing advice so much as it is advice on revising. It reminds you not to get attached to something just because you love it, even if it’s the finest piece of prose in your manuscript. Instead, consider whether it actually belongs.

And if you’re having a hard time finding or editing out the parts of your story that don’t work yourself, an editor can help you make the tough calls on your manuscript and identify what needs to be cut or changed.

MEET EDITORS

Polish your book with expert help

Sign up, meet 1500+ experienced editors, and find your perfect match.

Imagine you’re writing a story about a hard-boiled noir detective with a mysterious past. He takes on a new case that bears a stunning similarity to his wife’s unsolved murder. You include scenes where he reminisces about his wife while working on the case, as well as conversations with witnesses, potential suspects, and his wife’s sister. One of these is not quite like the others, however.

The detective may have an emotionally-loaded argument with his late wife’s sister, where she blames him for her sibling’s death. But the detective has already expressed his guilt about his perceived hand in her death and has suitably complied with genre conventions by drinking extreme amounts of alcohol to cope while beating himself up about it. Rehashing those feelings with the sister could be redundant, even if it’s one of the best confrontations you’ve ever written. It’s not moving the plot forward (i.e., helping us find our killer), and it’s not teaching us anything new about our protagonist. You should always feel free to write the scene, but during editing, that interaction might find itself on the execution block.

With a finished first draft in hand, you can start ruthlessly murdering anything that doesn’t serve a purpose in your story. Now the question is what, exactly, are darlings? The term applies to anything that bogs down your story unnecessarily, but there are a few things that you can specifically watch out for.

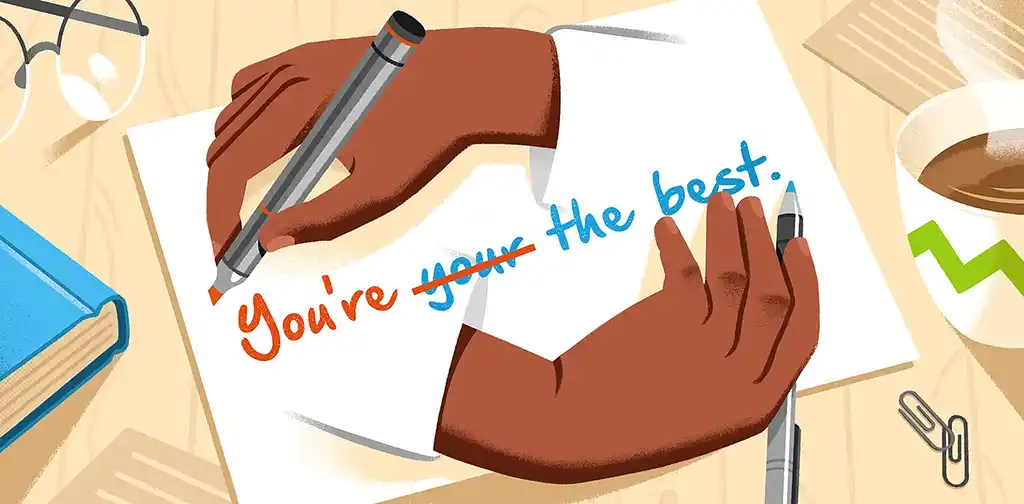

Watch out for purple prose

Clever turns of phrase and lush descriptions all have their time and place. Just be careful it doesn’t turn into flowery prose. This ornate and overwrought writing commonly disrupts the flow of the story. It looks good and sounds good, but its extravagance calls too much attention to itself. You want your readers to disappear into the world you’re creating, not be jarred by how it’s written.

That isn’t to say you have to write like Ernest Hemingway. Emotional and atmospheric prose can be useful when the moment calls for it. The line between beautiful and purple is subjective, and depends on the needs of the story, the wants of the author, and the feedback of editors and beta readers. If you have a poetic writing style or feel like it suits the purpose of a scene (or the whole story), you can leave it be. But if the way something is written is noticeably at odds with the rest of your style or distracts from the main point, consider rewriting it.

As an example, here’s a flowery passage that would give Hemingway a headache:

The sun traveled across the sky in an unerring arc, trembling with the stark inevitability of fate, burning the sparse grasses of the desert into the fine sands of time, sinking ever closer and closer to its daily mournful death. Beneath its uncaring regard, a man dressed entirely in the color of mourning made his dastardly escape across this barren land. Following in an endless, relentless pursuit, loaded down with steel, and darkness, and years of grief, was the gunslinger.

In theory, Stephen King could have written the opening to The Gunslinger like this, but it probably would’ve made even his biggest fans concerned. This paragraph is long and overbearing, taking a very long time to get to one simple point. Amongst all the descriptions, the real point is lost.

King actually started his story quite simply:

The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.

Short, punchy, and mysterious, this sentence is an enticing opening. The reader has many questions about who the man is, why he’s being chased, and the overall setting of the story. While the earlier paragraph might answer some of these questions, it has no intrigue. This short introduction instead immediately brings questions to the mind of the reader — questions they’re going to have to keep reading to answer.

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Book Editing Checklist

Resolve every error, from plot holes to misplaced punctuation.

It’s not just the micro-level darlings that have to face the firing squad, either. Your scenes and chapters can pose problems as well.

Make sure each scene pushes your story forward

On a more global scale, pay attention to what entire scenes and chapters add to your work. You might be fond of a scene where your characters indulge in a monologue on your favorite topic, or a chapter that deeply explores the background of your most beloved side character. But do they muddle the story and prevent it from moving forward? If you take it out and it changes nothing about the overall progression, you might be dealing with a darling.

For example, romance novels rely on interactions between the main character and their love interest to increase the tension and drive the story — as well as their relationship — forward. Say you’re writing a Regency novel about two bachelors who are competing for the affection of a duchess, only to fall in love with each other along the way.

Perhaps your research has given you a new appreciation for British men’s fashions of the early 19th century, so you include a detailed chapter where your hero, the Viscount, visits his tailor and makes decisions about his new wardrobe. While this may be interesting and could reveal something about his character, ultimately, it might not tell the reader much about the relationship between the two men or the plot.

This doesn’t mean throwing out sections that are slow or go slightly off the beaten path. What you’re looking for are the parts that don’t fit your story at all or serve your main point, especially those sections that you might be a little too attached to. The same thing can happen with characters.

Cut or combine unnecessary tertiary characters

Perhaps the most literal darlings are your characters. In writing them, you’ve gotten to know them so well they might as well be friends. It can be painful to even consider getting rid of them. But you only have so much room on the page, and the more characters you have, the more difficult it can become to keep track of them — for you and your readers. This doesn’t apply to your main characters so much as the supporting cast.

It’s very common for this to happen in adaptations of books and fictionalized accounts of real-world events. The HBO miniseries Chernobyl, which chronicles the 1986 nuclear disaster, does this with one of its characters. Writer Craig Mazin needed a way to represent the many scientists who investigated the disaster — but he didn’t want to overload the audience with too many characters. So instead of portraying each individual scientist, he created a composite character, nuclear physicist Ulana Khomyuk, to serve as a stand-in for the many real people who worked on containing the incident.

Often, the roles played by two or three characters can actually be filled by one. Even if you really love the wacky neighbor and the main character’s comic relief best friend, if they serve a similar purpose, you can streamline your narrative by discarding one of them. Or you can combine them to create one character who plays multiple roles (a wacky best friend who lives next door!).

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

If you’re feeling squeamish about all the brutal killing, don’t worry. There are less violent ways to kill your darlings.

Don’t kill them, find them a new home

Erasing something you put a lot of effort and emotion into is tough. The good news is you don’t have to! Treat it like an animal rescue instead.

Rather than outright deleting them, make a separate document to transfer any darlings you find and keep them around for a rainy day. There’s obviously something you loved about that character or chapter. They can serve as inspiration for other projects and might even be useful later on in the same story. Just as a deleted scene can lead to a new book idea, a character cut from one project can be the star of another.

The main character in Rainbow Rowell’s book, Carry On, was actually a fictional character in the universe of her earlier novel, Fangirl. Although Simon Snow is present in the fanfiction the main character of Fangirl is writing, Rowell doesn’t bring him to the foreground or use his story to parallel the main narrative. Instead, she channeled her love and curiosity for him into a spinoff series where she gets to explore everything she couldn’t in Fangirl. Simon’s second life proves that a beloved darling doesn’t have to go the way of the dodo — and can rise like a phoenix for a story entirely of their own.

Authors across genres and periods have extolled the virtues of killing one’s darlings. Though a critical editing eye is an important quality writers should cultivate, don’t let it keep you from fostering darlings in the first place. Have fun as you write, but keep a sharp implement handy during your editing process — and don’t be afraid to use it.