This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

My name is Devin, and I'm here to talk to you about creating recommendable nonfiction. I'm the coauthor of The Workshop Survival Guide. I've also been tangentially involved in the creation of two other books — The Mum Test and Write Useful Books, which are both authored by my long time collaborator, Rob Fitzpatrick.

In the process, we happened across an interesting way to create our books that we believe has become pivotal to their success, which we call “useful books”. This is our shorthand for nonfiction that spreads through reader recommendation — it's not so much what you write about, but how you structure what you write about, which I think is a very liberating thing.

Before I dive into this whole idea, I want to get ahead of the fact that we built this structure for nonfiction books. That said, there are some aspects of this that we find are pretty useful for fiction, but we're by no means experts in creating a novel. A novel is a very artistic expression; it's something that comes from the soul, which is a very difficult thing to define, but when it comes to nonfiction, we find that this sort of thing is useful.

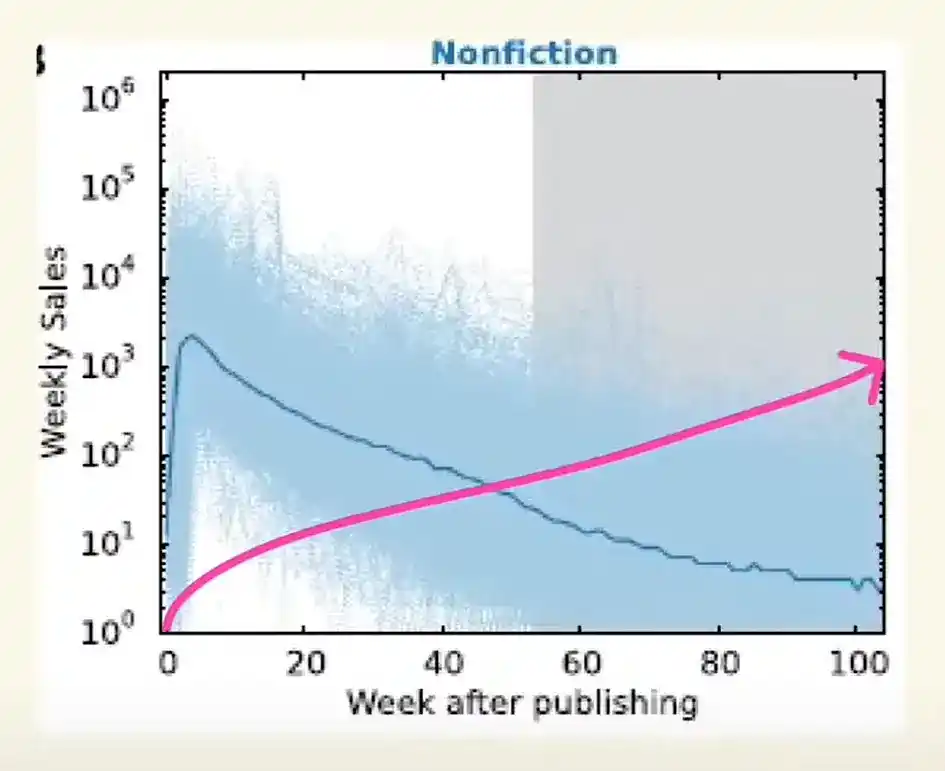

Launch spike vs. back catalog

While we were researching for Write Useful Books, we came across this extremely powerful graph. The bottom axis shows us the number of weeks since publishing, and the vertical axis shows us how many copies were sold.

If you're to believe this graph, there's a very obvious trend that it shows: the launch week is the make or break moment for your book. Whatever happens in that launch week, that is the apogee that you hit, and then it's all downhill from there.

That's a bit of a depressing idea for me, right? I spent all this creative effort creating this book, reviewing draft after draft — maybe I've even been writing in public so I've been building an audience. I’m trying all sorts of techniques to create a great book, and then it all comes down to how good my marketing is.

The little spike at the beginning — that's all based on the podcast book tours I did, the prelaunch publications I hit, the audience newsletter I built up, the one Reddit post that went viral, the BookTok thing that worked. It’s the culmination of all those little author-led marketing events, then almost every book after that peters off. Maybe you hit a viral post, or maybe you get a New York Times nod, and all of a sudden you get a bigger spike. But even the biggest spikes slowly decline.

“You’re always launching” is a popular piece of advice for authors, no matter what kind of book you’re writing. You might be sharing excerpts, or reauthoring it, or finding new channels of people who have never seen your book before. But at the end of the day, it's just sort of repeating the same thing over and over again: you get a little author spike and it declines.

Don’t get me wrong — those spikes are great! We don't want to not do this, but it's a bit futile if we’re aiming for a book that grows far beyond what our marketing skills are, right?

I'm terrible at marketing. It's not my forte. Every bit of marketing I have to do for a book requires an insane amount of work, and it feels very burdensome.

There’s a kind of book in this graph that is almost impossible to see, because so many other books plot the same path. They follow a path that looks more like the pink line: they have a very middling launch, often just showing up in the bookstore, or on Amazon, and they don't really make much noise when they release.

But then they start to sell a little bit more, then they sell a little bit more the next week, and by week 100, they're outselling what they sold in the first month. These books are called “back catalog books”, and they're a bit of an anomaly. They buck this “launch-or-die” trend where, even though they never really had this huge marketing engine that some of the big pop-science or autobiographies have, they keep selling somehow.

As they looked into this and started to figure out what was driving these anomalies, they realized that it was the readers — there was something very meaningful from that book that was easy to recommend to someone in a similar situation.

What we started to discover is that, while author-led marketing can create these beautiful short-term spikes (which are very valuable), there were some books with readers who adored the contents because it had a significant impact on them. That started to create this long term organic growth that wasn’t controlled by the author, agents, or publishers, but by the readers.

There was information in that book that was extremely useful, so when readers would encounter someone with a problem that the book addressed, they would think, “Ah, well, that person has that problem. I'm going to tell them how I solved it by reading this book.”

These evergreen recommendations are like a currency that grows a book far beyond the author's reach. It's what makes a normal book, not viral per se, but something that can continually grow over time.

So, it starts to become clear that we should try to optimize the writing process to make these evergreen recommendations happen. We shouldn’t optimize for marketing success, which is often the last couple of weeks before the book launch. Now we have this new goal in mind — we're no longer so worried about the launch week, but instead we’re interested in how we can create a book that is maximized for back catalog success.

Optimizing for back catalog success

There's a number of ways we can do this, but the basic framework that we lay out in Write Useful Books has three really simple steps.

First, a recommendable nonfiction book must serve a meaningful purpose in the reader's life. If it doesn't provide value or impact for them, why would they recommend it? When designing a book, start by considering your target audience — who am I talking to, and why am I talking to them? Where are they in their life at the moment that I want to speak to them?

Second, design for when the reader reaches for a book. They shouldn’t just be saying, “Oh, well, that's an interesting topic. I'm glad I'm aware of that.” The aim is to provide something that they can immediately apply to whatever situation they're in.

Third, you need to verify that all your info works — if you give someone advice and they try to use it, did it work? Did things get better for them thanks to your book? We need that feedback loop so that we can start to learn.

Rob and I wrote The Workshop Survival Guide to help a very specific group: professionals who have suddenly been tasked with running a workshop, despite having no prior experience. If you work in an office environment, you've likely encountered a situation where you have to give a big presentation or share an idea, but you're unsure how to structure it effectively.

That's who this book is written for. So when I recommend this book, I'm not recommending it because it was interesting — I'm recommending it because I know it can help someone in that exact situation. Ask yourself: is my book helping someone solve a problem? Is it helping them gain insight?

A useful book is more than just a how-to book. If you want a how-to book, you can just write a list of steps to follow. That's what a how-to book does. A useful book goes beyond that and makes for a beautiful reading experience that really affects the reader at that specific time.

Let me give you a concrete example. If there are any parents with young kids out there, you've probably been in the situation that I just went through. I recently had to teach my daughter to poop in a toilet. It's a pretty surreal experience if you haven't been through it. So, I started doing research — I asked friends, bought books, read blog posts, and watched YouTube videos.

For me, most parenting advice kind of falls into two buckets, and I hate both of them. The first is what I call the “prescriptive bucket” — that's when a book basically says, “Do these steps and you win.”

The problem I have with those books is that children don't follow steps. They're dynamic, agile creatures. No matter what sort of framework you set for them, they will buck that trend and it'll all go to pot. So I knew that those books would not work for potty training.

The second kind of parenting book bucket is what I call “overview books”. They’re these feel good books that give you the broad swaths of every possibility, but they never take a stand. They never give you the best-case scenario. I hate those books because you get to the end and think “Well, that was interesting. Now I know even less.” It's very, very frustrating.

Jamie Glowacki’s book Oh Crap Potty Training is brilliant for a number of reasons, but one of them is that it doesn't talk about what the kid needs to do. It's a story about how parents need to change their mindset about parenting and create an environment where their kids can succeed.

Yes, it is about potty training and yes, it does give some pretty prescriptive notes, but those prescriptive notes are wrapped in a narrative about creating a successful potty training experience for everyone involved — the parents, the carers, and the kid themselves.

It’s such a beautifully written book. You get through a couple of chapters, and you're feeling very confident in what to do. The book tells you, “Okay, you're at stage one, do these three things. Did you do those three things? If not, you're naughty. Go back to the beginning and start again.” It helps you catch yourself when you think things are going sideways.

Another example I love to give is this fantastic book by Christopher Voss, Never Split the Difference. In this book, Chris teaches you to negotiate effectively and gain the soft skills required to get people on your side to win a sale, but it's not presented as an academic text. It's presented as a memoir of his life as a cop, then as an FBI agent doing high stakes hostage negotiation, and then as a consultant, but throughout the book he's peppering you with tons of different techniques and how you can apply them to your life. It’s the sort of book we strive to write when we're thinking about a useful book — it’s useful and enjoyable.

Designing a useful book

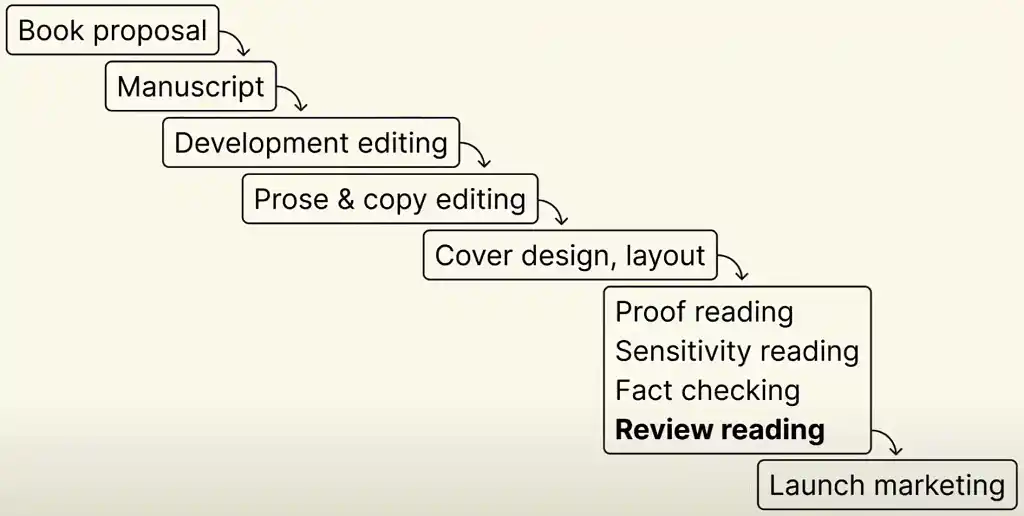

The useful book is basically a design choice we have to follow. To think about how to achieve what other useful book authors have achieved with their books, we have to think about how the writing process in general might be a bit backwards. This is our universal diagram of the book writing process:

It's sort of like a waterfall. Basically, you start off with your book proposal, and then you build your manuscript out. Then you get into the developmental editing, which is where you're really getting into major structural changes.

Once you get past developmental editing, the structure and content is locked in. After you’ve gone through prose and copy editing, you're basically done. Next, you do your cover layout and proofreading. Finally, at the very end of this massive process, you get to review reading. This is the first time that most of your readers will have actually touched your book.

You've made it through all the work of creating the book, and you're showing the reader for the first time ever at the end of this massive waterfall. You can probably see why this might seem like a bit of an odd choice, right? If we're writing a book for a reader to enjoy, why are they only picking it up when it's 95% done, and you can’t make any major changes? This is where the useful book design choice comes into play.

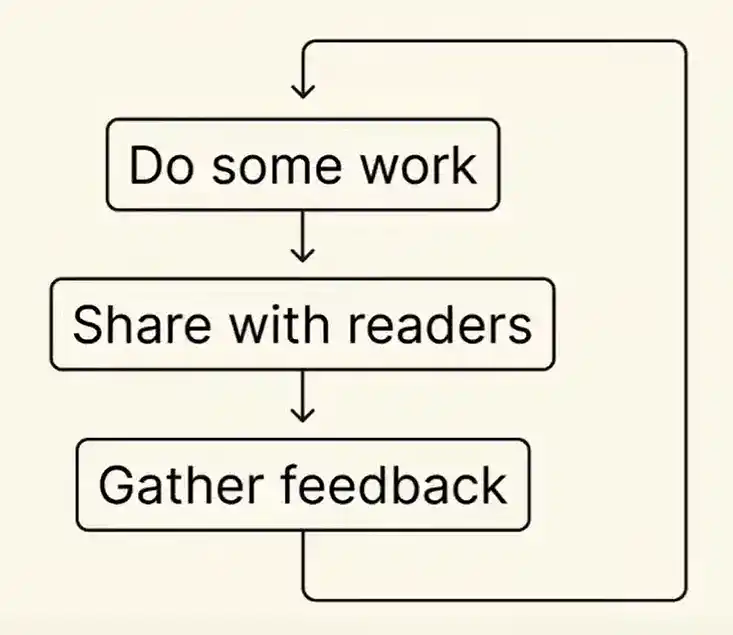

The basic idea we need to think about when building a useful book is as follows: if we get better feedback sooner, we're probably going to build a better book. That's it! That's the whole idea behind building a good, recommendable book.

If we go back to this diagram, you notice that all the creative work and research happens right between the proposal and development editing stages.

Everything below is effectively preparation for marketing, and we need to forget about that phase for now — we need to focus on just those first three stages. Instead of doing this very linear process of, “I have an idea, I'm going to spend a significant portion of my life writing it,” we need to flip it, so we're doing something more like this:

We need to do some work on our idea, share our progress with readers, get feedback on that progress in an effective way, then do more work. This is how we start to build a better feedback loop into our authorship process. So how do we do that?

It seems like it's pretty difficult, especially when we may not be confident that what we're writing about is even interesting. That's why we've got to get the readers involved from the get go. There's three ways that you can start doing this today.

First, become the book. Before you even pick up the pen to start writing prose, focus on sharing the content you're excited about with the reader in a meaningful way. This might involve coaching, consulting, or mentoring them.

The Workshop Survival Guide draws heavily from our experience building an education company, where we developed a unique approach to workshop design. When Rob and I realized, "Hey, there might be a book in this," we skipped the outline phase and instead wrote a few sample chapters to test the waters.

We reached out to a few friends and colleagues that we knew were in the space, and we offered to help them with it. We didn’t make their workshops for them, but we sat with them and watched them work, and sort of taught them our process.

We found two people very quickly, and within a couple of days, those two turned into five because they were recommending others to us, saying things like, "Oh, this other person I saw at an event — their workshop was terrible. You should go talk to them. I have their details." Before we even started writing the table of contents, we've started to shape our book.

The second thing that we recommend doing is beta reading. The number one thing I want you to take away from beta reading is to share what you're writing earlier. We recommend starting beta reading with chapter one, not draft one. If you get to draft one, you might’ve written 60,000 words — you've waited too long. What if there are fundamentally incorrect things?

You want to start your beta reading process painfully early. For Write Useful Books, we started by sharing a couple chapters. It was rough, but it taught us a lot about what readers did and didn’t find interesting.

After the first round, we had more confidence in what would be effective and not effective, so we went back to the writing room and started churning out more pages. When we did the next round of beta reading, the parts we’d edited went over a bit better, and we were getting more nuanced comments.

The final thing you need to do to really get this little loop into your authorship process is run followups. Check in with the people you're helping to see if it actually helps.

One of our community members is writing a book on hiking trail maintenance. He's a very experienced hiker and park ranger who often sees people performing poor trail maintenance. For his follow-ups, he visits trails that people are maintaining to evaluate whether his techniques are working and if his ideas are being properly understood. The key questions to ask are: What's working? What's not helpful? And who would they recommend for this process? Running those follow-ups is key.

How do you get started?

If you’re writing a non-fiction book, you may be thinking: how can I start? How do I take these big ideas and start doing them with my own prose? There's a couple of ways I'll suggest, and a lot of them can be done in a couple of minutes, if not hours.

The first thing we recommend is to run a book audit. A book audit is simple — it's sitting down and looking at the text you've written and counting how many pages it takes before a reader gets some value out of your book. You'd be surprised by how many business books I've read where the information was exceptionally interesting, but it took me a hundred pages to get to it.

That is a terrible reader experience. You make a promise to, say, teach me how to do better financial planning, but I have to slog through forty minutes of your backstory before I get to the first thing that tells me how to save money. The good news is, if you catch it now, it's easy to fix. Do that count, figure out where you're hiding the value, and how you can scoot that value closer to the front.

The other thing, like we’ve discussed, is beta reading. Don’t wait until version one — start with chapter one. We’ve even had some authors who started with a little abstract about what their book's going to be. The “writing in public" movement (which we love) encourages authors to blog about their ideas before they write them down, which is the same sort of idea. It’s kind of like beta reading in public.

Check that your promise is on the cover. One of the fun activities you can do if you're getting stuck with your book is designing the front matter; design the cover, the title page, and the subtitle to help work out how you want people to first interact with your idea. Do the title and subtitle tell you what the book is for? Does the book match that promise?