Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

Character Motivation: How to Write Believable Characters

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →If an author wants to focus on making their stories more believable, it’s crucial for them to fully understand character motivation. Readers will happily accept and suspend their disbelief for any story — whether set deep in space, or in a society run by terriers — so long as all the characters have relatable motivations and behave plausibly.

In this post, we’ll look at some of the big questions behind character motivation in fiction and help you understand why it’s important and how to apply it to any book you are working on.

What is character motivation?

Character motivation is the reason behind a character’s behaviors and actions in a given scene or throughout a story. Motivations are intrinsic needs: they might be external needs and relate to survival, but they might also be psychological or existential needs, such as love or professional achievement.

This motivation is at the heart of character profiles and is necessary if your goal is to write believable and compelling characters.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

Why is it important to understand character motivations?

If you’re writing a short story, novel, song, or even a haiku that features a character, you need to pay attention to motivations for the following reasons.

1. Motivations make it easier to put yourself in the head of a character.

You know the old cliché of actors asking for their ‘motivation,’ right? They sometimes call it a “playable note” and it’s something that can help you write believable characters.

Ask an actor to deliver his lines ‘desperately,’ and they’ll lay on the motions of desperation (stammering, agitation, etc.) — but if you tie it to a playable motive like “if the customer doesn’t sign the contract, you’ll be fired and your family will be evicted,” then they have something to really incentivize them.

As an author, it’s tough to write an “angry” character — much better to create a situation that frustrates their motivations, resulting in their anger. So give yourself a playable note.

2. Every character needs to have motivations, no matter how unlikable they are.

Writers tend to be pretty good at creating the trajectory of a protagonist while forgetting to flesh out an antagonist. Why do they do this? “Being evil” is not good enough. When was the last time anybody did anything for the sake of being evil?

If you keep going down this rabbit hole, you’ll soon realize that relatable villains are much more interesting and terrifying than ones who care about senseless, abstract villainy.

3. Readers need your character’s motivations to be credible.

Readers don’t have to like, approve of, or share a character’s motivation — they just have to believe it. As writer and blogger Ryan Lanz says in this post on which story elements to establish right away, character motivations are critical to getting readers invested: "Who do you know in life that doesn’t want something? Exactly. Everyone wants something, and so should your characters."

Without credible motivations, your characters will read like strange puppets that you’ve dressed in human clothing. So bring them to life and give them real, understandable reasons for doing what they do.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

What are a character’s motivations?

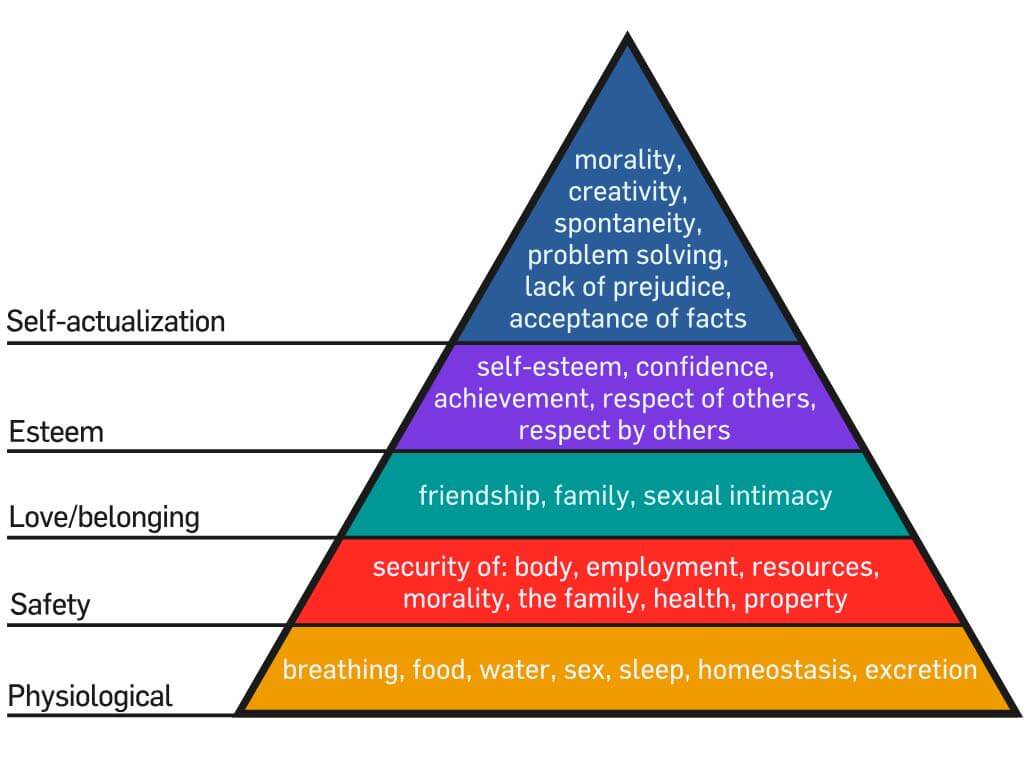

In her fantastic post on motivation, author Kristen Kieffer uses Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Need” as a way to explain character behavior. An American psychologist working in the mid-20th century, Abraham Maslow proposed many human ‘wants’ and prioritized them from basic survival needs to existential desires like self-actualization and morality.

(Sidebar: It’s interesting to note the impact psychologists like Maslow, Freud and Jung have had on modern storytelling)

In recent years, Maslow’s model has been simplified in a way that may be more useful to authors, breaking his tiers into three categories.

Basic needs:

- Food

- Water

- Shelter

- Sleep

- Security

- Safety, etc.

Psychological needs:

- Love

- Friendship

- Accomplishment

- Acceptance

- Self-esteem, etc

Self-Fulfillment:

- Self-actualization

- Creativity

- Achievement of potential

Maslow’s theory suggests that all basic physiological needs (and most psychological needs) must be met before a person starts to focus on any higher purpose like creative fulfillment. There has, however, been debate over the strict hierarchy he's placed upon these motivations. The most important thing to take away from this is that all human behavior should derive from an inherent “need.”

The difference between a goal and a motivation

Goals and motivations are commonly confused, and understandably so: they’re both things that relate to a character’s ‘wants,’ and they both can drive a character and their story. Perhaps the simplest way to think about it is this:

- A ‘goal’ is something that a character wants to achieve. It is a conscious objective like getting rich or winning the World Cup.

- Motivation is the underlying reason why a person has that goal, like the fear of being financially insecure or the need to prove themselves as someone exceptional.

Winning World Cups is not an intrinsic human need, whereas self-actualization is.

In fiction, you’ll notice that characters can share an identical goal — while having motivations that are worlds apart.

In a psychological thriller, a detective might be hunting down a serial killer:

- Before he becomes the next victim (basic need).

- To salvage his reputation in the force (psychological need), or

- To prove himself to be the greatest detective (self-fulfillment).

A bank robber might be planning the heist of her life:

- To save her family home from being sold (basic need),

- To pay for surgery to restore her partner’s eyesight (psychological need), or

- To prove to her mentor that she has what it takes to pull off a big job (self-fulfillment)

In both these scenarios, the goal is the same, but the motivations change.

Do all character motivations have to be rational?

Motivations in fiction don’t need to be rational — after all, humans are incredibly irrational.

If you had to sort all the motivations listed above into two categories, you might label them ‘fear’ and ‘love.’ Fear of death, hunger, abandonment; love of others, success, prestige. Fear and love both have the ability to be irrational — except we might call them phobia and infatuation (or obsession).

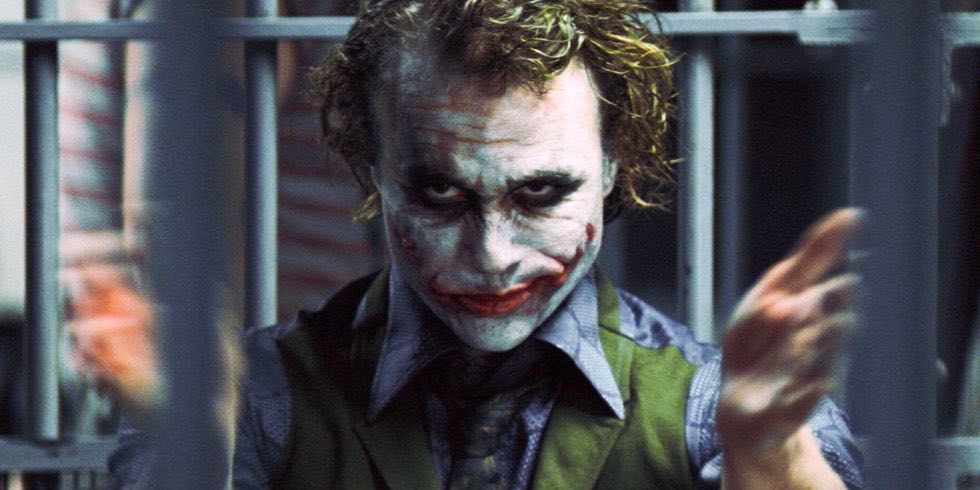

Once you accept those irrational motivations as legitimate, it’s then a matter of applying internal logic. That’s what you’d do if you were writing, for example, a sinister psychotic villain.

The Joker in The Dark Knight wants to throw Gotham into chaos — a grand plan that might stem from a psychological or self-fulfillment need to re-create the city in his image — whatever it is, it's not something that most of us can relate to. However, once we accept that it is what motivated him, what we then care about how he goes about achieving this irrational goal is methodical and logical: corrupting Gotham’s heroes in front of the city’s eyes.

So motivations don’t have to be rational — they just need to manifest themselves in plausible ways and subscribe to some amount of internal logic.

Does the reader need to know a character’s motivation?

Not explicitly, but in a well-crafted book, a character’s motivations can become clear through expository passages and dialogue, or are suggested through action and descriptions. If a sidekick is seen preening and combing his hair, for example, we might gather that he is vain — and when he later refuses to help our protagonist dig through the trash, we might chalk it up to an internal motivation to protect his dignity in front of others.

Readers don’t need to understand the inner machinations of every minor role in a book. But an author’s awareness of what motivates their characters (like, say, the silent waiter standing the corner of the room) greatly improves the chances that they won’t just be clichéd cardboard cutouts.

Can a character have conflicting motivations?

As we’ve mentioned many times before, conflict is at the very heart of storytelling and is essential for creating a rounded protagonist or antagonist.

If a protagonist wants just one thing, and the only thing stopping them from getting that thing is an external conflict, then their journey is simple: defeat the antagonist and win the day. It’s only when the main character has multiple motivations and they are forced to choose between them that we can see a character’s true nature shine through.

Creating suspense with conflicting motivations

In The Hunger Games, young Katniss Everdeen is a skilled hunter thrown into a deadly televised game. To survive, she must kill her fellow competitors, including innocent children and her close friend. From this description, we can see that she has two basic motivations:

- To stay alive (basic need)

- To preserve her moral code (psychological need)

From just these two elements arise the book’s central conflict: how will Katniss survive without sacrificing her friends and principles?

Without conflicting internal motivations, a character’s journey would be too easy and, therefore, dull. Rocky would just be a film about a boxer who trains a lot to overcome a better opponent — which is boring. Instead, it’s about a man’s attempt to prove himself a worthwhile human and worthy of a woman’s affection while also dealing with his fear of failure. That is the conflict driving the story — not the boxing.

For some writers, character motivation comes easy — their instinct is to think about how their characters would behave in a certain situation (and not how they think they should behave). If you find yourself struggling to bring your characters to life in any given scene, try using these character development exercises. It always helps to ask: what do they want? In this scene, and in general. Once you’ve nailed their motivation, your characters should hopefully show you where they need to go.

If you have any thoughts, questions, or theories on character motivation, please drop us a message in the comments below.

2 responses

PJ Reece says:

22/08/2018 – 17:31

Thanks, Martin... my characters tend to discover deeper motivations as the story unfolds, which gives the impression that the goal posts are shifting, which I guess they are, and I like that, but some readers may get left behind. This writing thing is hard to master, as Hemingway acknowledged -- something about no one ever having done so. Oy.

Lexi Mize says:

22/08/2018 – 19:37

What do you need vs what do you want.