Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

10 Personal Narrative Examples to Inspire Your Writing

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Personal narratives are short pieces of creative nonfiction that recount a story from someone’s own experiences. They can be a memoir, a thinkpiece, or even a polemic — so long as the piece is grounded in the writer's beliefs and experiences, it can be considered a personal narrative.

Despite the nonfiction element, there’s no single way to approach this topic, and you can be as creative as you would be writing fiction. To inspire your writing and reveal the sheer diversity of this type of essay, here are ten great examples personal narratives from recent years:

1. “Only Disconnect” by Gary Shteyngart

Personal narratives don’t have to be long to be effective, as this thousand-word gem from the NYT book review proves. Published in 2010, just as smartphones were becoming a ubiquitous part of modern life, this piece echoes many of our fears surrounding technology and how it often distances us from reality.

Q: What do agents and publishers look for in memoirs written by non-famous authors?

Suggested answer

When I vet memoir submissions, I'm looking for writers who pay close attention to scene-building. When did this event occur? Who was there? What are some accompanying sensory details? On the flipside, sometimes memoirs don't succeed because information is presented without being tethered to a scene or a narrative. If you're writing about your life as an amateur foosball player, that could be a compelling memoir! But it's a tough pill to swallow when readers encounter 10 pages of foosball history if there isn't an occasion for that material. Better, I think, to spin a yarn, then insert enriching backstory material insofar as the narrative-- and the scene-- requires it.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

"Memoir is difficult." "Memoir is a hard market." "Publishers aren't buying memoir." You don't have to dig far to find these discussions in publishing spaces because, as in every genre, agents and publishers can only take on books that they think they can sell. So a memoir by a non-famous author needs to have a powerful and unusual story to tell and/or to tell a story that is common to many people in an effective way. There's an element of luck, too – the memoir you've worked on for years may just happen to chime with something that's happening in the zeitgeist.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Two words: strong brand. But what is a strong brand? It can mean many things for a non-famous author, including a large platform. Yes publishers and agents will skip through a book proposal to see how many followers the author has on social media. But other factors can tilt the scales in your direction. Do you have famous connections? Would the book be endorsed, or a foreword written by, a famous person. Bottom line, authors must overcome the obstacle of relative obscurity with solid reasons what an agent or publisher should take on the book.

Mike is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Authenticity, personality, and a strong voice that can tell you a story that has something to teach us all

Bev is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In this narrative, Shteyngart navigates Manhattan using his new iPhone—or more accurately, is led by his iPhone, completely oblivious to the world around him. He’s completely lost to the magical happenstance of the city as he “follow[s] the arrow taco-ward”. But once he leaves for the country, and abandons the convenience of a cell phone connection, the real world comes rushing back in and he remembers what he’s been missing out on.

The downfalls of technology is hardly a new topic, but Shteyngart’s story remains evergreen because of how our culture has only spiraled further down the rabbit hole of technology addiction in the intervening years.

What can you learn from this piece?

Just because a piece of writing is technically nonfiction, that doesn’t mean that the narrative needs to be literal. Shteyngart imagines a Manhattan that physically changes around him when he’s using his iPhone, becoming an almost unrecognizable world. From this, we can see how a certain amount of dramatization can increase the impact of your message—even if that wasn’t exactly the way something happened.

Work with a creative nonfiction editor

Joe P.

Available to hire

Fast. Friendly. Experienced. Thorough. I'm here to help you be your best. Sample edits available.

Sally A.

Available to hire

Agent-turned-publisher with decades of experience--mainly in children's lit. Experienced with the general market and the Christian market.

Taylor M.

Available to hire

Over twenty years of experience as both a writer and editor specializing in middle grade and young adult literature.

2. “Why I Hate Mother's Day” by Anne Lamott

The author of the classic writing text Bird by Bird digs into her views on motherhood in this piece from Salon. At once a personal narrative and a cultural commentary, Lamott explores the harmful effects that Mother’s Day may have on society—how its blind reverence to the concept of motherhood erases women’s agency and freedom to be flawed human beings.

Lamott points out that not all mothers are good, not everyone has a living mother to celebrate, and some mothers have lost their children, so have no one to celebrate with them. More importantly, she notes how this Hallmark holiday erases all the people who helped raise a woman, a long chain of mothers and fathers, friends and found family, who enable her to become a mother. While it isn’t anchored to a single story or event (like many classic personal narratives), Lamott’s exploration of her opinions creates a story about a culture that puts mothers on an impossible pedestal.

Q: What advice do you have for first-time memoir writers?

Suggested answer

Can you ID one facet of your life that reflects a broader societal issue? If so, utilize that to transform your personal tale -- which might only interest a narrow demographic -- into a book with wider marketing appeal. (My fellow journalists call it a "news peg.") I handled Developmental Editing for a TV sports producer who achieved success in many aspects of the industry. But I urged him to use his memoir's subtitle to spotlight his experience with gender-equity issues. This helped push his book to being an Amazon #1 national bestseller. So milk your subtitle for all it's worth.

Joseph is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Listen carefully and ask all the questions that you think the eventual readers would ask.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In writing your memoir, my best advice for first steps is to zoom out and look at the end result as a "product." That's tough to do, especially with your life story. But if you start with a blank screen, the writing/drafting process can become overwhelming. Instead, create an outline that shows the chapters, and what stories/takeaways you want to share, and in what order. Don't do any "writing" at this stage, take on the role of architect, and develop a detailed plan for your book. When new ideas come, and they will, simply place them in the appropriate chapter for later expansion. Bonus tip: Use your voice recorder on your phone to talk out your book, then transcribe with free tools.

Michael is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

1) Memoir is a story and needs a plot and an arc just as any story does. The main character—in this case, you—needs to go through some sort of transformation, preferably some kind of growth or process of discovery.

2) Choose a theme rather than trying to tell your whole life story. You might begin by sketching out everything you can remember, and in the process you will likely discover some themes that pop up. Choose a theme that is clearly something universal or that a certain audience is sure to receive value from or find compelling, then find those stories that relate to the theme.

3) Remember that images, actions, and scenes communicate much more than explanations. Thus we have the age-old writing adage: "Show more than tell." Take the audience into those vivid moments with you; try to remember the lighting, the temperature, your sensations, and paint a picture of what it was like. If you can't remember certain details, imagine yourself back there and fill in those details that convey your feelings, the relationships, the environment, etc.

Clelia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

My advice to first-time memoir writers is to go in with your eyes wide open.

As a ghostwriter, I’ve learned that you need an ego that can handle being invisible. You may receive no credit whatsoever for the book beyond your payment—no mention on the cover, in the acknowledgements, or at the launch.

You are, after all, called a ghost for a reason: you’re ethereal, fleeting, and sometimes it feels like you don’t exist at all.

On the subject of payment, never agree to take it as a proportion of sales. Politely say “no thank you” and agree a fee for the work itself. A memoir can take 4–6 months (or longer) to complete, and you simply can’t afford to invest that much time without a guaranteed income.

You should also be prepared for the demands of the process. Some clients will call regularly-often in the evenings or at weekends.

They’ll want you on hand, they’ll set ambitious deadlines, and they’ll make what can feel like unreasonable demands on your time.

They may even get on your nerves!

But this is all part of the territory.

If you can accept the invisibility, the intensity, and the unpredictability, then ghostwriting memoirs is one of the best niches you can work in as a writer.

Helping someone tell their life story is a privilege, and despite the challenges, I thoroughly and unequivocally recommend it.

Edward is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What can you learn from this piece?

In a personal narrative essay, lived experience can be almost as valid as peer-reviewed research—so long as you avoid making unfounded assumptions. While some might point out that this is merely an opinion piece, Lamott cannily starts the essay by grounding it in the personal, revealing how she did not raise her son to celebrate Mother’s Day. This detail, however small, invites the reader into her private life and frames this essay as a story about her—and not just an exercise in being contrary.

3. “The Crane Wife” by CJ Hauser

Days after breaking off her engagement with her fiance, CJ Hauser joins a scientific expedition on the Texas coast researching whooping cranes. In this new environment, she reflects on the toxic relationship she left and how she found herself in this situation. She pulls together many seemingly disparate threads, using the expedition and the Japanese myth of the crane wife as a metaphor for her struggles.

Hauser’s interactions with the other volunteer researchers expand the scope of the narrative from her own mind, reminding her of the compassion she lacked in her relationship. In her attempts to make herself smaller, less needy, to please her fiance, she lost sight of herself and almost signed up to live someone else’s life, but among the whooping cranes of Texas, she takes the first step in reconnecting with herself.

What can you learn from this piece?

With short personal narratives, there isn’t as much room to develop characters as you might have in a memoir so the details you do provide need to be clear and specific. Each of the volunteer researchers on Hauser’s expedition are distinct and recognizable though Hauser is economical in her descriptions.

For example, Hauser describes one researcher as “an eighty-four-year-old bachelor from Minnesota. He could not do most of the physical activities required by the trip, but had been on ninety-five Earthwatch expeditions, including this one once before. Warren liked birds okay. What Warren really loved was cocktail hour.”

In a few sentences, we get a clear picture of Warren's fun-loving, gregarious personality and how he fits in with the rest of the group.

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

4. “The Trash Heap Has Spoken” by Carmen Maria Machado

The films and TV shows of the 80s and 90s—cultural touchstones that practically raised a generation—hardly ever featured larger women on screen. And if they did, it was either as a villain or a literal trash heap. Carmen Maria Machado grew up watching these cartoons, and the absence of fat women didn’t faze her. Not until puberty hit and she went from a skinny kid to a fuller-figured teen. Suddenly uncomfortable in her skin, she struggled to find any positive representation in her favorite media.

As she gets older and more comfortable in her own body, Machado finds inspiration in Marjory the Trash Heap from Fraggle Rock and Ursula, everyone’s favorite sea witch from The Little Mermaid—characters with endless power in the unapologetic ways they inhabit their bodies. As Machado considers her own body through the years, it’s these characters she returns to as she faces society’s unkind, dismissive attitudes towards fat women.

Q: What research should memoir writers conduct to ensure accuracy and depth before starting their first draft?

Suggested answer

When it comes to memoir, I think the most important thing to remember is, as obvious as it might sound, that the life of my client is the primary source.

That said, everyone's memory is slippery-we recall moments through the filter of emotion, later experience, and even family stories that may have become wildly embellished over the years. So, before I start drafting, I like to ground myself in two kinds of research: personal verification and contextual enrichment.

On the personal side, that might mean digging out old diaries, letters, emails, or even photographs. These aren’t just memory prompts; they help pin down details like dates, places, and the texture of a moment.

Talking to family or friends who shared an experience can also provide perspective. Sometimes they’ll remember things differently, which doesn’t have to undermine your story but can add depth and nuance.

On the contextual side, I’ll often research what was happening more widely at the time. What music was playing on the radio? What political or social events were unfolding in the background? Even small things, the price of a bus ticket, the football results that weekend, can enrich a scene and anchor it in time as well as act as a wonderful prompt or reminder.

In short, memoir research is less about becoming an 'archivist' of someones life (which makes it seem very technical anyway, which is not what you want at all) and more about giving yourself the tools to write with honesty, clarity, and texture. The aim isn’t to eliminate subjectivity (memoir thrives on it), but to make sure the shared recollections are as vivid and trustworthy as they can be-you will, with this in mind, notice what might best be called a 'disclaimer' in some memoirs which openly admit to how some stories may not be quite as they were at the time, else two or three characters known to the author have been combined into one.

As a ghostwriter, I carry out this same process alongside my clients: helping them test their memories against records, conversations, and cultural backdrops. That way, when we arrive at the first draft, we’re building not just on memory but on memory enriched — a story that feels authentic to the writer and alive to the reader.

Edward is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A memoir needs to be ghostwritten as the author themselves would write it, if they could. Further research shouldn't be necessary, unless there are facts that the author asks the ghost to confirm. If you start talking to other people you risk losing the author's own voice.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What can you learn from this piece?

Stories shape the world, even if they’re fictional. Some writers strive for realism, reflecting the world back on itself in all its ugliness, but Carmen Maria Machado makes a different point. There is power in being imaginative and writing the world as it could be, imagining something bigger, better, and more beautiful. So, write the story you want to see, change the narrative, look at it sideways, and show your readers how the world could look.

5. “Am I Disabled?” by Joanne Limburg

The titular question frames the narrative of Joanne Limburg’s essay as she considers the implications of disclosing her autism. What to some might seem a mundane occurrence—ticking ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘prefer not to say’ on a bureaucratic form—elicits both philosophical and practical questions for Limburg about what it means to be disabled and how disability is viewed by the majority of society.

Is the labor of disclosing her autism worth the insensitive questions she has to answer? What definition are people seeking, exactly? Will anyone believe her if she says yes? As she dissects the question of what disability is, she explores the very real personal effects this has on her life and those of other disabled people.

What can you learn from this piece?

Limburg’s essay is written in a style known as the hermit crab essay, when an author uses an existing document form to contain their story. You can format your writing as a recipe, a job application, a resume, an email, or a to-do list – the possibilities are as endless as your creativity. The format you choose is important, though. It should connect in some way to the story you’re telling and add something to the reader’s experience as well as your overall theme.

FREE RESOURCE

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

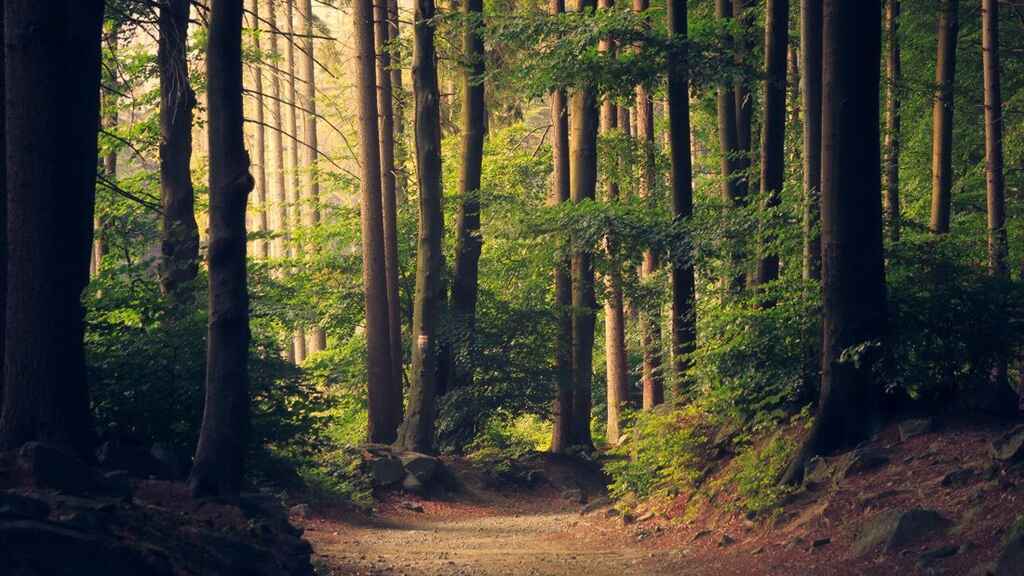

6. “Living Like Weasels” by Annie Dillard

While out on a walk in the woods behind her house, Annie Dillard encounters a wild weasel. In the short moment when they make eye contact, Dillard takes an imaginary journey through the weasel’s mind and wonders if the weasel’s approach to life is better than her own.

The weasel, as Dillard sees it, is a wild creature with jaws so powerful that when it clamps on to something, it won’t let go, even into death. Necessity drives it to be like this, and humanity, obsessed with choice, might think this kind of life is limiting, but the writer believes otherwise. The weasel’s necessity is the ultimate freedom, as long as you can find the right sort, the kind that will have you holding on for dear life and refusing to let go.

What can you learn from this piece?

Make yourself the National Geographic explorer of your backyard or neighborhood and see what you can learn about yourself from what you discover. Annie Dillard, queen of the natural personal essay, discovers a lot about herself and her beliefs when meeting a weasel.

What insight can you glean from a blade of grass, for example? Does it remind you that despite how similar people might be, we are all unique? Do the flights of migrating birds give you perspective on the changes in your own life? Nature is a potent and never-ending spring of inspiration if you only think to look.

FREE COURSE

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

7. “Love In Our Seventies” by Ellery Akers

“And sometimes, when I lift the gray hair at the back of your neck and kiss your shoulder, I think, This is it.”

In under 400 words, poet Ellery Akers captures the joy she has found in discovering romance as a 75-year-old. The language is romantic, but her imagery is far from saccharine as she describes their daily life and the various states in which they’ve seen each other: in their pajamas, after cataract surgeries, while meditating. In each singular moment, Akers sees something she loves, underscoring an oft-forgotten truth. Love is most potent in its smallest gestures.

Q: What types of nonfiction authors are likely to succeed without an agent, and why?

Suggested answer

If you are a celebrity or significant political figure and are really going to only write one book, you are probably better off having a lawyer who bills by the hour than an agent to whom you have to pay 10-15%. Examples of people who used a lawyer instead of an agent include President Bill Clinton, Nikki Haley, Karl Rove, Janet Yellin among others.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you have a large platform (like a big social media following, an influential organization, or an active speaking career), take a look at the world of hybrid publishing. Hybrid publishing allows you to bypass the agents and editors in the traditional publishing world, and gives you more control over your finished product.

Hybrid publishing can be expensive. It's worth the investment if the book is a tool in your tool belt, and a way to build more authority in a field in which you're already well-known. If you are confident that your platform can drive sales without a dedicated publisher marketing team, it can be a great option!

Kate is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What can you learn from this piece?

Personal narrative isn’t a defined genre with rigid rules, so your essay doesn’t have to be an essay. It can be a poem, as Akers’ is. The limitations of this form can lead to greater creativity as you’re trying to find a short yet evocative way to tell a story. It allows you to focus deeply on the emotions behind an idea and create an intimate connection with your reader.

8. “What a Black Woman Wishes Her Adoptive White Parents Knew” by Mariama Lockington

Mariama Lockington was adopted by her white parents in the early 80s, long before it was “trendy” for white people to adopt black children. Starting with a family photograph, the writer explores her complex feelings about her upbringing, the many ways her parents ignored her race for their own comfort, and how she came to feel like an outsider in her own home. In describing her childhood snapshots, she takes the reader from infancy to adulthood as she navigates trying to live as a black woman in a white family.

Lockington takes us on a journey through her life through a series of vignettes. These small, important moments serve as a framing device, intertwining to create a larger narrative about race, family, and belonging.

Q: What are some powerful non-celebrity memoirs, and what makes them stand out?

Suggested answer

I love, truly love, A Homemade Life, by Molly Wizenberg. She had an amazing blog for many years, and even won a James Beard Award for it, and this book was her (first) memoir about growing up with food but also her relationship with her parents and her childhood in general. She is an incredibly gifted writer, a genuinely interesting person, and A Homemade Life moved me incredibly.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

"Sold" by Zana Muhsen. I ghosted this about thirty years ago and people still contact me to say it is their favourite book ever. I think the secret was Zana's incredible honesty and authenticity - plus a powerful plot. "A Boy Called Hyppo" is another powerful story, ghosted for a boy who survived the Rwandan genocide. "The Boy Who Never Gave Up" is the memoir of a refugee from South Sudan who walked, as a boy, to South Africa.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What can you learn from this piece?

With this framing device, it’s easy to imagine Lockington poring over a photo album, each picture conjuring a different memory and infusing her story with equal parts sadness, regret, and nostalgia. You can create a similar effect by separating your narrative into different songs to create an album or episodes in a TV show. A unique structure can add an extra layer to your narrative and enhance the overall story.

9. “Drinking Chai to Savannah” by Anjali Enjeti

On a trip to Savannah with her friends, Anjali Enjeti is reminded of a racist incident she experienced as a teenager. The memory is prompted by her discomfort of traveling in Georgia as a South Asian woman and her friends’ seeming obliviousness to how others view them. As she recalls the tense and traumatic encounter she had in line at a Wendy’s and the worry she experiences in Savannah, Enjeti reflects on her understanding of otherness and race in America.

What can you learn from this piece?

Enjeti paints the scene in Wendy’s with a deft hand. Using descriptive language, she invokes the five senses to capture the stress and fear she felt when the men in line behind her were hurling racist sentiments.

She writes, “He moves closer. His shadow eclipses mine. His hot, tobacco-tinged breath seeps over the collar of my dress.” The strong, evocative language she uses brings the reader into the scene and has them experience the same anxiety she does, understanding why this incident deeply impacted her.

10. “Siri Tells A Joke” by Debra Gwartney

One day, Debra Gwartney asks Siri—her iPhone’s digital assistant—to tell her a joke. In reply, Siri recites a joke with a familiar setup about three men stuck on a desert island. When the punchline comes, Gwartney reacts not with laughter, but with a memory of her husband, who had died less than six months prior.

In a short period, Gwartney goes through a series of losses—first, her house and her husband’s writing archives to a wildfire, and only a month after, her husband. As she reflects on death and the grief of those left behind in the wake of it, she recounts the months leading up to her husband’s passing and the interminable stretch after as she tries to find a way to live without him even as she longs for him.

What can you learn from this piece?

A joke about three men on a deserted island seems like an odd setup for an essay about grief. However, Gwartney uses it to great effect, coming back to it later in the story and giving it greater meaning. By the end of her piece, she recontextualizes the joke, the original punchline suddenly becoming deeply sad. In taking something seemingly unrelated and calling back to it later, the essay’s message about grief and love becomes even more powerful.