Posted on Apr 11, 2025

How to Plot a Novel: 4 Ways to Get from Idea to Story

Loretta Bushell

Loretta is a writer at Reedsy who covers all things craft and publishing. A German-to-English translator, she specializes in content about literary translation and making a living as a freelancer.

View profile →You don’t have to plot your novel before you start writing — just like you don’t have to get breakdown cover for your vehicle. But you’ll regret your decision if a massive p(l)ot hole derails your journey halfway in!

Plotting helps you avoid inconsistencies and tangents, gives you a sense of direction, and saves you having to completely rewrite your first draft.

Outlining has similar benefits, but plotting and outlining are not the same. Outlining is putting your story into the order in which you’re going to tell it (which is not necessarily the order in which things occur). Plotting is coming up with the story to outline and must happen first.

There’s no right or wrong way to develop your storyline, but if you need inspiration, here are four ideas for how to plot your novel.

1. Apply the holistic Snowflake Method

🌟 Best for: writers who have a vague idea of the entire story.

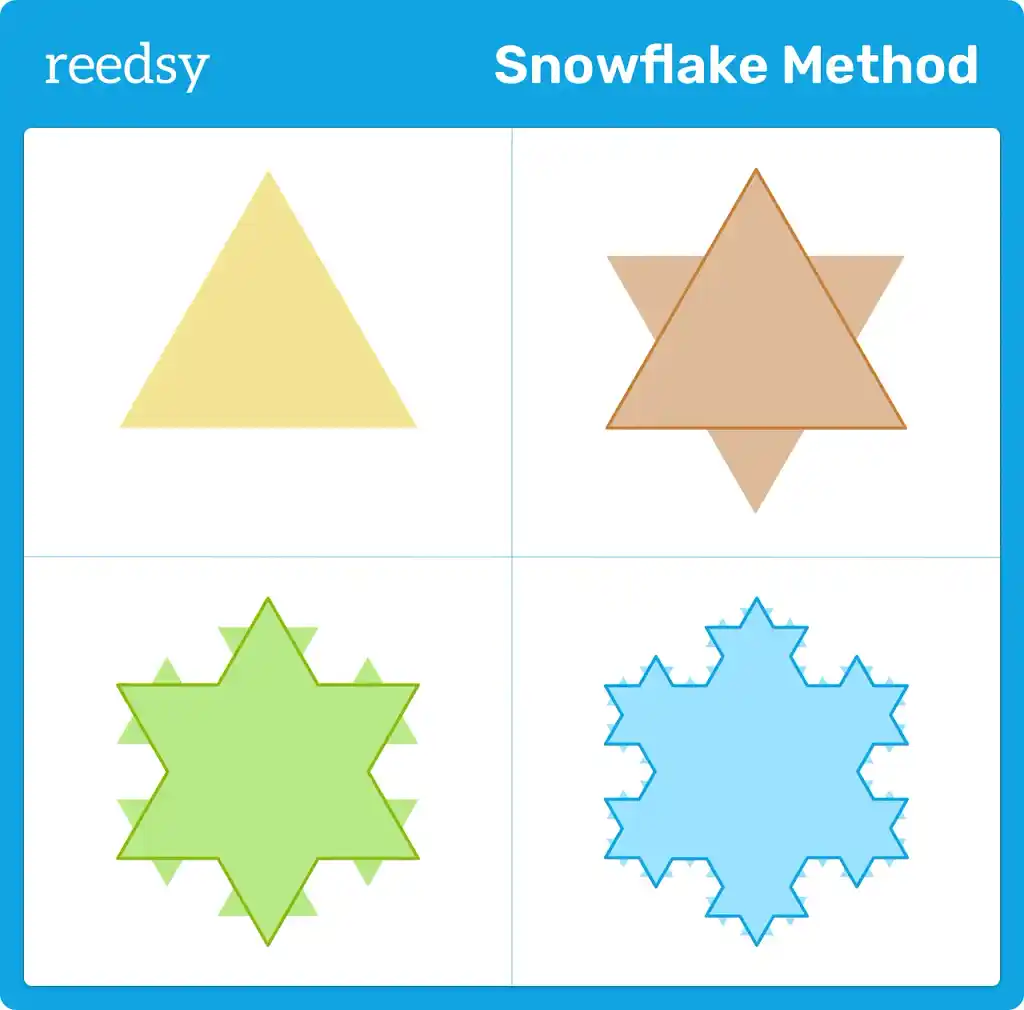

Created by American author, physicist, and writing coach Randy Ingermanson, this approach to story development was inspired by the Koch snowflake. You can draw this shape by starting with a triangle and repeatedly adding more sides until the end of time — or until you get bored.

In the same way, the Snowflake Method lets you start with a single sentence and keep expanding on it bit by bit until you have a comprehensive plot summary.

Ingermanson’s original Snowflake Method has ten steps, but we’ve condensed it into six:

-

Write a one-sentence summary.

No cheating by using lots of semicolons and relative clauses! Ingermanson advises that you limit yourself to 15 words. Focus only on the central idea of the novel — specific details like character names can wait.

-

Expand it into a one-paragraph summary.

Again, don’t be too liberal with your definition of a paragraph. You only need 5 sentences: one to set the scene, three to summarize the most important plot points, and one to wrap the story up.

-

Work out each major character’s arc.

Spend about an hour coming up with their name, role, motivations, goal(s), conflict(s), and how they change over the course of the story.

-

Write a one-page summary.

Returning to your one-paragraph summary, expand it further by making each sentence into its own paragraph. End each of the first four paragraphs with a disaster — if you don’t like happy endings, feel free to end the final one with a catastrophe too!

-

Create a one-page character dossier for each major character (plus a half-page dossier for each minor one).

Include everything you know about the character and map out their journey with respect to the main plot in your one-page summary.

-

Finish with a four-page synopsis.

Expand each paragraph in your one-page summary further until you have a comprehensive synopsis.

Q: What tools or methods do you recommend to create comprehensive character profiles?

Suggested answer

This is so important because the character will drive your story.. You reader has to be fascinated by your protagonist and be routing for him or her. I always interview my characters in depth. I don't just ask them about the basics of their lives and history, I ask them what they fear most in life, what makes them get up in the morning. I tool I send to authors I coach is the Proust Questionnaire, not something the great Proust used in his work, but a game that was popular in his time. Here it is:

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

What is your current state of mind?

What is your favorite occupation?

What is your most treasured possession?

What or who is the greatest love of your life?

What is your favorite journey?

What is your most marked characteristic?

When and where were you the happiest?

What is it that you most dislike?

What is your greatest fear?

What is your greatest extravagance?

Which living person do you most despise?

What is your greatest regret?

Which talent would you most like to have?

Where would you like to live?

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

What is the quality you most like in a man?

What is the quality you most like in a woman?

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

What do you most value in your friends?

Who is your favorite hero of fiction?

Whose are your heroes in real life?

Which living person do you most admire?

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

On what occasions do you lie?

Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

What are your favorite names?

How would you like to die?

If you were to die and come back as a person or thing, what do you think it would be?

What is your motto?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I provide all my clients with a template that I devised myself for ensuring that every single character in a novel is fully fleshed-out, colourful and contrasting, both within themselves and to other characters.

Vanessa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I've had success doing enneagram quizzes in each character's persona. Even if you don't believe in personality profiles, it's a good way to check whether a character's goals, motivations, and considerations are consistent. They can reveal gaps where you still have a question to answer about a character's background and, best of all, it reassures you that you're writing characters who contrast with one another, rather than representing different aspects of your temperament as the writer.

Mairi is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Of course, nothing you write at this stage is binding. You can go back and change the details later, but at least you won’t stumble upon major plot holes three quarters of the way into your first draft!

Example: Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn

Mark Dunn’s Ella Minnow Pea is told through a series of progressively lipogrammatic letters sent between the story’s characters. As the government bans more and more letters (the alphabet type), the characters and Dunn must avoid using them and therefore turn to increasingly creative ways of expressing themselves.

This novel lends itself well to the Snowflake Method, as the premise encompasses more or less the entire plot, but lacks specific details. Dunn’s one-sentence summary might be:

More and more letters of the alphabet are banned from use, making communication nearly impossible.

Next, Dunn would ask himself, “Why are the letters banned and how do people react to the restrictions?” This might lead to the following five-sentence summary:

An island society worships the man who created the 35-letter pangram, “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.”

When tiles start to fall off a statue of this pangram, the government bans the use of the fallen letters.

As people try to adapt to the increasingly limited language system, some citizens begin an underground resistance movement.

A visiting American scholar persuades the government to lift the restrictions if someone can come up with a shorter pangram within a set time frame.

On the last day, with only a few letters left intact, a girl stumbles across a 32-letter pangram in a note from her father: “Pack my box with five dozen liquor jugs.”

At this point, we start to see some key characters: the ruler(s) of the island, the leader(s) of the resistance, the American scholar, the girl, and her father. The next step would be to explore those characters’ motivations, goals, and conflicts to come up with their general arcs.

Then, Dunn would expand each sentence above into a paragraph by asking himself questions such as:

- How did the islanders’ religion get started?

- What happens to citizens who accidentally or deliberately use the forbidden letters?

- What actions do the resistance movement take?

- How does the scholar manage to strike a deal with the oppressive government?

- How does the collapse of their belief system change life on the island?

After that, Dunn would be ready to create detailed character dossiers and a longer synopsis.

2. Use the conflict-oriented “What Could Be Worse?” Method

🌟 Best for: writers who know their story’s central conflict but need to flesh it out.

The “What Could Be Worse?” Method is another iterative approach to plotting. In a Reedsy Live session, NYT bestselling author and Reedsy editor Caroline Leavitt explains that all you have to do is take your problem and ask yourself, “What could be worse?” Then, examine the new problem and say, “Well, what could be worse than that?”

Keep going until you can’t think of anything worse or your ideas get ridiculous (remember that a story needs to be believable within the context of the world). As you head towards your worst-case scenario, you should notice that you are naturally introducing new characters, plot points, and interesting details. What sorts of details? Let’s look at an example.

Example: The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft

The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft is another book that’s linguistically remarkable. Written in English, it presents itself as a translation from Polish — the translator, who is a character in the story, peppers the text with footnotes expressing her disdain for the narrator’s version of events.

In the novel, eight translators arrive at an author’s house to translate her latest book, only for her to disappear shortly after their arrival.

Here’s how Croft might have used the “What Could Be Worse?” Method to build her plot around this primary conflict:

This is just the beginning of the process. But already, important plot elements have emerged: the setting, a secondary conflict, a love triangle, and a side mystery.

Of course, there are other directions this story could have gone in — what if the author had left a small child behind or there had been a snowstorm that had trapped the translators inside? To get your creative juices flowing, don’t just go with your first idea; brainstorm as many ideas as you can think of and then pick out the ones that speak to you.

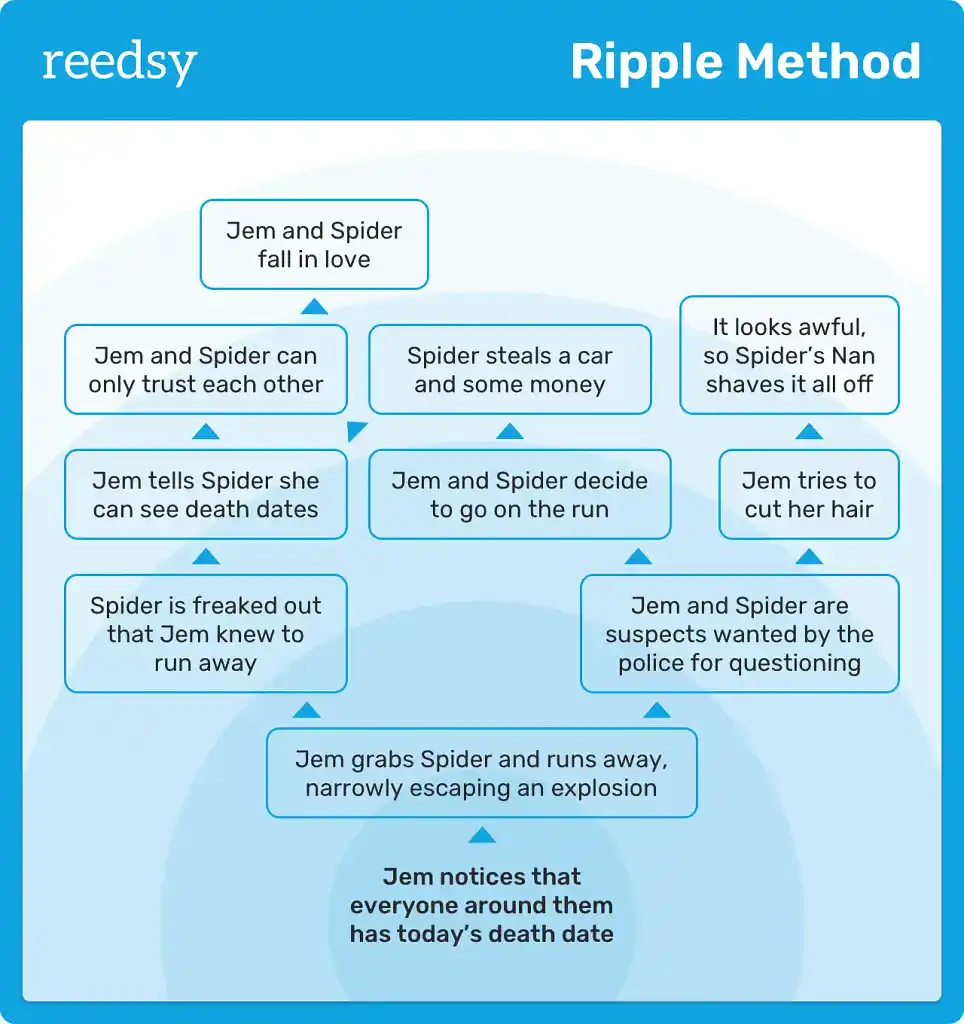

3. Implement the cause-and-effect Ripple Method

🌟 Best for: writers who know their inciting incident but aren’t sure where to go next.

The Ripple Method is inspired by the ripples that slowly spread out across the water when a pebble is dropped in a pond. To plot your story using this method, start with your inciting incident and think carefully about all of its consequences. Then take each consequence and do the same. Repeat until you run out of ideas.

You should end up with a very logical chain of events — though your story doesn’t have to be told chronologically in your narrative.

If you get to a dead end and it doesn’t feel like the end of your story, you can repeat the method again based on a second event. You might find that the chains link together eventually — if not, one of them can always be a side plot.

Example: Numbers by Rachel Ward

Rachel Ward’s YA debut Numbers is about a teenager called Jem who can see the date a person will die when she looks into their eyes. Both suspended from school, Jem is hanging out with her friend Spider near the London Eye when the inciting incident occurs: she notices that everyone around them has today’s death date.

Here’s how Ward might have plotted what happens next using the Ripple Method:

All of this is less than half the story. By the time you complete your ripple diagram, it’s likely to cross multiple pages and have arrows going all over the place. As in the above example, more than one cause can point to the same effect.

Like with the “What Could Be Worse?” Method, you don’t have to actually use all your ideas; you might like to brainstorm multiple possible consequences and then go back through with a highlighter tracing the path(s) that will form your plot.

4. Adopt the character-driven “Wants and Needs” Method

🌟 Best for: writers who have a stronger sense of their story’s character(s) than its specific events.

Caroline Leavitt also recommends this very different approach. It takes its lead from the Rolling Stones song that tells us, “You can't always get what you want, but if you try, sometimes, you might find you get what you need.”

These words of wisdom make for a powerful character arc. To develop your story using the “Wants and Needs” Method, start by thinking about what your protagonist wants and what they need (these shouldn’t be the same!). Then fill out this template:

- The want: What your character wants — or thinks they want.

- The misconception: The mistaken belief your character holds about what they want.

- Action: How the character tries to get what they want.

- The “we're all doomed” moment: When your character realizes they will never get what they want.

- The realization: When they recognize that what they want isn’t what they actually need.

- Starting fresh: What they do next to get what they need.

You might want to repeat the process for other characters and look for where their stories overlap.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

Example: Before the coffee gets cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi

Before the coffee gets cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi (translated by Geoffrey Trousselot) tells four stories set in a café in Japan that allows you to travel back in time — but you can’t change the past, you can’t leave your seat, and you have to return to the present before your coffee gets cold.

The first story is about Fumiko, a woman whose (ex-)boyfriend left her in order to move to America. Fumiko wants to go back in time and stop him from leaving, but needs to accept his decision and stop pining. Here’s how Kawaguchi might have used the “Wants and Needs” Method to plot Fumiko’s story:

- The want: Fumiko wants to travel back in time to beg her boyfriend not to move to America.

- The misconception: Fumiko thinks that her boyfriend chose his work over her. She also thinks that if she had been less proud and had begged him not to leave, her boyfriend might have stayed in Japan.

- Action: Fumiko decides to visit the café so she can travel back in time and say what she should have said: “Please don’t go!”

- The “we're all doomed” moment: The staff tell Fumiko that nothing she does in the past can change the present. She is distraught.

- The realization: After Fumiko goes back in time and talks to her boyfriend, she realizes that moving to America is what’s right for him and she genuinely wishes him success. She also realizes how much she means to him.

- Starting fresh: Fumiko leaves the café with a new mindset: although you can’t change the past, you can live in the present and you can shape the future.

Even though the “Wants and Needs” Method focuses inwardly on character, it inevitably reveals the main turning points of the plot. The action, conflict, and resolution are authentic because they are driven by believable human behavior.

Whichever method you choose, you should end up with your main character(s) and your most important plot points. This means you’re now (and only now) ready to match up the parts of your story to the key elements of plot and start outlining.