Last updated on Aug 21, 2023

How to Start a Children’s Book: Coming Up with Your Big Idea

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →The hardest part of writing a book is often starting it. Even in the world of children’s books, where many assume the process to be simpler, finding your first idea and turning it into a fully-fledged story can be daunting.

In this post, we look at what it takes to build up your idea before you start writing your book for children. To help you along the way, we’ve included advice from experienced children’s editors, including Colleen Kosinski, Elissa Weissman, Salima Alikhan, and Leila Boukarim.

1. Pinpoint why you’re writing a book

The first question you should ask yourself is a big one: why do you want to write a book? There are endless numbers of reasons and everyone is going to have a different answer. You have to find what resonates with you the most and that will sustain you through a long, and occasionally difficult, creative process.

Are you doing this for yourself? For money? For fun? For your kids? For something else entirely? There’s no right or wrong answer here. Dr. Seuss famously wrote The Lorax because he was angry about how the logging industry was destroying the environment and wanted to create a story that was more engaging than the ecology textbooks he’d been reading on the issue.

Dig into what’s driving you to write and create and put that at the forefront of your mind as you ideate and eventually start writing. A clear purpose will give you clarity and something to go back to if you hit a slump in your writing or publishing journey. Once you understand why you’re writing, it’s time to think about who you’re writing for.

FREE COURSE

Children’s Books 101

Learn the ABCs of children’s books, from audience to character and beyond.

2. Identify your target reader

Children’s books are divided into strict categories by age and word count. Depending on who your ideal audience are, your entire approach can change, so you’ll want to know what audience you’re aiming for before you start writing. Your reader’s age will affect:

- how you approach your story’s topic,

- the language you use,

- and even how long your book will be.

While you might want to aim for being universal and include as many different readers as possible, that’s a difficult task to accomplish. Unlike in most other parts of publishing, the age range of your readers can’t be too broad. As children’s book editor Elissa Weissman says, “Children grow and develop quickly, so keep your target age range tight. There aren't many books that will appeal to both a six-year old and a twelve-year old, and that's okay.”

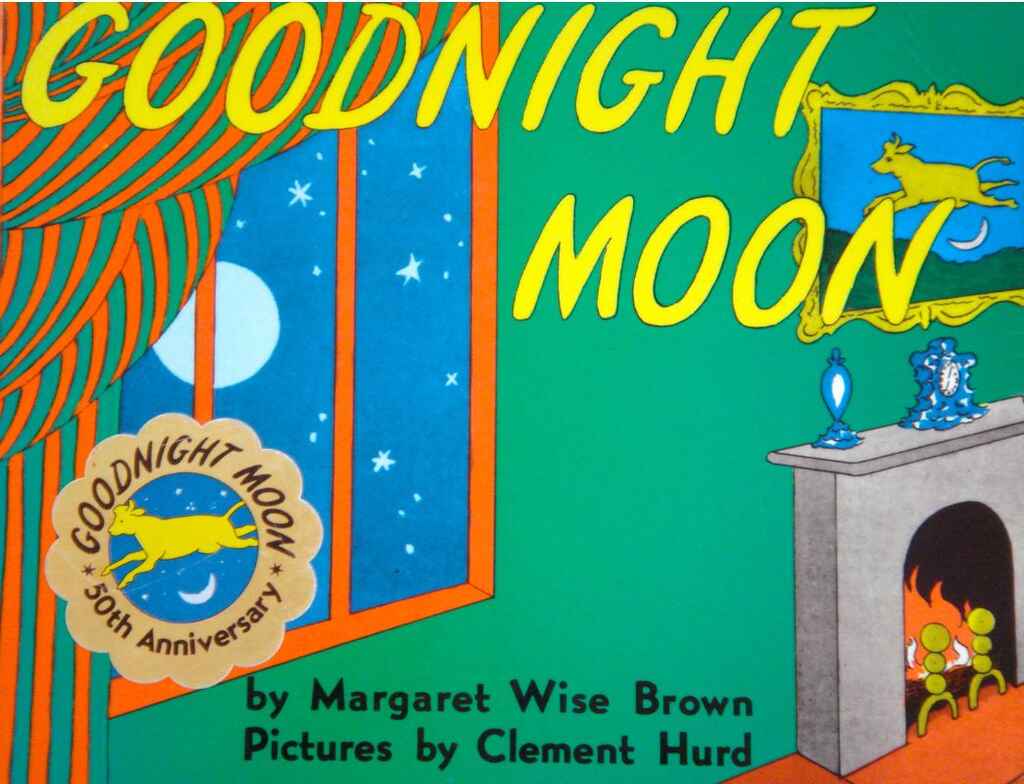

A simple picture book like Margaret Wise’s Goodnight Moon isn’t likely to be interesting to a ten-year old much like The Magic Tree House books probably won’t hold the attention of a younger reader.

Protagonists are a year or two older than your readers

Another thing to consider, according to Weissman, is the age of your protagonist in relation to your reader. “In general, kids like to read about characters who are their age or a year or two older. If your protagonist is eleven, for instance, your readers will most likely be nine or ten.”

To give you an idea of how publishing separates age ranges, here’s a handy list:

- Board books:

- Ages: 0-3

- Word count: 300

- Picture books:

- Ages: 4-6

- Word count: 400-600

- Early readers:

- Ages: 6-8

- Word count: 2000

Finally, as you construct your ideal reader, remember that gender isn’t quite as important as you would think. Age can be a good indicator of what someone will find interesting, but gender isn’t quite so clear cut. “There's no such thing as ‘girl books’ and ‘boy books’!” says Weissman. “Don't assume or suggest that your readers will be of one gender or another, no matter the gender of your protagonist or the content of your story.”

With a target audience in mind, it’s time to start exploring your genre and niche in depth.

3. Read and research popular books in your niche

You have some general ideas floating around in your head and you know who your audience is. Now it’s time to have a little fun and explore the wonderful, whimsical world of children’s books, while still being able to call it research.

Take a trip to your local bookstore

You want to get an understanding of what’s popular and what people are reading. After writing over 20 books for people of all ages, author and editor Salima Alikhan has a few suggestions for how you can do that.

“Read, read, read as many current books in your chosen genre as possible! An easy way to do this is to visit your local bookstore and see the new releases on the shelves. Many stores, especially indies, have bookseller recommendations on the shelves as well.

“Talking to the booksellers is always a great idea, too — ask them what kids are asking for and interested in right now.”

Bookstores let you see quickly and easily what’s being published right now and how it’s being marketed. It gives you an up-to-date look at the market so you can begin imagining how your own book might fit into it.

Along with the expert knowledge of booksellers, don’t forget to head to your local library to peruse the shelves and speak with a librarian. They’ll have knowledge not just about current trends, but what’s been popular in the past and what’s never gone out of style.

… or hit up the internet

Take a look at what’s available on Amazon as well and what comes up on its bestseller lists. Check out the bookish communities on social media as well and pay attention to what's being talked about and hyped the most across platforms, both through word of mouth and influencer channels. This will give you an even broader look at what’s popular across the internet and also what people like so much about these books.

Now you have an idea of what’s already out there and where there might be any gaps. Consider how your story will fit into this landscape and how you might be able to market it, along with any comp titles you may have discovered.

4. Draw up a list of things that matter to your reader

After your initial research stage is over, it’s time to really dig into your ideas. Spend some time thinking about what matters to your readers and what they might be interested in. See where your inspiration might lead you.

Be on the lookout for ideas

Don’t feel like you have to stick to a certain topic or subject matter. Author and editor Leila Boukarim believes that ideas can come from anywhere and anything. “Ideas are everywhere, and the best thing we can do as children's authors is train ourselves to see them.

“We are surrounded by stories, so always carry a notepad and pen to be sure you jot down anything that comes to you, whether it feels important or not. One word, one image, one smell might, one memory can open a door to a story you didn’t even know you had in you.”

Find what’s important to your readers

Create a list so you can keep track of everything and pinpoint any places where your ideas intersect. Consider thinking about your ideas with these three categories in mind:

- things your readers enjoy,

- things your readers fear or are affected by, and

- major life milestones.

Things your readers enjoy are fairly simple. Dinosaurs? Princesses? Cats? Dogs? Fairies? The ocean? This might be anything that children are fascinated by and would want to spend a lot of time learning and/or reading about.

The things that they fear or are affected by are a little more complex, encompassing real-world problems and emotions children may encounter in their lives. This could be everything from monsters to self-esteem to dealing with complicated feelings.

Finally, don’t forget to think about major life milestones. These are the big things that a child might go through, any changes or shifts that happen in their life that completely change the status quo. For example, starting school, moving to a new home, or getting a sibling are just a few milestones children will be concerned with.

Bring all your ideas together

Often, you can combine things children enjoy with the bigger problems they face to tell a story in a way that is relatable and makes a difficult subject easily understandable to them. If a child likes dinosaurs, a story about a T. Rex on their first day at school will not only be a source of entertainment but a way for them to process their own feelings through a character they like and relate with.

You might wonder if your idea would even work for children. Boukarim advises to not worry about that, especially in the ideation stage. “There are children’s books about teddy bears, children’s books about genocide, and everything in between. Just write it down, and work on the execution as you revise, with your target audience in mind.”

With some ideas in mind, it’s time to put them to the test.

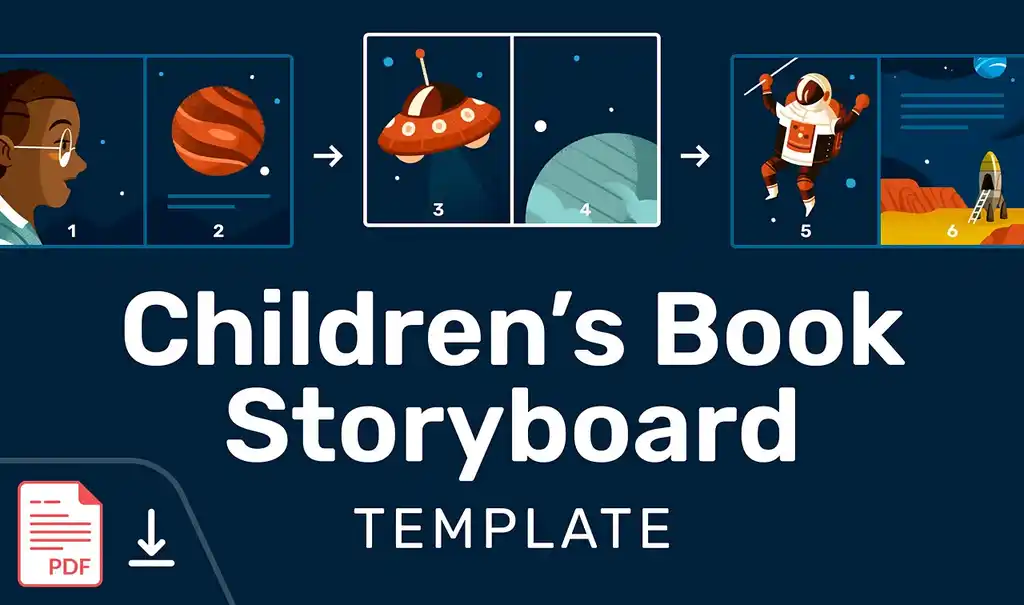

5. Write a two-sentence summary of your story

Whatever idea you have, it should ideally be simple. A children’s book, no matter the age range, should be fairly easy to understand, without too many complicated twists and turns. One way to test this is by writing a two-sentence summary of your story. If it can’t be summarized in two sentences, it may be too complex.

By thinking about your summary in advance, you’ll be able to see whether your idea and your character mesh well together. Does the story you have in mind make sense for the character you created? Are they working in tandem to further your message?

To give you an idea of what this would look like, let’s look at two examples from classic children’s books.

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

A young boy named Max wreaks havoc in his household and is sent to bed without his supper. When he goes to his room, he is transported to another world full of wild beasts, where he becomes their king for a time, before eventually returning home.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury

Five siblings cross various terrains while hunting a bear, and eventually find one in a cave. The bear chases them back home, where the children hide from the bear until he goes away, and vow to never go bear hunting again.

We can break these examples down into a story formula that looks like this:

A [protagonist/protagonists] experiences an inciting incident which leads to repercussions of this moment [End Act 1].

Max wreaks havoc and is sent to bed.

The five siblings go bear hunting and eventually find one.

After this their greatest fear comes true and they must overcome obstacles to conquer the goal; OR their dream comes true, but soon turns to trouble when they realize what they wanted wasn’t what they needed [End Act 2].

Max is transported to another world full of monsters and wild beasts, and is soon crowned their king.

The siblings find their bear but instead of it being an adventure, it becomes a nightmare. They’re chased all the way home and must hide until it goes away.

With the climax of Act 2, our protagonist/protagonists learn their lesson and return to their lives changed.

Max experiences parenting via ruling the wild beasts and understands his parents frustrations, returning home wiser.

Having hid until the bear disappeared and learned the lesson of their misadventure, the five siblings vow never to go bear hunting again.

This is also a great way for you to practice turning your ideas into mini stories. By writing out ideas like this you’ll also see where you might need to find more inspiration, or come up with a new turning point for your book!

6. Start drafting

You’ve done all your planning, but how do you know when you’re ready to start writing? Author, illustrator, and editor Colleen Kosinski finds that as much as you need to have done your research, there’s something more important that you need to know in order to write. “Your idea needs to be a story — not just an idea. A story has a beginning, middle, and end.” So once you know your target audience, what your readers want, and above all, the story you want to tell, you can finally jump in and start drafting. The writing process is an entirely different beast from the initial planning stages, so if you want some advice on how to go about creating your first draft, look no further than our guide on how to write a children’s book.