We shared Caroline's advice and nuggets of wisdom from this Reedsy Live session in a blog post titled How to Plot a Novel. Read it to find out what are her seven steps to outline a novel.

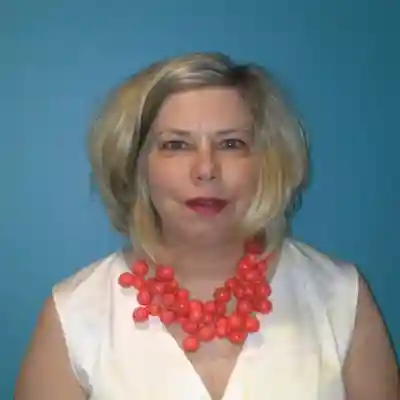

Caroline is an editor on Reedsy. To work with her on your next book, visit her profile and send her a request.