Kristina Stanley

Combining her degree in computer mathematics with her success as a bestselling, award-winning author and fiction editor, Kristina Stanley is the creator and CEO of Fictionary — creative editing software for fiction writers and editors. Her novels include The Stone Mountain mystery series and Look the Other Way. She’s the story editing advisor to the Alliance of Independent Authors and on the board of directors for the Story Studio Writing Society.

A bit about Kristina

I have interviewed hundreds of editors worldwide about their process, and I’ve taken that information and used it as research into everything you're going to hear about today. I also ran a little test group where I had 13 professional editors edit the same manuscript simultaneously — but independently — to see how processes differ with the same story. On top of that, I teach story editors around the world, I teach people how to become a creative story editor, and I also edit. I edit one book a month to stay connected with writers and know that I’m providing what writers need.

Download the free resource Kristina mentions in this webinar. Click this link and scroll down to the “Download Story Editing Spreadsheet” button.

What is creative story editing?

It's basically a structural review and revision of your manuscript. It looks at characters, plot and settings, and the whole story. It's really hard — it’s the hardest form of editing a person has to do, whether it's an editor editing your story, or whether you're editing your own.

The reason it's so difficult is the editor has to keep in mind the entire structure as well as all of the details, and then figure out how they go together. It requires both artistry and technical knowledge of story — which is a hard thing to bring together. It takes a lot of practice and a lot of education. You have to be really dedicated to want to do it. Whether you're the editor or the writer editing your own story, it's a time-consuming, difficult task.

So as we go through this, please don't feel overwhelmed. I will give you some very detailed, specific steps that you can use to look at your own story.

Note: ‘story editing’ is also commonly called ‘structural editing’ or ‘developmental editing.’

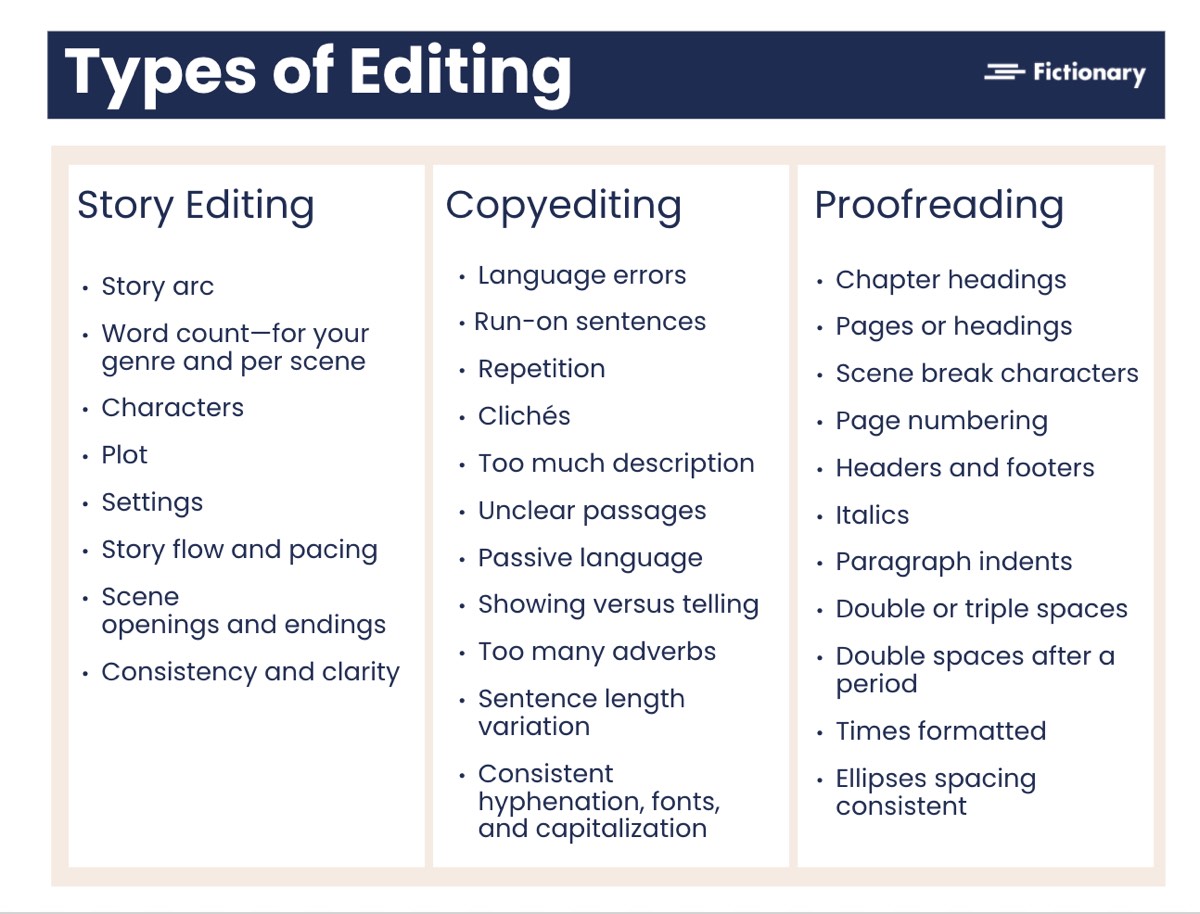

So before we get into the details, I wanted to talk a little bit about the different types of editing.

The three (main) types of editing

So story editing and copyediting can sometimes be done at the same time. Proofreading is not. It's a totally separate activity that requires completely different skills, but editors will go from one end of the spectrum to the other.

So you’ll start at the far left with story editing, that's the first step. You're not looking at any of the words, the paragraphs, sentence structure, et cetera.

Copyediting is the next level of detail. And it's starting to look at style. It's looking at the word level, sentence level, paragraph level.

Don’t copyedit too much in the story editing phase

I typically recommend that story editors focus hard on story editing and do minimal copyediting. It's been my experience that when an editor finishes, it takes the writer two to six months to perform the revisions. There's not much point in doing too much copyediting if the writer's going to revise, rewrite, and move scenes around. It ends up, in a sense, being wasted work.

I think the brain also works differently when you're editing a story versus when you're copyediting. You want your brain to focus on the actual story and not worry about the next level of detail.

Proofreading

Once the copyediting is done, there’s proofreading — which is really looking for typos. A proofreader should not be making sentence recommendation changes, or style changes, or story change recommendations. It's really about, “do you have extra spaces here?” and “are your chapter headings consistent?”

As a writer, when you're working with your different types of editors, you want to know you're getting the level of editing that you need for whatever stage your manuscript is in.

How do editors work?

An editor's process is going to vary just as much as a writer's process. If you talk to ten different writers, you’ll find ten different processes. Well, editors are the same.

These are the four areas that really vary between editors:

The tools they use

So everybody here knows I'm from Fictionary. So, of course, I edit in Fictionary StoryCoach. The other popular tools are MS Word because of their track changes. Google Docs, because people can work collaboratively.

I’ve interviewed editors who edit on paper. I interviewed a high-end editor in the U.S. who only edits verbally. She reads a paper copy and then has discussions with the writer. There’s a huge variance in the tools they use, which is fine because you want the editor to work where they're comfortable.

How they read

We had some editors who read an entire story, just read it as if it's a book, and that's it. Then they go back, and they start the edit. Then we had the next level, who’d read a scene, edit that scene, and then moved forward, and then do the structure at the end. Then there’s the other extreme: people who started editing right on the first sentence.

Again, it doesn't matter really how they're reading as long as they are reading in great detail. Editors have to read every word. When you have an editor, you want to make sure that they like your genre because you can't skim as an editor. That's a huge no-no.

Type of feedback

Some editors are very short and direct in their feedback, others are very verbose and explanatory. So there’s a full range.

Working with writers, the editor should be able to discern — from their first conversation at the beginning — what level that writer is at. Do they need an explanation of recommended changes or not? So some do, some don't, and the editor should be able to feel that out and figure out how much actual instruction they have to give, along with their editing.

Interaction with writers

Some editors work strictly in their software tool — and that's where all the information is. They sent it back to the writer, and that's the end of the relationship. On the other end, you might have a six-month coaching process where they're working scene by scene and chapter by chapter. But what every editor has in common is they all have to have the knowledge of what makes a powerful story.

How does an editor find story issues?

Editors need to know when something's not working. As an editor, that’s what I'm looking for — something that jumps out at me, and it doesn't feel right. But that's not very helpful to a writer: “it doesn't feel right.” There need to be specific reasons.

As soon as I start skimming the manuscript, I know I'm tired — I have to stop editing for a bit and go and do something else, like walk my dog and start again fresh. Or... it means the passage is particularly boring. And in which case, I have to figure out why it's boring.

I know something's not working if I'm confused about the story. Then there's clearly something wrong with it.

And I also know something's not working if I start reviewing the key story elements, find that they're missing, and I have to figure out why.

So on a second pass through, I examine all of the key story elements to look at a scene and try and figure out what suggestions I could make to the writer to help them make the scene better. Now, as a writer who’s editing yourself, you can do the same thing. So I'm going to show you how.

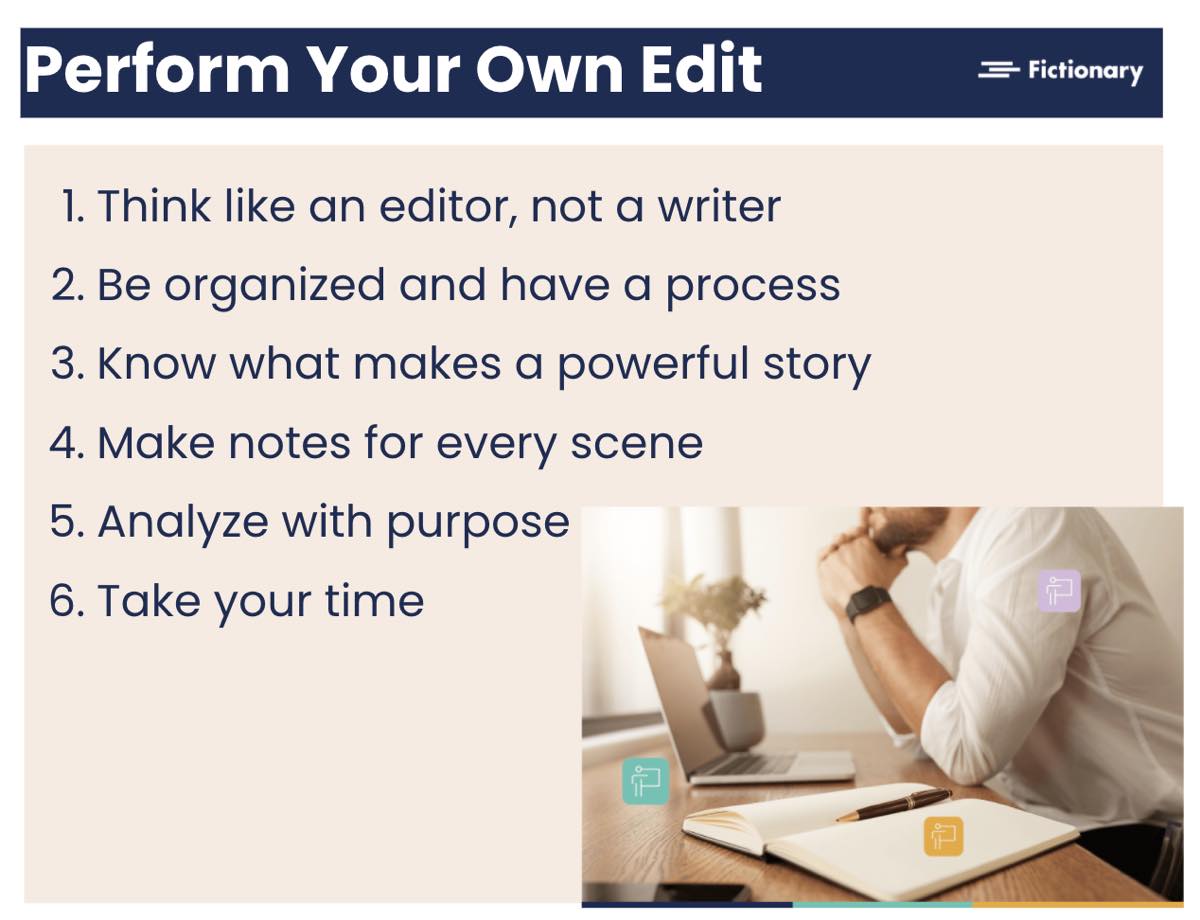

How to perform your own story edit

To perform your own edit, you need to think like an editor and not a writer. This is really hard to do because, of course, it's your story and you're emotionally connected to it. So you need to be organized and have a process that takes the subjectivity out of it. This way, you can make yourself be objective about your own story.

You also need to know what makes a powerful story.

When you're doing your own editing, make notes for every scene. Make notes about what you like, what's working, and make notes about what's missing or what you don't like. You don't necessarily have to change anything the first pass-through when you're reading, but you should look at things you're concerned about.

When I interview writers before an edit, they usually know what their strengths and weaknesses are. For example, somebody might say to me, "I'm not sure if my characters are likable." So that typically means they're not, but they don't know how to make them likable. So these are notes you can make to yourself while you're editing your story.

You need to analyze with purpose. So this is where you switch on your right brain, and figure out what you're looking at. You're no longer just reading your story; you’re looking for things that could be wrong.

And the last thing I want to say about this is you really need to take your time and not rush this step. A real revision can take two to six months, depending on if you have a day job and it's not the only thing you're doing. But usually, it's quite a bit of work. So take your time and really think about it.

The most common story issue

When I interviewed editors, I asked them what the most common story issue is. The answer was not the answer I was expecting, but it was consistent across the board. This really made me go away and figure out why writers are having this particular problem and how they might fix it. So here it is.

Knowing when to start and end a scene

Stories are written in scenes, and scenes go one after another, and they make up the whole flow of your story. By ‘scene’ I mean a section of your novel where a character or characters engage in action or dialogue. That's it. Nothing more. It's just, “something is happening.”

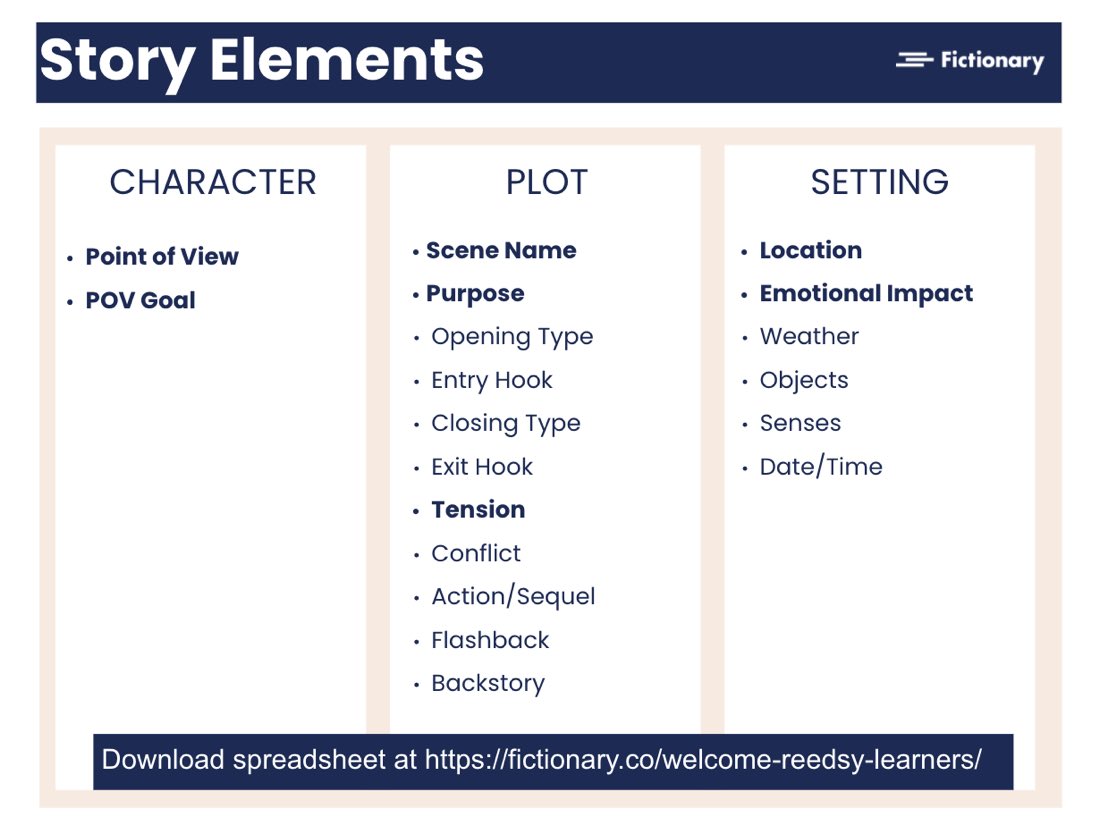

So every scene will have characters, plot, and setting.

A character doesn't necessarily mean a person. It can be an animal, it can be a storm. It can be any weird thing in a horror story, a fantasy story. It doesn't matter. It's whatever is driving that scene.

The plot is obviously what's happening, and the setting is where is that scene taking place.

If the structure of the scenes isn’t right, then it doesn't matter what the whole story is. It's not going to work. So a writer needs a way to figure out how to do that. And then from that, they can then make the rest of their story powerful. But without having the right scene structure, word count per scene, et cetera, it's tough to fix your story.

Starting a new scene

So before we get into analyzing our scenes, I want to talk about the importance of starting a new scene. When you're performing a story edit, the first action to go through is identifying each time you start a new scene. (Now, these are recommendations and you don't always have to do it.)

A new scene starts every time:

- the point of view character changes,

- the location changes, or

- there's a big change in time (a jump ahead, a flashback, etc).

I recommend starting at the beginning and marking down each new scene. This is the only thing you're going to edit for — this is what I meant by editing with purpose. Go through and you'll look at every place that the point of view character changes, the location changes, or the time changes, and put a scene break character there. Don't worry about the rest of this stuff.

You’ll want to see how it all breaks down. What do you end up for word count per scene? How do you want to theme your scenes? Do you want more than one scene in a chapter? This is going to set you up to give you bite-sized pieces from which you can analyze your story.

Action: Start at the beginning of your story and add scene breaks.

You can always go back and take out the scene breaks and make it one scene again if you don't like what it does. But it will force you to get to know your story in a bite-sized way.

The importance of the first scene

I want to talk about the first scene and the importance of it. So, the first scene has to do a lot of things:

- It needs to kick-off or set up the inciting incident. It doesn’t have to be the inciting incident. And the inciting incident is really just the first place that your protagonist's world gets shaken up a bit, and there's a change.

- You want to introduce the protagonist. And again, I want to stress, these are guidelines. So for example, if you read a prologue — and lots of books have prologues, particularly thrillers — where they're showing some other event that the protagonist is not in, the protagonist doesn't have to be in the first scene, but the protagonist needs to come in near the first scene. Don't leave it too long or the reader doesn't know who they're cheering for.

- Show a little bit of what the ordinary world is. It doesn't mean it can't be a full out action scene, conflict scene, whatever, but it has to give the reader an indication of what's about to change in the protagonist's life.

- There should be some kind of struggle. Whether it's an emotional struggle or a physical struggle, it doesn't matter.

- There needs to be dramatic tension. Dramatic tension is what hooks your reader and keeps them reading and will interest them in reading forward.

- It should foreshadow something. And you can look at the first scene after you've written your whole book and come back and see what you want to foreshadow. You don't really have to write it the first time through.

- And it should set the tone for your book. So if you're writing a book that's funny, there should be something funny in the first scene. If you're writing a thriller, there should be something thrilling so the reader knows what to expect, and they're not caught off guard when the tone shifts later.

First scene no-no’s

These are some of the most common mistakes that editors will find in an opening scene.

Too much backstory

This one I like to talk about. If you meet somebody new at a party and they go, "Hey, I'm Kristina. I was born in Ottawa, and I have three dogs,” and they just tell you their entire life story. You’d start to tune out. You're not very interested because really, does anybody care (except maybe my mom)? No. Probably not. So you want to limit the backstory and put in only what the reader needs to know.

The way to figure out whether you need the backstory: take it out and see if the reader still understands the scene.

Flashbacks

Another no-no because you're asking your reader to start over again. And you're asking them to do that before they've connected with the original characters in your scene. So it's a little bit dangerous to do, and it's better left till later in the story.

Description lists

By this, I mean anything you're describing in the book. If it's a person with brown hair and brown eyes and they're six feet tall, and you just list a whole bunch of attributes, the reader is automatically going to skim it. And if they're skimming in the first scene, they're probably not going to read past it.

Too much explaining

The next trouble spot is explaining too much: "John went to the bar because he really wanted to meet up with such-and-such a person," or whatever. It should be just, "John's at the bar," and you show what he's doing. And then the reader is immediately engaged.

Introducing every character

So if you can, your protagonist is in the first scene with minimal characters so that you give the reader a chance to get to know your protagonist and what's going on in their lives, before introducing the rest of the character cast and getting things a little bit confusing for the reader.

The last thing I want to say is don't spend too much time on the first scene. Get through your whole book, do all of your revisions, because all that will impact your first scene. So try not to make it perfect until you have your story set, until you're happy with your revisions. Then it's time to go back and you can look at what do I really need for a flashback, backstory, description, or foreshadowing. And you'll find, by the time you do your revisions, your first scene probably needs a bit of work anyway.

Evaluating Story Elements like an Editor Would

I love story elements. This is how I guide myself through editing my own work or somebody else's work. And this is how you can do it too: you can edit just like an editor would.

This is going to give you a way to be objective about your own writing. The story elements we're going to cover here are a subset of the ones I typically use [see the slide below]. You can also find them in the spreadsheet that goes with my Reedsy course on Story Editing.

Because we only have half an hour, I'm just going to cover a few of the most critical story elements — the ones in bold here.

Name each scene

Name your scenes in three words or less. This is one of the most critical things you can do in an edit. And it seems funny, but it ensures you know what the scene is about. And if you're an editor, it will ensure you know what your writer's scene is about. This is one of my books that an editor went through — they named the scenes to help them edit. Now, when you're doing it on your own, we'll get to it, but there are a few things that this is going to help you with.

By naming all of your scenes and listing them out, you have an after-draft outline, which might vary from your pre-draft outline. As you're revising and you're looking to move scenes around, or you want to find something quickly, you can look at the scene names and go, "If I move this scene, what other scenes will it affect?" And you can scan the draft and know the answer.

The next thing naming a scene does is to define the purpose of the scene, which I'll cover on the next slide. So at this point, everything is broken into scenes. And now go back to the beginning of your story and name each scene. And I don't mean put it in your book. You don't have to have scene names in your story. But you yourself need to know what scenes are named. So we're going to jump onto the purpose of the scenes.

Define the purpose of each scene

A scene name's will help you define the scene’s purpose. Why is this scene in your story?

It’s really easy to get excited, just write a great scene and then put it in your book. But maybe it doesn't belong in that story. Maybe it's not really related to the plot and it should come out of your book. (Don’t ever delete it, though —it might be in your next book, or you might use it for a short story or something.) But we all get carried away with our characters and you just kind of write something that’s great, but maybe not for this book.

So after you've named your scenes, ask yourself, "Why is this scene here?" And that's the purpose of the scene.

"Is it related to the overall plot?"

If the answer to that question is no, probably shouldn't be in the story. If the answer is yes, that's great, good to go. If the purpose is mild or weak, then what you want to do is see if you can beef up the purpose and add some things to it.

Make sure there are not too many purposes. You can confuse the reader by having too many different purposes in a scene. So here now you're going to have your list of scene names, and beside it, you're going to put the purpose of the scene.

And by this point, you’re starting to get a really objective view of your story because you're stepping back and analyzing it in a very organized way.

Action: Review each scene and list the purpose.

Choose the right Point of View characters

If you write one point of view for your whole story, that's great. You don't need to worry about this. But if you write from multiple points of view, it's very important to choose the best one for each scene. Once you know the purpose of the scene, it's easier for you to evaluate whether you have the right character.

So the point of view is really a promise to readers. A promise that they're going to experience the scene from the point of view of your character: through their eyes, their thoughts, their physical touch. This enables your reader to really get to know and connect with your character.

A quick note on head-hopping

I just want to touch on head-hopping and why it's not a good thing. Of course, you can do it. Lots of writers do it successfully, but it's hard.

What it usually does is jar your reader from the story. And the reader might all of a sudden not understand what's being described. Something’s out of place and then they have to think about it. And then they're not in your story anymore. For that reason, it can cause confusion.

To get rid of the confusion, then you need to add extra words to make sure the reader understands which thoughts are coming from which characters — you have to write around it. And because you're doing that, then you're slowing the pacing. And because you're slowing the pacing, then you're reducing the tension.

And so if you are going to head hop within a scene, then you need to take all of this into consideration and make sure it's worth doing.

How to evaluate POV

So everything is listed out: you've got your scene name, the purpose of the scene, you've chosen your point of view character. Now list those point of view characters for every scene in your story, and count them up. This gives you a way to figure out if your protagonist has the most scenes. And if not, why not? If they’re your protagonist and they should. So you need to decide if you have the right balance.

Action: List the POV characters for each scene.

If you write from, say, three points of view, do they have the right balance, based on their value into the story? If it’s more than that, could you bring it down? My rule of thumb is five to seven POV characters. Unless you write Game of Thrones, that’s a range that will let the readers identify with and connect with your characters.

POV Goal

The POV characters need to have a goal in each scene. And if they don't have a goal then really, what are they doing? They really need to be focused on accomplishing something:

- An external goal. In a murder mystery, for example, they want to solve a mystery.

- An internal goal. This is what they need, really, to have a happier, successful life. Something coming from within that they need in order to accomplish whatever they want in life

- A character goal has to be related to the plot. So it can't just be a goal to make money if that has nothing to do with the story that's being written.

- Consequences. If the character does not achieve their goal and nothing bad happens, it's not a very strong goal. So who cares if they make it or not?

Strong goals with consequences make a reader happy.

Sneaky things to check for

So here are the sneaky things to check for when it comes to POV:

- There's no goal. Look at the beginning of the scene and decide, does my character have a goal?

- There are too many goals. It's all over the place and the reader can't even remember them.

- A goal is inconsistent with the character's personality. If the goal for the scene is “I want more money,” and we’ve established that the character doesn't care about money, then that's an inconsistent goal and it makes no sense for the story.

- The goal has no consequences.

- The goal can be achieved too easily. If this is the case, there's no tension in the scene and the reader won’t really care about it.

Action: List the POV characters’ goals and review them against the criteria above.

Settings

This is the last criteria. So this has a massive impact on how your scenes and story play out. It's easy to just write and not think hard about where every scene takes place. But it can have a big difference.

If a place is important, you want to spend more time on describing it. And if it's less important to the story, it's just a quick, "We're in a pub," and that just happens to be the place. The reader will understand that it’s important to the plot if you're spending more time describing something. If you don’t spend that time, it's just a place where they are.

This is what a setting can do for you.

Highlight emotion. Does this setting have emotional impact on either the reader or the POV character for that scene? By that I mean, if you want the character to be afraid, put them in a setting that makes them afraid. Don't put them in their home with their family and everything's safe and happy and it's Christmas morning and we're all opening presents or something. They'll figure out pretty quickly.

You can change a lot of places. For my first novel, my husband said to me, "Do you know you start every scene in a door?" And I thought, yeah, I'm in an office all the time. So get out of the office. The scene might be in a workplace, but it's not very interesting for the story. And so I went through and looked for settings that would have an emotional impact.

Increase or decrease tension.

Set the mood.

Show characterization by how they're interacting with the setting.

Slow down or speed up pacing. You could have a nice romantic scene between a couple, but the setting could determine the pace. Are they sitting on a hill and there's a thunderstorm way off in the distance? That's romantic. A couple on a boat in the ocean? Not so romantic. So you can totally use the setting to slow down and speed up pacing.

Setting Issues

So here are the things to look for:

- Too much or too little description.

- Unclear where the scene takes place. Look at the beginning of the scene and make sure it's clear where a scene is taking place — unless the character themselves don't know where they are. And then it's fine that the reader doesn't know where they are.

- You want your description to be consistent with the point of view character.

- Be careful you don't use cliches. So a couple breaking up in a coffee shop or a restaurant, it's probably one that you don't want to use.

- Make sure they're not repetitive. It's okay if that location is really important to the story, but think about where things are and decide if you want it to be repetitive or not.

Action: Review each scene and ask yourself if it is the best place for impact.

Tension

Every scene must have tension.

The first thing to know is tension is the expectation that something bad is going to happen, where conflict is already happening. Tension really makes the reader want to read more, but only if the reader cares about the character. So you need to ensure that your reader is really cheering for or against your character.

The tension needs to be related to the plot. Something tense that has nothing to do with the story is going to fall flat, basically.

There needs to be variety of intensity. Not all scenes can be super tense that you can't stand it. The reader needs a bit of a break. So it needs to go up and down.

It needs to cause difficulty for the protagonist.

Action: Review each scene and check there is tension.

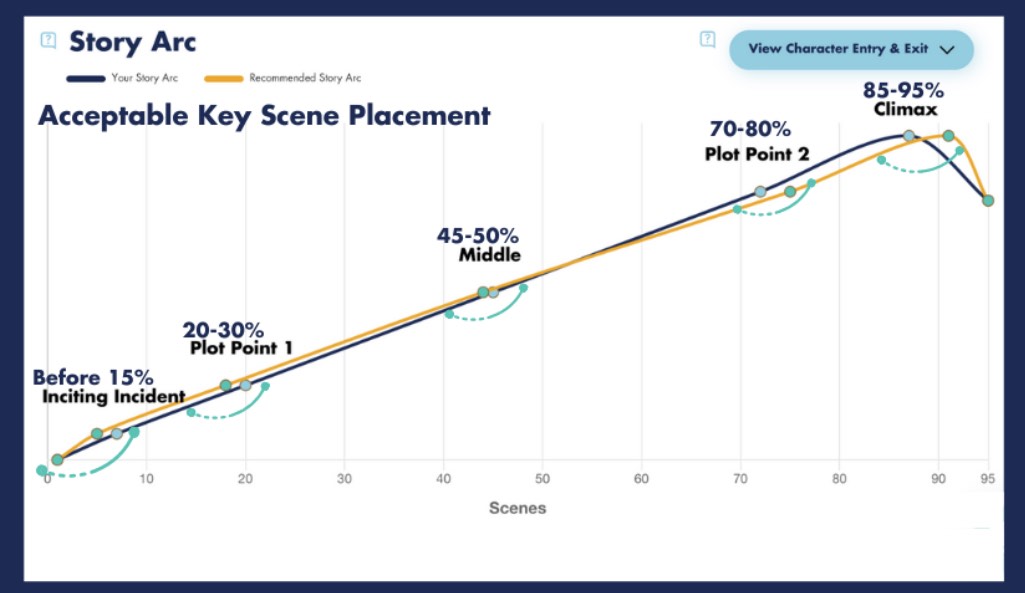

Story Arc

Once you've gone through all of this detail, come back and you want to look at your story arc. This is a story arc out of StoryTeller which has a recommended story arc. And then overlaid on it is the story arc for the actual book I was writing.

It’s important to know that there are five key scenes. And after you've done your revisions, you want to go back and find those key scenes:

The inciting incident. Within the first 15% of your book. If it's not, the reader just keeps waiting for something to happen: So what is this about? What is going on with this character? Find that scene where things change a little bit — taking your protagonist from their ordinary life to something different. That's probably your inciting incident.

Plot Point 1. This comes between 20 and 30%. If it's too close to the inciting incident, the story feels rushed. And if it's too far away, it feels slow. So this chart will help you with your pacing. Plot point 1 is the point of no return. So the classic example, Harry Potter arrives at Hogwarts. He gets off the train. He can't go back. There is no return to their original life.

The Midpoint. 45 to 55%. That’s where your protagonist starts being proactive instead of just reactive to what's going on in their lives.

Plot Point 2 comes between 70 and 80%. It's where they're at their absolute worst and life is horrible.

The Climax is between 85 and 95%.

So once you've done all of the pre-work that I've given you before this, go back and pick these scenes out of your story, figure out which ones they are, and where they fit on this story arc. Then you can assess whether you want to move your scenes around or not.

A few of my favorite editing books

I wanted to leave you with my favorite editing books. So I have no affiliation with these books, I don't make any money — these are just my favorites.

I have read, literally, hundreds of editing books. They help me with my creativity, and it’s where I often get ideas for my writing. They deepen my knowledge, so every time I'm writing or editing, I know more. They’ve helped me finish stories just by sparking my creativity.

These are all about story editing:

- Wired For Story by Lisa Cron

- On Editing by Helen Corner-Bryant and Kathryn Price

- Make a Scene by Jordan Rosenfeld

- The Artful Edit by Susan Bell

This about editing at the line level:

- The Anatomy of Prose by Sacha Black

Once you're past story editing onto the next level, it’s a really nice book to have.

50% discount on StoryTeller from Fictionary

We've got the StoryTeller app, which is for writers, and we call it creative editing software. And basically, it gives you a fast way of doing all of the things I've described in this webinar (and much more).

We have a free 14-day trial, and if you want 50% off just use the code REEDSY50 before September 20, 2020