Blog • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

How to Copyright a Book in 7 Simple Steps [Updated 2025]

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →So you want to copyright your book and protect yourself from intellectual property pirates (and other potential threats on the publishing high seas)? You’ve come to the right place.

Here’s the simple 7-step process on how to copyright a book:

1. Go to the U.S. Copyright Office website

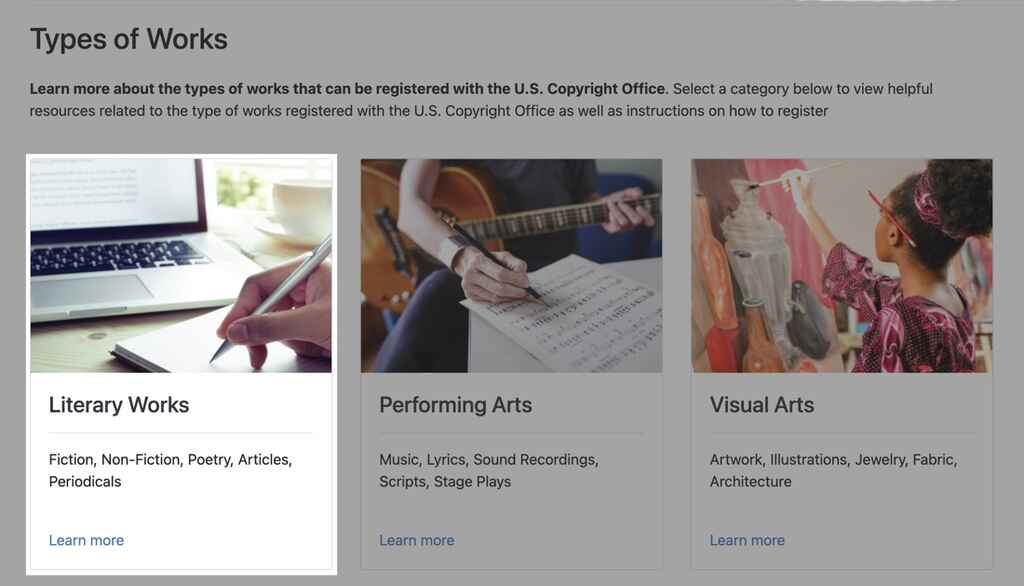

2. Select the “Literary Works” category

3. Create a new account

4. Start the copyright registration process

5. Fill out the details

6. Complete the copyright application

7. Submit your work to finish copyrighting your book

With the help of actual intellectual property lawyers, we’ll also take a look at what copyright is and discuss the all-important question of whether it’s worth the $45 cost for you to register it for your book.

FREE RESOURCE

The Guide to Copyright Registration

Protect your intellectual property with this comprehensive checklist.

What is copyright?

Copyright is just that: the right to copy. When books are published, it’s copyright that prevents others from copying your work and selling it (for profit or otherwise) without your consent.

Protection under copyright is the government’s way of saying, “Hey, this book is your original creative work! What’s more, we can ensure that this book will remain your original creative work and intellectual property — even after you’ve published it in the public sphere.”

So as the copyright owner, only you have:

- The right to reproduce or make copies of your work

- The right to distribute copies of your work

- The right to create a derivative work

- The right to display or perform your work publicly

What doesn't copyright protect?

Copyright protects your expression of ideas or facts. For authors, this extends to specifics of your characters, worldbuilding, plots, and dialogue.

Copyright does not protect ideas or facts themselves. If you’re writing a book, you’ll know it’s a trial to avoid certain tropes — almost all stories are derivative in some shape or form. Below are examples of “idea recycling” that are NOT examples of copyright infringement:

- Neil Gaiman once wrote a book about a young bespectacled boy who discovers magic, obtaining a pet owl in the meantime. He wrote it seven years before J.K. Rowling introduced kids everywhere to Harry Potter.

- Pretty much every popular fantasy novel borrows something from Lord of the Rings; Terry Brook’s Sword of Shannara is the most obvious example.

- 1984 by George Orwell lifted its plot and conclusion from We, a book written by an obscure Russian author, Yevgeny Zamyatin.

In the world of comic books, there’s many a young boy who goes through some traumatic event, coming out on the other side with superpowers. That’s an idea, so it won’t come under copyright protection. But if DC Comics creates an uncannily fast-talking, silk-slinging teenager who swings around a city yelling, “I’m your Friendly Neighborhood Silkman” — all the while copying some specific elements of Spiderman’s story? Then Marvel will probably get mad and there will almost certainly be trouble in Metropolis when they come after DC.

So what matters is the way in which you put your ideas on paper.

What authors must know about copyright

Perhaps most importantly, you should know that copyright protection on an original work exists in the United States and the United Kingdom the moment you create that work (and extends for 70 years after your death). You could be writing the next Great American Novel or just a single sentence — either way, you own the rights to the words as soon as they're written.

But if an author’s work is protected as soon as they commit words to paper...

Why is it important to copyright a book then?

When people say “you should copyright your book,” they usually mean “you should register the copyright to your book.” This is an official process you undergo on the U.S. Copyright Office’s website, which will also cost you $45.

But now you might be wondering: if an author’s work is protected as soon as they commit words to paper, why do you then need to register your copyright — at a $45 cost to boot?

It’s simple: because registered copyright offers statutory protection. With registered copyright, you are entitled to statutory damages, which means that you can get a meaningful payout of up to $150,000 (plus legal fees) regardless of how much money you've lost — and how much the infringing party has made from your work. If you don’t register your copyright, that’s much harder to prove in a court of law.

In short, registering a copyright is like buying insurance.

How to copyright a book in 7 steps

1. Go to the U.S. Copyright Office website

You can find the US Copyright Office’s landing page at copyright.gov/registrations. There is the option to submit a paper application, but the cost is significantly higher ($125 filing fee) and you may have to wait between 10 and 15 months for processing.

2. Select the “Literary Works” category

If you’re looking to copyright anything primarily intended to be read — not lyrics, or a screenplay — click on Literary Works then Register a Literary Work on the next page.

3. Create a new account

You will be prompted to sign in to the Online Copyright Office if you already have an account. If you haven’t registered a work through this site before, just tap the link that says If you are a new user, click here to register.

On the next page, you’ll be prompted to enter your personal information, as well as a new USER ID (user name) and password.

You can register your copyright under a nom de plume later, so don't worry too much about using a legal name or another alias at this point.

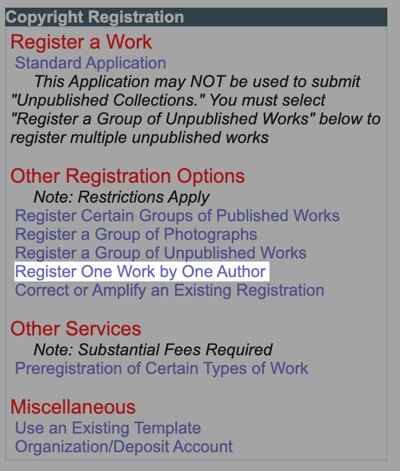

4. Start the copyright registration process

Once you’ve logged in, tap the Register One Work by One Author link under Copyright Registration. This will allow you to access the $45 registration option, rather than the standard $65 cost.

Note: the Copyright Office’s website advises you to use the Firefox browser for best results. Having tested this on all other major browsers, we can confirm that the Copyright Office's site is just as ugly and outdated-looking on all of them. Don’t worry, though. You won’t be here for long.

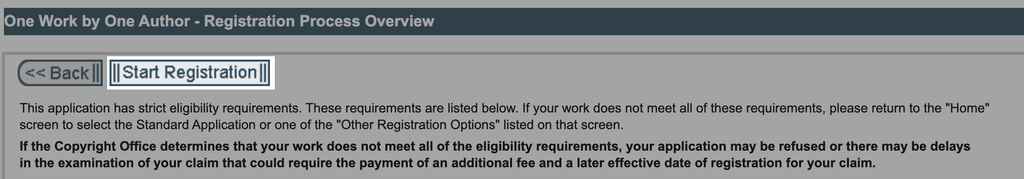

Assuming that you’re just registering one book (and that you are the sole author and copyright holder), hit Start Registration on the next page.

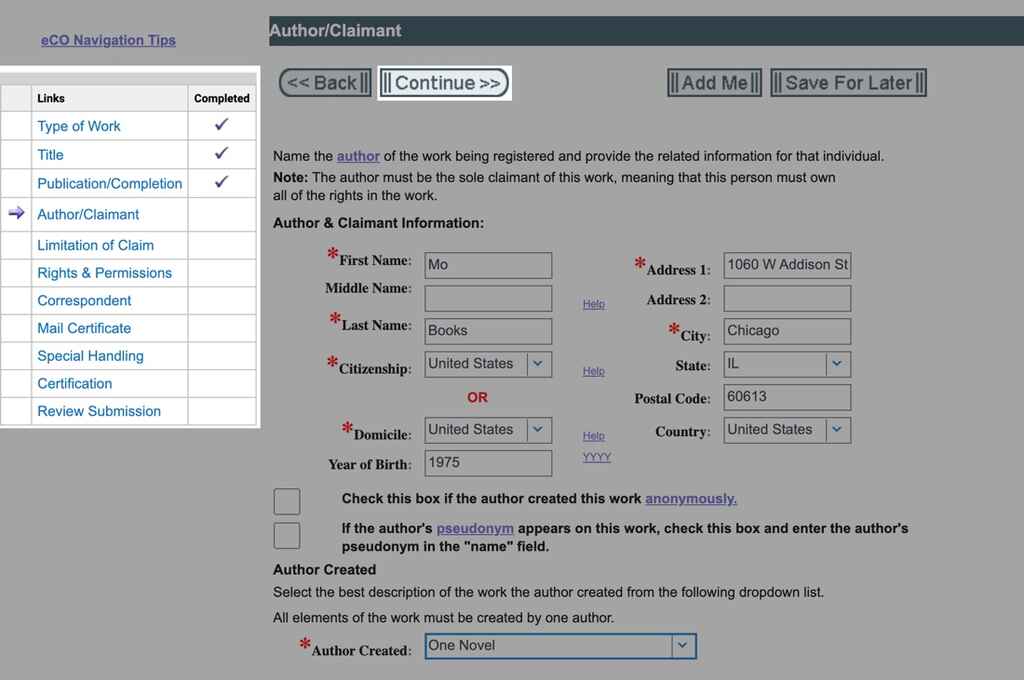

5. Fill out the details

The next stage simply requires you to fill in the details of your book, hitting the Continue button after each stage.

Once all the details are filled in, and you have reviewed your submission, hit the Add to Cart button at the top and you’ll be taken to the payment page.

6. Complete the copyright application

In your online ‘cart’, click the Pay - Credit Card/ACH button and you’ll be directed to the US Treasury’s website where you can complete your payment either by credit/debit card or direct deposit.

7. Submit your work to finish copyrighting your book

Once your payment has been confirmed, you will be prompted to submit a copy of your book. The Copyright Office requests authors to send in the “best edition” available of your book. Depending on how many editions you have, this will mean:

- A paperback version, rather than the digital version

- The hardcover edition, rather than the paperback.

In short, they want the nicest, shiniest version of your book that you have on offer.

Congratulations! You’ve just successfully registered your copyright, and you can rest easy knowing that you’ve done everything you can do to protect your work in the future.

At this point, you may be still wondering...

Is registered copyright necessary for your book?

It’s important to remember that the chances of somebody illegally infringing upon your work are extremely slim. The vast majority of professionals (we can’t emphasize this enough) will respect your book for what it is: an original work that’s not to be stolen from.

Still, there remains a non-zero chance that someone will infringe on your rights in your future, just as the odds are 1 in 75,000 you’ll get struck by a comet or asteroid in your lifetime. So whether or not you take the step of registering your copyright will depend on whether or not you believe that your peace of mind will be worth the $45 cost.

Where you are in the world matters as well. While the U.S. Copyright Office strongly recommends registration for all authors, it might not be the case elsewhere. For instance, there is no U.K. equivalent! If you’re self-publishing in the U.K., all you need to do is mail a copy of your work to the Legal Deposit Office of the British Library within one month of publication.

As always, arm yourself with more info if you’re in doubt. Writers Beware, which is sponsored by the SFWA, is always a dependable place to get contract advice. We especially are fans of their Basic Copyright page and this blog post. And for more information on photography usage and whether or not you should register the copyright for a book cover, check out this post over on Book Design House and this post on CreativIndie.

Special thanks to the attorneys who contributed to this post and provided their knowledge:

- John Mason is an intellectual property attorney specializing in creative and entertainment industry copyright cases. Contact John at www.copyrightcounselors.com or jmason@copyrightcounselors.com.

- Sean Lynch is an intellectual property attorney who provides copyright and trademark advice to clients building businesses and brands. In addition, you can find Sean at slynchlaw.com and thesurflawyer.com.

- Henry Runge is an Associate Director of UNeTecH. He protects scientists' inventions and works with entrepreneurs and creatives to develop business opportunities for intellectual property.

Finally, to read about the topic straight from the source, visit the U.S. Copyright Office, the U.K. Intellectual Property Office, and the Australian Copyright Council websites.