Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

Worldbuilding: Create Brave New Worlds [+Template]

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Worldbuilding is the process of creating a fictional world's history, geography, politics, culture, and social structures. Because it's fundamental stage in the writing process, particularly for genres like fantasy and science fiction, authors are recommended to approach it as if the world itself as a character. They can do so a few different ways: inductively, or building a world around a story, or deductively, building a story within a world.

Since creating a fictional universe is a daunting task, you might want a bit of help. Here's how to worldbuild in 7 steps:

We’ve also created a template to help you in your process, which you can download for free.

FREE RESOURCE

The Ultimate Worldbuilding Template

130 questions to help create a world readers want to visit again and again.

1. Define your world’s name and setting

Broadly speaking, the setting of your story will either be our own world, or an entirely fictional world — what’s known as “second world” fantasy. Before you start work on your backstory, it’s essential to know which of these categories your story will fall under.

Create second worlds from scratch

George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and Raymond E. Feist’s Riftwar cycle are classic examples of “second world” fantasy: they were able to create worlds untethered by historical paths or laws, which gave them a lot of freedom of choice.

Q: What are some of the biggest misconceptions first-time authors have about writing fantasy?

Suggested answer

Fantasy, and in particular romantasy, is SO HOT right now. Everyone is writing it, but many new authors fall into the trap of exposition. Just because you're writing in a unique setting doesn't mean you have to explain this world to readers. At least, not all at once, and certainly not all in the first few chapters.

Fantasy especially can span multiple books and because you're already telling a unique story about unique characters, it's overwhelming and exhausting for readers to also swallow a unique world.

The best solution is show, don't tell. Let it happen organically, and at natural moments in the story. For example, a wizard walking into a cauldron shop may merit a few sentences as to why he's buying a new cauldron, but probably doesn't need the extra two pages of exposition regarding the cauldron's connection to his late mother, who was also a half-fae princess and died at the hands of his tyrannical father, but only after having a torrid affair with a werewolf whose daughter now owns the very same cauldron shop.

Alexandra is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You still need strong characters that propel the story forward. The fantastical elements don't replace a strong personal journey or transformation of your protagonist.

The fantastical elements you include should also have purpose and be used with intention. If there's a magic system, it has to make sense in the world. Magic can affect economics, culture, politics, and it should be reflected on the page.

With kidlit, take a look at fantasy published within the last few years. Western-based fantasies with gnomes, trolls, etc. are generally not unique enough to attract an agent or publisher's attention. Readers want to read about completely different worlds with unique magical/fantastical elements.

The best way to get a handle on today's fantasy and what agents and publishers might be interested in is to read titles published in the past couple years.

Kim is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For me, the main misconception is that the story world is the story. No. The characters are the story, no matter the genre. Fantasy authors can get too wrapped up in the world they have created - and why wouldn't they? It's an exciting thing to create - to the detriment of their story. So it's really important to, at some point, turn away a little from your story world and turn to your characters. Do they have motives? Goals? Fears? Desires? Secrets? Regrets? Flaws?

All the things that make us human (even if your character isn't human!) need to be on the page. It's very easy to lose sight of character and plot when writing fantasy, but no matter how outlandish, or unique, or captivating, your story world is, it's the characters who inhabit your world that truly count. It's the characters readers recall more than anything else. So my advice to fantasy writers is character first, always.

Louise is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Whenever a story leaps from the present day into a new world in another time, there has to be much more time, and therefore words, spent on world-building. The reader must be able to get a strong sense of this new world right away with sentences depicting the scenery and setting, what the characters look like, and how modern or primitive this new world is.

So, a misconception could be that coming up with a strong and unique plot line or characters is enough. While these are all necessary, everything in the "new world" must all make sense and be clear, and easy to understand. It must all be logical, and that takes time to plan. So, spending time planning and building up this new world with all of its new rules and exciting twists is something authors will also need to spend a fair amount of time on. And this goes beyond a basic outline or plot points.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This creative freedom is exciting, but it also requires a lot of world building work to invent a fleshed out and textured fantasy world. A strong starting point in order to define your world as “other” to our own is selecting your world’s name. You can make it as cool as you like; think Discworld, Middle Earth, Zamonia, etc.

Set your story in an Earth-like place

Not all fantasy writers, however, wish to create an entirely new world. You can always set your story right here on Earth. For example, the vast majority of literary fiction, mystery, and romance novels are set on a place called Earth that bears a striking resemblance to our own world. This kind of world creation may require less invention on behalf of the author, but may require just as much preparation as they are constrained by historical specifics, technology, and politics.

Within “real world” fantasy, however, you will see two broad subgenres: alternate history fantasy, and historical fantasy.

For historical fantasies, while some amount of historical license is accepted (and encouraged), your readers will notice something’s wrong if your book has Atilla the Hun kidnapping Florence Nightingale without the help of a time machine.

Q: What daily writing routines can help authors maintain consistent productivity?

Suggested answer

+ Never underestimate the power of enough sleep. This can cure more things than we know - how we show up, what we're capable of tackling each day.

+ Nourishing food to fuel the mind.

+ Movement - even if it's a walk around the block listening to a podcast, music or just deep in thought (often the best times when ideas arise).

After these three things are locked in:

+ Quiet, undistracted time blocks (even if it means phone in another room for 90 mins)

+ A laptop that has nothing else except Word on it (no website access).

+ For those who are visual, keeping a yellow sticky note daily "checklist" on a wall, to encourage a daily writing tally.

+ Ask for feedback for continual improvement.

Leoni is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There are four things that I consider before settling in to write.

What sounds are there? The best is silence, but in a city environment this is impossible. If there are specific loud that I want to block out, I listen to drone music. This consists mostly of long, sustained notes (no melodies) and comes from the American and German post-war experimental musical traditions. The texture of the sounds is often rich which works for this purpose quite well. It has a meditative effect. Failing this, music without lyrics is also good.

What is my phone doing? Just switch it off.

Social media. Along with my phone, this is designed to distract. What I do is log out of my social media accounts. If I automatically go back in, I'm then met by the login page. This doesn't sound like much of a difference, but is just enough to nudge myself into becoming mindful of what I'm doing and what my present purpose it. And mindfulness is key.

Lastly, I take a page of Hemingway's advice: "The first draft of anything is s**t." It's ok to produce bad writing. In fact, it's totally ok; actually it's great. Why? Because my ideas are now down on the page, even if it's absolutely horrible. Nobody ever simply writes a finished product straight off the bat. I'll make it better later and that is a different process.

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Get all domestic and admin chores out the way first, so that there is nothing else on your mind when you sit down to write. Then just stick at it for as long as possible.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Alternate history fantasy gives you a little more freedom; as the name suggests, you’re inventing an alternate version of history. Still, you’ll want to think carefully about the changes you’re making, and the way they might impact the day-to-day life of your characters.

Once you’ve selected between first and second world settings, you can begin building it in earnest. This is where the fun really begins.

Watch: How to create your worldbuilding bible

2. Create a map of the territory

Once you’ve named your world, it’s time to fill it. That means having at least a broad sense of its geography and ecology, so that you know what the landscape looks like, and what beasts your characters are likely to encounter.

You can consult our worldbuilding guide for a full list of prompts, but some questions to consider include:

- What sort of environment can be found in different areas of your world? (Deserts, oceans, mountains, forests, etc)

- What wildlife can be found there?

- What is the climate like?

- Where are the cities? How large are they? What are they called?

Take inspiration from real countries

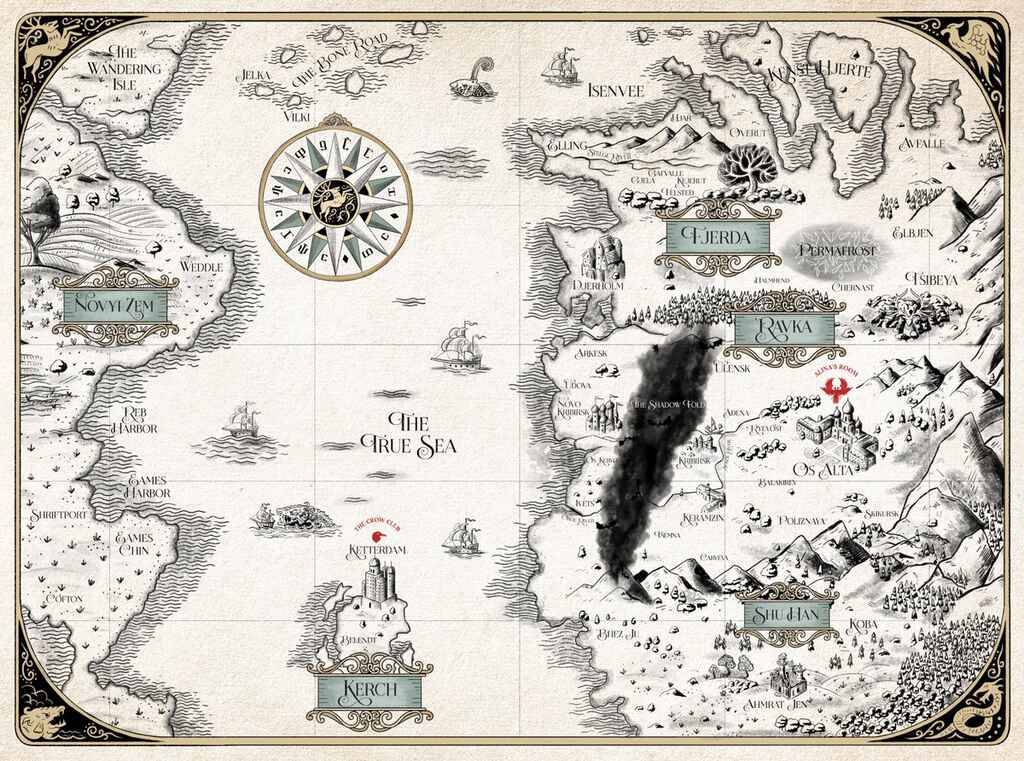

You can draw from the real world when imagining these aspects of your fantasy world. For example, Leigh Bardugo’s Grishaverse takes inspiration from the geography of a number of real-world countries, often at another point in their national history. You can find analogs for Tsarist Russia, the Dutch Republic, China, and Scandinavia in Bardugo’s books.

As well as drawing from the past, another approach could be to imagine a future iteration of our world. NK Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy is a masterful example of speculative worldbuilding. The trilogy takes place on a supercontinent called the Stillness, which is wracked by massive climate events every few centuries which reshape the entire world’s geography. Colson Whitehead’s Zone One is set in the familiar but decimated remains of a future New York, a cityscape that has been devastated by a zombie apocalypse.

Maybe set your story in two different places

Another possibility is to create a dual setting, locating your narrative in part in our own physical world, and in part in another. Erin Morgensen’s The Starless Sea tackles this expertly, using the classic “magical door” trope to connect her real-world locations (Vermont and New York) with her fantastical world, the honey-filled Starless Sea and the magical harbors that sit upon it.

Q: How can authors protect their rights when publishing, especially in the age of AI?

Suggested answer

I don't think anyone can fully protect themselves. If you act in good faith you will find that most other people will do the same. There will always be rogues, but selling books is hard enough if you are the real author, even harder if you have stolen it.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Imagine an entirely new environment

You may, of course, wish to create a landscape entirely alien from our own. Frank Herbert’s Dune is set on the desert planet of Arrakis, a world entirely devoid of natural water and inhospitable to most forms of life. Noteworthy exceptions to this are sandworms, giant and dangerous worm-like creatures that Fremen, the planet’s inhabitants, have learned to ride.

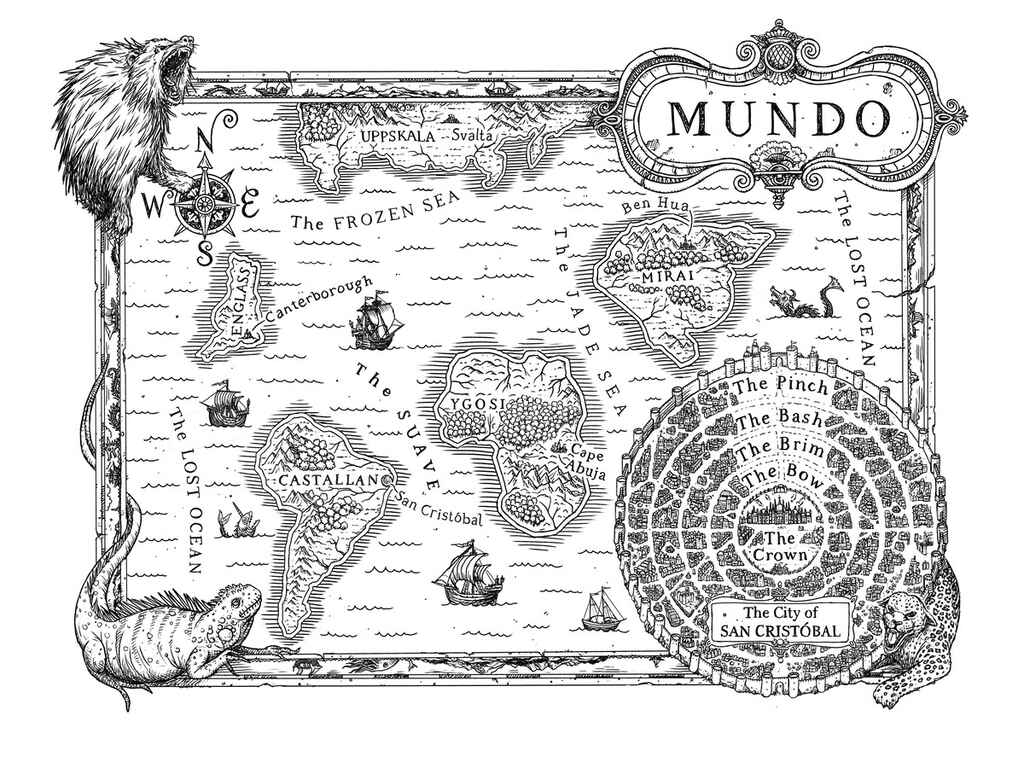

Lots of fantasy readers like referring to a physical map when imagining a world that is unlike our own. Maps are not always necessary, but they’re a useful foundation to define a sense of distance and space — and they can help you visualize your world as you’re building it.

Draw a map to help the reader

For a personal and expert approach, it's definitely worth hiring a professional illustrator to develop your fantasy map. Here at Reedsy, we have rigorously curated the best freelance illustrators in the publishing business — and they're just a click away from helping your work stand out.

🐲 Get your world right by hiring a pro fantasy editor

Helen L.

Available to hire

Literary Agent and Developmental Editor. I represent incredible authors at Ki Agency. My editorial focus is on Fantasy, Sci Fi and Romance.

Chris U.

Available to hire

I am an expert in genre fiction, with years of experience evaluating short fiction. I want your wildest stories to find a published home.

Laura S.

Available to hire

Editor and published author (Penguin Random House, Simon and Schuster) with over a decade of experience. Expert in novel and query edits.

3. Populate the world with people

Now that your physical landscape exists, let’s drop some people into it. To create a textured and believable setting, you’ll want to populate your planet with a variety of races and cultures — which can be either created, or based on real-world cultures.

You may wish to pull species from the rich traditions of high fantasy (elves, dwarves, trolls, etc), but you can also invent entirely new races. Our worldbuilding template will help you nail down the details of your inhabitants.

Be careful with tropes and stereotypes

Make sure to research thoroughly before settling on any attributes or characteristics for your characters. Even in the imagined worlds of fantasy and science fiction, harmful stereotypes can be perpetuated, especially when drawing on real-world cultures.

Some research is therefore required to ensure you are handling your source material in a respectful way, and to avoid retrograde stereotypes when portraying the characteristics of imagined races (including “classic” fantasy characters like dwarves, which have long been influenced by antisemitic tropes).

An example of real-world cultures informing fantasy cultures is the setting and characters of Children of Blood and Bone. Author Tomi Adeyemi draws on African mythology and her own Yoruba heritage, setting the story in a fictional version of pre-colonial Nigeria. Her imagined country, Orïsha, is inhabited by two peoples; the magical divîners with distinctive white hair, and their non-magical oppressors, the kosidán.

Q: How can writers use stereotypes and tropes to their benefit when creating a character?

Suggested answer

Well, stereotypes and tropes exist because they are the comfort food of readers, and should be the comfort food of writers too. Not to the extent that you write cliche stories by overusing the same old thing. But by the fact that their presence in certain story types is expected and even desired by fans of that story type, so to try and write without them can leave readers unsatisfied and the story feeling incomplete.

There are great books out there on this, John Truby in particular has a great one out. Knowing the stereotypes of a heroes journey, for example, gives you lots of options for side characters and supporting characters to help a hero on certain types of quests. The tropes are the expected encounters and obstacles that hero will encounter along the way.

If you start by mapping these out and identifying which are required (tropes most of all) and which work best for your story but are optional (stereotype characters) then you can take them and twist them in unique and interesting ways, even flip them around in timeline or approach in ways that make it clear they are there (and meet reader expectations and preferences) while still avoiding cliche expectation and creating interesting and unique characters, world, and stories that captivate readers.

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Trope = yes

Stereotype = no

A stereotype is an oversimplified view of a type of person, based on one aspect of their identity, like race or gender or hair color or where they're from. It's important to know stereotypes so you can avoid them in your writing, both so you won't be generic and so

Tropes, on the other hand, are like adding sugar to cake, rather than salt: You want to know what your audience came for, so you can give it to them!

Tropes are things with universal appeal that audiences come back for time and time again. (Not to be confused with a cliche, which is just something that has been overused until it's cringey. For instance, the villain in a YA novel being a mean blonde cheerleader is both a cliche and a stereotype. But a trope might be that the main character is an underdog who manages to win the heart of the most high-status boy in school!) Examples: enemies to lovers, amateur detective, chosen one, only one bed...

Intelligent use of proven tropes, combined in a new and unique way, are the fastest way to genre writing success!

Michelle is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A trope is something that is instantly familiar to readers: a character type, setting, plot point, or style of writing that is recognizable and tied to a specific genre.

For example, one familiar romance story structure is the “enemies to lovers” plot. This pattern is immediately recognizable to readers, and although it is used often, writers are still finding new and unique ways to spin it, and readers still love engaging with it.

Another popular trope is that of “The Chosen One.” Think about it: Both Luke Skywalker and King Arthur find a magical sword, receive the guidance of an older, wiser mentor, and go on a journey to storm a stronghold to save a princess. Even though the building blocks are the same, the stories are vastly and entirely different…and centuries apart!

There are hundreds of ways to apply this trope and come out with a unique and fresh story.

Tropes are the conventions, ideas, or motifs that make up these basic building blocks of all storytelling. In order to tell a fantastic story, tropes are necessary (and not to be confused with clichés, which are devices, expressions, or phrases that have been used so often and in so many places that readers have become tired of them, and desensitized to them). But why are they necessary?

Well, tropes are baked into every genre that we know and love. If you’re writing a western novel, odds are you might have a lone cowboy or a bumbling sheriff in there. If you’re writing a thriller or mystery novel, you might find yourself creating a gritty, lone-wolf detective, who acts first and asks questions later. Just because these tropes have been used before, doesn’t mean they’re tired!

If you’re writing in a specific genre, in order to use tropes effectively, you should be intimately familiar with the tropes of that genre. Knowing them inside and out means you’ll have your best shot at subverting them and spinning them in new ways that readers will enjoy (and avoid veering into cliché territory).

Think of books in the genre that you’ve read before. Was there one that you didn’t like? Ask yourself: What specifically made you dislike it? It might be that a trope wasn't used effectively, and if you can identify exactly what disappointed you about the way that trope was used, it can help you discover what you wished that writer might have done differently. And then: poof! Suddenly you have a thread of inspiration you can pull on to get some ideas for your own story.

Remember: tropes are patterns. And patterns can be twisted, bent, and manipulated. Just be careful not to break the pattern, or you risk readers finding it difficult to relate to a trope they cannot recognize and therefore relate to.

Writers just like you are still finding fresh ways to put a spin on tropes of all kinds, and using those building blocks to build entirely new and unexpected things for us to read!

Lesley-anne is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When it comes to building characters, tropes and stereotypes get trashed. Authors shy away from them, not wanting their stories to sound stale because they're leaning on well-worn tropes. But applied sparingly, these storytelling crutches can enrich your characters, allow readers to jump in easily, and even lay the foundation for surprise and depth.

Tropes are a short-cut for your readers. They give readers a feeling of who a character is and where they stand in the story. A "mentor," for instance, gives a feeling of guidance, a "reluctant hero" gives a feeling of inner conflict, and a "grizzled detective" gives a sense of experience and exhaustion. These archetypes shave space out of your storytelling so readers can catch on to relationships and dynamics immediately. The art is to combine them with unique characteristics that make your character stand out.

Stereotypes are worse. They can establish context rapidly, but they can also be lazy or toxic if they are not challenged. The trick is to use them as a springboard, and not an endpoint. A character who holds the "shy bookworm" description might secretly be a social master manipulator. That interplay between expectation and reality keeps things interesting and provides depth.

Another great way to use tropes is to subvert expectations. Use a "princess in distress" who saves herself or a "charming rogue" who has imposter syndrome. By turning the expected tropes on their head, you catch the reader off guard without losing respect for those conventions.

Ultimately, the most compelling characters are born from layers beyond the trope. Surface traits like charm, wit, or wisdom draw people in, but motivation, flaw, and contradiction create a character. Tropes will also support your themes—whatever they may be, from redemption to generational insight to ambition's cost—adding cohesiveness to your narrative but still permitting complexity.

The issue happens when writers rely on tropes or stereotypes without questioning them. Does every single one serve the story, add depth, and make your character more human? Used consciously, tropes and stereotypes are not clichés—they are tools used to make your characters immediately recognizable, resonant at a thematic level, and unforgettable.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

While it's worth noting the use of tropes and stereotypes can be comforting -- I love an enemies-to-lovers, "Who did this to you?" trope in romance, and the Chosen One in young adult makes me nostalgic for the golden age of dystopian; however, you can also use stereotypes and tropes by subverting them.

A great example is Victoria Aveyard's RED QUEEN. I won't reveal the twist, but it took a certain romantic stereotype, crushed it to pieces, and surprised readers in a way that still gives me (delightful) trauma! Another more general example is the Game of Thrones series and the way that George RR Martin kills characters off left and right. Those you thought were heroes or "chosen" are not guaranteed to be around long enough to fulfill any destiny.

So by all means, embrace tropes and stereotypes to give readers what they want; however, think about surprising them a little bit. See how you can tell a different story.

Grace is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There is a common misconception within writing circles that "trope" = bad or cliche. While yes, certain tropes and character traits can become overused and cliche, tropes are more like reader expectations when they pick up a book from a certain genre. For instance:

- In romance, tropes are things like friends to lovers, enemies-to-lovers, he falls first, grumpy neighbor

- In YA fantasy, tropes can be things like the Chosen One, Love Triangles, or Hidden Magic

- In middle grade, tropes can be the power of friendship, magical animals, magical academies

While not all books in these genres include all of these things, and while these things can certainly be cliche if you don't put your unique take on it, they are what readers enjoy about a genre. After all, isn't that why you read a certain genre, because there are tropes and elements within that you enjoy?

The way to use these stereotypes and tropes to your benefit is to use them as a framework, understanding how they operate and why readers enjoy them. Then, sprinkle your unique author magic on them. How you describe characters, the dynamic between two characters, how certain elements show up or are utilized, all these can be unique to you and your book. You're not looking to reinvent the wheel, but rather give it a new coat of paint, your coat of paint, so that you write the story you want while delivering a satisfying reader experience.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Invent an alien species

Of course, your characters don't need to be human. Octavia Butler’s Xenogensis series is an example of an invented non-human race. In the series’ first installment, Dawn, a human woman Lilith awakens alone in a prison cell, only to learn that she is one of the last survivors of the human race. She has been abducted by the Oankali, a humanoid but thoroughly alien three-gendered species covered in sensory tentacles. The differences between the humans and the Oankali, and the Oankali’s unusual biology and reproduction, form the driving force behind the novel’s plot.

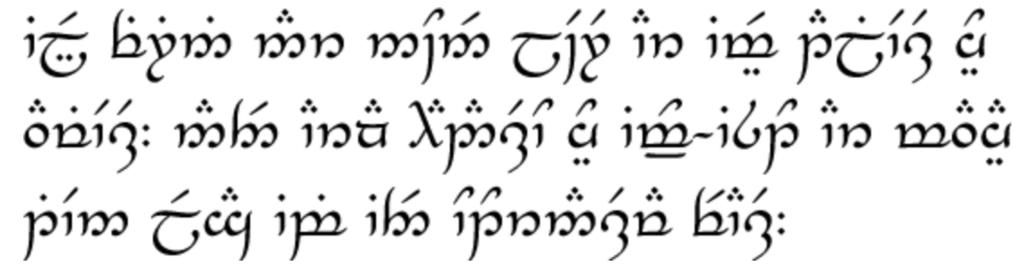

Come up with a new slang or language

When we talk about invented languages in fiction, most of us might imagine devotees of Tolkien whispering Elvish love poems — or Star Trek fans barking threats in Klingon. But language is something that applies to books across the board. Your decisions here will affect how the story develops and can make the difference in whether your book is believable.

Languages can be an interesting and exciting avenue of worldbuilding. The spoken word is a reflection of the cultures that spawned them, and the evolution of the language will often indicate some societal change.

For example, the youths in Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange speak a dialect called “Nadsat” which mixes Russian and English words. That choice alone implies a lot about the dystopian world of the book, suggesting a future where Soviet culture had spread further West.

Our worldbuilding guide will help you develop your ideas about language, but as a start, it's worth considering how many languages are spoken in your world, which language is most prevalent, and any common phrases or greetings which might come up a lot.

If your story is set on Earth, you can play with idioms and slang to create a unique dialect for your characters, that sets your fictional world apart from our own. Writers of historical fiction will also want to pay close attention to dialect, to ensure that any vocabulary being used is authentic.

So while language building isn’t essential, any little details like these that you can add to your worldbuilding will help create a richer and more immersive setting for your story.

4. Elaborate your civilization’s history

Civilizations are defined by their history. That might be a very broad statement — but it contains a kernel of truth. Writers should have a solid grasp on the history of their world, regardless of genre, and should be familiar with the key events that matter to the story they’re telling or the culture they’re exploring. So, how can you go about this?

Once again, a popular way to flesh out the history of your world is to borrow from our own. The line between historical fiction and fantasy is somewhat blurred, and with good reason. A good fantasy world will have a history that’s every bit as interesting as the one we have here on Earth Prime, so why not draw inspiration from it?

Q: Should I follow current trends or write the story I’m most passionate about?

Suggested answer

If you write a book inspired by 2025 trends you might find that by the time it's ready for submission and even publication the trend has moved on to something new. It takes a long time to write a book: you have a better chance of sustaining momentum and enthusiasm if you stick to your passion project. I rather believe that readers pick up on that passion too.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The issue with following current trends is that the trend may be over before you get your book completed and out to the world. If you write what you are passionate about, the story will usually end up being stronger because you are writing a story that means a lot to you, as opposed to writing something just because you think it might sell.

However, you want to be sure the story you are passionate about still has a strong possibility of selling by avoiding cliches and plots that have been overworked and overdone.

Strong stories that readers can relate to will have a good chance of finding an audience no matter the genre.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Going back to A Song of Ice and Fire, Martin famously patterned his book's central conflict after The War of the Roses. Using a veiled version of English history as his starting point, Martin then fills in the rest of his rich history with dragons, mad kings, and ice zombies. Similarly, RF Kuang’s The Poppy War is a fantastical reinterpretation of 20th-century China, and contains a fantasy drug-driven conflict inspired by the real-world Opium wars.

Speculate on history-altering moments

Let’s say you’re dealing with a futuristic version of our reality: there’s still plenty of work to be done. You need to have some idea of what’s happened between now and the time when you set your book. Start by speculating on developments in technology and society. Then, crucially, figure out how these changes have affected the characters and cultures in your book.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

If your book is an “alternate history,” it may stem from a single “what if” question. Think of a single point of divergence: a moment in history that shifted ever-so-slightly, leading to changes that ripple forward through time.

In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, the point of divergence comes with the assassination of President Franklin Roosevelt in the early 1930s. It results in a continuation of the Great Depression and American isolationism, allowing Germany and Japan to win World War II. The book then answers the question: “What would 1960s America be like if the Allies lost the war?”

5. Create systems of technology and magic

Perhaps the defining feature of any SFF book is its systems, whether they be magical or technological. It’s important to consider the details of how these things work carefully; just waving your hand and saying “and there’s magic” won’t cut it. You’ll have to define the magical or supernatural elements of your world.

With both science fiction and fantasy worldbuilding, you’re likely to come across the phrases “hard” and “soft” frequently. These labels are a (somewhat arbitrary, but still helpful) way of distinguishing between different types of SFF. Let’s take a look further, so you can decide where your world falls on the spectrum.

Spell out the rules of hard magic

A hard magic system is one defined by its rules, and which has clear and explicit boundaries on when said magic does and doesn’t work, and what the consequences of using magic are.

Q: What should I do if someone has already written a book with my idea?

Suggested answer

Write it anyway!

The market for books is huge and each writer's voice is unique. You will have a different way of presenting the informaiton or telling the story, even if it's similar to someone else's.

Alice is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Write a better book. There are many books written about the same topic, same ideas, same plots. You can't protect an idea, only the written expression of that idea. Go write your own book that is thoughtful, well-written, and thorough. A good book will find an audience.

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A great example of this type of magic system is Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series, set in a world where the primary form of magic is allomancy: a system whereby users swallow different metals, and metabolize them to different effects. Dedicated fans have been able to catalog all the possible variations of allomancy, and have discovered a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the actions of allomancers and their consequences, making for a true hard magic system.

As you can imagine, designing a hard magical system is a pretty significant undertaking that may involve a lot of variables. For that reason, it’s often worth dedicating a good chunk of your worldbuilding time to making sure your system is watertight.

Play with mystery and soft magic

You can choose not to explain how magic works and allow it to retain some of its mystery. After all, as soon as you explain all of magic’s secrets, it almost ceases to be magic.

One example of a “soft” magic system, one which doesn’t have hard and fast rules, is the one in Belgariad. The sorcerers in David Eddings’ Belgariad manifest their willpower through a system he calls ‘The Will and the Word’. It doesn’t require any potions or scrolls, and the so-called “rules” are able to be broken. As such, the limits to magical powers in this world are more conceptual than they are practical, and you’d be hard pressed to describe exactly what can and can’t be done.

While the flexibility of a soft magic system may be appealing — after all, you can’t break a rule if you haven’t established it — it certainly isn’t a get-out-of-jail free card. If you have an ‘anything goes’ approach to magic, your characters’ actions may cease to have consequences: you can bring anyone back from the dead, time can be reversed, your hero can escape from danger just by ‘magic.’ Be sparing with your use of soft magic, and don’t use it as a deus ex machina that miraculously solves your plot issues.

Explain how magic impacts the world

As well as defining the rules of your magic system, consider what it means to have magic. What are the consequences on both your world and the people using it? Maybe it takes a physical toll on the user, or perhaps there are emotional, mental, or social implications to exercising magic.

Who can use magic? If your protagonist is the only person with their gift, how does the world around them react to it? Are they revered or reviled for their abilities?

Q: What are the most common craft mistakes new authors make?

Suggested answer

One of the biggest mistakes I see from new authors is that they finish writing their manuscript and then they think they are done and ready for an editor to go through and review.

Writers need to be their own editors first. Because there are so many potential new authors every day, it's imperative that writers go back and edit their work thoroughly. That means reading, and rereading what they've written to understand how their characters develop through their novel, or how the topics that they brought up in chapter two are refined and built upon in chapter nine. Through that reading process, writers should be editing their work as they find pieces that aren't strong enough or need to be altered to make a better overall manuscript.

Matt is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The most common writing mistake I see from first-time authors is cramming too much into the first chapter. Your first chapter is a meet and greet, where you establish credibility, likability, and optimism that the book is worth the reader's time. Hook the reader, show your personality, but don't dump all your knowledge on them at the beginning of the book. Take them on an interesting, helpful journey,

Mike is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Conversely, what happens if someone who should have powers, doesn’t? For example, in Codex Alera by Jim Butcher, the people of Alera bond in childhood with one or more "furies" — elementals of air, water, fire, earth, wood, or metal. Everyone, save the protagonist Tavi who happens to be the crown prince of Alera. This lack of bond comes to have major consequences as noblemen around him begin to eye his ultra-powerful father’s throne.

If, as in Codex Alera, magic is widespread, how do people learn how to use it? Trudi Canavan’s Black Magician trilogy has a Magician’s Guild, where people work their way up through a structured hierarchy. Wizards in Harry Potter attend boarding school and end up with soul-crushing jobs in magical middle management. By imagining how magic would function practically in your world, your book will become all the more believable and relatable.

Now that we’ve discussed magical systems, it’s time to turn our attention to science…

Be precise if you use hard science

This is a brand of writing with a particular basis in technological fact. Best known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greatest pioneers in this field, whose fictional inventions bear close resemblance to everyday items in the 21st century.

One great contemporary example of the hard science is Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, a novel which explores a real-life phenomenon in orbital mechanics, and imagines a three-star system containing a single Earth-like planet which experiences extreme destruction as it passes between the three.

The important point is this: if you choose to write about technical science and technology, you should get your facts right. Many fans of the genre will likely know more about science than you do. If you get the details wrong, they will call you out on it; take, for example, Larry Niven, who was mercilessly teased by readers for having a character in Ringworld teleport eastward around the Earth to extend his birthday, when doing so would have actually shortened it.

You can always seek advice: the internet is a wellspring of information. If you’re shy about contacting people, Wikipedia is not a terrible place to start your research.

..or give yourself some slack with soft science

We know what you may be thinking — “Dammit, Reedsy, I’m a writer not a physicist!” If you’re not exactly science-minded but still want to write in the genre, you can always take the lead from writers like the late Iain M. Banks. His beloved science fiction novels are about The Culture, a post-scarcity society where all work is automated, and the citizens leave all the big decisions to a benevolent A.I.

Banks’ universe is full of science fiction tropes like droids and spaceships — but he doesn’t really explain how any of it works. It makes perfect sense from a storytelling point of view: novels set in the modern day rarely explain how iPads work. To us, they’re simply a function of everyday living. Banks makes a conscious decision to focus on character and story and he proves that you don’t need to know much science to write great science fiction.

Whether you go hard or soft, it’s important to establish your system ahead of time, so that you can remain consistent and logical throughout your work. Knowing how involved you want your systems to be will also mean you can plan how and when to deploy your exposition to maximum effect.

6. Distribute resources with a working economy

It may not sound too exciting, but considering something as fundamental as the economics of your world can be extremely helpful in making it a believable one. This isn't essential, but having an understanding of the economy can help you imagine how your characters will move through the world.

Take, for example, Anne McCaffrey’s iconic fantasy series, Pern. While the dragons are probably what most readers come away remembering, those who play close attention to the mechanics of the world are rewarded with a fascinating system to wrap their heads around. In Pern, the wooden tokens (“marks”) used for trade hold no intrinsic value – they don’t correspond to, for instance, a measure of precious metal, but are simply worth what they are traded for. So, your mark may be more or less valuable, depending on simply how well you are able to haggle to trade it.

Your economy may also be a speculative one, like the post-scarcity economy in Iain Banks’ Culture series. The series explores the implications of a world where most goods can be produced abundantly with minimal or no human labor, something Banks describes as “space socialism”.

As a minimum, it’s good to consider what the main valuables are in your world, how trade takes place (is it a barter system? Do people trade with money?), what the currency is called if there is one, and where your heroes come in the financial pecking order.

7. Determine your world’s power structure

As well as creating the history and economy of your world, you may also want to consider other institutions and power structures, such as religions, governments, or political ideologies. Again, this might be drawn from reality: Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series features a society dominated by the Magisterium, a religious body modeled in part on the real-world Catholic church.

You might also want to borrow from the past, like the feudal system of Dune, or extrapolate into the future, like the theocratic, totalitarian state of Gilead in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that stories set in other worlds have always actually been about the world we live in. Some of the most enduring works of science fiction and fantasy are profound commentaries on human culture and, in particular, our relationship to power and powerlessness. So even if your story takes place in a galaxy far far away, always remember to ask yourself what are you trying to say about society or the human condition and try your best to be intentional with how you use real-life source materials.

And with that final point, it’s now over to you: remember to download our free worldbuilding guide for tips on how to create your own fantastic lands and customs. We can’t wait to see your brave new world. Qapla'!*

*Klingon for “good luck”