This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. To find out more about what Jeff can do for your story, head to his profile on Reedsy.

I've been in the entertainment industry — mostly movies and TV — since about 1986. But for the last 15 years, I've also been very involved with the publishing industry, not just as part of the self-publishing revolution, as they call it, but also traditional publishing. I'm a traditionally published author with my own self-publishing imprint, Storygeeks Press. A lot of what I've learned over the years (doing this for as long as I've been doing it) are that there are some real correlations now between long-form prose, which most of you are writing, and screenplay structure. I bring a lot of those skill sets to the table, especially television.

I've been at this for a long, long time and I teach through UCLA. I teach through Stanford University's School of Continuing Ed. I teach a course there with Caroline Leavitt, who I highly recommend. I've got a lot of teaching experience in the area of story structure, particularly.

I'm not a creative writing guy. I mean: I write, I'm a good writer, but my skill set lies in Story and we're going to talk a bit about that. Because what we're talking about today is a story problem, not a writing problem.

The problem we're going to discuss today is a very, very hard problem for a lot of writers.

What you'll get today

At the end of this [transcript], you're going to get three worksheets —because I don't want to just leave you hanging with all this information. Today, we're just scratching the surface of a very big topic, which is actually an entire chapter, chapter 12 in my latest book, Rapid Story Development: How to Use the Enneagram-Story Connection to Become a Master Storyteller. This little webinar we're doing today is based on that chapter where I go into all this in gory, gory detail.

I don't want to just throw all this information at you and just kind of leave you hanging, so I'm giving you some tools. You can go back and rewatch this webinar and then use the tools in conjunction with it, over and over and over again. You will end up with a process you can take away with you.

One of the hardest problems

This is an incredibly hard problem made even harder by the fact that it's not a writing problem, yet people approach it as a writing problem.

It's a story problem.

What do I mean by that? Story and writing are two completely different things. I'm going to pause there and let that settle in for a bit because this is very confusing to people. Storytelling does not need writers. Stories can be told in a lot of different ways and you don't have to be anywhere near a piece of paper and a pencil or a word processor. They can be danced. They can be mimed, like Marcel Marceau. They can be painted. They can be sculpted, they can be acted.

Stories need storytellers. They don't need writers.

Writing is a whole other animal, a whole different talent, a whole different skillset. A problematic story middle is a only a problem because people approach it as a writing problem that they can write themselves through. That's not how it works. It's a story development problem. Most writers are good writers.

Most of you are probably very good writers, but your storytelling skillset is probably on the weak side. That's not a judgment I'm trying to make about you. I'm just saying that's how it is. With the thousands of people I've worked with, almost everybody is weak on the craft of story development because that's not something that's taught in creative writing programs. You're just taught, write. "Writers write. Just go write. Don't edit. Don't stop yourself, just go. The first draft is always a piece of crap. Don't worry about it."

But you do need to worry about it because only people who have a really natural talent for story can get away with doing that. Ian McEwan or Stephen King can knock out a first draft in six weeks but do you think everybody should do that? Well, everybody shouldn't do that because they're not good at Story and they're going to get drowned in the story floodplain. That's why the middle is so critical: because it is a story development issue, not a writing problem.

The middle IS the story

The middle is your story. I mean: that's the story.

The first quarter and the last quarter, as important as they are, are beginnings and endings, right? Everyone's good with the beginning and everybody's good with the ending and then they go, "Now what the heck do I do?"

The middle is where all the action is. It's where we learn about who the protagonist really is as a character. It's where the whole adventure of the story is going to unfold beat by beat by beat, leading to that great ending you came up with. It's how we unfold all the subplots.

If you're writing a novel, you're going to need subplots. That's a whole other webinar by the way. You're going to have to write subplots and they all weave in and out. This is where readers end up loving or hating the characters in the book. It's the middle. That's why this is so hard. People don't develop their stories first and they think they can write through this problem, they find themselves snagged on all these issues. If you don't develop your story, you will not have a good middle so what will you have?

What is a "mushy" middle?

Let's define this thing you're going to end up with. What does "mushy" mean?

Episodic writing

This means your character faces a situation. They solve the problem, and it's over. The next problem, they come up against a new opponent, fight it out over something, win the day or not, problem over, next one; and you go through these little episodes through the middle.

How many of you can relate to that? It's like watching a tennis ball going back and forth. Your reader doesn't spend enough time in any one episode to really get invested. This also leaves you with disconnected subplots. You'll have all this episodic writing instead of one long throughline which you can only get by planning it out structurally. There's no clear structure.

Vague stakes and little/weak building tension

As a result of all this plan-free episodic writing, there are vague stakes and very weak or no building of dramatic tension or comedic tension. That's missing. There's no good cause-and-effect that's required good solid scene progression. This also adds to the episodic quality.

Passive protagonist

nd the worst of the worst of the worst is you end up with a passive protagonist, which we're going to talk about near the end. Active versus passive protagonists. Whenever you just jump into the writing of the middle and not really know what it is you're trying to do, you're going to end up with a character who's just getting thrown around by events rather than driving them dramatically. That's what a passive protagonist is.

If you don't solve these problems, you're going to lose your readers. And you're going to be so frustrated as a writer, you'll want to throw your manuscript out the window.

You don't want to get into the position after writing 200 to 300 pages of a novel and then going back to fix everything. Everybody does this. I call it backing into your story. You write hundreds of pages, then the wheels come off the cart and you go, "What the heck?!"

Everybody does the same thing. You start following the breadcrumbs backwards. Everybody, including me, ends up back at the beginning. It is the premise itself, the idea. That's where the story goes back first. The next place they go bad is at the middle.

How to avoid the mush

There's a whole lot more going on here than I'm going to talk about. But you just need to get your head wrapped around these two things:

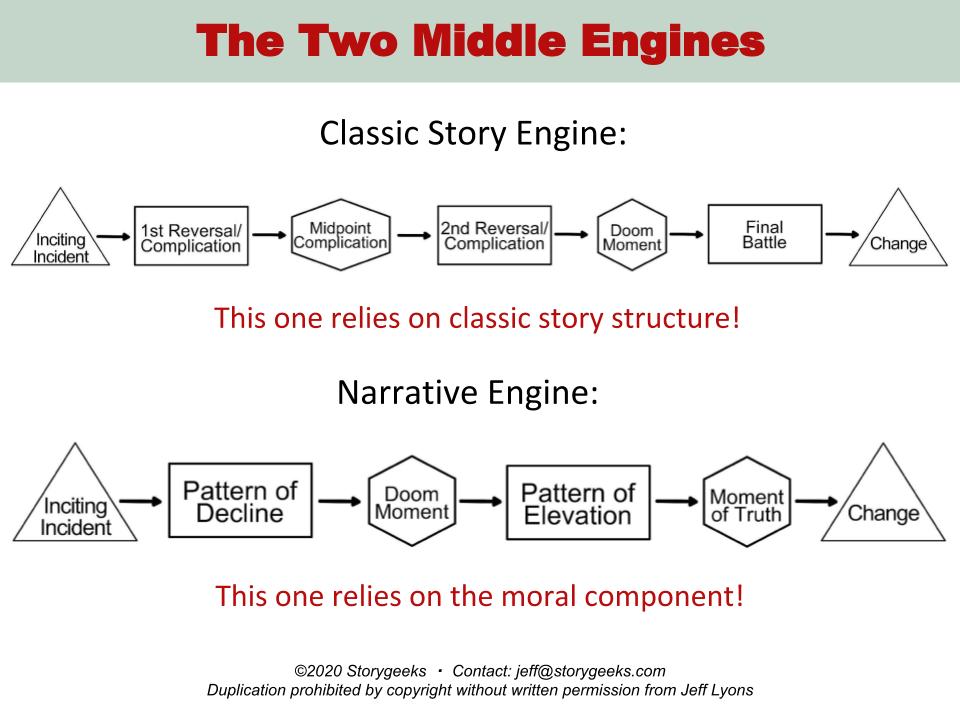

- The Classic Story Engine

- The Narrative Engine.

If your get your mind into a place where you're following these two engines, you can be assured (not guaranteed, there are no guarantees) that you will not have a mushy middle. It may not be great, but at least it's going to be structurally solid. You can go back and fix things much more easily than by winging it with a lot of guesswork.

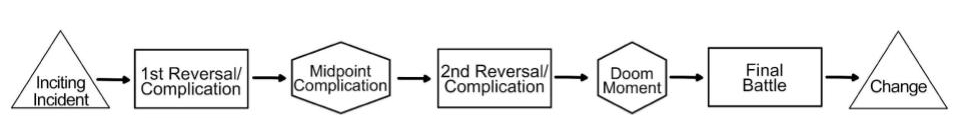

The Classic Story Engine

This relies on the classic principles of story structure. If you do not know Story Structure, go learn it. You can learn it from me (I've got a whole book on it, Anatomy of a Premise Line) or from anybody else you want. I don't care where you go, learn classic story structure.

What do I mean by classic? The story guru zoo is very crowded right now and very loud. There's a lot of noise out there, a lot of snake oil. Throw a stone, you're going to hit somebody teaching some process. What I have tried to do over the years is take the five or seven most common story structure pieces that everybody talks about — regardless of the proprietary language — and hammer that down into a workable idea of structure that is common to all stories.

Everybody who teaches this stuff is all teaching the same basic stuff. Then it gets all noisy and frantic because everybody's adding all their proprietary stuff on top of it just to confuse matters. This is just the nature of the beast. My motto is "listen to everyone." Try everything. Follow no one. You are your own guru. This is on you. This is your responsibility to learn this stuff. Nobody else is going to do it for you.

Inciting incident

Most of you are going to know what some of these things are, but a couple of them don't. The inciting incident is what kicks off your novel. It's the thing that happens that takes your protagonist from where they are in their life at the beginning of the book — usually in chapter three, chapter four at the latest. An event that happens and they go, "Huh. Okay, I've got to go over there now," and everything switches and now we're off to the races, okay? That's the inciting incident.

The inciting incident needs to be consistent with their character. We're going to talk about this a little bit when we get into moral component, but that's the beginning of your middle essentially; and then you have reversals, complications, which you've probably all heard about.

Reversals and complications

You need at least two or three of those where you set up an expectation and then you reverse the expectation. You know: the robber ends up being a good guy or some complication like that.

Midpoint

Two things need to happen at the midpoint:

- The community stakes need to rise, and

- The personal stakes of the protagonist need to rise.

What do I mean by that? I'm going to give you a silly example:

Bob and Mary are secret agents chasing the terrorists in lower Manhattan. Bob discovers that the terrorist has a bomb and it's going to go off in a subway station and it's going to kill hundreds of people. Then at the midpoint, he discovers, "Oh my gosh, it's not just a bomb. It's a dirty bomb and tens of thousands of people are going to be killed."

The community stakes have now risen. There's more danger, there's more jeopardy for everyone in the story.

And then at the same time, Bob also discovers that the terrorist is really his old buddy Ben from the Seals who's gone rogue. But he's also Mary's brother, and Ben is having a love affair with Mary. So if our hero kills Mary's brother, it could have put the love affair in jeopardy.

Now he's got a new problem. Not only is everybody going to die, but he could lose his lover. Both of these things happen very close to one another. The community stakes rise for everyone in the story, and a new threat rises for the protagonist.

That's your midpoint complication. Incredibly hard to do. Most people only get the first one. They don't ever link back or link forward to the character component where it creates more danger personally for the protagonist. If this is the only piece you ever accomplish in the middle of your story, you'll create more unity just with that one piece.

The Doom Moment

Then you have another complication down the line you want to come to before the doom moment.

Everyone intuitively knows about this moment.— if not, you'll learn this from any structure school. Sometimes it's called "a visit to death," the "all is lost" moment; every TV show, every movie, every book you've ever read has this moment. It's a critically important moment that you are writing towards.

A quick aside: Rather than thinking about just writing events, you're writing to these moments. You're trying to write to the story structure beats. Don't think in terms of acts. Acts are going to get you nowhere. I am not a proponent of three-act or five-act structure — or any act structure. Acts are really not useful. But what is useful is creating these points of structure in the middle and writing to those. That's what gives you a form and a foundation to work with.

The Doom Moment is where the protagonist looks like they've lost and the bad guy's going to win. But it's also the point where they realize, "Oh my God, I can't keep going the way I'm going. If I do, all will be lost. I will not get my goal. I will lose all my money. I will not get the girl. But worse, I'm not going to change. I've got to be a different person here. I can't do business as usual."

They don't know what that change looks like yet but they know they've got to do it differently now if they're going to get through this crucible. That's the beginning of their change. They haven't changed yet. That doesn't happen till the final battle. It's not just a "plot point" moment. It's a character moment where they have their first inkling of, "Oh my God, things have to be different. I've got to be different, but I don't know what that means, so I've got to figure it out."

That's the classic story structure middle that most people talk about. That's what most people have in their books when they write about this. That's what they talk about.

What they're missing, the secret sauce that's missing is the narrative engine piece.

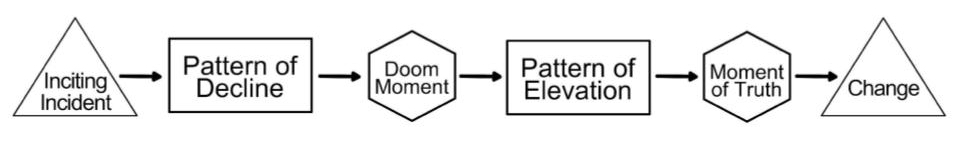

The Narrative Engine

This has the same inciting incident, weaving in and out of all these other structure moments we just discussed in a pattern of decline up until the doom moment.

This is something people don't think about, but I want you to really start thinking about it: as you're going through your story, your character has to be getting worse, not better.

Worse can mean many things. It just might mean that they're getting more emotionally distant or it means that they're killing babies. It could be any kind of degradation, but they are not acting in a moral way and they're in fear mode.

Then they come to that Doom Moment. They realize, "Oh my God, things have to be different. I have to be different." Then there's a pattern of elevation. They start climbing out of the emotional hole to come to the Moment of Truth where it's, "I have to change now. I know kind of what I have to do. I see who I've been. I see what I could be. What do I want to do?"

In The Godfather, Michael Corleone picked the bad side. He went on to the dark side and became the devil. You don't have to have a happy ending, but it is this narrative engine that's so critical.

The Moral Component

Let me talk about now what it is that's actually operating during this middle section. The thing that's driving all of this is this thing called The Moral Component. Caroline talks about it in her webinar on structuring your novel. She talks about the moral flaw. Everybody talks about the moral flow, but they don't tell you what the heck this thing is and how you can get one. It's made up of these three things:

- Moral blind spot

- Immoral effect

- Dynamic moral tension

We all have moral blind spots. They're behaviors that we carry out day to day that we don't see, but everybody else sees. These are blind spots. We're blind to it.

Immoral effect is how we're carrying that blind spot out in the world through behavior that's hurting other people. That's the immoral effect. The effect of our blind spot is we are acting not in a nice way in the world.

Dynamic moral tension is the story constantly giving the character an opportunity to change... but they always make the bad choice. "Okay, you've been being a real jerk here for 150 pages. You want to change now? Nope. Can't do that." They haven't changed yet. They haven't gotten to that doom moment, so they're going to make a choice out of that blind spot that's going to now create a new problem that will raise the stakes.

This is how you raise stakes in your stories: every time they make a new choice to do something, it creates more problems for them because they haven't figured out what's motivating them.

Example: The Verdict

Perfect example I'm going to go through real quick is The Verdict [the 1982 Paul Newman movie].

An ambulance-chasing lawyer outside of a funeral home takes a swig of a booze, goes inside, starts handing out his cards: "Sorry for your loss, sorry for your loss." They finally figure out this guy doesn't belong there and they kick them out. We immediately see how he's hurting other people. Okay, he's taking advantage of their pain. He's using them to get what value he can get out of them.

This is the same thing you do with the protagonist in your story. Once you know how they're acting badly in the world, what they're doing to hurt other people, you go, "What would that person have to believe about people in the world to justify acting that way?"

Frank in The Verdict sees people as worthless and or of little value, so he's preying on them. He's taking advantage of them because his worldview is, people don't really have a whole lot of worth.

Then you ask yourself about your protagonist, "What would they have to think about themselves to justify having that kind of worldview?"

Frank's taking advantage of people because people don't have any value. Guess what? Frank's a person too, so he doesn't have any value. He doesn't have any worth. Thus his self pity, his fall from grace, all the behaviours that he carries out in terms of hurting people in the world come from this fundamental belief about himself — that he has no value and doesn't have any worth and human dignity — which is wrong.

When you see the rest of the movie, that's exactly what's playing out. That's his blind spot. As long as he's operating from that point of view, every choice he makes to deal with problems will create new problems. It's not coming from the story, it's all coming from him. That's what an active protagonist is.

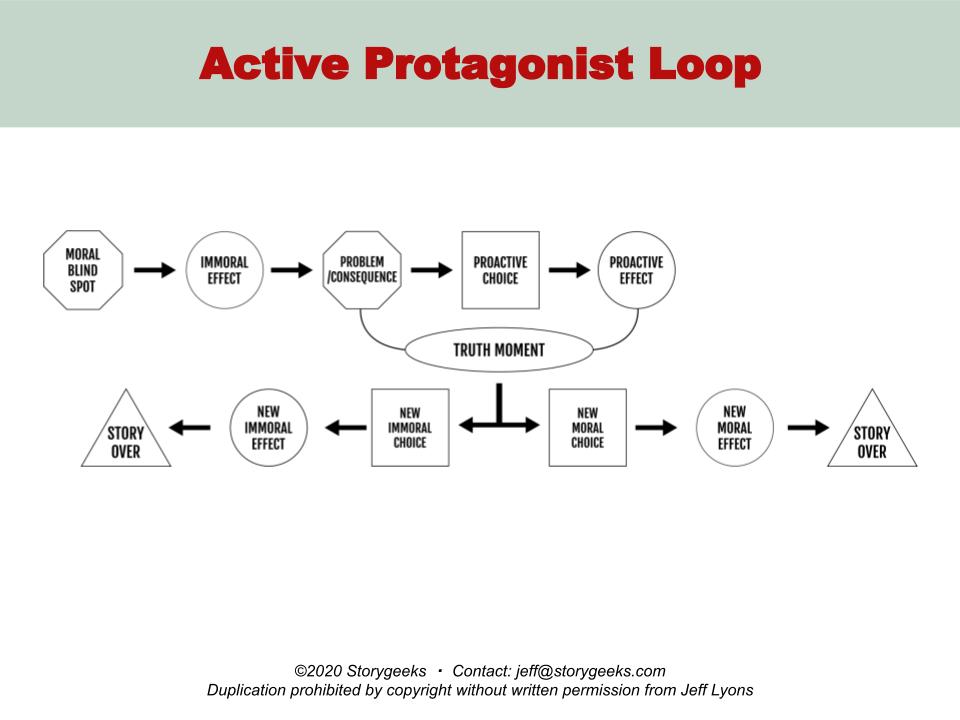

Active Protagonist Loop

Active protagonists have a blind spot. They're acting badly in the world — the immoral effect — and that action creates a problem that they have to solve. They proactively make a choice to deal with it, but it creates a new problem: what I call proactive effect.

"Okay, am I okay? No, I'm not. I'm going to go back and I'm going to make a new choice." This creates a new problem and boom, boom, boom. It's an engine that's constantly ratcheting up the drama for your character, all coming from the blind spot, from within the character. They're actively creating their own hell.

At some point, that truth moment, they go, "Okay, I can't do this anymore."

They change: a new immoral effect. But it's actually a moral one [going to the left in the diagram] and the story's over.

Or... they go in the opposite direction like Michael Corleone. "No, I'm going to go deeper into my blind spot because I cannot see the truth here and I'm terrified. I'm going to be getting even worse now." Story over.

But that's the engine I'm talking about. This character piece, this moral component, that is the narrative driver for the middle of every story. As long as your character is creating their own problems because of that moral blind spot, then they've got heal at the end and change, then you're going to have story beats in the other structure that are going to make dramatic sense and not just be stuff you're throwing in there because stuff has to happen: there's got to be a character basis for it.

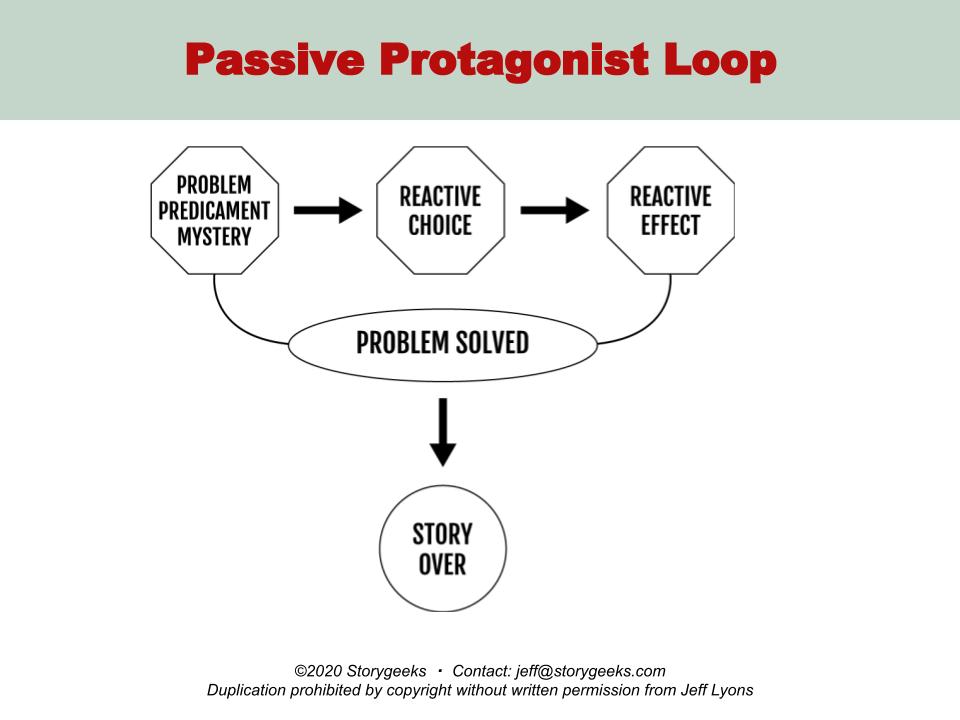

Passive Character Loop

This is what you have if you don't have an active protagonist:

- Problem predicament mystery.

- They make a choice. They do something.

- Is the problem solved? No?

- Next problem.

This character is a leaf on the wind, getting pushed by events and basically just solving problems. They're not generating the dramatic interaction. They're reacting to a world that is pushing and forcing them to be active. They're not the ones driving the action.

This is a situation, not a story. This is what most movies have. That doesn't mean they're bad or wrong: they're just not stories.

So often, middles fall apart because so many of the protagonists you write are passive characters. They're always coming up against problems, and then you get episodic, and then your middle has problems.

A quick note on short stories

It doesn't matter whether you're writing a 30-second TV commercial or Gone with the Wind or something that's 5,000 pages long, a story is a story. As long as they've got the components that make up a story, they will have these components in place. With short stories, you start as close to the end as you can, right? But you're going to have these same structures. There's going to be a desire line. There's going to be an opponent. There's going to be a dramatic question. There's going to be a growth moment... unless there isn't. Not every short story is a story story.

One of my favorite stories is "The Dead" by James Joyce and the ending is very quiet. It's the epiphany, the awareness of self that happens at the end. That's why short stories are so much fun because they're so compressed, but you can do all this stuff in a short story that you can't in a big novel. But in the novel, you've got the space. You can breathe. You can have subplots. You can have lots of characters. They're just so much fun for writers.

Summary and extra resources

The classic story structure engine will only be relevant, will only work well and be dramatically satisfying if you can add in that secret sauce: having them decline over the course of the middle and then elevate themselves after learning the lesson of their moral component. What are they going to learn about themselves at the end that is going to change them as a person? That is critical and that's what drives the character component of this across the middle.

I know this is a lot. I know it's crazy-making but you've got the tools now. So what can you do next?

1. Watch this video over and over again.

2. Fill in these worksheets to the best of your ability:

3. If you want to, you can buy my book and read chapter 12. It breaks all of this out in gory detail.

4. Download my free ebook: Rapid Story Development #5. It's a free ebook. It talks about all this moral component stuff in great detail.

Work with Jeff on your next book. Send him a request through his Reedsy Profile.