Last updated on Oct 14, 2025

A Century of Fantasy: How the Genre's Changed Since the 1920s

Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

View profile →The English word, "fantasy," sprang from Old French's phantasie, or "vision, imagination." But you wouldn't be entirely remiss if you'd thought that it came from the word "fantastic." When you consider all the fantastic things in our world and our imaginations, it's no wonder there are so many different subgenres in fantasy — and dedicated readers of each subgenre.

In our previous piece in this series on writing fantasy, our editors gave tips on writing compelling fantasy fiction. In this post, we conduct a brief examination of the evolution of the genre and its subgenres. Because we've only got so much space, we're going to concentrate on the Anglophone side of things — though fantasy is a worldwide phenomenon that's got roots in Indian myth, dating back to 1500 BC. And yet, up until the 1940s, "fantasy" wasn't even a universal term for the genre yet! ("Fairy tale" was preferred.)

How did we get from there to fantasy's current, steadfast position in mainstream English literature?

The Two Giants of Fantasy

Enter two names that you might’ve come across before: C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

The two fathers of fantasy met in 1926 on the campus of Oxford University, where they were both on the faculty together. (Lewis was a part of the Literature faction of the English faculty. Tolkien, unsurprisingly, was more of a Linguistics person.)

Because they were burgeoning friends, they swapped works and workshopped each other’s ideas in a writing group called the Inklings. Little did the group realize that they would be founding modern fantasy. Critic Philip Zaleskis noted: “Without the Inklings, there would be no Dungeons & Dragons (and the whole universe of online fantasy role-playing it produced), no Harry Potter, no Philip Pullman (in the role as the anti-Lewis).”

Of course, Lewis was the more prolific of the two. Starting with The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, Lewis published seven popular books in seven years. His imaginary Narnia was a whimsical universe. It stuck to the perception of the time that fantasy belonged in children’s books (and to be fair, children's fantasy is pretty awesome). But it was Lewis’ Narnia that began popularizing fantasy among the broad public up until the 1950s, which is when Tolkien published Lord of the Rings.

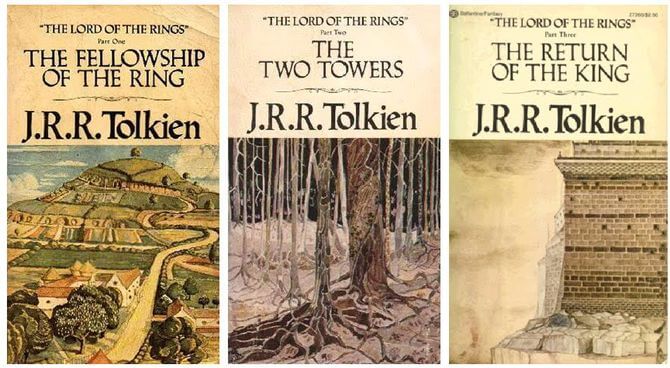

Today, it’s practically impossible to overstate Tolkien’s impact on the genre. There’s no author who towers over one genre as Tolkien does — up to the point where you need to talk about the genre in pre-Tolkien and post-Tolkien terms. In what ways did Tolkien contribute to the genre?

Well, pretty much of all of them.

- Silmarillion cemented the trope of the creation myth.

- The Hobbit, with its talking animals and simplistic themes, epitomized children’s fantasy and fairy tales.

- Lord of the Rings towers over all of fantasy. It established (among others) these tropes in High Fantasy: the quest, the band of good guys, the wise mentor, good against evil, the Dark Lord, and the trilogy.

Above all, Tolkien invented tongues and an entire self-contained mythology, imbuing it with life. The constant whimsy that carried Alice in Wonderland or L. Frank Baum’s Oz books wasn't present in Lord of the Rings. That made Middle Earth seem as though it was a universe that actually existed before Earth.

Good news! Here are 12 of the best epic fantasies to tide you over until the next Game of Thrones installment comes out.

Katherine Kerr, a bestselling fantasy author, put it best:

The thing is that most people who read Tolkien only once tend to forget who was who. What they do remember is Middle Earth itself. It’s got all the properties – the soul and the presence, the depth, the personal quirks, and the feeling of an existence outside the books – that Tolkien’s characters so often miss out on. Those of us who read the books many times come away again in awe of this achievement. Along the songlines of Middle Earth, Europe’s dreamtime comes alive.

Kerr also argued that fantasy authors needed to move on from the Master, in part because of one small flaw: Tolkien’s characters could too often be boiled down to archetypes in Capital Letters (The Dispossessed King, The Evil Lord, The Mighty Wizard). But Tolkien put down the stones and built up the walls for the genre. His genius was a bit of a double-edged sword: paving a way for the future of fantasy, but casting a shadow as big as Mount Doom’s, to this day.

How did authors that came after Tolkien emerge from it?

The divergence of fantasy subgenres

So one author just re-defined the whole genre. What do you do now?

Well, some fantasy writers seemed to draw their inspiration directly from Lord of the Rings. (See: Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara in 1977.) This continued Tolkien’s brand of sword-swinging and quest-intense fantasy that furthered epic fantasy.

But other authors began seeking to subvert the tropes that Lord of the Rings so intimidatingly set in place in fantasy. One such writer said:

“I admire Tolkien greatly. But the trope that Tolkien established — the idea of the Dark Lord and Evil Minions — in the hands of lesser writers over the years and decades has not served the genre well. It’s been beaten to death. The battle of good and evil is a great subject for any book and certainly for a fantasy book, but I think ultimately the battle between good and evil is weighed within the individual human heart and not necessarily between an army of people dressed in white and an army of people dressed in black. When I look at the world, I see that most real breathing human beings are grey.”

This writer's name? George R.R. Martin. He went on to write a small something called A Song of Ice and Fire, making good on his word. Out went the talking elves! Away with the good guys versus one Dark Lord and Evil Minions! He basically took Tolkien’s Sword and Sorcery subgenre and rendered the story gritty, the characters morally ambiguous, and the world (some might say) more “realistic.”

He wasn’t the only author who wrote with this thought in mind. Joe Abercrombie’s First Law series and Scott Lynch’s Gentleman Bastards series all produced bleaker, bloodier, and morally ambiguous scenarios — birthing the grimdark subgenre.

Then there was Ursula Le Guin. In Earthsea, she made a universe that rivaled Tolkien's for fullness and complexity while populating it with characters that were diverse and relatable. Tor's Michael Swanwick once asserted that "trying to measure Le Guin's importance to the field is like trying to figure out what salt means to the sea."

But the imaginations of our writers stretched the definition of fantasy still more. Urban and paranormal fantasy (if a troll, a wizard, and a goblin walk into a bar in New York . . . ) was the result of authors scramming out of medieval forests entirely. Instead, they put the supernatural right in our own cities. Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere wondered whether there could be a "London Below," while the popularity of Anne Rice’s 1976 Interview with the Vampire foreshadowed the coming success of a certain glittering fanged creature in the 21st century. (Spoiler alert: that's Twilight.)

What else? Historical fantasy grew in the 1970s, and there's steampunk fantasy, which crossed with science fiction to produce a new scope of imagination... the tally goes on. Currently, there are a gazillion fantasy subgenres that've splintered out. And yet fantasy was still considered a relatively niche genre up until the turn of the millennium.

So it's curious that it seems to actually be young adult and children’s fantasy that changed all of that. First, Harry Potter got everyone reading fantasy. Then the genre really sprang into popular culture when the advent of CGI took fantasy from our books to our silver screens. Suddenly, the worlds that we could only envision in our minds were right in front of our eyes.

In 2002, Peter Jackson captured the attention of both readers and non-readers with the Hollywood adaptation of Lord of the Rings. Then Game of Thrones started showing up on our televisions every week, and that, as they say, is that.

Where will fantasy go now?

We mentioned it already, but we’ll mention it again. There really is no better time to write fantasy. When you think about it, the biggest pop culture phenomena since the turn of the millennium almost all have ties to fantasy: Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Twilight. Even The Hunger Games is a dystopian fantasy, set in an entirely imagined (albeit terrifyingly bleak) world.

Looking back now, it’s easy to see the many ways that the genre’s evolved since the days of Tolkien. Consider The Hobbit, which possessed a grand total of zero women. Then take a gander at all the girls who are mainstays in the most popular fantasy books now (Hermione, Katniss).

Admittedly, it’s tough to predict the future, but at the rate that the genre’s progressing, there are two big trends that will carry us through the next couple of years:

- An ever-diversifying spectrum of characters and worlds as fantasy expands beyond its European and medieval roots. In Tor.com’s past open call for submissions, for instance, they specifically asked for novellas that were not based on European cultures — seeking, instead, worlds that “take their influences from Africa, Asia, the indigenous Americas, or any diasporic culture from one of those sources.”

- Further genre- and subgenre-blurring. Fantasy already overlaps with romance, mysteries, and thrillers — and we’ll see much more of fantasy’s influences in other genres as the spectrum of writers and readers continues to broaden.

- Fantasy traditions of other countries will impact the stories of the Anglophone world. Russia, for instance, recently pioneered the increasingly popular "LitRPG" genre, where the stories take place in worlds with video-game mechanics.

Ultimately, the future of fantasy rests on the imaginations of all the writers out there. How will you show us glimpses of another universe? People are always wanting to escape from reality. And so it's Lloyd Alexander, the author of the famous The Chronicles of Prydain series, who states the purpose of modern fantasy best: “Fantasy is barely an escape from reality. It’s a way of understanding it.”

Has this post inspired you to write fantasy of your own? Tell us about your ideas in the comments. And if you want to get an even more concrete idea of fantasy's evolution, check out this post of the 100 best fantasy series of all time.

7 responses

maryj59 says:

04/10/2017 – 20:43

I grant you, this is meant to be a history of English fantasy. But I don't see how you manage to write such a post without once mentioning Ursula Le Guin. Or Neil Gaiman, for that matter.

↪️ Joshua Muster replied:

04/10/2017 – 21:59

It seems like the purpose of this article is more to show how much fantasy changed when Lewis and Tolkien altered the course of the genre. Ursula Le Guin and Neil Gaiman absolutely were influential authors in the genre, but I believe Reedsy's point is that they were more riding the wake of the Inklings. As in, would their works even have come to be imagined and writ if not for the works of the others before them? And to argue their need to make the list based on a claim of fairness, one would need to argue for many other authors as well.

↪️ maryj59 replied:

05/10/2017 – 03:13

Since Le Guin was writing fantasy and SF in the early 1960s and late 50s, she deserves to be mentioned as one of the people who changed it. She did. To my mind, she is close to being up there with Tolkien, while many of the authors mentioned are not. Of course, tastes vary!

↪️ Joshua Muster replied:

05/10/2017 – 04:24

Excellent point haha I'm actually one of the rare people who didn't enjoy Game of Thrones (I stopped before even finishing book 2).

Joshua Muster says:

04/10/2017 – 22:00

Great summary, thanks for posting!

Guts says:

05/02/2018 – 08:07

Very interesting read! I've been obsessed with fantasy since I was a young boy and popped in the cartridge of Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time into my Nintendo 64. My first love was role-playing video games, my second was the Harry Potter books and my third was the Lord of the Rings movies. My first attempt at writing fantasy came when I was in grade six where I scribbled on line paper the first ideas I had. I can't remember the story very well but I remember It started it off with a chapter of foreshadowing- before I even knew what foreshadowing was. Later In grade seven I wrote a six page fantasy story for my English assignment which received a glaring F. Flash forward ten years and I finally found the courage to once again try my hand at creating the world inside my mind; the one that was brimming with imagination and had been accumulating like dust over time. I wrote sixty pages (approximately 35,000 words) before I read it aloud and nearly died of embarrassment. (Though to be fair, it was much better than my earlier attempt in grade six) What did I do from here? I researched. I tried to understand what made a great story and I surfed through hundreds of articles just like this one before I finally found the confidence to continue writing. I took out my trusty tablet, I scrapped my original story for everything good in it and I began to write once more. No matter how bad it got, I continued writing. After a few months I finally finished the rough draft of my first fantasy novel, a whopping 125,000 words long. Now this leads me to the present time where I haven't typed a single word into the good copy but have spent weeks and weeks slowly editing and building my glossary. I realized my own strengths and flaws as a writer but I found that I thoroughly enjoyed the experience. Sometimes I feel like I can't be a successful author because of my lack of mastery for the trade. I frequently make grammatical and spelling errors, I had no idea who Ursula Le Guin is until just now, I still have trouble remembering which is high fantasy and which is low.... and yet I still write. I still pursue. I still dream. The point of this dribble? I really have no idea.

Ben says:

10/05/2019 – 14:00

This is a really great survey, but I think it should have mentioned the enormous contribution that Robert E Howard made to the genre, completely independently from Tolkien. Tolkien was shown some of REH’s stories later on, and “rather liked” the Conan stories.