Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

Dan Harmon Story Circle: The 8-Step Storytelling Shortcut

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →The Dan Harmon Story Circle, also known as “The Embryo”, is an approach to plotting developed by TV writer Dan Harmon. It follows a protagonist through eight stages, beginning with the character being in their comfort zone, then venturing out into the unknown to seek something they want. The character achieves their desire, but at a great cost, and ultimately returns transformed by what they’ve experienced.

This narrative framework is applicable to a wide range of genres and forms, and is a great way to structure any story that focuses on character development. This post contains a breakdown of the individual steps, gives examples of the Story Circle in action, and explains why it’s such an invaluable template for writers.

What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

This particular story structure is adapted from the monomyth, also known as The Hero’s Journey — which itself derives from the work of academic Joseph Campbell. The Story Circle lays out a kind of narrative arc that's commonly used by myths from all over the world and emphasises how almost all forms of storytelling have a cyclical nature. In broad strokes, they always involve:

- Characters venturing out to get what they need, and

- Returning, having changed.

Q: Can I break traditional story structure rules and still write a good book?

Suggested answer

The quick answer to this is yes!

The longer answer is that, in order to break the rules of traditional story structure, you must first understand them. Authors who are successful at going completely outside of the 'norm' in storytelling and writing really know their stuff. They understand why the 'rules' are in place, and then they work hard to go against them in a meaningful, intentional, and acceptable way. If you look at experimental literary fiction, for example, you'll see a lot fewer examples than, say, the typical commercial fiction novel. In commercial fiction, there are certain expectations in terms of style, voice, tropes, structure, etc. Readers go to these types of novels to have their reading desires and expectations fulfilled. But that doesn't mean you can't surprise them every now and again.

The great thing about writing fiction is that you can do whatever you want--the sky is the limit. Structure, style, etc. can be played around with, but it must be exquisitely executed. And to achieve that, you must first know the rules like the back of your hand and master them.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking the traditional story structure is best done after you have a few books under your belt and are a seasoned author, especially if you are seeking a traditional publisher. There is enough risk for publishers to take a chance on a new author without the added risk of trying to push something that is out of the box. There are many people in the publishing chain of approval, and trying to sell the idea to the bulk of a publishing staff can be challenging if the author has no track record of sales to speak of.

When starting out, it really is a good idea to "play by the rules" if and when possible. That doesn't mean your book will not be "good" if you break the rules, but it's risky. Because the reality is that not all "good" books get book deals. This business is very subjective, and publishers run for-profit businesses, and they want and expect to make money on their books. Unfortunately, every decision regarding books that get chosen for publication is not based on artistic merit alone.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The Story Circle functions similarly — so, you may ask, why not just use the original? In short, Campbell’s system is more complex (11-steps), and alludes to a particular type of story, namely high fantasy (think knights, wizards, potions, and swords in stones). What Harmon did was streamline this process to just eight steps, and broaden them out to be less genre specific. The benefit of Harmon’s version over Vogler’s is that it focuses more specifically on character and is much easier to apply to a wider range of stories.

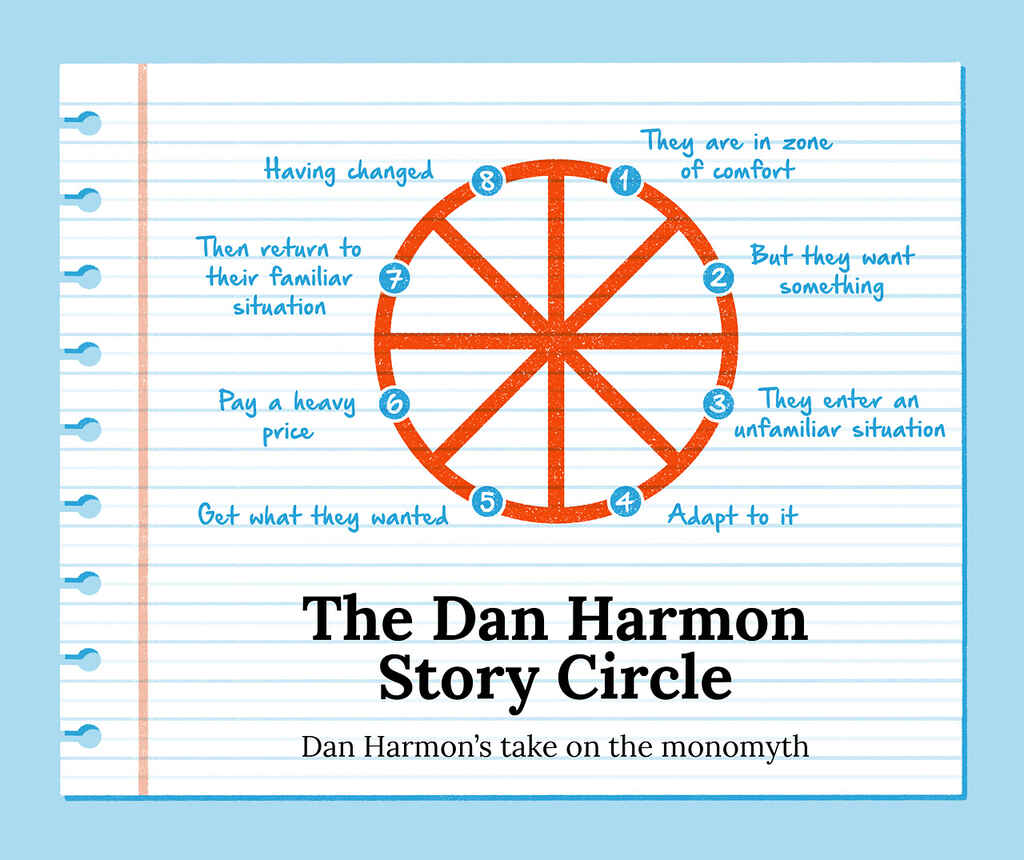

The steps are comprised of basic human motivations, actions, and consequences, which he lays out in a circle:

You might be asking why Harmon doesn’t just lay this structure out in a flat line. When asked about this, he points to the rhythms of biology, psychology, and culture as his inspiration: how we all move cyclically through phases of life and death, conscious and unconscious, order and chaos.

The fascinating thing he points out is that cycles like these are, in part, what have allowed humans to evolve.

“Behind (and beneath) your culture creating forebrain, there is an older, simpler monkey brain with a lot less to say and a much louder voice. One of the few things it's telling you, over and over again, is that you need to go search, find, take and return with change. Why? Because that is how the human animal has kept from going extinct, it's how human societies keep from collapsing and how you keep from walking into McDonald's with a machine gun.”

“We need [to] search — We need [to] get fire, we need [to find a] good woman, we need [to] land [on the] moon — but most importantly, we need RETURN and we need CHANGE, because we are a community, and if our heroes just climbed beanstalks and never came down, we wouldn't have survived our first ice age.”

What Harmon's getting at is that stories are a basic, universal part of human culture because of their millennia-long history as both a teaching and a learning tool. This idea of questing, changing, and returning is not a hack concept concocted by lazy writers, but an ingrained part of our collective psyche. That’s why stories from one culture are able to resonate with people across the world.

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In Harmon’s philosophy, when a book, film, show, or song doesn’t meet the criteria above, it’s not necessarily bad writing: it’s simply not a story.

The 8 steps of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Now that we’ve got the background, it’s time to get into the meat: what are the steps of the Story Circle, and what do they entail.

Here are the Story Circle’s 8 steps:

- A character is in a zone of comfort. Everyday life is mundane and unchallenging.

- But they want something. The protagonist’s desire compels them to take action.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation. The character crosses the threshold to pursue what they want.

- Adapt to it. They acquire skills and learn how to survive in this new world.

- Get what they wanted. The character achieves their goal, but at a cost.

- Pay a heavy price for it. New and unexpected losses follow the victory.

- Then return to their familiar situation. The character goes back to where they started.

- Having changed. The story’s resolution; the lessons they’ve learned stay with them, and the character has grown.

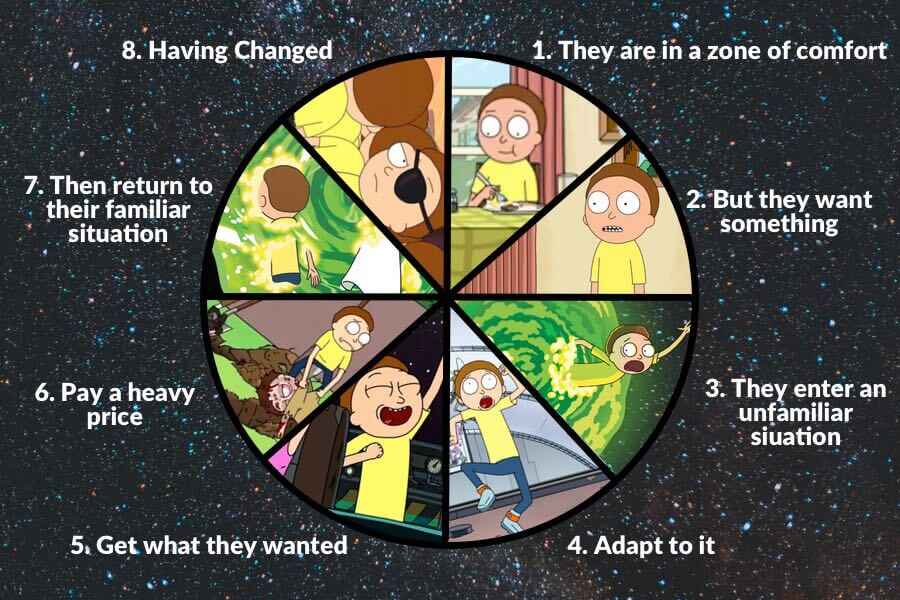

There's perhaps no better example of this system in action than the sci-fi comedy series, Rick and Morty, which Harmon co-created. Known for its fast-paced, pop-culture-inflected humor, affection for science fiction tropes, the show has also been praised for its dense storytelling, often fitting in a feature film’s worth of plot within a modest 21-minute runtime.

In the video below, Harmon applies the story circle to an episode of Rick and Morty entitled “Mortynight Run.” For enough context to understand the clip, here’s some background info:

Rick is a mad, drunk, egomaniacal scientist who has invented a portal gun that allows him to have debauched adventures across time and space. He almost always drags his sensitive, anxious grandson Morty along for the ride. In this episode, they also bring along Morty’s father, Jerry, for whom Rick only has disdain.

Let's take another look at how the episode’s “A” story — which centers on Morty's journey — fits into the story circle.

1. A character is in a zone of comfort

The first beat of the story sees Rick and Morty on what seems like just another one of their adventures, flying through space with Jerry in tow. Things take a turn when Rick takes a call to organize a shady deal, and unceremoniously dumps Jeff from their spaceship.

It becomes apparent that Rick is carrying out an arms deal, selling weapons to an assassin to pay for an afternoon at the arcade — much to Morty’s dismay.

Q: What techniques can authors use to hook readers from the first page?

Suggested answer

Start with your main character doing something somewhere and start in the middle of the action. If there is a hurricane coming, have them board up the windows of their home. If they are dreading an upcoming test at school, have them look over their last test grades and worry that this next test won't be any different.

You want to avoid "talking heads." This is what publishers think when there is dialogue going on between characters, and because there is no sense of "place" or "setting", the story comes off as characters "talking in space." This is why you want the characters to be somewhere and do something in every new scene you draft, not just the opening.

Readers like to visualize the action in a book, even if the "action" is inward. So start off with a visual picture of your main character doing something, and this should hook readers.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I recall reading a memoir of a famous tennis player and he started it by plunging the reader into his experience of facing a relentless machine shooting balls across the net to him -- all the fatigue and pressure of trying to become a pro was encapsulated in the scene. Much more interesting than starting it with when and where he was born etc.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

2. But they want something

As Harmon points out, “This is an ethical quandary for Morty.” The boy is put in a situation of guilt that compels him to “go across a threshold and search for a way to undo the ethical damage that he perceives Rick as doing.” Putting things right is Morty’s “want”, which takes us to the next stage.

3. They enter an unfamiliar situation

Even though he rarely defies his grandfather’s instructions, Morty takes Rick’s car keys and chases after the assassin, accidentally killing him in the process. He’s now trapped in an Intergalactic Federation outpost.

Q: What is the biggest mistake writers make in their opening chapters?

Suggested answer

The biggest mistakes I see in the opening chapters of new authors are:

- Spending too much time on backstory that is not needed in the present moment or in the opening situation the book starts with. Any backstory information that is crucial to the story should be woven into the narrative as the story goes along or introduced after the initial inciting incident. The reader needs to know enough about the character to care about what happens to them and to begin rooting for them, but they don't need to know their entire life's story or all of the characters that occupy their world.

- Not providing enough information to give the story a sense of place, especially in stories that do not take place in the present day. In historical, sci-fi, and fantasy, there needs to be some time spent in world-building by placing descriptive sentences here and there in the opening. For instance, stating that someone is traveling in a carriage denotes a historical novel. Traveling at light speed in a spaceship evokes images of sci-fi and perhaps another planet or world. So be sure to place your characters in this new world right away.

- Not starting to move quickly enough into the inciting incident or the catalyst of the story, and spending too much time on non-consequential details like gardening, eating, riding a bike, brushing teeth, etc. There needs to be some type of action and some sort of trouble within the first 12,000 - 13,000 words. This is a good benchmark to shoot for as far as having your inciting incident occur by this point in the story.

You may have to try a few ways and experiment with different points in time as far as where your book needs to start.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Your first chapter has a lot of work to do. It needs to engage readers straight away, and by readers I mean everyone from a literary agent's assistant to a commissioning editor, a book marketer, or someone in a bookshop idly picking it up. That means something has to ignite in those first few thousand words, whether a plot, a question or a voice.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

4. Adapt to it

Morty discovers an alien gas entity named ‘Fart’ — who was the assassin’s target. Going against Rick’s instructions once more (and making what he believes to be the ethical choice), Morty liberates Fart from space jail and they make their escape.

5. Get what they wanted

Morty has achieved his goal: he’s saved a life, and stopped a prolific assassin — and can now rest assured that he’s done the right thing.

6. Pay a heavy price for it

“In the second half of the story, we start finding out that the act of saving that life is going to cost a lot of other people their lives,” Harmon explains. Bounty hunters and law enforcement are seeking the group, and Fart slaughters many space cops and innocent bystanders while Rick and Morty make their escape.

Q: What is the 'saggy middle' in storytelling, and how do I fix it?

Suggested answer

A 'saggy middle' occurs when a story loses momentum, tension, and trajectory right around the midpoint of the story. A story can lose it's steam (and with it, a reader's interest) when character arcs stall, plots become muddled and messy, and subplots abound with no sense of direction. Stories can also sag if they fill pages with descriptive information that does little to engage the characters or further the story arc.

But never fear! This is a very fixable problem. First, think about the ideas at the heart of your story. What story do you want to tell? What lies at its core?

With that in mind, review the midsection of your story with an eye to the issues described above. Once you identify your problem areas, you can set about rewriting with a goal of increasing the tension by increasing the stakes for your characters, adding new conflicts/problems for characters to explore, cutting excess descriptions and sections that over-explain character motivations/backgrounds/actions, and tightening sections that do little to further the core plot that drives the story.

Erin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I tend to see saggy middles show up when authors are adhereing to a strick timeline of events, rather than sharing scenes that pull the plot forward. For example, I edit a lot of middle grade fiction and a saggy middle might include multiple chapters that open with the protagonist waking up and close with the protagonist going to bed. Or going to school, then getting home after. Readers don't need the day-by-day minutia to get from one scene to the next.

Instead, focus on what will pull your plot forward, and think of your middle as scenes rather than a timeline that gets you from point A to point B.

I usually suggest that authors step away from the manuscript and instead write scenes, even if out of order, that they need for their story to make sense. When finished, they can line them up in order, and then fill in the blanks for a much faster-paced and cohesive middle. Even if you don't have a saggy middle, this is an effective practice for planning and plotting purposes.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The 'saggy middle' of a story is the part of the story where the inciting incident - or the problem in the story - has already happened, but the ending, or climax and resolution, is nowhere in sight. It really does fall in the middle of the story.

There are several ways to handle this issue:

*Use a subplot with the main character or a secondary character that will still need its own resolution and will bring in another layer of trouble for your character[s]. In The Wizard of Oz, each of Dorothy's three friends suddenly has their own problems. The scarecrow loses his stuffing, for instance, so the storyline shifts for a bit from Dorothy's desire to get back to Kansas - her hero's journey and the through line of the book - and takes a slight turn to focus on the scarecrow and friends before turning back to Dorothy's main plot line again of getting home.

*Raise the stakes - create even more trouble for your character and/or make the result[s] of the trouble even more dire. In the book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, first, Mrs. Morris the cat is sent to the hospital, then humans that are Harry's friends, then finally, Ginny is in trouble, who will end up being Harry's love interest. So the stakes and problems keep building all the way through the book until the final climactic scene.

*Use what is called a 'midpoint reversal': This is where the character changes his mind about the issue and is not opposed to it any longer. In the movie "Tootsie", at first, Michael does not want to pretend to be a woman to get work, but by the middle, he loves the idea of pretending to be a woman and wants to take things even further, which causes friction between Michael and his agent. So more trouble occurs because of this mindset reversal, which then leads the book to its satisfying conclusion.

You don't have to use all of these techniques, but try one out in the middle of your book, and see which one works best for your own story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

7. Then return to their familiar situation

After the escape, the gang returns to a place resembling ‘normal life’, a phase Harmon refers to as “crossing the threshold” (here metaphorical, rather than a literal return home). At this point, Morty realizes that Fart is a truly malevolent creature and means to return with his people to destroy all carbon-based life.

Note: On the Circle diagram, Step 7 (the return) is directly opposite to Step 3, where Morty first crossed the threshold into the unfamiliar situation. Balance and harmony are a big part of Harmon's approach to storytelling.

8. Having changed

“So Morty makes the decision to change into someone who kills.” Realizing that his belief that all lives must be saved is not an absolute truth — some are simply malevolent — he terminates Fart, thereby saving the universe and becoming someone different from the person he started as. As Harmon points out, this is not a show for kids: not all protagonists need to learn universally positive messages for a story to ring true.

Harmon has laid out his process for using the story circle in a fascinating set of posts (warning: contains swears) where he also talks about the nature of storytelling, answering questions like…

Why use the Story Circle?

According to Harmon, the beauty of the Story Circle is that it can be applied to any type of story — and, conversely, be used to build any type of story, too.

“Start thinking of as many of your favorite movies as you can, and see if they apply to this pattern. Now think of your favorite party anecdotes, your most vivid dreams, fairy tales, and listen to a popular song (the music, not necessarily the lyrics).”

So let’s put that theory to the test. Let’s pick an example that’s far removed from Harmon’s own work see if it applies: Dickens’s Great Expectations.

- Zone of Comfort: Pip, a young orphan, lives a modest life on the moors.

- But they want something: He becomes obsessed with Estella, a wealthy girl of his age.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation: A mysterious benefactor plucks Pip from obscurity and throws him — a fish out of water — into London society.

- Adapt to it: He learns to live the high life and spends his money frivolously

- Get what they wanted: Pip is finally a gentleman, which he believes will entitle him/make him worthy of Estella.

- Pay a heavy price for it: Pip discovers that his money came from a convict, he drowns in debt, he regrets alienating his Uncle, he realizes that his pursuit of Estella is futile.

- Then return to their familiar situation: Pip makes peace with his Uncle Joe (who nurses him back to health). Pip disappears to Egypt for years, and once again returns home…

- Changed: Back once again where the story started, a now-humbled Pip reunites with Estella who, due to some plot, is ready to open her heart to him.

Although Great Expectation was a serial, written week-by-week, Dickens must have consciously or unconsciously been aware of this cycle, or something like it. He sent his characters on a journey towards something they wanted — only for them to pay the price and return home, changed.

Q: What techniques can authors use to create a redemption arc that feels emotionally authentic and believable to readers?

Suggested answer

Redemption arcs are layered. There’s the external of redeeming one’s self to others. And the internal of redeeming yourself in your own eyes. Both are emotion packed. I think the characcter’s understanding of why redemption is needed, how to get there, why it matters, and what it means for the future should be examined and reexamined by themselves and those around them to whom redemption matters. That builds emotional stakes and tension. And it will make the redemption success or failure matter more not just to characters but to readers.

Also, don’t go cliche. Redemption arcs are great storylines but they are also common storylines. So make sure that your beats take unique twists and turns that surprise us. Character actions, especially the person who needs redemption, are core to this. They should be clear what they want and how they intend to achieve it in some way and fail multiple times along the way, forcing them to learn lessons and change course. All of those failures can be surprising and frustrating as long as we care what happens, especially if we care about the characters. The trick is to make sure even if using old trope points that you give them new energy and reframe them in new and interesting ways.

In the end, what is believable is that the character is imperfect but becomes a better person on the path to redemption. It’s believable that some other characters have given up on the hero and doubt redemption can occur, while others remain optimistic. It’s believable that the character has to leave behind selfish, self-serving tendencies to become redeemed. And it is believable that when it happens, no one takes greater satisfaction in it than the character themselves because they learned so much about life and caring and giving, etc. on the journey to get there.

I love a good redemption story. That’s how I’d approach it. I hope this helps.

Best,

Bryan

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I'd say the main thing here is to stay true to the character. The redemption has to feel authentic based on how the character's been presented thus far in the book/story. Keep in mind the character's past actions and reactions as a whole. Because in the end, if the redemption feels like it's been shoehorned in or has come out of left field, the reader will feel that. However they redeem themselves, it has to feel like something that specific character would do—not just any character who's gone through the things they've gone through, but that character in particular. As for impact, the more three-dimensional the character is, the stronger the impact will be when their redemption comes about, so making sure they have a well-rounded, more-than-surface-level personality is absolutely key.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

As with any sensible advice about structure, the takeaway here is not that you must slavishly adhere to a set formula or risk ruining your story. This story circle, along with other popular story structures, are simply tools based on observations of stories that have managed to resonate with readers over the centuries. They can also be a great tool to know what should come next, and to pace yourself within your story — if you’re halfway through and still in the comfort zone, you know you need to make some changes.

There are, of course, plenty of other options for story structure, which you can learn about by reading the rest of this guide — or trying the quiz below!

✍️

Which story structure is right for you?

Take this quiz and we'll match your story to a structure in minutes!

Just know this: if you find yourself at an impasse with any story you’re writing — you could do a lot worse than crack out the story wheel, identify where you are, and see what comes next in the cycle.

3 responses

2deuces says:

25/07/2018 – 19:48

This is great. One difficulty about using the Hero's Journey and other Plot Structures is that the main character needs to end up in a different place than at the beginning. That is fine for a movie or a stand-alone book, book but what about episodic series such as Perry Mason, Poirot, or just about any TV series. The Story Circle solves this problem by bringing the MC (actually the entire cast) back to the beginning waiting for the next case, next mission, next customer to enter the bar etc. Even if the series has a long arc (Breaking Bad) over time we see Walter slowly evolving due to the impact of each episode.

↪️ Martin Pitt replied:

26/07/2018 – 20:33

The location does not need to differ, the change here explained was to the character themselves. After all with the given example, Morty usually always ends up back home. Whether they realised some truth, became more humble, or worse; On that note: If the character is worse off that could be fixed in a future story or you could have a really great villain on your hands to play with! Regardless, change could be anything I think or to someone else.

↪️ 2deuces replied:

27/07/2018 – 17:14

Sorry I didn't mean a different location but a different psychological place. Scrooge woke up in his bedroom but he was a different person on his return.