Blog •

Posted on Dec 15, 2023

Webinar — Generative AI, Copyright & Publishing

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →This is the transcript from our webinar on Generative AI on November 30th, 2023, led by Andrés Guadamuz: a Reader in Intellectual Property Law at University of Sussex. Andrés sheds light on AI and copyright in publishing, discussing questions about AI’s role in the creative industries, and discovering what the law says today, what it might say in the future, and how it affects publishing professionals. You can learn more about AI and copyright on Andrés’s blog.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Skip to 5:20 for the start of the webinar.

Introduction

Andrés: I’m a researcher in copyright and artificial intelligence who has been looking at this area for over 10 years. I started writing about text and data mining: obscure aspects of copyright. There were 30 people that read my first paper on the subject, but at some point it took off.

For the last couple of years, I've been extremely busy with people's interest in this. I am aware that there are people who are very anxious and have fears that artificial intelligence is going to take their jobs.

Q: What are your thoughts on AI advancements in the publishing industry?

Suggested answer

AI is here to stay, and the authors who learn to work with it will come out ahead. I know some people are worried it might replace creativity, but I see it as a tool—one that can make your work easier and more efficient. Whether it’s using AI to help edit a draft, brainstorm plot ideas, or analyze data for marketing, it’s all about working smarter, not harder.

Think of AI like a co-pilot. It won’t fly the plane for you, but it can help you stay on course and even discover shortcuts you didn’t know existed. The key is to embrace these tools and figure out how they fit into your process. Change is inevitable, and the authors who adapt will not only survive—they’ll thrive.

Jd is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I am happy to work with authors who have used generative AI as a tool towards getting their book closer to publication. I would like to know if this was used before I receive a sample and I trust the author has heavily edited the output to review the content and add their own distinct voice.

Alex is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I fall into that category too, as a researcher. However, I don't have the same experience that you have [as publishing professionals] and my perspective on this topic is going to be very practical.

AI generated picture published in New York Times

[Throughout this presentation] I'm going to be using a few images that I generated. Before, when I did my presentations, I used to get illustrations and images from Google. Now, I use my own imagination a little bit more. That’s why I’m using llamas: it’s part of my online personality. I've been told that I look like a llama, but most importantly, the llama has become the mascot of artificial intelligence.

Weirdly enough, I had an artificial intelligence image that I created, published in the New York Times. I never thought in my wildest dreams that it would ever get published in the New York Times, and you can probably see that there are a few wrong things with this image.

Copyright Law is National

In my experience, creators are well informed about copyright. You probably already know the basics, but sometimes, and this is not to disparage anyone, there are a lot of misconceptions or misinformation that seeps through. It happens that people get their information from other jurisdiction, for instance, but if you're in the UK, information from the US might not apply.

One very important thing that I want to stress is that copyright is national.

There are international treaties, but the law in your country may be very different, particularly copyright law, from what you sometimes find online. It's very important to keep this in mind because the law changes quite a lot, and it's a little bit all over the place.

Copyright basics

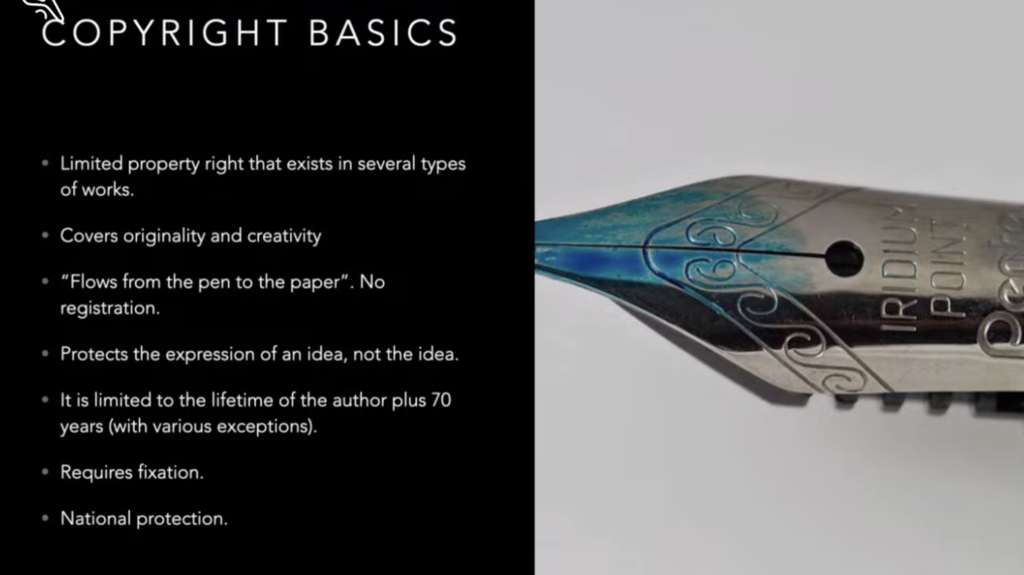

Besides being national, here are some basics of copyright:

- It's a limited property right that exists in several types of works.

- It covers originality and creativity.

This means that your work has to be original or creative. There are different standards for this. Generally, in Europe, the work has to be an intellectual creation that reflects the personality of the author, but also reflects free and independent choices. While in the US you have to have a modicum of creativity for your work to be protected, et cetera. The requirements of what is copyrightable depend on the country.

- It “flows from the pen to the paper”.

You don't need to register to get copyright, with one exception, which is the United States. In the US, you need registration to enforce your rights.

- Protects the expression of the idea, not the idea itself.

It's limited to the lifetime of the author or 70 years. This has various exceptions and changes depending on the type of work, but generally that's the standard.

- It has to be a fixed expression of an idea.

- It gives national protection.

Two types of rights

There are also two other types of rights, and this is quite important, particularly when we're thinking about your own work.

You have economic rights, which are, generally speaking, harmonized all over the world. Right to copy, rent, adapt, perform, broadcast, and issue copies of the work to the public.

In most countries, with the exception of the United States, you also have moral rights. This exists in the US, but there's a little bit of misapplication there. Moral rights are rights that you have as an author, as a person. They subsist after sale, and you have the right to have your work attributed to you. This is independent of whether or not you have sold your work. You always have the right to be attributed, and sometimes you have the right to integrity. That is the right to object to the derogatory treatment of your work.

Subject matter

Subject matter protects original artistic work. In other jurisdictions you get all other protection for things like sound recordings, films, broadcasts, typographical arrangements of published editions, etc. Generally speaking this protects literary, dramatic, musical, artistic works with other types.

The State Of Artificial Intelligence

Now I wanted to talk a little bit about the state of AI because it feels like things are speeding up.

The first predictive text [software] came out exactly 20 years ago, in 2003. That's what we have in our phones. It felt like magic. Then in 2011 we got Siri and natural language processing in 2013. Another important development was the arrival of GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) in 2014, which was the first iteration of generative network or generative AI.

Most image generators are based on something that is called a diffusion model. This first came out in 2015. Then in 2017 you got transformers which is something that allows a machine to be able to understand sentences. They don't understand it the way we do, but it allows you to talk to ChatGPT and get a response.

ChatGPT itself came out in 2018, in 2019 we got GPT2, then in 2022, we had an explosion. You have ChatGPT, MidJourney, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and all of these other tools. This year we've had incorporation to search, Adobe Firefly, GPT4, Bard, Claude, Lama, Grok, and so on.

Living in an AI world

We're living in an AI world and I know that some people don’t want this to be the case. But I think that we have to come to terms with this reality, because we're starting to see AI everywhere. There are many ways that we can handle this. There is some proposed legislation and regulations, but we have to recognize that this is happening. It's in our phones already.

Some of these tools are open source, which means that things appear to be accelerating. We're starting to see them in search engines, in Microsoft Office, and all of the Google products. Photoshop is another good example of this.

I have to stress this — people sometimes react a little bit negatively when I say this — but this is going to happen whatever we do. We can't regulate it out of existence. It is very important to recognize this fact.

I keep saying that the genie is out of the bottle and all we have to do is negotiate the three wishes, but of course everyone knows that every single story about genies is a morality play and we should be wary because the genie always wins or tries to cheat us out of their wishes. Always keep that in mind.

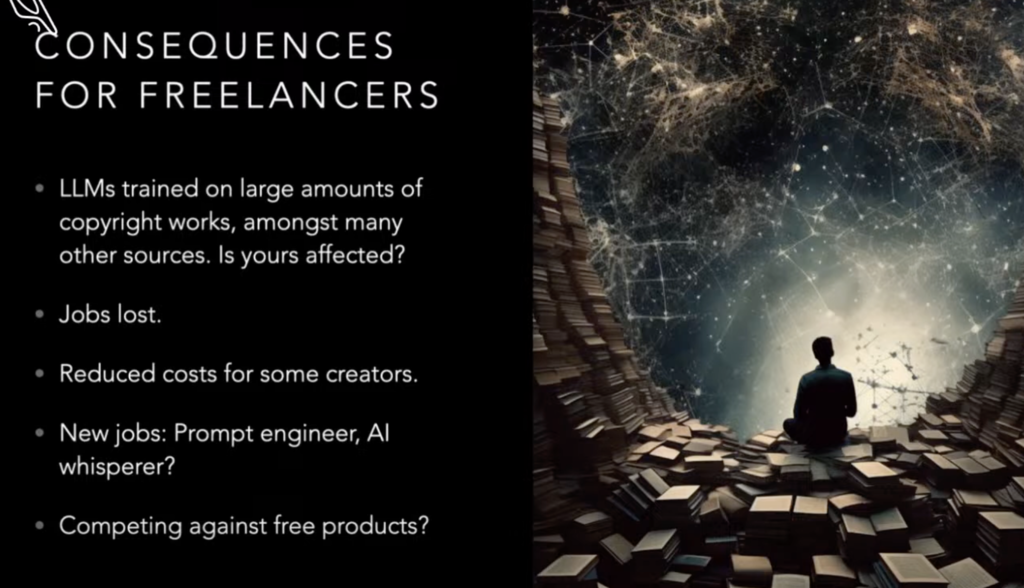

Consequences for freelancers

LLMs, large language models, but also AI image generators, etc., are trained on vast amounts of work. Some of this work is copyrighted work. It can also be trained with public domain work which is not under copyright. That usually means work from at least the early 20th century. It can also be trained with things like open source or creative commons work.

There are huge copyright implications to this.

I know some of you are translators and copy editors, and this is already having an effect. Even without generative AI, I think that a lot of people are seeing their livelihoods threatened and that the number of people that are affected is going to increase.

Using AI reduces costs for companies. If they can get an AI to do the job, they will do that without thinking twice. If my university could fire me tomorrow, they would. They would just get an AI. Everyone's job is potentially at risk.

Looking at the potential benefits — and I'm trying to look at positives as well — it could reduce your own costs in some ways. It also may mean that we're going to get new jobs like prompt engineers or AI whisperers. Potentially, humans are going to be competing with free products and I think that copyright is a piece of the puzzle.

FIND CLIENTS

Grow your business on Reedsy

Submit your application to join our curated network and connect with clients.

How to think about AI and Copyright?

There are three different questions that arise whenever we're talking about artificial intelligence and copyright in general.

The first one is whether AI generated work is protected by copyright.

The second one is whether training an AI infringes on copyright. That is what I call the input question. As I mentioned already, all these AIs, are trained on vast amounts of data. Can you support copyright infringement claims because your work has been used as training data?

The third one is what I call the output question: whenever you use an artificial intelligence to create output and this output resembles or potentially looks like another work, is that copyright infringement? Is the output itself, not the training, copyright infringement? If Hokusai or Van Gogh were alive, could they sue me for copyright infringement for creating the image that you see?

The authorship question is quite simple in many ways. We only have three options. There is the assumption that only humans can create work that is subject to copyright protection. So, only humans can create copyright. That means all of the images, all of the output, is generated work that is in the public domain where anyone can use it [free of copyright]. You can take all of my images, all of the output, you can use it yourself without infringing copyright.

Let's assume that under some systems, machines can create work subject to copyright protection. Who'd get the copyright? The user, me prompting something on Midjourney or ChatGPT, or the programmer?

We could recognize something that is called sui generis wherein intellectual property law, we have some things that are protected specifically.

⚖️ Sui generis is a Latin expression that translates to “of its own kind.” In legal contexts, sui generis denotes an independent legal classification.

In Europe, you have a database right that protects databases, for instance. So maybe we could have a specific type of right that protects work generated by a computer with shorter protection [than regular copyright].

Or we don't give them copyright, but we give them something else. Those are the only three options on the copyright.

Authorship around the world

What is happening around the world, and in the United States specifically, is that, for the most part, AI-generated work cannot be registered. And, as I mentioned, you need registration in the US in order to enforce your rights.

If you cannot register work that has been generated by an artificial intelligence, you cannot enforce your rights. This is currently being litigated in courts by the US Copyright Office and is still being discussed. The US Copyright Office is not a court of justice, their decisions are not final, but for now, in the US, this type of work does not have copyright protection.

In the UK and other countries like Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, and India, there is a provision that allows the author of work that has been generated by a computer to be the person who made it possible for the work to be created. If you generate an image with something like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion or ChatGPT, you could have copyright, though you still have to fulfill some of the other requirements, and it’s a limited type of right.

This hasn't been tested in court, so we don't know if this is going to stand up in court in Europe. In general, you have to prove that the work is a result of intellectual creation and this intellectual creation has to reflect the personality of the author while also being the result of free and creative choices.

What does that mean? If I type in ChatGPT “Please write a long poem about cats,” ChatGPT gives me a poem. Do I have copyright? No, not in most parts of the European Union. The input itself and the output is not enough to signify intellectual creation.

However, let's say you have a very complicated prompt which results in lots of output in Midjourney. The output is good, and you select one, start working on that, and keep working. In Europe, that could potentially be enough to prove intellectual creation. But we don't have case law. Ukraine is the first country in the world that has passed a sui generis. I think it's 15 to 20 years, if I remember correctly. This means if you're in Ukraine, you get some right for artificial intelligence work.

This is a really important question, because it goes back to the reasons for why we have copyright.

Do we have copyright to protect investment, to protect authors? We want to protect authors from cheap competition. Do we want to have a copyright police conducting human purity tests? I think this could potentially be problematic, again, because in most countries registration is not required. You don't need to prove to anyone that the work is yours. Which opens very interesting questions and accusations, with people saying “oh, this looks like artificial intelligence.”

The input question

For the most part, I've heard that people feel that [AI generated work] should be in the public domain. I think that there is a practical case to be made for a shorter, sui generis type of right.

You have four phases [when training AI]: collection, preparation, training, building the application. There's always the potential of having a copy of a work in the training, but usually the trained model itself does not contain an actual copy of the work. Usually the potential infringement will take place either in the collection or the preparation phase.

The trained model does not contain copies. It's not a collage machine. The model contains mathematics, statistics, etc. and it's not a publication. The one right that is being infringed is the copying. There are no other exclusive rights involved. If your text is strained, you potentially have a copyright claim.

The output question

The output question is quite simple. You ask an artificial intelligence to “produce something that looks exactly like this photo.” You may recognize the Afghan girl, it's a very famous photograph. Are any of the resulting outputs going to be infringing copyright?

In some instances yes, but it's not a collage. What the machine is doing is sort of remembering things. This could potentially have an effect in some cases that are currently ongoing. Is it a derivative or an adaptation? This is another very obscure copyright discussion, but we already have a few decisions that are going in this way.

Exceptions and limitations

There are a few exceptions and limitations that exist in this area. These are being entirely handled in the courts right now. We don't know if any of these apply.

In the United States you have fair use. It only exists in the US and most of the cases are being litigated in the US, so this is going to rest on whether or not the training in the input phase is considered to be fair use.

We have a few exceptions for dealing with text data mining in the European Union with lots of caveats and provisions. In the UK, we have Fair Dealing for Text and Data Mining for scientific research. We have a broad exception in Japan and there are other exceptions, like temporary copying and something that's called transformative use in the US, or pastiche in Europe. You can create a work that resembles another work sometimes if you transform it enough.

The AI wars

There's lots of case law in this area. There are the lawsuits of Anderson, Silverman, and Tremblay against GitHub, OpenAI, and Metastability. Everyone is getting sued.

We're going to have years of litigation and this is probably going to shape the law as we know it. This is the only game in town when it comes to copyright. You're either doing artificial intelligence or you're probably wasting your time. All these lawsuits contain lots of very interesting legal questions about using and infringing copyright. Some cases have argued that every single output from an AI tool is a derivative of all the work and input it has been trained on. Judges have already said this doesn't make a lot of sense. Everything is going to rest on the very simple question, I think, of fair dealing.

Protecting your rights

Let's say your work is in the training data. What can you do? Can you stop yourself from being in the training data in the future? There are a few tools that you can start using. Kudurru AI actively blocks AI scrapers from your website, for instance.They also created a tool called ‘Have I Been Trained’. I haven't tried it myself, but I've heard that it works quite well. It pretty much tells the scrapers not to come here. There are emerging technical standards that you can add to your work that are going to be recognized by the training scrapers to leave your work alone.

As I mentioned, there is no copyright registration [in most counties], so if you want to enforce your copyright, you only need to register it in the United States. You can register if you're a foreign national, but that doesn't have any evidentiary proof in your own country. And even registering with the US The Copyright Office is not evidence of ownership, it's just evidence that you're claiming to be the owner. Some people like doing it, but personally I don't see the point because your national court may not even take this as evidence.

There are some private registrars out there. There were even some people that were suggesting blockchain registrars which never really took off. You can also offer witness records as evidence that you are the author, like time-stamped photographs. Self-addressed sealed envelopes is another popular form.

Increasingly, I notice that my students are asking “Who cares about copyright?” Copyright is no longer important. There are generations of creators (like influencers) that are working entirely in a copyright free environment, and their income does not rely on the traditional copyright marketplaces that we know. Platforms are now enforcers because they're liable if they don't remove things. You can use the platform as your own enforcer. Courts are timely and expensive, so just send a DMCA notice and most platforms will take out your work.

In conclusion, sometimes we think about artificial intelligence very negatively. I am agnostic and I've been using the tools myself. I'm not a creator, I'm just an academic and a blogger. I don't want to preach or tell anyone what to do, because sometimes just being recognized is enough for me. But of course, that is not the case for most people. There are technical tools that you can use, if you want to opt out and there are potential opportunities for people who embrace the technology.

One thing is true: for the next four or five years, we're going to get lots of lawsuits, lots of litigation, and whatever happens is going to shape things to come. Now, we don't know the shape yet. If anyone tells you that they do, they're lying.

Q&A Session

I've worked on picture books published with AI generated images. Should authors acknowledge this somewhere in the book?

Andrés: There is the legal answer and the ethical answer. The legal answer is not yet. At the moment, you don't need to comply with or disclose whether your work has been created with artificial intelligence.

Now, I left this out on purpose, because it's ongoing, but in the EU and in the UK, there are proposed regulations that state that if you use artificial intelligence at some point, you will have to disclose it. But this is still under discussion.

Ethically, I think you should. I'm always very open whenever I use AI for presentations or anything. But, again, it's not a legal requirement.

However, if you are planning to register your work in the United States, you do have to state if your work has been generated with AI. There is not going to be a copyright police, as I mentioned, but they may deny registration. Lying to the US Copyright Office is a criminal offense. I don't think that they're going to prosecute you, but if you live in the United States and you don't want to go to jail, please don't lie to the US Copyright Office.

What are the copyright implications when creating content using AI assistants to enhance or supplement original work versus wholly generated content based on author's prompts or concepts?

Andrés: That is a fantastic question. We don't know yet. I'm a lawyer and I always answer with “it depends.” It depends on your jurisdiction.

In the US, the US Copyright Office is leaning very hard against AI works. We don't know if this is going to remain; we'll have to wait for some cases to be settled, but, at the moment, let's say you're using something like Photoshop, which now has built-in AI capabilities, I don't think that you have to comply with that requirement because that would be more assisted. You are creating the work yourself and the AI is assisting you.

Of course, this is not legal advice. I would recommend you to check with your local jurisdiction to see what's happening, but for the most part, I think if it's assisted, you don't have to comply.

I think that in Europe, if the work is created with assistance, let's say with ChatGPT, it might be fine.

I'm not a native English speaker, for instance, so I sometimes get ChatGPT to check my English. This is assisted, and I think that's perfectly fine. I still have the full copyright because I wrote the sentences.

Some of these questions are completely new and we'll have to get case law to pick at the boundaries of some of these questions. It may depend entirely on how much you've done. At least in Europe, and this includes the UK, we have case law that says that if you do a selection of photographs or text, that is enough to give you copyright.

That is one of the reasons why most photography actually allows you to have copyright. Just the choice of angle, choice of situation, even being in the right place at the right time can confer you with copyright protection.

It may depend on how much assistance is offered . I hope that answers it.

If an author creates a story using an AI text generator, then I, an editor, edit and rewrite significant portions of it, has it become an original work? Who's the owner of that work?

Andrés: I think that if we recognize — again, this is a big if — that this work may have copyright to begin with, I think that joint authorship may be in line. Joint authorship is whenever you cannot identify specifically who the author is.

Martin: This is like probably the biggest issue we might face on our marketplace in terms of AI.

Because there is such a market for new content on Amazon, there is the danger that people generate a first draft manuscript for nothing using AI, send it to our editors to basically clean it up, and make it feel like a real book. At that point, there are editors who want to have a certain guarantee to know whether it is AI and whether they are being co-opted into authoring a book without knowing it.

I'm not sure if this may also come down to contract. A lot of these things are already starting to be decided and being written into contracts.

I think that the writer's strike in the US was a big indication that people are going to start writing clauses on artificial intelligence into their contracts.

Will Reedsy be adding to the standard contract that manuscripts must not be generated by AI?

Martin: At this point, I cannot say. I guess it is a matter of the distinction between assisted and fully generated. How can we police it? If one of our freelancers suspects a manuscript was generated by AI, we could probably run it through an AI detector, but it wouldn’t give enough legal grounds for us to reject their work.

Andrés: I would add to that that AI detectors are extremely bad. Do not make any important decision based on AI detectors. They have too many false positives, too many false negatives. If you suspect that someone used AI, try to use some other evidence. Sometimes it's very evident, but we are not using it for anything that is important ourselves.

If a publisher asks for AI acknowledgement when considering your work, is that binding in any way? Can you lie to a publisher?

Andrés: Again, ethical and legal. Legally, I don't know. If you're lying, there could be legal consequences if they write it into your contract. You signed it, so you're bound by it. If it's not, I guess you can lie, but ethically I wouldn't recommend it. It’s not good to lie in those circumstances.

Again, it's my legal opinion, but please consult your lawyers. These are very general statements.

FREE RESOURCE

The Full-Time Freelancer's Checklist

Get our guide to financial and logistical planning. Then, claim your independence.

For more discussion on Artificial Intelligence in Publishing check out this webinar, or read this blog post for tips on getting more freelance clients, or notifications about events like this, subscribe to our Freelancer newsletter or follow us on LinkedIn.

Reviewed by Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

As the editor of Reedsy’s freelancer blog and a writer on the Reedsy team, Linnea has her hand in a bit of everything, from writing about writing, publishing, and self-publishing, to curating expert content for freelancing professionals. Working together with some of the top talent in the industry, she organizes insightful webinars, and develops resources to make publishing more accessible to writers and (aspiring) publishing professionals alike. When she’s not reading, she can be found dribbling on the football pitch, dabbling in foreign languages, or exploring the local cuisine of whatever country she happens to be in at the time.